The John Nesbitt Story:

The First

Afro-Native American

MAC-V Recondo Advisor

— Part II

By John Nesbitt

All photos courtesy of John Nesbitt

Viet Nam: An account of the experiences of Sgt. John E. Nesbitt, 16-844-233,

Detachment B-52 Delta Project

From September 18 through December 1966 and

from December 1967 through May 1968

at the MAC-V RECONDO School,

RECONDO STUDENT # 114,

RECONDO ADVISOR #135

From June through October 1968 at

Detachment A-401 DON PHUC, Mekong Delta,

CIDG Company 43, 44 and 46 MIKE FORCE

Editors Note: Part I of John Nesbitt’s account of his Viet Nam experiences appeared in the July, 2023 Sentinel.

The Australians

If I recall correctly, I was introduced to Msg. Cowan of the Australian Special Forces. A very special operation was in store — another water infiltration — in an area north of Hai Phong, at last light. Once in the bush, we wait and listen.

Night began to come, EENT [Ending Evening Nautical Twilight], with a final review of our direction, and we are off to the target area with the CHU HOI, NVA at second man, myself third, and other Aussies behind me. We follow a cow path to the target area; now the asset takes over and leads to a hooch with radio antennas. It is some kind of communications command post. My heart is closing in on my mouth; I can feel the sweat starting to drip; my palms are wet too. Suddenly, the asset stops and signals by hand the actual target location. The Australians move forward to prep the site, meaning to assure entrance and exit from the building.

Now, I’m up and moving with the asset into the building. I am as quiet as a mouse, weapon ready. An officer comes out from nowhere! Maybe a restroom? I only hear the crack of a burst of three rounds as the unfortunate fellow dropped like a stone; even the automatic weapons were silenced. As I enter the room, two individuals in Chinese-looking uniforms began to stand. Automatically, I place two rounds in their heads, backed up by Cowan, the team leader.

Then it’s out the door back into the night, and follow the asset to a stream, follow the stream to a small bridge which we must traverse, and continue to the shoreline. There is a farmer(?) or some late travelers; they are as astounded as we are. I looked away for a split second, and the Aussie’s dropped them immediately. We wait in hiding till first light; having sent a SITREP, the choppers will be here soon.

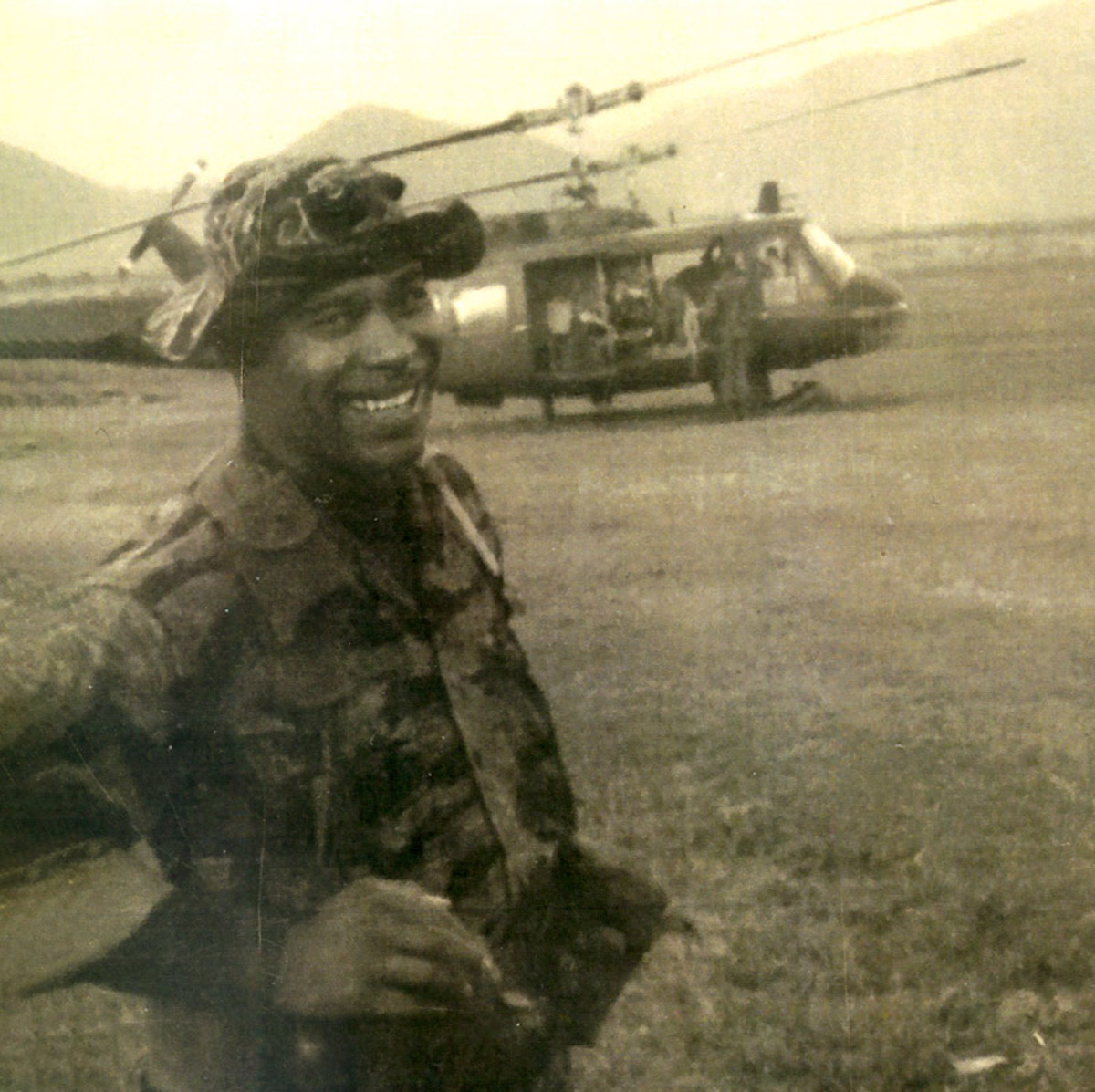

Aussie team preparation

No incidents getting out, I took a picture of the team while waiting. I think a picture of me was taken. Yes, I sneak a camera everywhere.

On the chopper two miles out to sea, I have time to reflect on the two men sitting at the table. In my mind’s eye, I can see them clearly, like the one who stumbled onto my foot last month. They were Chinese, not NVA. The morning began warm and cool, and the ride back was long. I had not shot people like this before. Fuck it, better them than me. We were debriefed by joint army, CIVILIAN personnel, turned in our hand weapons, and ate a big meal. We landed back in Nha Trang that night on a Chinook chopper. At the team house, BEN was sitting around telling nigger jokes. I drew my 357 and raised it to the ceiling, released a round and screamed, “As you were.”

Eye contact became very scarce with the other occupants, and a senior NCO MSG Smith started to act his rank. As I left the team house bar, I screamed to him, “NOT NOW.” He got the message and left me alone. I smoked a joint and began to cry.

Note: Because of the incident with Lt. Nuk at the debauched Reaction Force near Phu Bai, I heard I might get court-martialed if the Vietnamese command felt it was 2nd degree murder. It was a good thing my A.I.T. friend Roland Dosier at SF headquarters told me about ROTC as a safety net. I applied, and if accepted, I would be out of the country in 45 days; a court marshal would take 60 in this case. Well, I got orders to go to ARTILLERY OCS, that means I’m out of this country before Christmas, 1966.

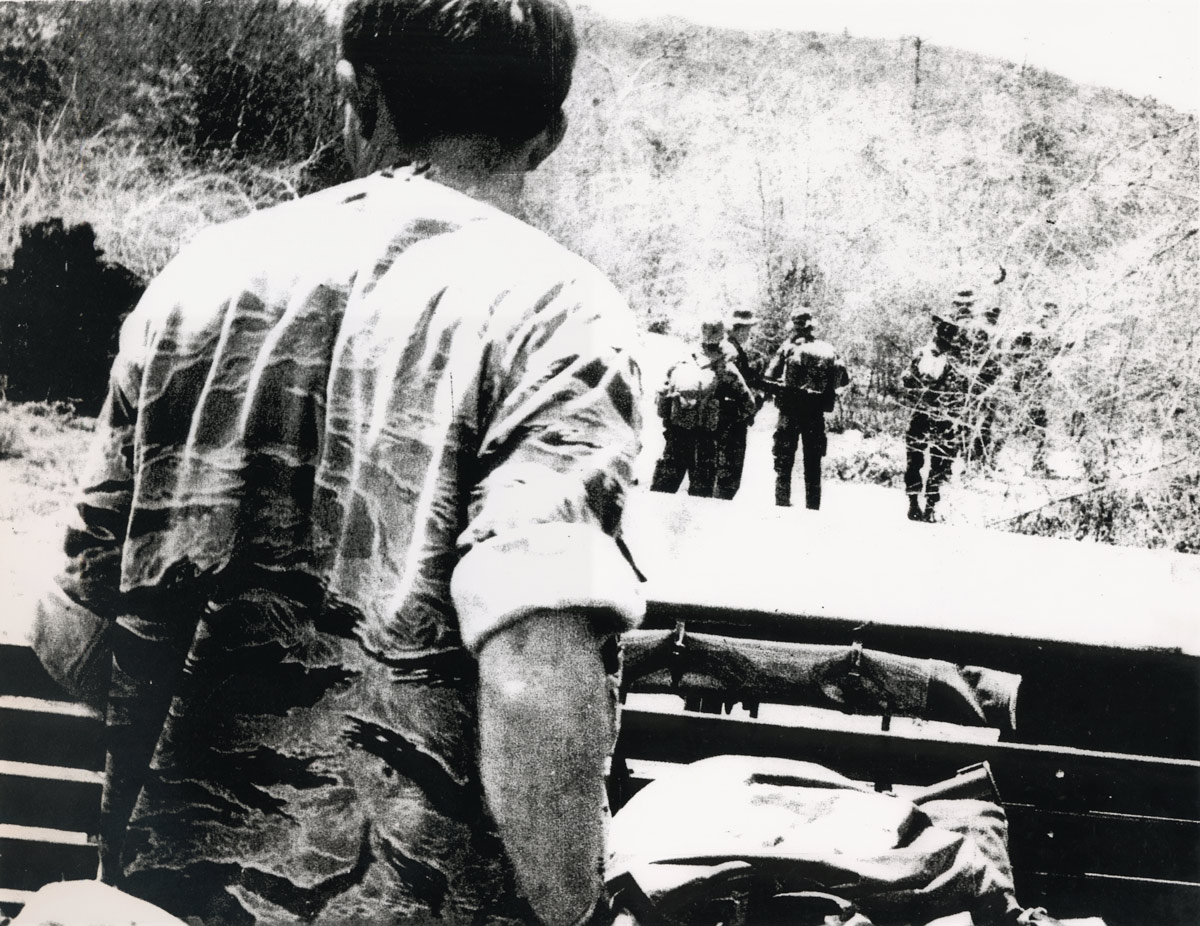

Team mission review: Australian team, air infiltration

I had been set back in OCS for the third time because of my inability to grasp logarithms, and I was waiting to be dropped out of my class. The day I was to go resign I saw a black CID car pull up.

“CANDIDATE Nesbitt!” The first Sgt. Called, “Report to the Commander’s Office!”

I fantasized about an escape to the Wichita Mountains; I was going to get court marshaled anyway! Too late; they got me for murder in a war! I entered the room, and there were two plain-clothed gentlemen, one uniformed provost officer, and the commander of the Artillery OCS.

“Sit down, candidate, relax.” “I think you know what this is about,” stated the older CID agent. “The Army has dismissed the initial inquiry as to the possible charges that were alleged against you for the death of Lt. Nuk. It seems his family was of Chinese extraction, and it is known that the family was active and sympathetic to the Viet Minh. We also suspect that the ambush you were in was perpetrated by the family since Lt. Nuk was an LLDB [Luc Long Duc Biet, the Vietnamese Special Forces]. You don’t have to worry any longer.”

I was out of there like the sonic boom of a sound barrier wave. I went to see Lore in Indiana in my ‘55 Chevy.

My return to Vietnam was perpetuated by a phone call to Mrs. Alexander at the Pentagon. She assured me of my orders over the phone in November 1967. I’d graduated Operations and Intelligence training while in the 3rd SFG, at the J.F.K. Special Warfare Center, Fort Bragg, N.C., with a new Military Occupational Specialty [MOS], 11F4S, later translated as 96B10, intelligence analyst.

My best friend Michael Joseph and I completed intelligence school, ranked 1 and 2. Mike Jo and Johnny Anderson were weightlifters. Little did I know then that I would serve in the Mekong Delta with Johnny a year later.

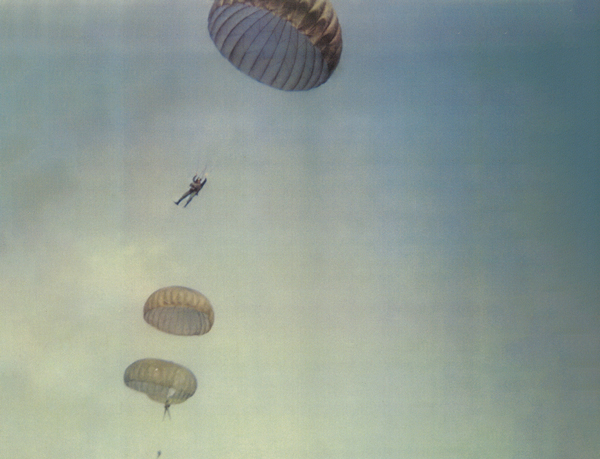

Because the 3rd SF group had no real slot for me, I wasted my time a lot, and almost got two article 15s in the meantime. I racked up 18 parachute jumps, so back to the “jolly green training aide” Vietnam. Mike Jo and I were to travel to Vietnam on the same orders. He got into a fight at Fort Lewis the day before we were to meet up and ship out, and while challenging some legs, he ripped his thumb nearly off. He would have surgery and heal for two months before arriving in country.

MOS Training, Ft, Bragg, NC, March 1967–December 1967: Jump Day at 3rd SFG

RS5 — December 23, 1967

I began Recondo School mission 5 for me, Team Leader SSG. Mrsich, Asst. Team Leader Sgt. Nesbitt: Air infiltration, beyond Khe San near the Laotian border, the Americal Division LRP team, our mission, seek information on the Ho Chi Minh Trail activity.

Once again, at first light, we are in the brush and listening. SSG Mrsich is acting crazy! He stood and walked through trails and brush, inviting shooting from the VC. He even stood up to pee one morning, which would give us away without knowing. At night, he acted as if he were hallucinating; he was standing and readying his weapon at one point until I pulled him down.

Day four, we see a few cache suppliers, females; we made no contact but wonder why everything is so quiet, with minimal movement along the trail. An increase of medical supplies seemed to be trickling in. On New Year’s Eve, we get a message to return to Nha Trang. “Wow, a day early,” I thought. Upon arriving back at Nha Trang Air Base, we found ourselves in a firefight. The TET Offensive had begun. The asshole Mrsich jumped out of the chopper, firing his weapon like a madman. We are on a helipad (!) with other Americans and friendlies around us; he is like John Wayne until a mortar lands next to him and sends him flying. The idiot lived and went home. I make my way to the Recondo compound and set up at our perimeter.

The turkey shoot began at 11:30 AM that morning, and we were being re-supplied with ammo at five o’clock that evening. Reports of action in town and all around us made me feel safer in the bush. 81 mortars, automatic fire, and probing fire continued throughout the night. We could risk an hour or two of sleep in the bunkers, but once in a while we could hear the screams and charges of the VC /NVA or whomever they had recruited to fight.

Air strikes were the morning show for us, “spooky the magic dragon” was our show at night. We could see body removal going on in some areas, so we called in chopper gunships on them. I drink water like it’s going out of style while in combat. The next two days were like being a grunt; it was all about perimeter security to prevent saper breach.

As the local fighting carried on, another mission order was issued. I was to go into the Nha Trang Valley with SSG Gudgell and a team to call forward fire missions against the VC coming in through the valley. Team Leader SSG Gudgell, Asst. Team Leader Sgt. Nesbitt, two other new SF instructors, Kelly Hughs and Kim Fletcher, and three members of the 24th Infantry Division, infiltrated by air. I carried a serious bad feeling.

Once on the ground, we saw them first! After our 30-second wait and listen, we followed to see where they stopped, logged the location of a cache spot, and called in artillery. There is enough to supply a battalion, and as the rounds fired for effect, we moved quickly through the jungle looking for other spots to pick, except in our haste we were detected and were now being tracked.

Gudgell was the team leader and had more experience than I, so he called the shots. RULE one! Never split your team. Gudgell directed me to take the three 24th Infantry people and move to the bottom of a hill while he called the new Cobra gunships in. Well, the asshole threw a color grenade that rolled down the hill 25 feet from our position.

For ten minutes, Cobra helicopters strafed the hill where I was with the three others. I tried to get as small as possible as the tops of the trees rained pulp down on us. The crack of 3,000 rounds per minute from the Cobras’ machine guns within inches of me now made me want to scream, but with tight eyes and body position, I could only remain frozen while the shooting lasted. When the choppers left, I called out to the 24th Division guys. One was crying, the other lay peppered and shredded with holes. Pieces of rock, tree bark, and dirt stuck to my skin. I tried my radio but it was damaged. Now I’m stuck with a body, no communication, and nightfall approaching.

The VC returned after the choppers to check the area. It was a Swedish airlines that picked up my UHF distress call and passed my code Diamond from “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds” to MACV then to the SFOB. Soon the choppers came in. Someone had to crawl out onto the LZ on his back and open a FLORESCENT panel to identify the spot for the choppers to pick us up. So, there I go again. As rounds popped around me, everything turned slow motion, and I could hear my breath inside me.

I lay on my back with the panel over my chest. The 24th Infantry guys carried their buddy to the chopper while I now provided cover fire. My aim was true; the few figures fell like carnival Ducks. On the ride back, I realized I fired from the hip without taking aim, a distance of 35–40 yards. My eye is now synchronized with the muzzle of my rifle — it means my eye knows the trajectory of the bullet’s flight.

When I returned to the Recondo compound, I was questioned about splitting the team. The white boys want to blame the split on me because they thought Gudgell wouldn’t have BECOME SEPARATED. Once again, I had to tell them to “fuck off, and Gudgell, like them, ain’t shit.” If anyone had a problem with that, let’s settle here and now with my rifle, and if I hear another nigger word again, I will begin shooting. When Gudgell got back, he gave a “theory” he had for his actions and half-assed apologized for the near disaster. I told him to fuck off too. My attitude became worse.

March 1968, SGT Michael Joseph showed up early from the States. We spent a night in a bunker smoking weed and talking about where to be assigned. I begged him to stay in Nha Trang! Be my assistant team leader, get Recondo qualified, he would get his own team, it was better than the mobile guerrilla force being formed from the MIKE force. As morning came, we agreed to let the soul take to the wind; that’s the cleanest fate you can have. He was assigned to the mailroom at C. Co. Da Nang.

RS 7&8 — March 1968

RS 7 and 8 went off without casualties and without incident. I remember training Marines and Koreans; time by now is layered together. One day or night is the same as a week; nothing special sticks out in my mind during that time.

It was March 15th when I really began to enjoy Rum and Coke. As I sat at the bar in the SFOB, a guy came up to me and said, “Hey NEZ didn’t your friend Mike go to Dan Nang?”

“Yeah, what do you hear?” I said.

“The teletype has the name of a Michael Joseph, KIA today.”

We walked to the S2 office, drinking and talking about the day. “Here man, look!” There it was: Joseph Michael A. KIA, 2:34 p.m. I sat there and cried, drank more, and cursed the fact he was so hardheaded. I wrote a letter to his family; it got there before the Army sent the announcement. I felt my luck running out, and I didn’t even care anymore; I had nothing to begin with. So, when will I die?

RS 9

At Quin Nhon below Da Nang, we lost three choppers, and four of seven team members, we were extracted by rope ladder. I was given a wrong fix for my location by SSG Petz, one of the flunkies of the crew of Recondo Instructors. I had to take him “behind the barn.” As a result, my name came up on the rotation list more often. I resisted depression and cloaked my anger.

April Fools Day! RS 10

At the Cambodian Border, Team Leader Sgt. Nesbitt, Asst. Team Leader Sgt. Shamblen, and Kim Fletcher from California, they were medics and ‘new school’ intellectually above the traditional SF Sergeant with years of experience; they were my age, 21 and 23. The Ho Chi Minh Trail now was critical to the NVA because TET had kicked their asses so bad. Women were now the main force behind supplies being stashed, while VC and NVA men and boys coordinated attacks.

While eating our MREs’ on day four, a patrol walked upon us. I heard them and hoped they would pass, but they saw us and responded immediately. In an instant, two of my team were down, and we were running like hell to separate distance. Down a 65-degree gulch, we fell, laid there for twenty seconds, and emptied our weapons into the trailing VC. I radioed for extraction; two choppers were ready; three were already in the air: one command ship and two gunners. The extraction choppers were first to arrive, but they waited for the cover choppers while we cat and mouse played sniper between the LZ and the E&E route. I lost one other team member somehow. At the LZ, there were only me and two others. As we headed for the chopper to get on, I backed up to be the last one on, providing cover fire…

Fletcher and Shamblin made it on, but the chopper was hit, and I didn’t get on because of the weight. I ran to the tree line, thinking the other choppers would come.

There were no other choppers; I threw a couple of grenades with a smoke and hauled ass out of the area. The false smoke made them think I had marked the LZ, so they stayed and waited for choppers that were not coming. All night, I could hear voices. I thought at one point they had dogs! I headed south by southeast towards the central mountains. I ate a Bennie (speed) from my medical pack. Man, I was keen and could hear everything within a mile — birds, ants, crickets, and my own heartbeat. My fear was overpowering because American Special Forces are automatically killed by the VC or taken to North Vietnam by the NVA. At sunlight, I tried my UHF radio and picked up an Air Force fuel tanker near Thailand.

I gave my fix to the pilot, who alerted MACV, who relayed the message to II Corps command, who dispersed a chopper to get me. I heard squelch signals from the Air Force jet in the area. I got ready to meet my pickup at an LZ. I wanted a death challenge, my body resisted acting appropriately. I was going through the motions, but I was numb about my life or safety. Nothing connected anymore; the colored smoke, the extraction, and the debriefing was a blur. I slept for two days. My luck is gone, I told myself, now I’m waiting to be killed.

As I sat in a bunker the next night, waiting for Charlie to probe the perimeter, Ben came in. Ben was a Master Sergeant and a bigot; his first words were, “It’s so dark in here, you should feel at home,” and “Where are you? That’s you, Nesbitt?” Before I could think, my Kbar knife was at his throat. I don’t know what I said, but I wanted to kill this American. The sound of others coming into the bunker made me retreat from his body.

We never spoke about the incident — another thing I swallowed — without being able to talk to someone. Things got worse. I had written my dad and briefly mentioned the prejudice I was experiencing. He in turn wrote New York Senator Robert Kennedy and my commander, Major Lundy. After a short lecture, MAJ Lundy asked me where in the country I wanted to go, OUT of Recondo. I hadn’t heard of any action in the Mekong Delta, I chose D company.

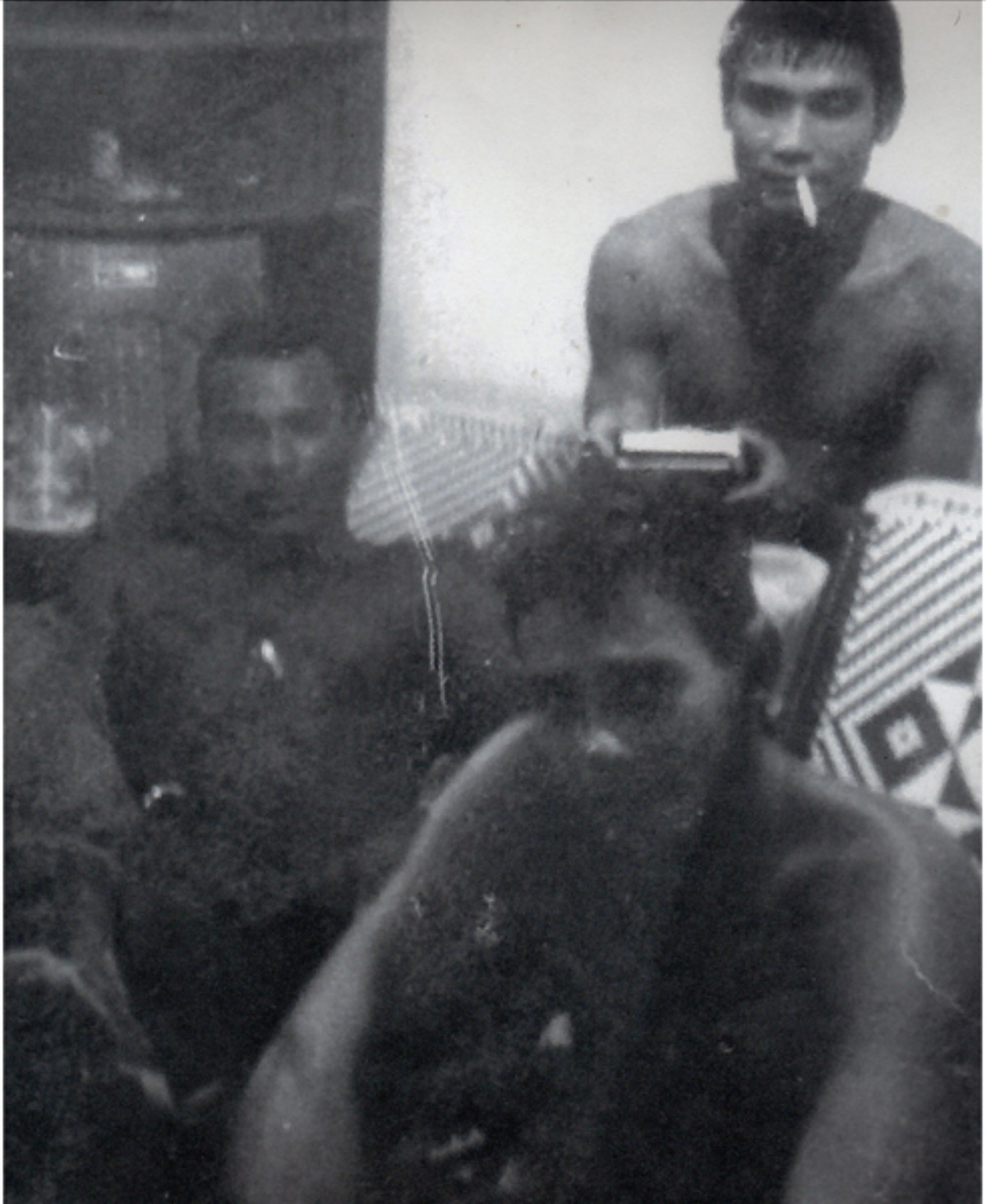

At left, John Nesbitt, center front Johnny Anderson, and Cowboy (Body Guard), June-October 1968 Mekong Delta.

Mekong Delta, June 1968

I was assigned to Detachment A-401 at Don Phuc, 300 yards from Cambodia. As a recon person, I acted as an infantry cadre for the indigenous MIKE Force, 44, 45, and 46 company of Vietnamese, Cambodian, Montagnard, Hmong, and Chu Hoi reassigned. At this time, the psychological stress from Recondo affected my sleep and relationships.

I was not satisfied unless there was a problem to be solved or anticipating shooting, I kept my .357 close at all times. I had 5 months to go — still too long to relax — so I got into the idea of body count and search and destroy. It was simpler than Recon and less technical in the mission objectives. BODY COUNT!! As Don Blue recalls, I showed up at a time when ammunition was almost gone. I arrived with the ammo resupply.

My memory is now a blur, other than day-to-day survival and night stealth by the Viet Cong. Patrols into Cambodia were the norm as the final miles of the Ho Chi Minh Trail splintered into the Delta in all directions and waterways. Isolation became my solitude. Little did

I know I had got myself deeper into trouble by coming here. In ‘66 we shot six of seven days per week at someone, or someone shot at me. I was going to go to Nui Coto Mountain soon.

July 12, 1968

The first assault on Nui Coto Mountain, the largest of the Seven Sisters mountain range in lV Corps. After three days of expecting snipers but getting nothing, it was quiet. The booby traps were our enemy. As everywhere we expected, a booby trap off-trail movement became the norm. Our accountability was for 300 men, 275 Mike Force, four A detachment companies, and 15 Americans. At 2:00 PM, a rainstorm began. A stream was now a small gorge, and the shooting began just like the rain. I squeezed my eyes shut as B-40 Rockets made a circle around our position by the creek. I slithered down, trying to understand our situation: this is not Recondo; you stay and shoot! Automatic fire was like the sound of the rain.

Screaming, crying, yelling started, and I realized I must face this or be dead. I moved and fired until the M16 jammed. As I grabbed for a B.A.R. from my radio man, two rounds smashed the rock between us, cutting both our faces. We looked at each other with emptiness and wide eyed.

For three hours, the V.C. and NVA showered our position. Donald Blue, a medic, was to my left when Lt. Thurston got hit; a round severed his femoral artery. He yelled for Blue, but I was closer. I didn’t move. Blue slid across the ground to Thurston’s side; the artery was cut, and a tourniquet was needed.

Don Blue, at left, with John Nesbitt to his right prior to the assault on Nui Coto Mountain. Don Blue, now a retired Command Sergeant Major, saved Lt. Thurston when he was shot through the left femoral artery during an ambush initiated by the Viet Kong.

We had to wait for the other company to descend from the mountain before we could retreat out of the dead zone. We were experiencing plunging fire and direct fire; the pace was frantic, as I thought I saw a brown uniform run past me. I went to assist Blue. We carried Lt. Thurston in a fireman’s carry for a third of a mile through the wooded area, which led to the rice paddies. My pack was still on the ground back at the water hole; all I had was my rifle and later an AK which had fallen from the hand of an NVA. I ran with Blue about a quarter mile out into the paddies!

As we reached the staging area, carnage was the scene; about twenty-five men were lined along the rice paddy wall, wounded or dead and dying. My stomach flipped, and I went into a daze. Don Blue let Lt. Thurston off to be medivaced and waited for the surviving remains of the companies. Our interpreter, Cowboy, shot and killed a prisoner. We drank the blood from the liver and heart — now I’m really crazy. That evening I went to pee, and my penis had a leach on it; the foreskin was scarred when I pulled the leach off.

The next morning, I went to pee, my penis was the size of my fist. I almost fainted. I had left the leech head in the foreskin, and now I was infected. We got the rest of the 125 remaining MIKE Force back to Don Phuc. We assisted as many MIKE Force as possible; 23 were killed that afternoon, July 15th, my birthday. Blue went home soon after, only to return within a year.

I was medivaced to Can Tho, where I was circumcised at the age of 22, a wounded dick and twelve weeks to go home. I was also wounded in the right knee, but the bullet went around and under my skin. I cut the round out myself near the location where we left Lt. Thurston.

My ETS (Ended Time in Service)

17 October 1968, 4:00 a.m., Ft. Lewis, Seattle, WA

SYMPTOMS after military retirement:

- Interrupted sleep,

- Delayed sexual response when nervous

- Self guilt for being alive,

- Agent Orange blisters on feet when temperature is over 90°.

- Self destructive behavior or attitude when approaching occupational success

- Drug and alcohol usage, abuse relapse and recovery, presently stabilized

- A need for a higher spiritual experience than this dogma society

- Willingness to kill another person, extreme impatience at times.

- A need to be isolated

- A need to cry when good news happens and no response for bad news.

- A feeling of extreme compassion inside when reflecting specific death events.

That’s it in a nutshell.

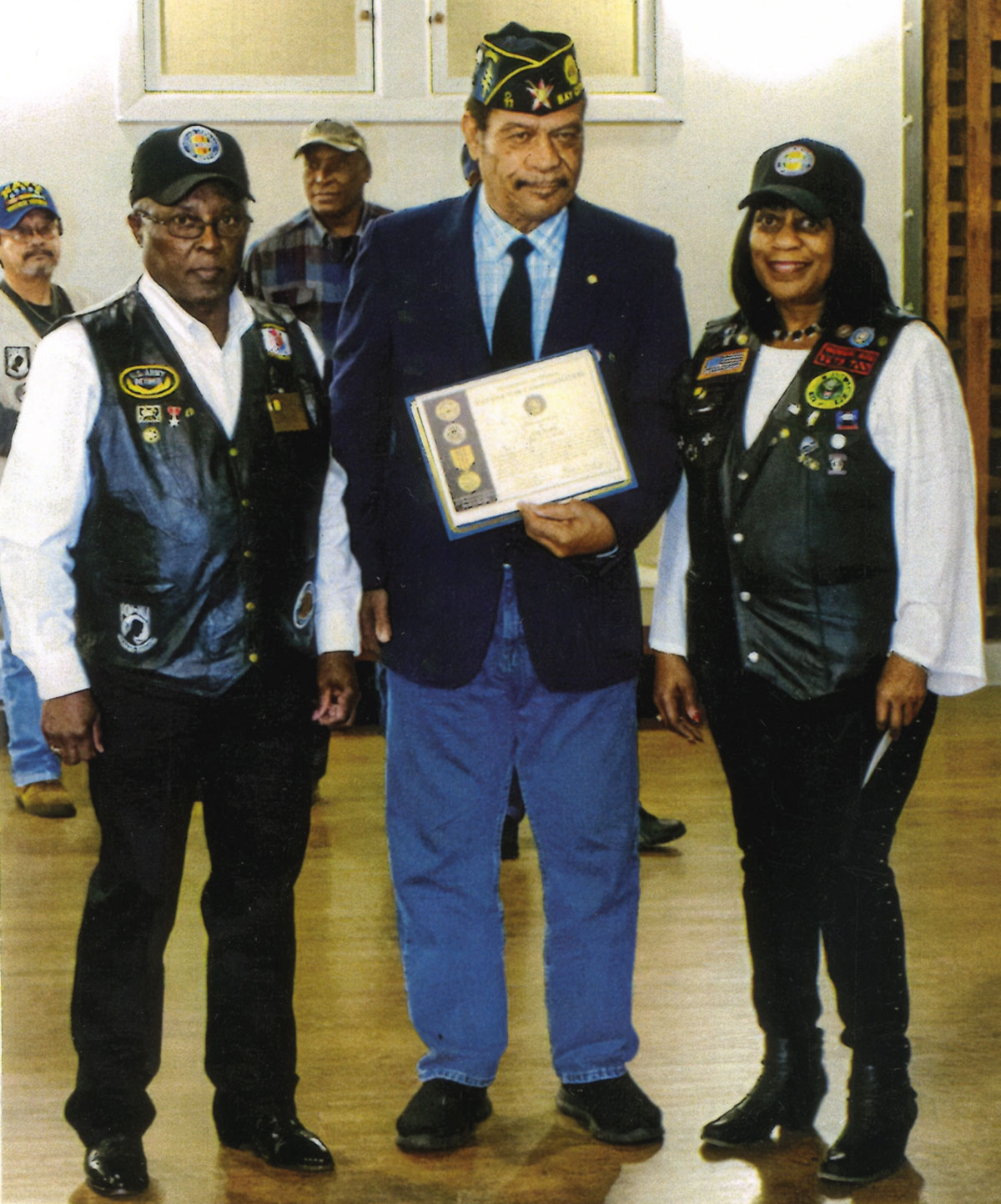

John Nesbitt with representatives of the US Soldiers Association — to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Tet Offensive, John Nesbitt received both a bronze star for valor and the air medal. (Courtesy John Nesbitt)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

John Nesbitt enlisted in the U.S. Army in January of 1966 and was deployed to Vietnam on August 18, 1966. He was recruited by the Special Forces and sent to Project Delta for reconnaissance training. He completed two assignments with the unit: September 1966–December 1966 and December 1967–May 1968. He became the first African-American advisor for the MAC-V Recondo School, where John completed 14 missions. Subsequently serving with Detachment A-401 in the Mekong Delta with the “Don Phuc Mike Force,” he went home in October 1968.

Upon discharge, John continued his education, earning a BS in Secondary Art Education and a Master in Fine Arts (MFA). He taught at several schools, including Grant Union High School and Hampton Institute, College of Arts and Letters, in Hampton, Virginia. As a Case Manager for the Mather Community Campus in Sacramento, John initiated a Resident Council and Community Garden.

John’s commitment to community service work has been demonstrated by his full involvement with the Retired Senior Volunteer Program (RSVP), the Neighborhood Emergency Training (NET), and the Veterans History Project (VHP). His contributions to these groups led to his selection by the Bank of America as one of five “Local Heroes” in his community. He also received Congressional recognition as a Sacramento Regional Community Trainer.

John is also a fine artist whose oil paintings have been displayed at various galleries throughout the US. He is also a Tae Kwon Do master with 7th Dan certification and has operated a training school that offered special youth programs.

John Nesbitt has raised two children and is currently living in the Sacramento area.

John Nesbitt’s VHP interview about his military service can be viewed at https://www.loc.gov/item/afc2001001.38179/#item-service_history

To learn more about John Nesbitt visit his website at https://www.jnesbittandassociates.com/index.html

Hi John,

My name is David Biron, I was a good friend of Michael Joseph. We went through training group 12B, back in 66. Later we were assigned to 3rd Gp.. Point is, I was in country when Michael arrived to his assigned B-Team in DaNang. I was located at FOB2, part of CCN. I got to say hello to him for a few minutes. Later on, for a designated mission I arrived at his “A” detachment camp with my HF, and found out he was KIA the day before, returning to camp in a convoy. I certainly remember you as well. I believe Michael’s cousin returned home with his body in California.

I always remember and honor Michael, along with others I have lost. Thank you for your story and your service.

Alfred Smith Aug 1st 2023 5.11 pm

Alway glad to hear of a fellow trooper from B-52. I was assigned to SF 5th Gp in 65 aviation. July Charlie Beckwith took over I was at a Loa when he was wounded. Then on to A Shau, . Then I left after A Shau fell, welcome back