The Real Son Tay Raid —

51 Years Later

51 Years Later

Note: If this is your first time reading this entry, please read “Investigating the Son Tay Raid — The Devil is in the Details” which appeared in the March 2022 Sentinel. It contains some clarifications and corrections to some of the information in the following entry.

Forward

In July 1997, I enjoyed the opportunity to spend several weeks at Ft. Bragg with the Army’s Special Forces Command. While there, I delved into Operation IVORY COAST, gathering up additional and exclusive facts which further enhanced what has already been published on the subject from credible sources.

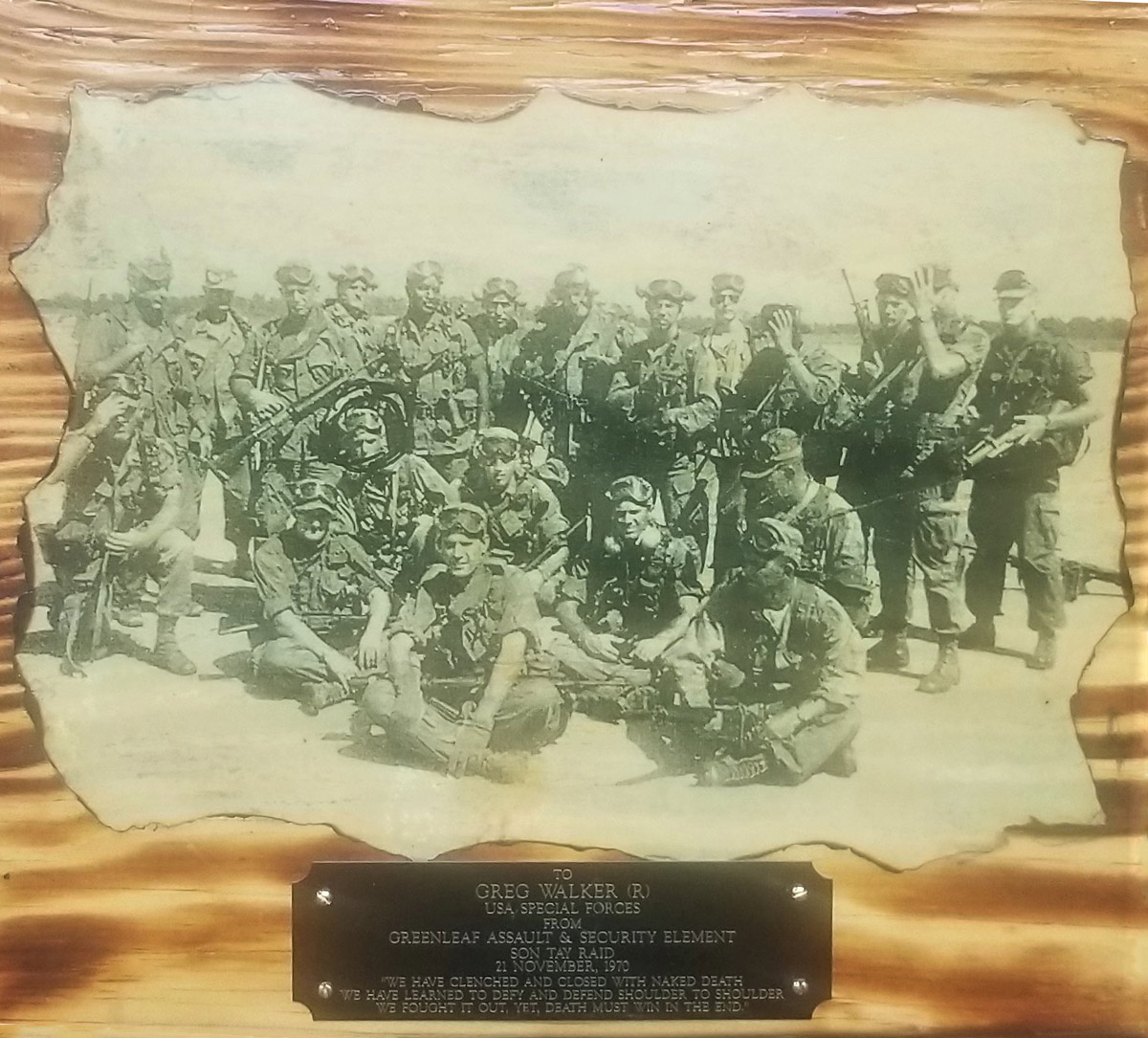

In 2017, I spent a relaxing week with retired Sergeant Major Vladimir “Jake” Jakovenko, who was with the Greenleaf Assault and Security Element during the Son Tay Raid. Jake added more to the story, his recollections priceless.

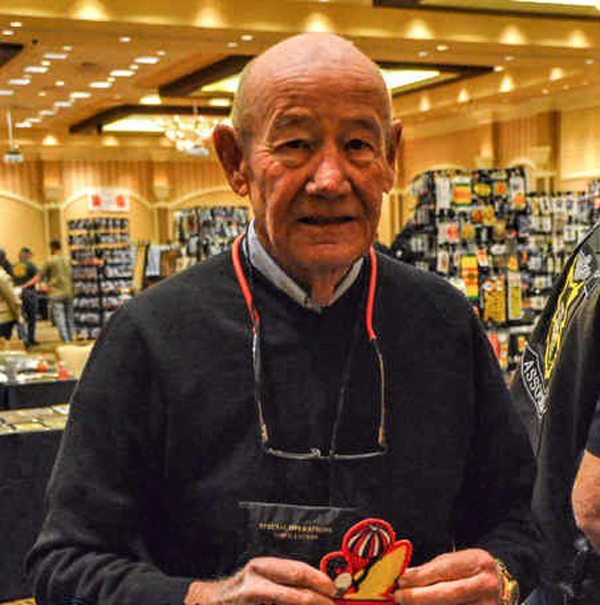

Author, Greg Walker, with Son Tay Raider, SGM Jake Jakovenko (photo courtesy Greg Walker)

The Son Tay Raid is a tribute to exceptional personal courage and commitment. It is also the epitome of long-range raid planning, preparation, and execution. Its many successes are well understood by those in the special operations community. The only smoke and mirrors involved were designed by those warriors who carried out this extraordinary assault into the enemy’s heartland against those who bore the brunt of its fury.

This article is dedicated to the memory of my dad’s and my friend, Jim Butler, founder of the Special Operations Association (SOA #001). RIP, Warrior, RIP. You are missed.

The Real Raid

Charged with conducting unconventional warfare in North and South Vietnam, as well as Cambodia and Laos, the special operations group, SOG (Studies and Observations Group) consisted of three field commands. These were Command and Control North, Central and South. CCN was always the largest of the three commands and its missions included cross-border operations, the tracking and attempted rescue of POWs, agent networks and psychological operations directed against the North Vietnamese.

The first successful SOG project was SHINING BRASS, whose commander was former WHITE STAR project officer Col. Arthur “Bull” Simons. Both WHITE STAR and SHINING BRASS were extremely successful special operations conducted under clandestine/covert circumstances.

By 1966, Simons was serving with SOG as commander of OP-35, a project responsible for all cross-border operations into Laos, Cambodia and later, North Vietnam. Retired General Jack Singlaub recalls assuming command of SOG from Brigadier General Donald Blackburn, who commanded SOG in the mid-60s. “When Don left to become the SACSA and I took over SOG in 1966, Simons was in charge of OP-35.” Two officers Simons worked alongside during his OP-35 tour were Dick Meadows and Elliot Sydnor, both of whom would later be handpicked by Simons to lead teams “Blueboy” and “Redwine” into Son Tay.

Blackburn, who became special assistant for counterinsurgency and special activities (SACSA) in Washington D.C. after his tour as “Chief SOG”, was the final approval authority for all SOG operations passed from MACV through the commander in chief Pacific (CinPac) to the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) in Washington, D.C. The importance of this direct linkage between SOG-CCN commanders/operators and Operation IVORY COAST (Son Tay) has long been overlooked by those studying the raid. However, it is perhaps the most important factor in the raid’s equation, as we shall soon see.

In a 1992 interview conducted between this writer and General Jack Singlaub (ret.), General Singlaub offered a raid against Son Tay had been studied by SOG in late 1968, nearly a year and a half before IVORY COAST would be launched. Son Tay as a POW compound had been discovered during OP-35’s BRIGHT LIGHT missions, meant to rescue POWs from suspected sites in Laos and North Vietnam. Over two hundred such ops had been run with no successful conclusion. SOG’s OP-34 was responsible for escape and evasion networks inside North Vietnam and was administered by the Joint Personnel Recovery Centre (JPRC). Between the two projects a great deal of hard intelligence about both the ground and the enemy was collected and updated, passed on to MACV-SOG, the SACSA, and then JCS.

Years later, an army helicopter pilot who flew recovery missions for CCN would say this of Butler, “I used to hate hearing Jim whispering to us on the radio. He’d say ‘come and get us’…and you knew he and his team were sitting right in the middle of the NVA watching them. It was some of the hairiest flying I ever did going after Butler.”

Singlaub confirms SOG began planning a raid on Son Tay during his tour as commander. “…as best as I can recall, I‘d left SOG before it was completed,” says the general. The study was wrapped up under Colonel Steve Cavanaugh, who replaced Singlaub at SOG. It was presented for operational consideration but turned down. Today, Singlaub believes the decision was a wise one. “The serious (intelligence) leak at the (South Vietnamese) minister’s level likely would have compromised the mission either before it got underway, or once it was on the ground inside North Vietnam.”

Again, what is critical to remember at this point is SOG’s already researched plan for assaulting Son Tay as early as 1967. This plan, along with the operational presence and participation of SOG-CCN’s earliest operators, would become the foundation for Operation IVORY COAST launched three years later.

Singlaub believes SOG had the personnel and equipment capable of successfully undertaking a raid in Son Tay. Keeping the training and the plan secret would have been the unit’s greatest challenge as SOG was essentially in-theatre, with all the drawbacks such close proximity holds. “Son Tay was no secret to us,” confirms General Singlaub. “We knew about its status as a POW camp well over a year before the (1970) raid was launched.”

The particulars of Operation IVORY COAST are superbly documented in both Benjamin E. Schemmer’s work on the subject (The Raid, Avon, 1976) and At The Hurricane’s Eye (Greg Walker, Ivy Books, 1994). Not available in Schemmer’s account of the Son Tay and published for the first time in “Hurricane”, is the American led SOG recon mission into Son Tay prior to Simon’s launch from Udorn, Thailand.

Seventy-two hours prior to Simon’s hitting Son Tay, CSM Mark Gentry was told to cancel one of his project’s Earth Angel missions. Earth Angel operators were Vietnamese dressed in enemy uniforms while penetrating North Vietnam for the purpose of gathering intelligence. As they operated far behind enemy lines the most often used method of infiltration was by high altitude-low opening parachute drops, or HALO. Gentry’s Vietnamese team was scheduled to freefall into the Son Tay area when their mission was cancelled with no reason given. In 1994, Gentry said he was told after the fact the cancellation was due to IVORY COAST.

In interviews with Jim Butler, identified in At the Hurricane’s Eye as “Frank Capper”, One-Zero for RT Python, the Earth Angel mission was scrapped in favor of an American led recon. This team was made up of three CCN One-Zeros, two North Vietnamese Kit Carson Scouts from the Son Tay area and one CIA operative. The team launched from CCN’s HEAVY HOOK mission site along the Thai border. Due to HEAVY HOOK’s helicopters being heavily armored their range of operations were limited. The team was therefore loaned one of Simon’s now pre-staged reserve helos in order to get to Son Tay.

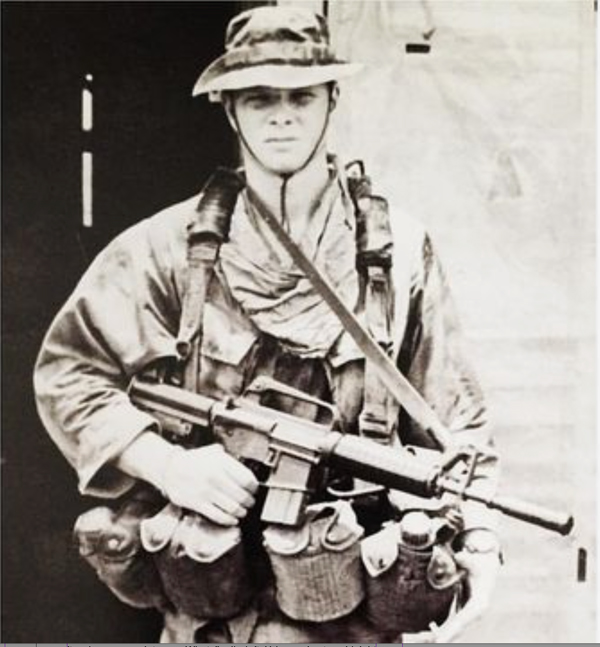

Former CCN recon team leader and founder of the Special Operations Association (SOA) Jim “Snake” Butler was a BRIGHT LIGHT “One-Zero” during his five tours at CCN. “Our intelligence gathering teams entered North Vietnam whenever we wanted to,” he says today. “It was common for us to evade their (NVA) radar using helicopter flying in from several hilltop launch sites along the northern Laotian border. We pretty much came and went as we pleased.” Butler’s codename during his tours with the downed pilot recovery project known as HEAVY HOOK was “Fat Capper.” (photo courtesy Lindsay Butler)

To view the James Butler Tribute visit https://vimeo.com/567075017

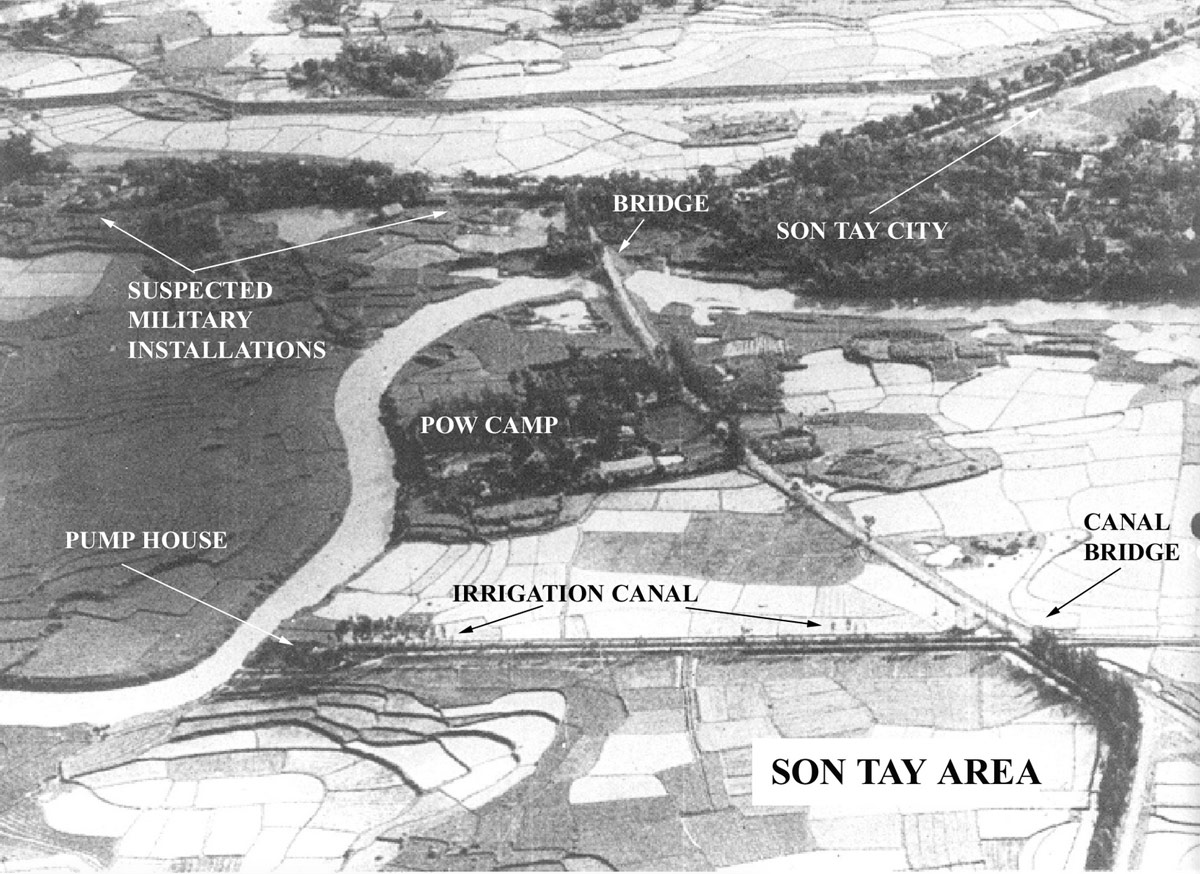

The helicopter refueled at the CIA mission support site at Longcheng, in Laos. It then infiltrated North Vietnam’s air space using one of the CCN air lanes used successfully over the years for just such operations. The team landed several kilometers from Son Tay, moving by foot to a position where it could observe both the POW compound and that of the so-called “secondary school” 450 meters to the South of the prison.

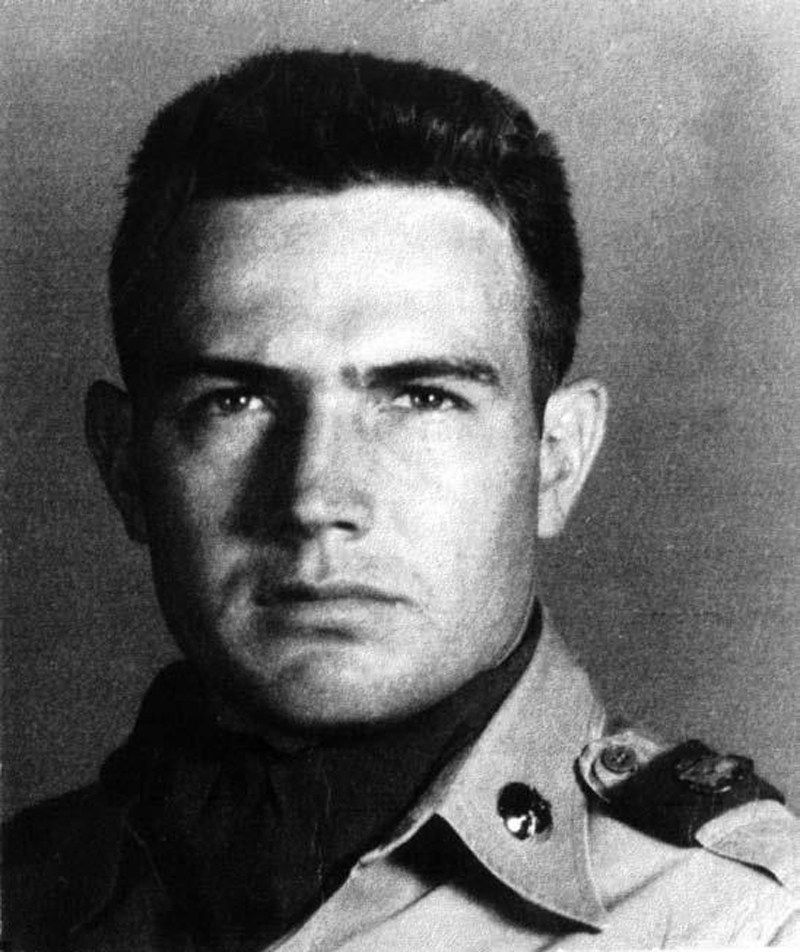

SGT Dale Dehnke (photo courtesy James Butler)

According to Butler, it was Sergeant Dale Dehnke who led the team into Son Tay. During their stay the operators confirmed specific information gathered by SR-71 and drone flights, as well as from past intelligence debriefings of local inhabitants and captured NVA soldiers gathered by the CIA. Dehnke’s team could not confirm or deny the presence of American POWs at the compound due to its prison walls.

However, they did verify the continued presence of North Vietnamese regulars at the prison. It was this guard force the raiders encountered as Dick Meadows’ assault team crash-landed inside the compound.

Also verified was the presence of both North Vietnamese and Chinese troops in and around the former school now being used as a military installation. According to my exclusive interview with the co-pilot of Simon’s helicopter the night of the raid, this installation was briefed as both a threat and possible distraction beginning at the onset of IVORY COAST’s planning. “We were told there were enemy troops at the secondary school was so close to the prison.”

This concern on the pilots’ part was twofold in nature. Their primary fear was that the two installations were so similar in layout and construction that they might be confused due to any number of circumstances. In fact, this is exactly what occurred during the final leg into Son Tay proper. The second consideration had to do with how swiftly the military personnel at the secondary school site could deploy a response force against the raiders at the prison. The 450 (+ or – 50) meters separating the two sites could be covered within minutes by either foot or vehicle and Sergeant Dehnke’s intelligence gathering mission showed those mixed troops at the former school were well armed and motorized.

Discovered also was the fact the force at the school compound stacked their weapons in its courtyard at night. This bit of information would prove invaluable to Simons’ Greenleaf team when it found itself deposited by accident outside the now-confirmed barrack’s walls.

Whodunit? CCN’s most mysterious mascot

Exfiltrating at night the CCN recon team grabbed a water buffalo calf discovered at the LZ point. According to Butler, close friend of Dale Dehnke, the “snatch” was a legendary prank. The animal was removed at HEAVY HOOK’s launch site from Simons’ loaned helicopter prior to its being returned to Udorn. The calf became the project’s mascot, with Captain Butler offering “it grew fat and sassy” with time.

It was the rumor of such a prank that landed Simon’s raiders in hot water with former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. This after buffalo dung was found in one of the helicopters assigned to the task force. As no one outside of a small cadre of the raid’s command and control group even knew of the “black” recon into Son Tay by Dehnke & Company, the investigating body charged with looking into the allegation never visited HEAVY HOOK where the animal ended up.

Dale Dehnke was killed in action on 18th May 1971, while operating in the Da Krong Valley inside Vietnam. Ironically, Sergeant Dehnke was due to rotate home and had volunteered to “strap hang” the mission assigned to newly formed RT Alaska. According to Jim Butler, Dehnke felt the new team could use his expertise as it got its feet wet. Even more ironic is the fact the NVA battalion that overran RE Alaska’s hilltop position was one of those trained by an elite cadre of Chinese advisers. These advisors were co-located with other Chinese military personnel at the former secondary school at Son Tay.

Their mission? To train and advise what became known at CCN as “headhunter” battalions; units designed to locate, track and kill SOG recon teams.

Again, Jim Butler remembers the effectiveness of these new NVA units beginning in mid-1969. “With the new enemy tactics time was what you didn’t have. Once they had our position pinpointed, they’d begin throwing human-wave attacks against it. We’re talking fifty to sixty men at a time until they simply overran the perimeter and everyone inside it. They didn’t give a damn about their own casualties, they just wanted that recon team dead.” (photo courtesy Lindsay Butler)

Again, Jim Butler remembers the effectiveness of these new NVA units beginning in mid-1969. “With the new enemy tactics time was what you didn’t have. Once they had our position pinpointed, they’d begin throwing human-wave attacks against it. We’re talking fifty to sixty men at a time until they simply overran the perimeter and everyone inside it. They didn’t give a damn about their own casualties, they just wanted that recon team dead.” (photo courtesy Lindsay Butler)

Headhunter tactics as trained by the Chinese included the use of an extensive network of trail watchers and trackers, coded signals to chase and turn the teams once they were put on the run and effective use of the roughly 500-man battalion’s human assets. SOG recon teams were so well trained and disciplined and carried so much firepower per man that engagements with larger enemy forces were commonly won as long as the fire fight was short, fast, furious and eventually supported by both gunships and rescue. This all changed when the larger, more heavily armed, Chinese advised NVA units showed up on the scene.

“Once we were compromised on the ground you just wanted to get the hell out,” recalls Butler. “My team discovered the best way to break contact was to rush right at the trail watcher’s position when he fired. Too many other teams didn’t do this, and they ended up getting waxed.”

With this in mind it is apparent IVORY COAST’s common thread was its sharing of former CCN commanders/operators, intelligence as well as assets, and a professional desire to ensure the raid’s greatest chance of success given the accepted presence of foreign military advisers whose specialty it was to engage U.S. special operations forces.

“Anybody who gets in our way is going to be dead.” — Col. Arthur ‘Bull’ Simons (U.S. Army)

On 20 November 1970, at 23.18 hours, Operation IVORY COAST was underway. With over 170 intense rehearsals under their belts the raiders and flight crews were literally prepared for any eventuality.

An in-depth review of the official after-action report written by BGen. Leroy Manor, Commander of the Joint Contingency Task Group, JCS regarding the Son Tay raid reveals no expense or limit was placed on those volunteers now headed for the POW compound.

Every item considered necessary for success had been brainstormed, evaluated, accepted/rejected/modified and then trained. The command element had selected only the best of the 300 men who’d volunteered for an unknown mission with no announced objective or incentive. Security surrounding the operation in all of its phases was intense. What finally left Udorn prior to midnight was easily one of the fittest, most combat experienced special operations raid forces ever fielded. From Armalite Single Point rifle sights and CAR-15 to Simons’ team’s “heavily overcharged” satchel explosives meant to “minimize personnel exposure and to ensure destruction of the target”, nothing had been left to chance.

The close quarters combat training of the raiders was equally demanding. Already formidable shooters the commandos’ skills were enhanced with countless hours on the range and in live fire rehearsals during the hours of daylight and darkness. By launch date they were capable of engaging an enemy force assigned to rear guard duties at a level of surprise, accuracy and violence of action previously unheard of for a force its size. This is why not only Simons’ support team (Greenleaf) but also Meadow’s (Blueboy) and Sydnor’s (Redwine) were able to kill or wound all those whom they engaged with such effectiveness.

“We’d been warned while training at Eglin Air Force base in Florida that such a mistake was possible…I wasn’t paying attention to the final checkpoints as I made our approach. I wasn’t looking for the road, or the river (Song Con), Which was supposed to be right outside the prison. When I saw the outline of the structure, that’s what I headed for.” – LTC. Warner Britton (ret.) – At the Hurricane’s Eye

The former secondary school located less than 500 meters from the Son Tay prison had long ceased to provide civilian education. Intelligence reports showed it, as well as other facilities in the immediate area, had been turned in to military complexes, or logistic centers. According to an exhaustive report (“The Role of the Air Force in Assault on the POW Camp at Son Tay, 1978”) done for the Air Force Academy by Alfred Montrem, Warner A. Britton’s co-pilot during the reinforced school-cum-military barracks resembled the POW camp.* So closely did the two appear in general nature only a two-story building at the barracks could be used as a discriminator as the prison camp had no such structure.

Manor’s report on the operation never refers to this installation as a school, or as “the secondary school”. It calls the site what it was at the time, a “military complex 400 meters south (to the right of the inbound course) of the objective…” Then Major Montrem told this writer in his first public interview in 1992 that he remembered “seeing strange radio or television antennae” atop the two-story pagoda like structure inside the complex’s walled compound during his aircraft’s multiple flights over it during the raid. Although an NVA photo said to have been taken of the complex the “day after the raid”, only one shattered building is depicted with the admonition that this single structure represented the former school. Copious aerial photographs combined with intelligence reports and the American led recon team’s own confirmation of the complex’s layout and true nature (not to mention debriefings of Simons and his 22 raiders) decry this unfortunate reporting error.

Son Tay Area Map

Note: In studying one of many photos for this story I noted all the windows have bars on them…much like a prison. Comparing the building shown in the photo with line drawings done of the buildings/cells found at the POW camp, it is most likely this structure existed at the prison, not the “secondary school”. Unless – of course – the NVA found it necessary to keep their secondary students behind bars. Also noted are the many trees surrounding the building shown. Again, line drawings made from an SR-71 and drone overflights show the prison area to be alive with trees, ranging from 20’ to 40’ tall, were discovered – by Meadows and his assault team – to be closer to twice this. (USA JFK Museum)

The Sunday Tampa Tribune (1st June 1997) carried the story of Son Tay revisited b retired Air Force officer Norm Bild. Bild, who met Meadows while attending military classes at Hurlburt Field, Florida, made two trips to Vietnam in 1995. While the first was confined to the south Bild did manage to go to what was North Vietnam the second time around.

He and his interpreter visited the village at Son Tay and spoke with people who knew of the fight. A 21-year-old Vietnamese agreed to take the two visitors to the old prison site where Bild took several photos and recovered a bit of prison barbed wire. Police arrived and detained the two, releasing them only after Captain Bild (ret.) signed a statement promising never to come back. A $20 fine was paid, making Norm Bild the only known American citizen to recently visit and photograph what had been Son Tay prison.

Bild mounted one of the photos he took of a prison cellblock along with the strand of wire he’d taken from the camp. This photo is accurate ref. The line drawings used by the raiders to train for their assault on the cellblocks. These items are today part of a memorial plaque commemorating the raid on the POW camp at Son Tay, done in memory of Major Richard “Dick” Meadows.

Why did Simons’ team land at the wrong military complex? As explained in General Manor’s official after-action report as well as this author and Benjamin Schemmer’s book on the subject, all helicopter flight crews involved in the actual assault experienced the same initial navigation drift. This error was due to the winds at the time, a factor everyone involved in flight operations was warned might happen. If it did, the under correction would put the airborne raid force online with the advisor barracks and not the prison.

As the raid unfolded the lead helo (Apple Three) pilot increased his air speed to 120 knots, somewhat adjusting his direction once released by the MC-130 Combat Talon (Cherry One) which was their pathfinder into North Vietnam. Although Major Frederick M. Donohue could not yet see the objective he dropped the formation’s altitude to 50′ above the earth and headed in toward what he believed was the prison.

Apple Two was piloted by LTC John V. Allison, whose crew was carrying Captain Elliot Sydnor’s twenty-one-man commando/security team. Code named Redwine, Sydnor and his men were to secure the southern portion of the camp as Simons’ Greenleaf team took the northern sector of the prison. Dick Meadows, whose aircraft was code named Banana, was to crash-land inside the compound roughly twenty feet from where the POWs were being held. It would be Blueboy who would blow an opening at the southern end of the prison’s east wall. This breech would be where the POWs and the assaulters would exit. To accomplish the task Blueboy would rely upon a special three-pound C-4 charge.

Banana’s wreckage was to be further demolished using a three-pound mixture of C-4 and thermite. This charge was constructed in a thirty-inch length of four inches fire hose. It was to be placed under the floor in the bilge sump between the fore and aft fuel tanks.

All the attacking teams were cross trained in each other’s assigned missions in case one or the other was unable to participate. In this case, Redwine assumed Greenleaf’s taskings once it was established Simons was not yet in position at the prison due to Britton’s error in landing him nearly half a klick off.

Alfred Montrem (U.S. Army)

Again, according to Alfred Montrem, this error came about because Britton had not participated in any of the Eglin AFB flight training, assigned as he was to the command group. Vowing to fly the mission regardless, Warner Britton possessed only 30 hours in an HH-53. Major Montrem, on the other hand, had over 1,000 and had participated fully in the Florida train-up phase. The night Bull Simons was to land at the prison compound in support of Dick Meadows would be the first time Walt Britton flew an HH-53 in to combat!

Alfred Montrem – http://www.veterantributes.org/TributeDetail.php?recordID=1590

As the assault unfolded both Donahue’s and Meadow’s helos flew over the secondary complex. Although Apple Three declined to fire the base up at the last possible second, Banana’s assault team did so with relish. It is important to note during the train up phase every consideration regarding combat effectiveness was taken into account. This also included where to place selected weapons systems in the aircraft to undertake specific targets with the most possible rounds on target with the time window available. The goal of this type of planning and training was to engage and destroy enormous number of targets both accurately and in the shortest time possible.

The secondary compound was long identified as a military–not civilian–installation. It was further known this compound housed both NVA and foreign advisors, specifically Chinese troops. It was understood this adviser element represented both air defense and special operations personnel, whom the NVA guard and support force were responsible for protecting/servicing. Overall, it was projected in light of both ground and aerial intelligence estimates that no less than a company size element (60-90) would be found at this compound. The ability of this force to respond immediately to the POW camp by either foot or vehicle could be counted in single digit minutes. The compound was originally one of those targets assigned to a sortie of A-1 Skyraiders whose role it was to fly close air support for the raiders.

With this in mind, how did Simons and his force indeed wound and/or kill what has been estimated to be close to 200 enemy soldiers during Greenleaf’s nine harrowing minutes on the ground? For the first time we now know the answer.

Richard “Dick” Meadows (U.S. Army)

When did Dick Meadow’s assault team fired up the compound it did so under the following circumstances. During the train-up phase, intense attention was given as to how to utilize the helicopter platforms’ firepower to its best advantage. Per the official after-action report on this subject “A need was recognized for additional skills in firing machine guns and shoulder weapons from the assault helicopter in flight during its landing phase.”

The HH-53 platform was chosen over the UH-1H for a number of reasons. One of these had to do with accurate, sustained firepower. “During the test many changes were made in individual firing positions in order to arrive at a system that would allow maximum number of rounds placed on the high threat areas (the gate and NW tower). With this consideration in mind, left-handed shooters were placed in position to give greater accuracy and longer engagement period.”

The report says, further that “The HH-53 helicopter allowed on 7.62mm machine gun mounted in the left front window and ten shoulder fired weapons positioned in the windows, right door front door and on the ramp to be fired. This system provided excellent accuracy and 360-degree target coverage.”

What this did was permit the assault team to deliver a minimum of 100 rounds of M60 fire on to the target, as well as three 30 round magazine per man of 5.56mm ammunition during the final landing phase. With over 1000 rounds of highly accurate fire striking anyone or thing unfortunate to be caught sleeping, the initial body count would be impressive. This is exactly what occurred when Banana’s well-trained team/crew opened up on the interior of the secondary compound’s inhabitants.

A most kind and generous handmade gift from SGM (ret) Jakovenko after our visit. (photo courtesy Greg Walker)

In late 1978, SGM Jakovenko and members of his Special Forces ODA provided the color guard at the burial of their close friend and Vietnam veteran, SP4 Michael D. Echanis. Mike was killed along with SGT Chuck Sanders, also a member of Jake’s team, in Nicaragua. After the services Jake removed his ribbon bar, to include the Silver Star he received after the raid and gave it to the Echanis Family. It resides in the shadow box Ms. Liz Echanis, Mike’s sister, had made in her brother’s honor. (photo courtesy Liz Echanis)

Watching the compound and not Meadow’s helo, Warner Britton failed to follow the rest of the flight as it made its way over to the POW compound, the navigation error corrected by Apple Three’s pilot and noted by Banana’s crew. At H+1 minute Britton dropped the ramp of his helo and Greenleaf exited. Almost immediately a half dressed, dazed NVA guard ran in to Simons, who shot him dead with a .357 revolver.

The Headquarters element was exposed to “automatic weapons fire” and elected to penetrate and assault the compound. From the intelligence updates received Greenleaf’s personnel knew who, what, and about how many bad guys they had inside. They also knew the element of surprise was lost at the POW compound due to the assault team’s inadvertent firing up of the wrong camp. Once inside, the assaulters cleared “the billet at the southern end of the compound utilizing concussion and fragmentation grenades and rifle fire accounting for ten NVA soldiers killed.”

The fire team elements were advised by Simons that extraction and reinsertion was imminent. By H+2 minutes the compound had been penetrated and the fight was on. At H+3 minutes Element 1 secured the landing zone and provided protective fire to south and west. Element 2 was taking automatic weapons fire as soon as their boots hit the dirt, so it moved in an easterly direction, taking enemy troops located on the road east of the compound under fire.

From H+2 to H+5 minutes the Headquarters Element continued to fight its way through the compound’s southern billets. According to the report, “More enemy personnel than expected were encountered and a large volume of automatic weapons fire was coming from the two-story building located in the center of the compound.” A gunner from Element 1 detached himself and placed accurate M79 grenade fire on to this threat, knocking it out so that by H+3 minutes…this billet was secured.”

With the two-story building, later confirmed to be the compound’s armory, cleared, Element 1 now came under fire from the western edge of the camp. This time an M60 machine gun was brought up to silence the opposition. Element 2 began moving down the road outside the compound, killing and clearing armed opposition on both flanks in a northerly direction for roughly 150 meters. Due to the fury of the fight, the fury of the fight, the distance involved and the darkness, no enemy confirmed kills could be judged over the course of the fire fight.

Simons directed this element’s leader to “close and secure the south-east portion of the extraction LZ”, and at H+4 minutes the element began this movement.

With only 26 minutes available to the raiding force Bull Simons later said he was only concerned his people would miss out on the main assault at the POW compound. At H+5 minutes the Headquarters Element was just finishing its engagement of more enemy personnel than expected by clearing the southern end of the two adjacent billets “with fragmentation grenades”. Four NVA soldiers made a break for the already silenced armory and were gunned down as they left the short-term safety of the eastern billet they’d been fighting from.

At roughly H+6 minutes Simons directed all elements of Greenleaf to fight their way to the extraction point. With 60 seconds the Support Group Leader (Simons) had a full accounting of his people at the LZ, which had been marked using strobe lights. At this point Element 1 secured the LZ and “placed suppressive fire on the western portion of the compound” where apparently Greenleaf was still taking incoming fire. Element 2 closed off the LZ from the south and at H+9 minutes Simons called for his helo.

“We heard ‘Wildroot’ (Simons’ call sign for the raid) request extraction,” Montrem remembered during his interview with this author. “We needed a flare to guide in on, and after asking for one, both Britton and I saw a strobe light activated almost exactly where we’d originally landed.” On the audio tape made of the raid’s radio transmissions, Simons can be heard asking the flight crew if they “need a map?” to find him once the extraction was called for.

Again, Al Montrem. “We just flew in and picked them up, shuttling them over to Son Tay and dropping them off outside the walls.” After this second combat insertion in less than 10 minutes, Apple 1 headed for its holding area to await recall from Simons. By now Meadows with his Blueboy team had accomplished its assigned tasks inside the POW camp, and “Bud” Sydnor’s Redwine team was successfully handling Greenleaf’s mission upon being so notified to take up the slack as Simons fought his way in to-and out of-the secondary compound.

Sydnor’s people also dropped the bridge over the Son Cong River as a convoy of NVA troops was crossing it to reinforce two of their military installations now under attack. As all of this was taking place, the A-1s were called in and began hitting targets all around the POW camp. This included the small footbridge between the adviser and POW compounds, as well as the secondary camp itself. This mission was called in by Simons himself as Greenleaf was finally being landed at the correct objective.

In conjunction with Dick Meadows’ own airborne assault element and a sortie of A-1s, Simons and his men indeed engaged and killed an impressive number of enemy personnel both in and around the secondary camp. An exact body count would never be possible as there was no one other than the North Vietnamese left to sort through the pieces once the raiders departed. Certainly, the NVA would never release any record of its casualties given the huge loss of face they suffered. Such a body count would have to include all those personnel killed at both camps, as well as those on the roads and manning Son Tay’s air defense systems.

The Raiders carried tomahawks for both close quarters battle and extraction needs. This one belongs to SGM Jake Jakovenko. (photo courtesy Greg Walker)

During an FTX to Puerto Rico in 1977, SGM Jakovenko (left rear) and VN veteran Mike Echanis put on a no-holds barred hand-to-hand demonstration. Jakovenko and Echanis were close friends and both exceptional martial artists. Mike would later describe "Big Jake" as one of the toughest men he'd ever met. (photo courtesy COL (ret) Juan Montes, 5th SFG(A))

Udo Walter

Further, the North Vietnamese never admitted to the presence of foreign advisors, especially the Chinese. To publicly admit a number of such “visitors” had been blown away in the most daring raid of the war would have compromised the North’s policy of “plausible denial” while jeopardizing such personnel being speedily replaced under either clandestine or cover agreements. According to the Captain Udo Walther, Simons’ executive officer for Greenleaf, “It wasn’t a secret that there were Chinese there (at Son Tay), and it wasn’t a secret that there were a bunch of them.” Walther stated he took photographs on the scene of dead Chinese and that he informed his debriefers of their presence during the attack. He does not know where his photos went once the film was turned over.

What Walther did keep was a Chinese officer’s belt buckle he took off a body at the secondary compound. In 1973, teas billionaire H. Ross Perot would fly all those 70 POWs who’d been held at Son Tay to San Francisco for a reunion with the raiders. Walther’s war trophy would be given to Perot “on loan” for display purposes.

“No public statements regarding this operation are permitted even after its completion unless by CTF-77 IAW directives received from higher authority…press and other visits to units involved in this operation are to be discouraged…Upon termination of this operation, this OPORD will be destroyed….”. – Commander-Joint Contingency Task Group, JCS

Thankfully, the above did not occur and the triumphs and lessons learned from Operation IVORY COAST were not lost. True, no U.S. POWs were recovered that night in November, but it was accepted prior to mission launch that reports of their being moved might indeed be correct. “I felt we owed whoever might have been there the effort,” General Don Blackburn has recounted for the record. “I knew we could get in without being detected (courtesy of CCN’s unauthorized, unreported ground recon of the area 72 hours prior). I believe there would be no casualties on our side because of the level of training and the caliber of men involved. Plus, there was the additional impact of letting the North Vietnamese know we could mount such an operation. Until then, it had been their pattern to do whatever they please inside South Vietnam while we just stood by.”

At 23.18 hours on a dark night in November 1970, that all changed.

* 09/14/22 Correction — Warner A. Britton was incorrectly named Walter Britton in this article in the original posting of this story. An editorial decision had been made to leave the story in it original form. John Gargus, one of several mission planners and a participant in the raid, sent several clarifications/corrections sent to our editor and the writer. The post with that information is linked at the beginning of this article and can be found here also.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR — An author and Special Forces historian, Greg Walker served with the 10th, 7th, and 19th Special Forces Groups (ABN). He retired in 2005. He is a Life member of the Special Operations and Special Forces Associations.

Today, Mr. Walker lives and writes from his home in Sisters, Oregon, along with his service pup, Tommy.

That would be Col. Warner Britton, PIC of Apple One. Not Walter Britton. You’re welcome.

Thanks for your comment, and for your attention to detail. Yes, we’d been informed of this error and it was referenced in the article linked at the beginning of this post. An editorial decision had been made to post this story as it had been reported to the author. However, Col Britton’s name has now been corrected in this post to avoid further confusion.

Cherry 1 is on display at Cannon AFB New Mexico

Does anyone know what happened to Cherry 2?

That’s a good question. I’ve sent a message out to John Gargus. We’ll see if he knows.

This from Col (ret.) John Gargus: Cherry Two, aircraft # 64-0558 was the second Combat Talon that was lost with its entire twelve man proficiency training crew. It happened on 5 December 1972 in a mid-air collision with an F-102A from the South Carolina Air National Guard during an intercept training maneuver over Conway, SC. Sorry about the sad news.

The effect of the accident on Horry County, over which the crash took place, was such that 50 years later they memorialized the men lost: https://www.pjstar.com/story/news/columns/luciano/2020/12/03/luciano-five-decades-after-fiery-crash-fallen-airman-honored/3785500001/

Were there diversion raids apart of the overall plan? Given a mission from 525 MI , my team with Vietnamese were directed to hit a North Vietnamese VC supply area in Cambodia. I went to the SF Museum and the curator asked BG Minor who said if it was planned the CIA did it. FOIA request to the CIA was returned with extraneous information basically a non answer. Wonder if there was any relationship between the timing of our action and the Son Tay raid.

From John Gargus:

The Son Tay raid was a very unique surgical operation commanded by the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The raiding force was inserted into the war zone in secret and the operation to free the prisoners had absolutely no relation to the daily conduct of the war. Consequently, all operations on the morning of the raid were a part of daily operations against North Vietnam – as if the raid had never taken place. The only supporting unit for the raid that did not train for it and did its own planning for the event was the US Navy which executed a diversion over the Port of Haiphong. The CIA had absolutely nothing to do with the raid. It simply served as a source of information on the prison. They had no information about the relocation of the POWs. until after the raid. The only official raid participants were people trained in Florida and on orders to the Joint Contingency Task Group, Navy task force participants in the diversion and all other supporters who were on orders just for that night’s flight. The first light attacks that morning were previously planned attacks under Operation Freedom Bait that had nothing to do with the raid.

SOG was Studies and Observation Group, not Special Operations Group.

That is correct.