The John Nesbitt Story:

The First

Afro-Native American

MAC-V Recondo Advisor

— Part One

By John Nesbitt

Viet Nam: An account of the experiences of Sgt. John E. Nesbitt, 16-844-233,

Detachment B-52 Delta Project

From September 18 through December 1966 and

from December 1967 through May 1968

at the MAC-V RECONDO School,

RECONDO STUDENT # 114,

RECONDO ADVISOR #135

From June through October 1968 at

Detachment A-401 DON PHUC, Mekong Delta,

CIDG Company 43, 44 and 46 MIKE FORCE

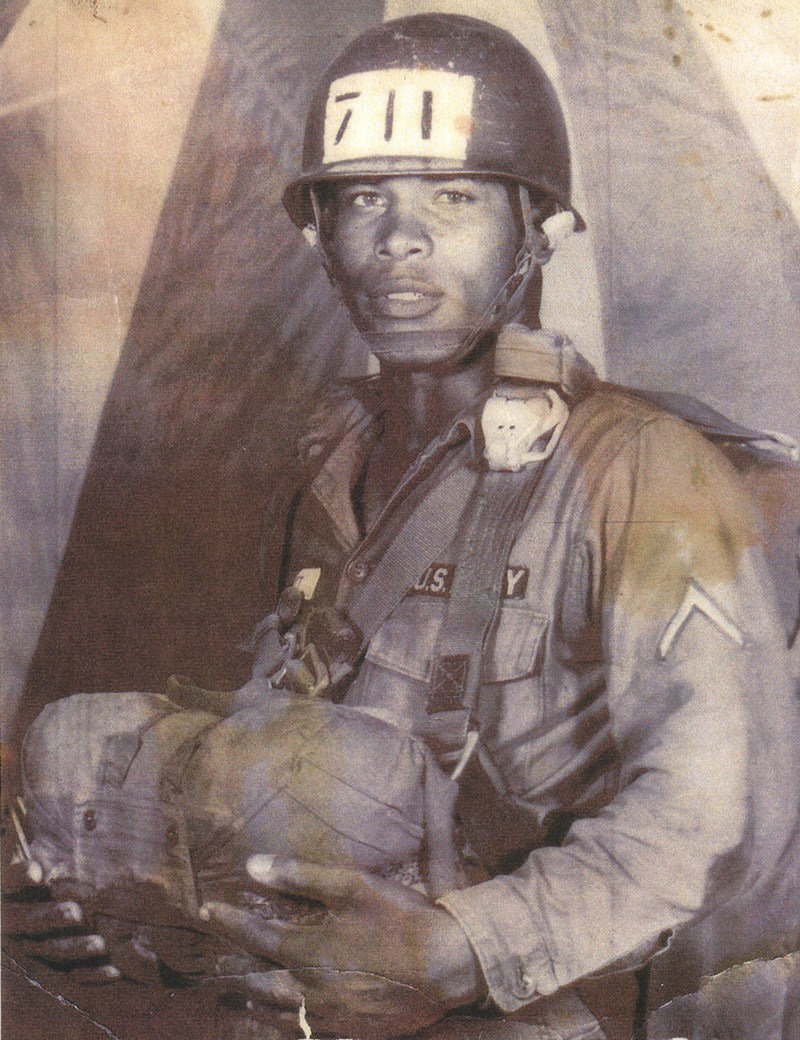

I did not go home in June of 1966. I was a platoon guide all the way through training, and now I would go to Leadership Training School at Fort Gordon, Georgia, for two weeks instead of going back to New York City. Within the next ten days would be jump school at Fort Benning, GA. My number as a jump student, the infamous #711, and then to Vietnam.

John Nesbitt, Jump School Graduation portrait, June 1966, Ft. Benning, Georgia. (Courtesy John Nesbitt)

AUGUST 18, 1966, IN COUNTRY, my brother David’s birthday: heat, dust, and humidity; an acute sense of my flesh surface awakening over the next three days. I was recruited out of Ben Hua, Repo Depo and sent to the 5th Special Forces Forward Operations Base [SFOB] in Nha Trang for examinations for two weeks. I was tested each day; one day equaled a month block of instruction; no test failures allowed, or you were shipped out! Theater-to-battalion-level operations orders and Secret Operation orders comprised the curriculum, along with night duty and security assignments on the perimeter, where we received probing fire and periodic Sapers, began my September of 1966. My green beret was awarded, and I was assigned to Detachment B-52, Delta Project, along with Robert Crenshaw, of Yuba City, California.

Within hours after graduation, I was reluctantly signed in by my 1st Sergeant at Delta Project; the ole-timers resentment was immediate:

1. A college boy

2. A Nigger and,

3. Not from training group stateside.

“What the fuck we comin’ to?” voices rattled through the office as I left to my hooch.

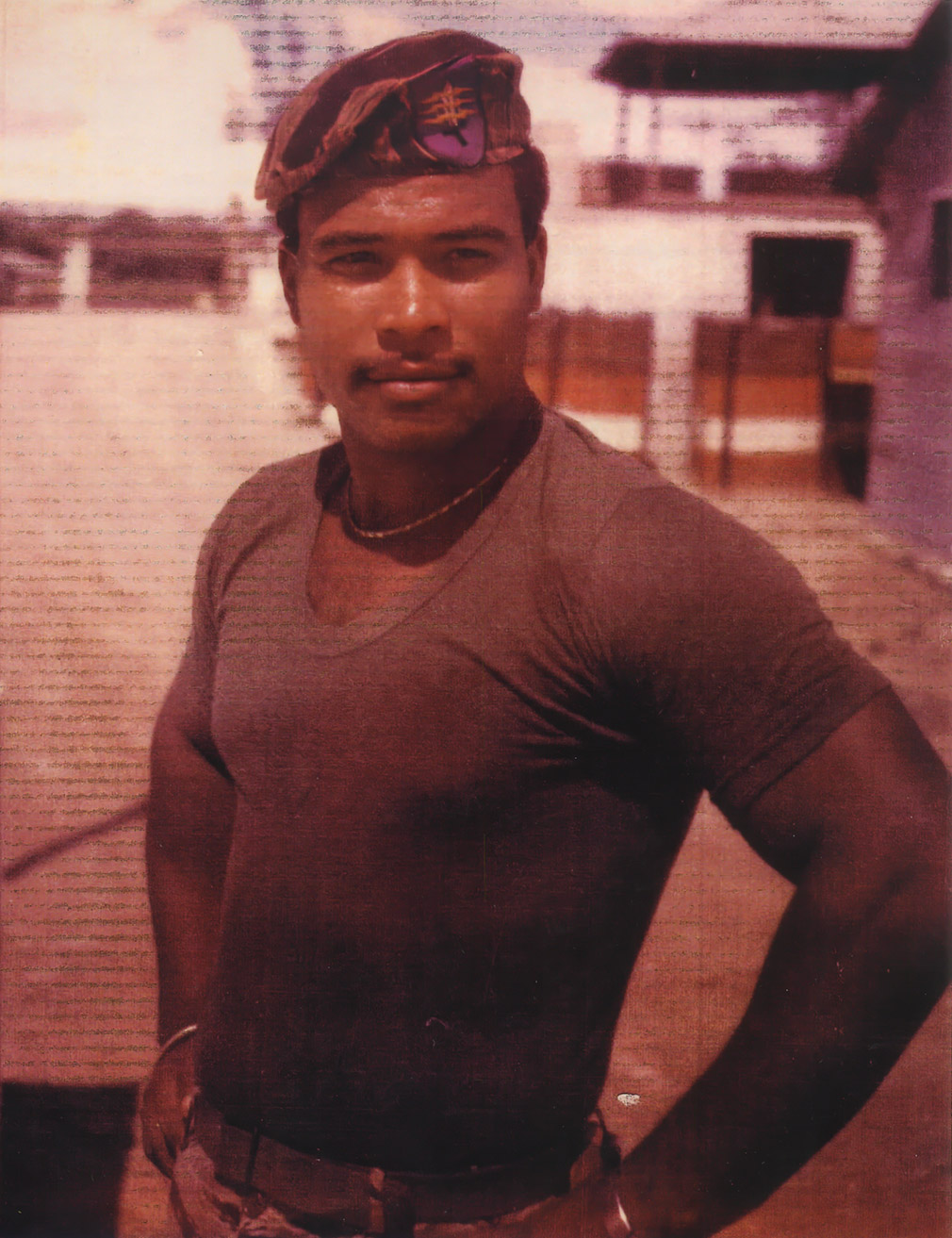

John Nesbitt, 1966, B55, CIDG/MIKE Force, Nha Trang Valley, Ban Me Thuot. (Courtesy John Nesbitt)

1st Action

After returning from my first seven-day mission, in which I was almost kicked out of SF for firing my weapon accidentally, I was called to the Opns room, “Bring your weapon!! You’re going on a break through at Phu Bai, A-102 South of the DMZ, in I Corps.”

The Viet Cong is preparing to overrun the camp. We ride a chopper to Da Nang refuel and pick up two assets one ARVN and one LLDB Lieutenant. Things felt bad from the beginning. I was new, and still taken with the country side, the colors, as an artist I was caught by the lush beauty. Our briefing plan was to spear a path into the A-camp and open an E&E route out of the camp at 180 degrees. We were prepared for sixty people to exit by our penetration. There were two LZs to use in tandem: (A) LZ was primary at 180 degrees from the camp, and (B) LZ was at a 90-degree angle from the penetration point.

The LLDB lieutenant took charge immediately on the ground; we had 34 total reaction forces, including five Americans. 1st Lt. Nuk led the column and gave the ARVN the azimuth to follow; he then began dropping back. The terrain was moderate to thick, so we had to stick close. Speed to the penetration point was the focus, and swiftly and as quietly as possible, we moved. I could feel everyone at once—not any one specifically, but all of us at the same time. In the distance, I could now hear the small arms rattle and the deep grunts of heavy mortars. I no longer felt anything except my breath and movement itself. The closer, the louder the sounds, the more off the azimuth we went. We dropped down into a gulch—not good, I thought. I slowed to check the azimuth on my compass. We’re off!!! And why is Lt. Nuk next to me? And moving away? I’m about 16th or 17th in line. I heard a B40 rocket go off, along with screams and some words in Vietnamese and American voices, and like raindrops, the sounds of AK47 pops flooded the gulch. A crescendo of small arm fire lasted about five seconds, and the voices were Vietnamese, all yelling at this time. I was in a complete, flat-out run back to the rally point.

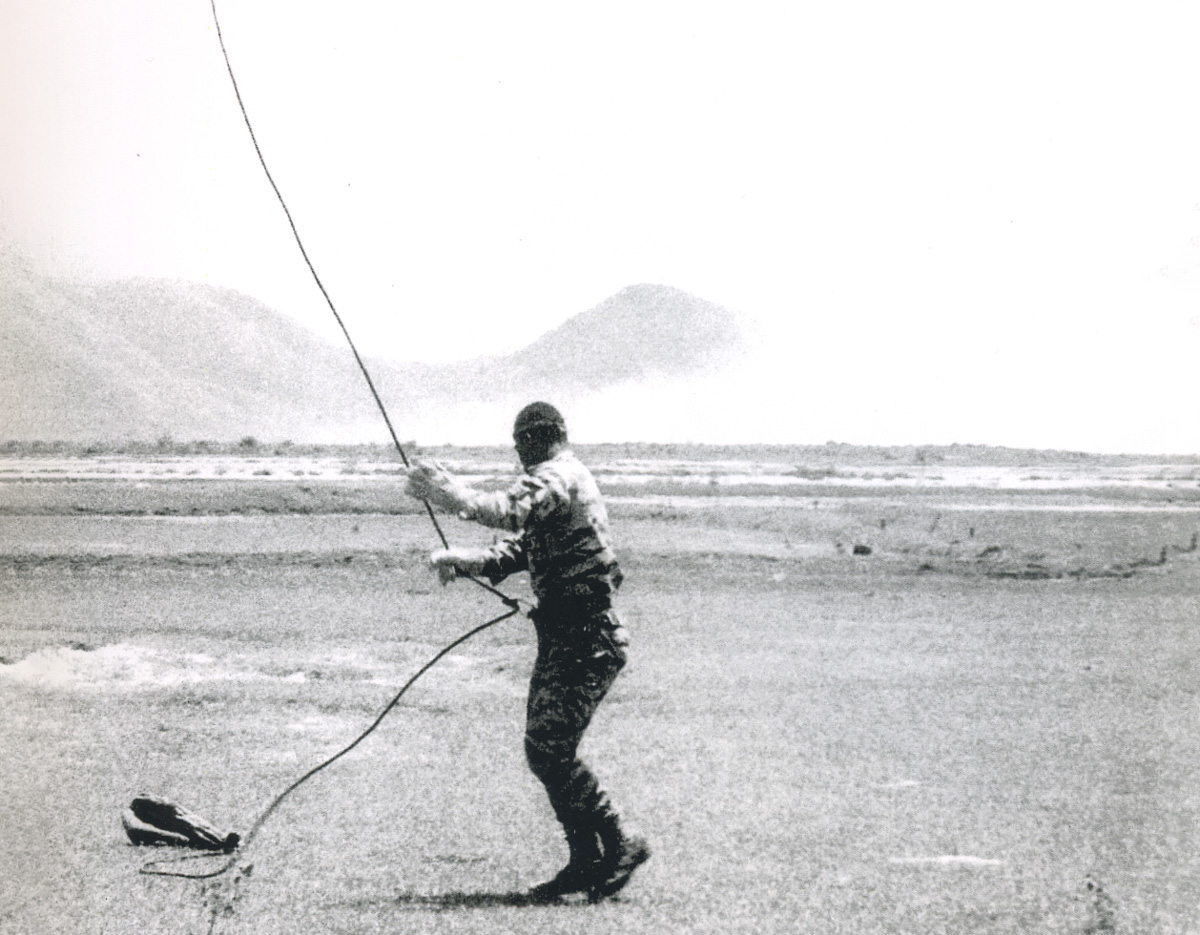

Team infiltration, by rappel, ropes out. (Courtesy John Nesbitt)

Within seconds, one other American arrived, a Spec 4 Miller from supply, two other Americans arrived, and around eight ARVN troops. That’s ALL? Of 34, we now have twelve people! The call went out to the choppers to return immediately; they couldn’t be far, we were on the ground for maybe ten minutes.

I assessed the situation for myself, although Lt. Nuk suddenly again took charge. The Primary LZ is 180 straight back; Lt. Nuk says to go for the alternate at 90 degrees; this will create a parallel foot race to the alternate LZ. We will all get shot, or we could go back to the original LZ and set up quick ambushes on the way, but only if they are chasing us from behind! We should control the move to the LZ, but Lt. Nuk says “go to the alternate” … I say “NO WE GO BACK THE WAY WE CAME!!” Calls go to the choppers to return to the primary LZ. Angrily, Lt. Nuk started to say something, and without thinking I gave him a fisted right cross knockout punch to the chin and led the return to the original LZ.

The other Spec 4 now took the lead, and I returned to the rear to set an impromptu ambush. It took four to five seconds. I could hear the brush beating behind us. An ARVN was next to me; I didn’t even realize he was there, my asshole was so tight. Before the images became faces, we emptied our weapons on the forms… got up and ran. At the edge of the LZ, we stopped, dropped, and fired our weapons again at the area we thought the VC should be. It suddenly became quiet. As we got to the choppers, small arms began to pour in on us again. I was the last to get on… I saw Lt. Nuk hanging off the back of his radio man. As he began entering the chopper, his back exploded, a B-40 rocket, two of them, one hit Lt. Nuk, and the other went through the opening of the chopper and out the other side.

So, along with me, one other American and six Vietnamese arrived in Da Nang out of a 34-man reaction team. A successful ambush against a reaction team, very suspicious. After a short debriefing, I thought I could relax. I might be court marshaled now that the after-action report was filed that I punched Lt. Nuk, and in turn he was killed as a result of being incapacitated by me at the rally point; he was ‘punched out,’ that’s why he was being carried, and was subsequently killed being assisted onto the chopper.

They would plant the blame on me was the ‘in camp’ speculation.

This is the beginning of extreme anxiety for me.

October 1966, Delta Project Recondo School

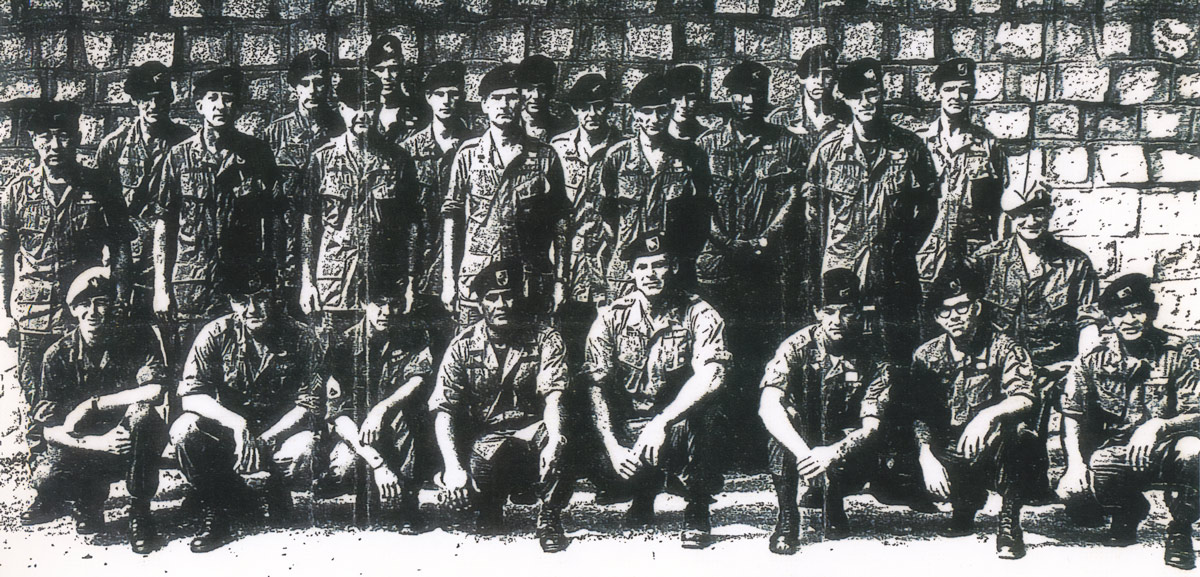

The first Delta Project Recondo Advisor/team leaders graduated at the new MACV Recondo School.

Mission: to instruct allied and friendly forces in the technique of seven–man team, intelligence reconnaissance patrolling, and information gathering techniques.

The rotation was as follows: teach and physically train five days, enter isolation two days, final operations order on the fifth or sixth day, and infiltrate day six at EMNT, i.e., Early Morning Nautical Twilight, or BENT, Beginning Evening Nautical Twilight. Carry out missions for six point five days, exfiltrate the seventh day, debrief day seven and eight, if necessary, clean weapons and equipment, and you are off for two days if lucky.

Sgt. John Nesbitt completed 14 Recondo missions from October 1966 through June 1968. The life expectancy for a LRP team member is 8.

From October 1 to December 17, 1966: 4 missions

From December 17, 1967, to May 28, 1968: 10 missions

July 1968, at Detachment A-401 Mekong Delta, Sgt. Nesbitt was awarded the Air Medal for 4,000 hours of air combat assault time logged.

RS 1 — October 1966

Team Leader, Asst. Team Leader Spec 4 Nesbitt: land infiltration, U.S. Marine Corps LRP team, seven days, just south of Da Nang near Quy Nhon, two evasion incidents from Viet Cong, no casualties.

November 1966, I experienced my first “can’t sleep, stay awake at night.”

RS 2 — November 1966

Team Leader, SSG Mrsitch, Asst. Team Leader Spec 4 Nesbitt: walk in infiltration, 4th Infantry Div. LRP team, seven days into operation area west of Quy Nhon.

Day four, as I rested during ‘Poc time,’ a Viet Cong wandering back to his camp walked up on me. I heard his approach and raised my 357… For an instant, we looked at each other. As he stumbled over my foot, I fired a single round. I saw myself falling as he fell to the ground, and immediately we were up and running. Our E&E rout now in effect; choppers were called, and we were extracted within four hours, with no loss of American lives. At this point, I have given myself up to being dead.

RS 3 — November 1966

Team Leader, Spec 4 Nesbitt, Asst. Team Leader, Spec. 4 Robert Crenshaw: Nha Trang valley west of Ban Me Thuot, 24th Infantry LRP, air infiltration, mission: to identify Ho Chi Minh Trail outlet and cache points.

Day five, first morning movement, walked head-on into an NVA scout team. Our immediate reaction drill killed the first two of about nine. We ran and set an immediate impromptu ambush while distress calls were made ground to air. No sound; within ten seconds they are moving to our flank, but which one? I follow the procedure requiring a right turn after 30 seconds of running and wait. We eased our way to an alternate LZ for pick-up while reporting information SITREP data. The LZ began to echo with voices; another patrol had been summoned, it seemed, because both sides of the LZ were giving probing fire. A fix as to the NVA location was given, and gun ships engaged the ground while I scurried my team from the point to go for the choppers. It took too long; the NVA were on us with AK fire, two of my team dropped; while helping the two wounded to the chopper, one chopper was downed with three of my team on board. Now we are out in the middle of the LZ, shooting at the first group that spotted us. This was not a stand-up-and fire situation, but with three of us left, I gave cover fire with the other two heading for the chopper.

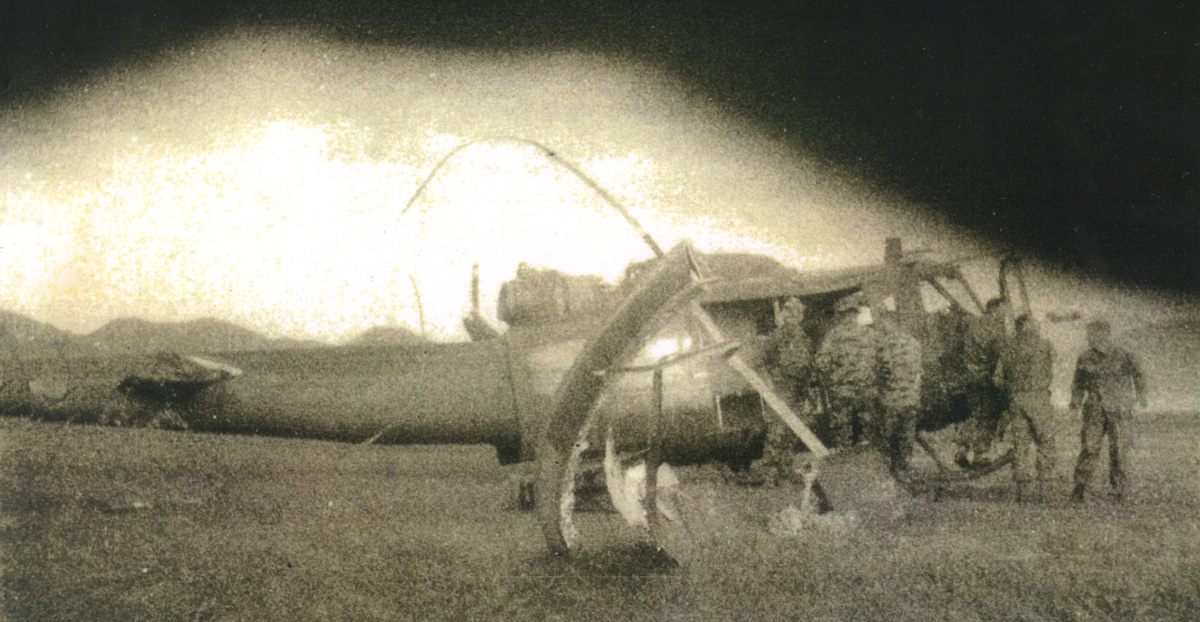

Last day of mission, rifle shot identifies our position to the NVA. (Courtesy John Nesbitt)

Once we were all in, I looked at the ground. The chopper was burning, and figures were approaching with weapons blazing. Now self-regret and questioning begins, an attempt to sum up what happened. The ride back was beautiful. I could lose myself in the cool air above the jungle and avoid the temptation to throw up and cry.

I realize the decisions I made were okay; the LZ had to be cleared or at least engaged before we could approach the choppers. I didn’t talk to anyone; the SF people didn’t talk to me about my missions; they talked only to themselves. I was the first black Recondo instructor team leader.

I let go of past disgust and renewed it with a determination to go this alone.

The Death of SSG SMITH

One hour after I began to unwind, my name was called to report to the operations room. A B-55 MIKE force was being readied to go after the patrols we rousted up in RS 3. In two hours, I was back at the LZ I had left that morning. We were in a circle with perimeters covered, and assignments for night watch were being given, when probing fire came from the southeast of our location — shit, I was going to make me an MRE, Chile Con Carne.

Because it started out as a probe, I rolled over on the ground, thinking this would be a short one.

I heard a RFPF guy run by yelling for BOXY (doctor). “All right, get into action,” I thought, so up and running I go. I stop short when I see SSG Bott leaning over an American on the ground. I lean over him. His breathing is short and his body is clammy and cool, so shock is setting in fast. We search for holes. There is an entry to the right chest and shoulder and exit wounds behind the chest, so I turn him onto the side of the wound and treat for a sucking chest wound. SSG Bott is by my side; we worked together when a Viet Cong ran past us. Now SSG Smith is turning purple, blue, and gray. I laid down in front of him and yelled at him to hang on at the top of my voice. I could see the energy drain from him and the transition from life into the other side. I was very drained and sick to my stomach the rest of the day. Even while firing my weapon, I felt the pointlessness of the war and separated from my body.

That night we experienced several short rounds, and I now understand the misery of the machinery of war.

I returned to Nha Trang on a chopper the next evening. The Viet Cong were eventually kicked out of the area, it made Nha Trang Valley safer. SFC Paul Tracy questioned me about SSG Smith’s death; they were close friends.

RS 4 — December 1966

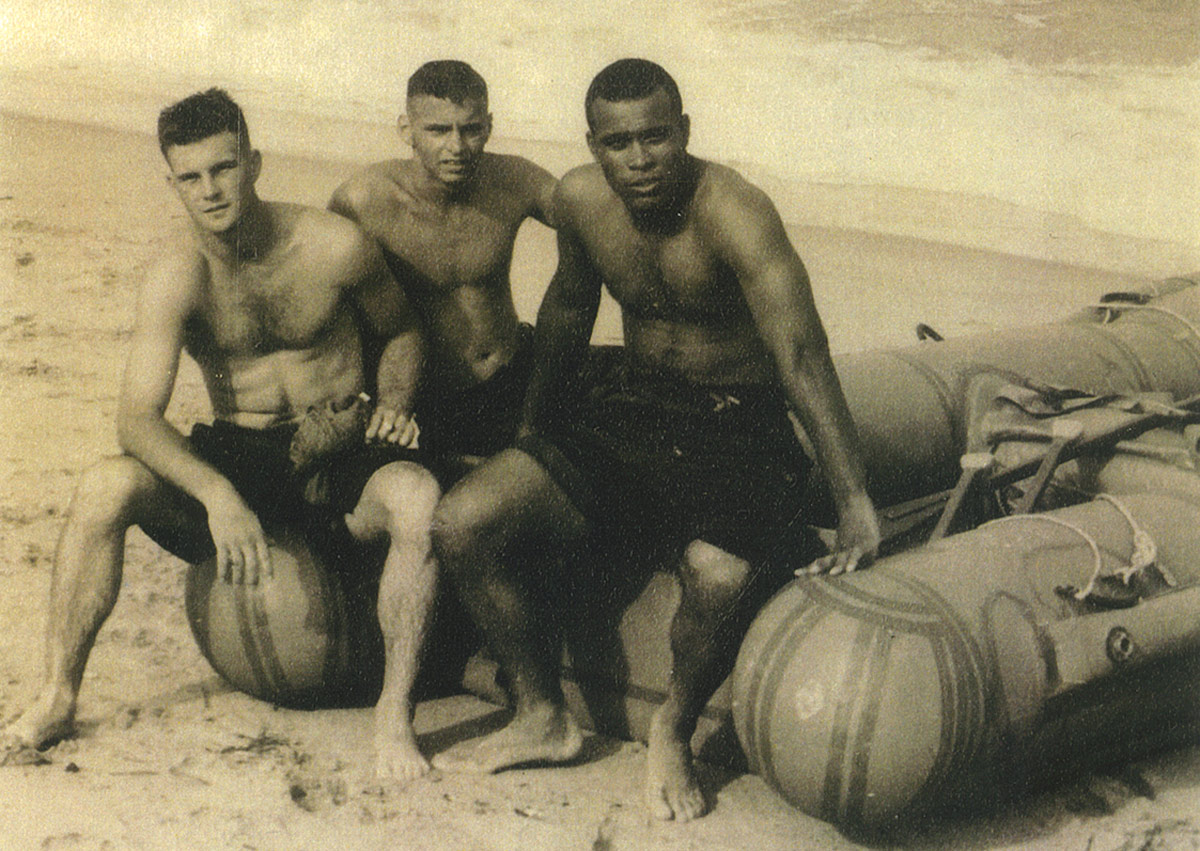

Team Leader, SFC Charlie Telfare, Asst. Team Leader, Spec 4 Nesbitt: Water infiltration, what seemed to be just below Nha Trang Harbor, and the mission was to gather information on sea infiltration points by the Viet Cong. A unique situation here — we were to infiltrate by RB 15, with the help of the Navy swift boat along with a U.S. Marine Corp LRP team.

Preparation from Nha Trang Harbor started at 0800, December 1966. At last light, the Navy swift boat took to the sea three miles out. We acquire our infiltration location, and at the Beginning Evening Nautical Twilight, we strap our gear to a single line running the length of the RB 15 (Rubber Boat 15 persons). Two SEALs swim in about a mile to shore and set a boundary for us to row to. The waves flip us over and thrash us into the rocks and beach, causing confusion for about ten seconds. The SEALs show up, we cut the gear line, release air, and begin pulling the RB 15 back to sea. We move into the brush and stop, listen for three minutes, and then, wet and chilled and eyes wide open, we set up for the night. At first light, we start a cautious listening period; our direction is strictly by compass. Now light is upon us, the day is starting, robot slow we move till midday and stop. Our objective here is mainly the perfection of patrolling and information gathering.

By the last day, we could hear periodic small arms fire; we were being tracked! If I recall correctly, the team spent the night next to a beach, under some bushes, alert for our trackers. We were picked up by chopper from an out-of-the way beach site and returned to Nha Trang. I still felt like a rookie. It was Charlie Telfare that I watched closely the whole mission; he had been with the Delta Project teams, and they truly were the experts in the bush. It would be thirty years later that I would talk to Charlie again, and how we got reintroduced is a unique story in itself.

IN THE AUGUST SENTINEL —

John Nesbitt’s story continues beginning with an account of a special operation with the members of the Australian Special Forces, and continues with his accounts of Recondo School missions and his assignment to Det A-401 in the Mekong Delta, 300 yards from Cambodia.

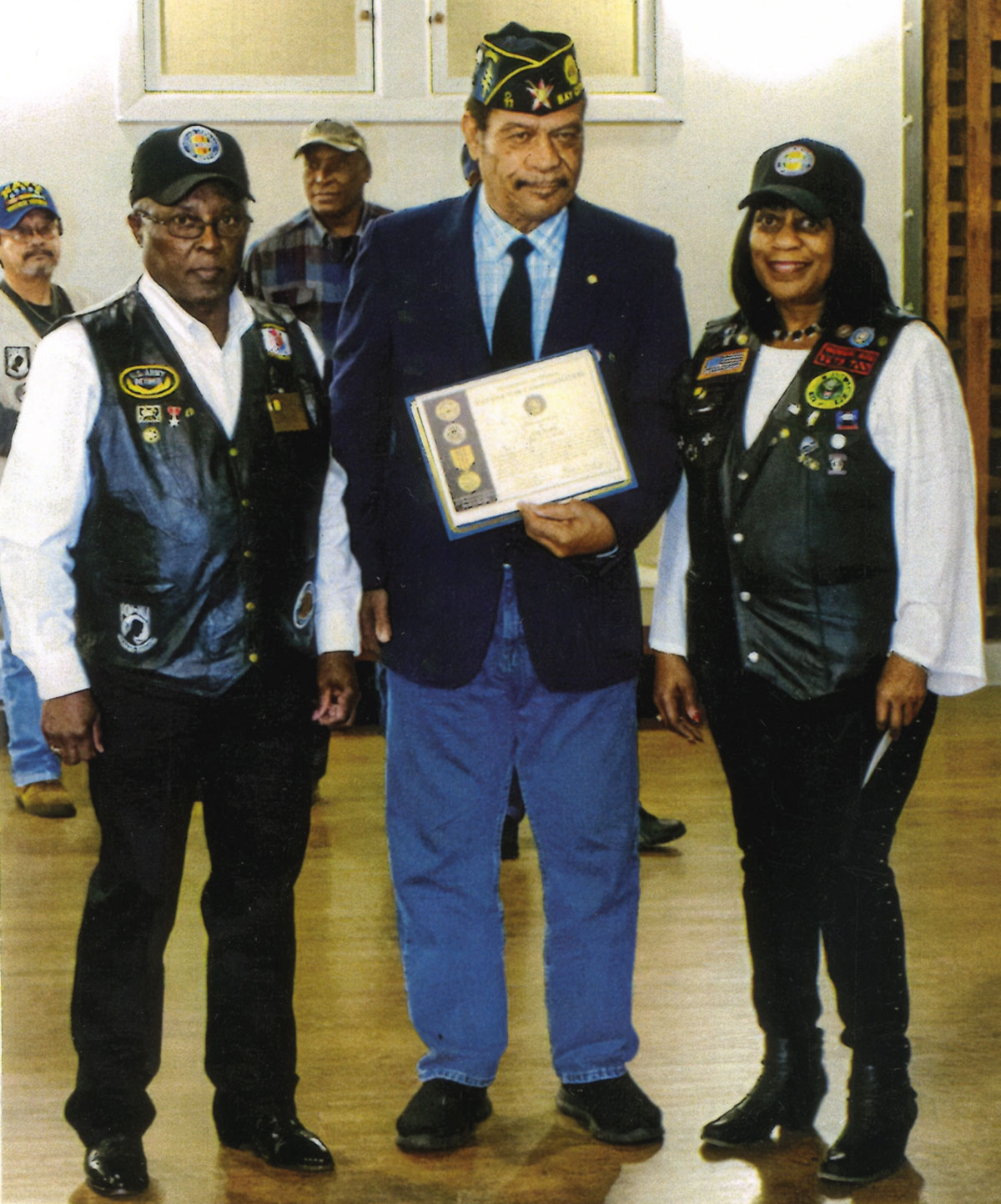

John Nesbitt with representatives of the US Soldiers Association — to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Tet Offensive, John Nesbitt received both a bronze star for valor and the air medal. (Courtesy John Nesbitt)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

John Nesbitt enlisted in the U.S. Army in January of 1966 and was deployed to Vietnam on August 18, 1966. He was recruited by the Special Forces and sent to Project Delta for reconnaissance training. He completed two assignments with the unit: September 1966–December 1966 and December 1967–May 1968. He became the first African-American advisor for the MAC-V Recondo School, where John completed 14 missions. Subsequently serving with Detachment A-401 in the Mekong Delta with the “Don Phuc Mike Force,” he went home in October 1968.

Upon discharge, John continued his education, earning a BS in Secondary Art Education and a Master in Fine Arts (MFA). He taught at several schools, including Grant Union High School and Hampton Institute, College of Arts and Letters, in Hampton, Virginia. As a Case Manager for the Mather Community Campus in Sacramento, John initiated a Resident Council and Community Garden.

John’s commitment to community service work has been demonstrated by his full involvement with the Retired Senior Volunteer Program (RSVP), the Neighborhood Emergency Training (NET), and the Veterans History Project (VHP). His contributions to these groups led to his selection by the Bank of America as one of five “Local Heroes” in his community. He also received Congressional recognition as a Sacramento Regional Community Trainer.

John is also a fine artist whose oil paintings have been displayed at various galleries throughout the US. He is also a Tae Kwon Do master with 7th Dan certification and has operated a training school that offered special youth programs.

John Nesbitt has raised two children and is currently living in the Sacramento area.

John Nesbitt’s VHP interview about his military service can be viewed at https://www.loc.gov/item/afc2001001.38179/#item-service_history

To learn more about John Nesbitt visit his website at https://www.jnesbittandassociates.com/index.html

Leave A Comment