Burying the Dead with Dishonor Part II

SSG (ret) Timothy Hodge (author collection)

Editors Note: Be sure to read “Burying the Dead with Dishonor, Part I” if you haven’t done so already.

By Greg Walker

The White House

August 5, 1987Dear Sergeant Hodge:

Nancy and I are thankful that you are in good hands and on the mend. All of us—your family, friends, colleagues in uniform, and Americans everywhere—are praying for your speedy recovery.

When you went to El Salvador to take on this difficult and dangerous assignment, you carried with you the hopes of your fellow citizens. You carried as well the aspirations of the people of Central America for a future of peace and freedom. As Commander in Chief, I want you to know how proud I am of the fidelity and courage with which you did your job.You must feel especially keenly the deaths of the other [service] members…we are mindful of their sacrifice, and we recognize the grief that is yours at their loss. We will never forget them, and we thank God that we have men like them and like you whose willingness to serve makes all of our liberties possible.

May God bless you and grant you health and strength in the days ahead.

Sincerely,

Ronald Reagan

SSG (ret) Timothy Hodge

United States Army Special ForcesJuly 21, 2023

“With great respect—reading through this, memories and recollections, really brings home the gravity of the situation I was in. For several years, I never knew anything about the chopper going down and the loss of lives that were in my behalf. When I was told about the chopper going down and everybody dying, I was told the reason for the delay in my knowledge was so that I would not take on the burden of knowledge that they sacrificed their lives for mine. I don’t know if it was a fair trade, but I have had 36 years now—36 years and six days. I don’t know what to think.

“Please pass my heartfelt gratitude on to everyone who has written narratives of memories and descriptions. People asked me if I ever went and saw any of my old friends from Group…No, they need to know that they are invincible. We all knew we could die. No one, absolutely no one told me I might live.”

That others may live

The mission of the U.S. Helicopter Detachment in El Salvador during the war was to provide support to the U.S. Military Group (MilGrp) and U.S. Embassy. Priorities of flights were determined by the U.S. Military Group Operations staff. Missions included day and night extractions of U.S. military advisers from various remote or urban locations and MEDEVAC assistance to U.S. personnel. Pilots were required to be mountain qualified, night vision goggle certified and up-to-date, and deck (naval vessel) qualified.

On July 15, 1987, the Helicopter Detachment standby crew, pilot in command CW2 John D. Raybon, copilot 1LT Gregory Paredes, and crew chief SP4 Douglas Adams, received notification for a MEDEVAC mission from MilGrp Operations. The crew was directed to fly to the Salvadoran training base (CEMFA) at La Union to transport SSG Timothy Hodge, a Special Forces combat adviser, who had been wounded that evening. Chief Raybon was to fly first to the landing zone at the 1st Brigade Headquarters in San Salvador. There he was to pick up two Special Forces medics and two senior U.S. military officers and then to proceed to CEMFA, roughly 75 nautical miles to the east. After departing the Salvadoran air base at Illopango, the crew were given a mission change. They were now to proceed to San Miguel as a Salvadoran MEDEVAC helo and crew were enroute to CEMFA, just 16 minutes from the military hospital at San Miguel. Once there, Chief Raybon was to stand by for further instructions.

Raybon’s helo departed Illopango under night vision goggles at 2235 Hours, arriving at the Brigade helipad at 2245H. Picking up the four passengers, Raybon lifted off within minutes and headed toward CEMFA. Within a minute’s time, Chief Raybon was redirected to San Miguel. Eight minutes later, at 2255H, MilGrp Operations was advised by Mr. Raybon that they were encountering thunderstorms and were returning to Illopango. At 2256H, Detachment Operations attempted contact with the UH-IH but received no response. Repeated attempts to contact Mr. Raybon failed and the Detachment OIC began calling the tower at Illopango. Also called were U.S. personnel at San Miguel and CEMFA, as well as other locations along the flight path. All attempts to locate the aircraft failed. Detachment Operations then launched additional U.S. helicopter support from Illopango in an effort to locate the missing aircraft.

On July 16, 1987, at 0255H, Detachment Operations was informed that local civilians living near Lake Illopango had discovered the aircraft, confirming it had indeed crashed. At 0305, due to ongoing combat operations elsewhere in the country and an earlier firefight between guerrillas and base security at Illopango, a UH-1 began transporting additional U.S. military advisers, security personnel, and medical personnel to the accident site. One survivor was located and transported down a steep incline to a MEDEVAC aircraft. He was taken to the military hospital in San Salvador and arrived at 0615H. The other U.S. personnel onboard were determined to be deceased and were lifted out of the crash site by helicopter. They would soon afterward be transported to Gorgas Army Hospital’s morgue in the Republic of Panama for positive identification and autopsy.

Their deaths would mark the highest number of U.S. military/para-military casualties as a direct result of the war in El Salvador since U.S. military operations began in that country in 1981. All total, in 1987, eight Americans were killed in either direct combat with FMLN guerrilla forces or in aviation crashes flown in support of either extraction or MEDEVAC missions.

Back in the United States, Congress wanted to know what was truly happening in El Salvador.

CEMFA – A modern day Fort Apache

Established in 1984, the military training center at La Union, CEMFA, was a magnet for guerrilla forces in the area. Two Special Forces operational detachments, ODAs 2 and 13, were deployed to La Union from the 3/7th Special Forces Group then stationed in Panama. Almost immediately CEMFA began seeing surveillance activities mounted by the guerrillas, and the first troops in contact (TIC) action between U.S. advisers and their Salvadoran troops resulted in valor awards being authorized (in 1997) for SFC Hubert Jackson and SSG Robert Coughman, both from ODA 13.

In 1985, the base was overrun in a nighttime attack by an estimated force of 300 guerrillas. Over 40 Salvadoran soldiers were killed during the battle. The Special Forces team then stationed at CEMFA and commanded by Captain Danny Eagan managed to rally the troops under their command and repulse the attackers. In 1997, all those “Green Berets” involved in the desperate fight that night were awarded Bronze Stars with Valor devices for their actions under fire.

In the aftermath of their nearly successful attack the FMLN released a statement claiming the primary objective of the assault was to capture or kill the U.S. combat advisers at CEMFA. From that point on guerrilla actions focused on the training base and its surrounding ranges, some upwards of 5 kilometers from the base itself, required the Americans to be on constant alert as well as fully armed.

“I arrived at CEMFA July 5 or 6 July 1987, I believe,” recalls Tim Hodge today. “One of the first things we did was familiarize ourselves with the base and the perimeter. I remember making a recommendation for a limiting framework to be set up for the .50 caliber machine guns on the towers. There was great concern of a minimum of 10% of the Salvadorans on the base being insurgents or sleepers. I remember being given the number of 3500 soldiers and personnel on the base at any one given time. It would’ve been too easy for them to sweep across the inside of the compound with the 50 caliber machine guns positioned as they originally were. The Salvadoran soldiers were armed at all times.

“We alternated nights sleeping and pulling guard duty between the team house and a strong point close by. Occasionally there was the sound of gunfire, and rocket-propelled grenades, or RPG 7s, directed into the base. I never went anywhere unarmed. I would be armed with my 1911-A1 side arm and my CAR-15. At night, during my shift for guard duty at the team house or at the strong point, I would carry a 12 gauge shotgun with 100 rounds in a dump pouch, my CAR-15 with 6, 30-round magazines in ammo pouches, two 180-round bandoliers in a butt pack, and 3 canteen covers. Two of these were filled with water and the third contained five grenades. Hanging on the wall next to my bed was my M-79 grenade launcher with 6 flares in a carrying bag .We anticipated an attack, as we were advised by our Intel people could occur at any time.”

Indeed, per the detachment’s team sergeant, a Vietnam veteran, individual weapons, in specific the CAR-15s, were always within arm’s reach. They were kept ready with a live magazine inserted, no round in the chamber, safety off.

SSG Tim Hodge

Special Forces Communications Sergeant

“On July 15, 1987, I was in the team house, in the medics’ room. The medics room and the rest of the team house was in a masonry structure with steel doors. All of this was inside a reconfigured cotton warehouse on CEMFA. It was late in the evening; I have no memory of the clock time. I was in the room with my back to the refrigerator. I was standing and facing the opposite wall where the air conditioner was.

“I remember the sound of the report of a rifle. I remember pain. I remember thinking, ‘Where did that come from, and who shot me?’ There are long periods of time that are blank. I remember SSG Morgan Gandy, one of the two medics, giving me mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. I remember how sweet the air tasted. I remember a brief period of time looking at the roof of a helicopter. I can remember receiving mouth-to-mouth resuscitation in flight.. I was in and out of consciousness during the flight and only have a vague recollection of the hospital, the nursing staff dressed in white.

“These are the memories that I have until I arrived at a hospital in the United States. I was later told later that I was at Lackland Air Force Base in the ICU. I was there for one year and then transferred to the spinal cord injury ward at a VA hospital in Ohio.”

SSG Morgan Gandy (author collection)

SSG Morgan Gandy

Special Forces Medic – July 15, 1987

“At roughly 2200H, myself and another medic, along with SSG Hodge, were off duty. We were rough housing for about three minutes in our quarters, stopping to help Tim find his watch. He’d taken it off earlier.

“I was standing by my wall locker. SSG Hodge was near our refrigerator and near the center of the room. The other medic on the team came over from his side of the room. He took my CAR-15 off its rest on the wall, chambered a round, and fired in what I considered a swift, violent motion. The bullet struck Tim in the left side of his neck. He fell to the floor. The other medic and I immediately began combat life-saving measures and were able to stabilize Tim. A MEDEVAC was requested to come from San Miguel.

“We had an M-5 medical aid bag positioned on top of the fridge in case of emergency. There was a guard duty cot close by, and my CAR was hanging above it on the wall by its sling, full mag inserted, no round in the chamber. It was SOP to pull a rotating guard from 2200-0600 due to the potential for attack. I remember that SSG Hodge walked into the room with a big smile on his face. Timothy took about one step towards me when our other medic entered the common area. He grabbed my CAR-15 off the wall, jacked the charging handle to the rear, grasped the pistol grip, and fired one round from the hip. The blast came from behind me on my right, directed toward Timothy.

“I remember thinking it was a reckless thing to do… It was not like him fooling around with weapons. I looked at SSG Hodge, who stepped forward then backward, still smiling, then collapsed to the floor. I saw three holes in the thin wall behind him, and it registered in my mind they could have been bullet fragments, bone or both. Master Sergeant JD Pruitt came in and took my weapon from the cot where it had been dropped. I grabbed the M-5 bag and went to work. The other medic immediately came to assist.

“A single bullet had passed through the base of Tim’s neck. It cut the jugular vein and compromised the jugular artery. I knew that his cervical spine had been compromised and that quite possibly bone fragments of the spinous process of C-4 or C-5 had exited the wound along with the bullet. Tim began to develop a massive hematoma from blood trapped beneath the skin, even though we were applying heavy manual pressure to his lateral neck. I wanted to clamp off the vein with hemostats, but the other medic disagreed and was worried that we might cause further damage to Hodge’s cervical spine. He was correct. We started large bore IVs.

“We put Tim into a litter and got him as warm and secure as we could. MSG Pruitt came in and told us the MEDEVAC was delayed due to heavy fog. He asked me, ‘How long we keep Tim alive?’ Tim had not said a word yet, but at that moment he looked in my eyes and barely whispered the word ‘AIR’… I started rescue breathing for him immediately. The other medic and I took turns breathing for Timothy and treating his wound and symptoms the best that we could.

“We were informed early in the morning the original U.S. MEDEVAC had crashed into a mountain, killing everyone on board except for one soldier. The helicopter that took SSG Hodge to the military hospital in San Miguel, El Salvador, arrived there safely.”

Colonel (ret) Kevin Higgins

Special Forces OPATT – San Miguel, July 2023

“The MilGrp built a nice asphalt heliport on the 3rd Brigade cuartel (1985). It included berms for eight helos. Alas, the Salvadorans only used the heliport to conduct morning PT. The Salvadoran pilots preferred to squeeze the three UH1Hs inside the 3rd Brigade quadrangle, where formations were held. One of the three helos would land 25 meters (or less) from my room. This created havoc, dust and FOD blowing everywhere. We duct-taped every crevice in our window frames to keep the dust and tiny pebbles out, but to no avail.

“The Salvadoran helos liked daylight flying. It was all logistics runs and command visits during the day. But they flew at night. They flew medevacs and support to units in contact. No admin flights. So, at 0200 hrs, if the helos cranked up, I jumped out of bed and got my uniform on. That meant something was happening.

“This happened often. Almost every night.

“When Hodge was injured, the Salvos launched that helo before I could ask. This was their chance to show their gratitude to the USA. The ‘We don’t fly at night’ comment can only have been misconstrued from ‘We don’t fly admin missions at night—only fire support and medevac.’

“I was at the Krobach crash site that night in 1987. The UH1H was flying nap of the earth, and the skid caught the treetop. It was a 20-foot tree, standing all alone out in the cow pasture. It was also in Lolotique, not far from where Picket would meet his fate in 1991.

“If [Raybon] had to do it over, he could have lifted off from 1st Brigade and head directly south to Comalapa and the Pacific, following the littoral Hwy to San Miguel. But in July, even that route could have been socked in. Plus, that would have added 30 minutes time of flight. Raybon probably imagined that every minute counted, not knowing that Hodge was already being treated in the best trauma operating room in Central America.

“By 1986, MILGP El Salvador had a superb Motorola repeater network set up across El Salvador. The 21 major volcanoes made for good high ground to set up the repeater sites. Our repeaters were co-located with ESAF sites.

“Salvador is a small country, so I would estimate that the advisor’s hand-held Motorola had at least 80% coverage of national territory. However, during the critical hours when MILGP was looking for the Raybon UH-1H, I mainly stayed on the landline in the hospital with MILGP. That was a clear and dedicated connection.

“Despite these decent lines of communication, the reports indicate some lag time (but not much) in trying to establish ground truth.

“I remember hearing an inbound helo coming into San Miguel that night, which lifted our spirits, but only momentarily, because the ESAF officer quickly said, ‘That’s ours.’

“I worked in Honduras (2013–18) then El Salvador (2018–21). They love WhatsApp. In an incident such as this, they would have quickly established a WhatsApp group that would have kept everyone apprised.

“But for 1987, that Motorola was an excellent communication network for the MILGP.”

The helipad at San Miguel. Three Salvadoran UH-1H helicopters were stationed here 24-7 to fly MEDEVAC and combat extractions such as the one sent to CEMFA for SSG Hodge on July 15, 1987. (author collection)

July 15–18, 1987 — Interviews, Ilopango Air Base /El Salvador Military Hospital, San Salvador

LTC Don Elder

MilGrp Operations Officer

“The mission was generated by me. It was initially a mission to transport medics and the U.S. adviser to the El Salvador Military Hospital to the National Training Center [CEMFA] south of La Union. Initially, it was to evacuate a U.S. adviser that had been shot in the neck. The shooting was an accident. Normally, El Salvadoran Air Force (ESAF) helicopters do that, but they only had some 14 UH-1Hs flying out of about 43. They have been involved in a big operation that has taken a toll on them.

“When the aircraft became overdue, we really began an earnest attempt to find them. San Miguel had earlier indicated our UH-1H had arrived, but it turned out to be a Salvadoran UH-1H. We contacted everyone along their route of flight. At 0244, I got a call from the El Salvador military that a local national had advised them that an aircraft had crashed and gave them the approximate location. I contacted Mr. Salazar and had him meet Colonel Ellerson [MilGrp Commander] at HELO Operations…they launched in a UH-1 toward the reported crash site near the northeast corner of Illopango Lake.

“They located the site near the top of a high ridgeline. They managed to find a place to set down. There was a survivor, but due to the terrain and location, a hoist was needed. A Salvadoran UH-1 with a hoist was requested, but it had mechanical problems. Another one was dispatched, but it also was not operating [the hoist]. We got Special Forces people there, and the Salvadoran military provided security. They rigged ropes and a sling, lowered the survivor down the ravine, and transported him to our UH-1…the others were obviously dead. Colonel Ellerson wanted to get the bodies out as soon as possible along with our U.S. security people for safety reasons. We have local troops at the site now but I won’t guarantee it is secure. There is really no way to secure it. We tried not to disturb the area any more than was necessary to get the survivor and the bodies out.”

CW3 William Hasenauer, Pilot

Pilot in Command Recovery Helo

“MilGrp was concerned about the gunshot victim. We were concerned about our lost contact with our aircraft. We tried to make them understand about the lost contact, but I guess they initially had problems of their own. I talked with the duty officer. We decided to launch another aircraft to attempt contact.

“We went out to the aircraft. It had already been pre-flighted, so we launched. We tried all the radios to contact them. We went to the north side of the lake and to the east. Then we came back and worked around the south side of the mountains and continued to make radio calls…we turned out our lights and used only the goggles.

“I saw it [the storm] coming. At that time, I witnessed cloud-to-cloud lightning out to the east. He [Mr. Raybon] must have flown into it. We got his call that he had run into a thunder bumper and he was coming back. We lost commo and shortly after that, it started raining and lightning here… The visibility was reduced to less than a mile, but it is a little different here with all the lights on the airfield.

“They [Salvadoran base security] had flares going up… There was a firefight going on just on the other side of the airfield.

“I picked up Jose Salazar and the local fisherman that hitchhiked up here to report the accident to the staff duty officer. While we were going out, Jose was talking to him. He [the fisherman] never heard the crash. Mr. Rameriz [Salvadoran farmer who witnessed the crash] told him about it. We circled around. We were trying to find the easiest way in. We dropped Colonel Ellerson, Jose, and our crew chief on higher ground. There was a field up there with a dead tree. After a few attempts, we got in. It was the closest place to them. We went back and got seven more and dropped them off at the lower area. We used only the lower area from then on.”

Sergeant Major (ret) Thomas Grace

Special Forces Medic – Crash Survivor

SFC Thomas Grace, the sole survivor of the crash, was interviewed while in the hospital in San Salvador. He was one of the two medics picked up at the First Brigade helipad in San Salvador by Mr. Raybon. Grace was unable to recount the entire event but answered some questions.

“…I was sitting in the left rear of the aircraft, looking out of the left side. When we took off, it was relatively clear. As we flew along, it began getting worse. We encountered heavy rain and clouds. I remember thinking, ‘Why aren’t we turning around?’”

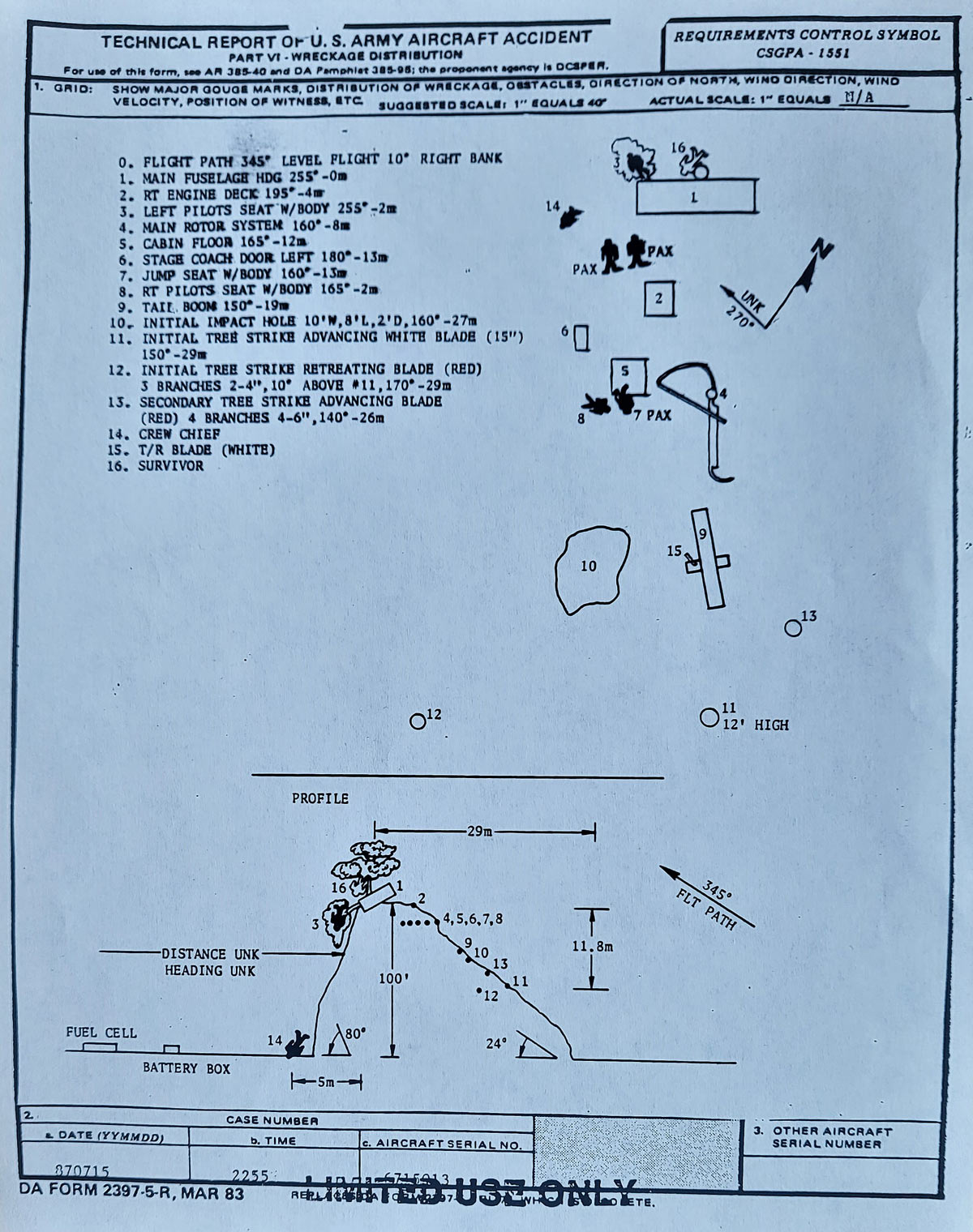

Official illustration of the crash site and location of those killed as well as the single survivor.

The Crash Site

Mr. Raybon’s UH-1H, aircraft ID number 6915013, impacted a hillside roughly 33 meters below the ridgeline. It was observed moments before the crash by a local resident, Mr. Rameriz, and his family, who had a small farm there. Rameriz made his way about 450 feet from his home up to where he found the wreckage. He saw bodies strewn around the crash site and moved one, thinking the man was still alive. He was not.

Where Tom Grace was thrown from the aircraft upon impact and survived, all those others onboard but for one were likewise, despite being buckled in, thrown from the helicopter, which impacted the hillside at an estimated 80 knots, or 92 miles per hour. Autopsy reports show the bodies of those killed suffered catastrophic injuries. The Army would strongly recommend to the families involved that the remains of their loved ones not be viewed in lieu of this.

Rameriz, upon discovering the crash, returned to his home and then told a local fisherman who had a motorcycle about the crash. That individual then made his way to a Salvadoran security checkpoint and reported the incident. It would take nearly four hours for the information to make its way to U.S. MilGrp personnel and a rescue/recovery operation mounted.

During this time lapse, it appears the guerrillas involved in the fire fight reported by CW3 Hasenauer, or their support elements in the immediate area, also discovered the wreckage. Of the personal weapons and ammunition listed in the Fort Rucker crash report as being onboard, none were reported recovered. And personal effects such as rings and watches were likewise not reported as being recovered either in San Salvador at the military morgue or the morgue at Gorgas Army Hospital in Panama.

Cause of crash—bad weather or a second aircraft near miss?

“I was not aware of this. But Ilopango would have been a busy place during the night. The FAS helos launched at night on two conditions: Medevac or a unit in contact. The three UH1Hs in San Miguel serviced Usulutan, San Miguel, La Union, and Morazan. Ilopango took care of the rest of the country. The likelihood that Raybon would cross paths with another helo near Ilopango was high.”—Colonel (ret) Kevin Higgins, Special Forces, July 1, 2023

“Mr. Walker, the Aviation Safety Network, Flight Safety Foundation, is not affiliated with the U.S. Army Combat Readiness Center. The Flight Safety Foundations is an independent, non-profit organization. I wished I could find this incident for you, but it is not in our database.” —Joy Purinton, Combat Readiness Center, Fort Rucker, Alabama, May 30, 2013

In 1993, an Army helicopter pilot who had been stationed in San Salvador sent me a picture. It was of a UH-1H that had crashed in Lake Illopango on the same day and year that Chief Raybon’s MEDEVAC flight had gone down. It was reported those onboard remain in Lake Illopango.

While researching this story, I was referred to the Flight Safety Foundation and its Aviation Safety Network (ASN) report. This report has long been a reference for Army aviation crews. For example, the crash of UH-1H, ID number 69-15013, is available through the ASN. I ran the aircraft identification number for the UH-1H as it appears in the photo I was sent now decades ago. Aircraft registration number 69-15383 is reported to have crashed on July 15, 1987. No fatalities are listed; no number of occupants is listed; the crash is listed as being military related with the caveat “Little or no information is available”. — https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/77028

And the Aviation Safety Network’s report on Chief Raybon’s aircraft — https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/200466

Regarding the events of that tragic evening at Illopango, one individual with extensive knowledge of the war in El Salvador and this specific incident offers the following. I am honoring his request for anonymity given his role. “The ‘cone of silence’ remains. That said, agree Rucker’s [crash report] is excellent. Continue to just present the facts. That should bring the real truth to the surface and bring recognition to those involved.”

The masking of the ownership and circumstances of UH-1H #69-15383 may be tied to the March 26, 1987, crash of a Salvadoran UH-1H piloted by CIA aviator, Richard Daniel Krobock. Krobock, a former Army aviator and officer, had joined the CIA just five months before his death. He was on a search and rescue (combat extraction) in support of ongoing U.S./Salvadoran special operations when, while flying nap of the earth under NVGs, one of his skids struck a tree top. Krobock was well suited for duty with the CIA. His military career included Ranger School, Flight School, Airborne School, Armor School, and Military Intelligence School.

The young aviator joined the CIA in October 1986 while stationed at Fort Ord, California. He was assigned to the Agency’s Directorate of Operations, Special Activities. On March 26th, Krobock was the radio communications officer onboard his aircraft. While returning from a successful extraction during an Agency operation the helo crashed, killing all onboard. Although no cause was given for the accident, Colonel (ret) Kevin Higgins visited the crash site that same night. According to Higgins, Korbock’s aircraft was flying across an open field, nap of the earth, when it struck a treetop. “It was the only tree, about 20 feet tall, in the field,” recalls Higgins today.

— https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/200250

With the combat related death of Special Forces sergeant Greg Fronius on March 31, 1987, followed by the combat related death of Captain Richard Krobock, and then the July 15th deaths of another six Americans with two Special Forces soldiers injured/wounded, as well, the U.S. Congress was demanding answers as to what was really going on in El Salvador?

Wreckage of the second UH-1H at Lake Illopango on July 15, 1987. In the “fog of war” that night did a CIA piloted helicopter experience a near-miss with Chief Raybon’s Huey with the ensuing accident taking place? And what of the crew’s fate that night? Were they also recovered or do their bodies remain in Lake Illopango to this day?

At stake was the War Powers Act— “…officially called the War Powers Resolution—was enacted in November 1973 over an executive veto by President Richard Nixon.

“The law’s text frames it as a means of guaranteeing that “the collective judgment of both the Congress and the President will apply” whenever the American armed forces are deployed overseas. To that end, it requires the President to consult with the legislature “in every possible instance” before committing troops to war.

“The resolution also sets down reporting requirements for the chief executive, including the responsibility to notify Congress within 48 hours whenever military forces are introduced “into hostilities or into situations where imminent involvement in hostilities is clearly indicated by the circumstances.”

“Additionally, the law stipulates that Presidents are required to end foreign military actions after 60 days unless Congress provides a declaration of war or an authorization for the operation to continue.” — https://www.history.com/topics/vietnam-war/war-powers-act

Burying the Dead with Dishonor

Several years after his wounding in El Salvador, Tim Hodge called the teammate who was responsible for his life-changing injury. Hodge felt no animosity toward the man he considered one of his closest friends at 3/7th SFG(A) in Panama. In fact, the same individual had immediately come to his aid along with SSG Morgan Gandy.

When Tim asked his friend, now reassigned to another Special Forces unit stateside, what had happened that night he was told “I can’t talk about it. It’s classified.” They never spoke again. The soldier had been court-martialed after the incident, demoted one rank, and allowed to remain in the Army as no criminal intent was found to have occurred. A records check shows he completed his military career and passed away nearly a decade ago. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Those who knew him offer he never recovered from the knowledge that his errant handling of SSG Gandy’s weapon had cost his friend, Tim Hodge, so much.

And that it had brought about the deaths of six other Americans sent to bring SSG Hodge to safety.

There was exceptional heroism and certainly honor in the actions of all those involved in the MEDEVAC effort of July 15, 1987.

There was no honor to be claimed by those who misrepresented what had occurred, at both CEMFA and Illopango, and either openly lied to or quietly mis-directed those questioning the circumstances of the two events so as to sustain the public policy of no combat role for American service personnel in El Salvador. This deception included the grieving families, too.

This policy would continue through 1992 when the UN-brokered Peace Accord was signed and El Salvador’s 10-year long civil war was ended. In 1996, through a grass roots political effort, the Congress of the United States authorized the Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal and accompanying combat awards and decorations for all those U.S. service personnel who served and fought in El Salvador.

— https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a3uy8Ey23Is

Lest we forget.

Read more by Greg Walker about the 1985 attack on CEMFA articles as originally published in Behind the Lines Magazine in 1993. The articles really bring home the true danger of serving at CEMFA.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR — Greg Walker is an honorably retired Special Forces soldier. His awards and decorations include the Combat Infantryman Badge (2 awards), the Special Forces Tab, and the Legion of Merit. Walker was part of the MTT to El Salvador in 1984 that established the National Training Center (CEMFA) in La Union. Today, Greg lives and writes from his home in Sisters, Oregon, with his service pup, Tommy.

The author in La Union, El Salvador, 1984. (Courtesy Greg Walker)

SSG (ret) Tim Hodge was paralyzed for life as a direct result of his wound. He spent a year in Texas at an Air Force hospital, then another 4 years in the spinal injury ward at a VA hospital in Ohio. He was hidden away by the Army / DoD given the political considerations at the time. Although Purple Hearts had been awarded to SF soldiers wounded in El Salvador (Jay Stanley / George Reyes, the latter wounded in the leg by his team leader who was showing off his “fast draw” with his .45)…SSG Hodge never received a recommendation for a PH. This past week he sent the Army’s Human Resources Command a military records correction packet with cover letter recommending approval from Major General (ret) Ken Bowra (Special Forces / DELTA/MACV-SOG). Tim was one of the original CIB recommendations made by the Council of Colonels, J-5 Staff, chaired by Colonel (ret) John McMullen. Tim’s packet includes that documentation along with a corrective request for award of the CIB and the Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal for El Salvador.

SGM (retired) Anselmo Martinez reached out with this additional first person account of the night of the crashes and wounding of Tim Hodge – my sincere appreciation is extended to the SGM and his message was first shared with Ms. Lujan, Tim Hodge, and Morgan Gandy prior to being presented here. Sadly, not all the personal effects of the deceased were recovered per Ms. Lujan regarding her husband’s wedding ring and watch.

“Thank you for the prompt response. The night of the accident I was at the Medical Team house with another team member (SSG Alberto Garcia ) and of course monitoring our Motorola radios. Garcia told me and I quote, ” We just lost a bird”, since he was paying close attention to the communications going back and forth. We immediately left the house enroute to the Military Hospital since it was our place of duty. We spent the night waiting for news and the recovery efforts. It took all night for the bodies to be brought back to the morgue. it was at that time that I recognized LTC Lujan, he had been to Fort Bragg (JFK antiterrorism training) with me prior to departing to El Salvador.

There was another Laboratory Technician with me as part of our team (SSG Juan Garcia) and it became our responsibility to body bagged all six bodies in preparation for sending them to Panama for further investigation (autopsies?). With the exception of one of the pilots who had a compound fracture on a leg, everyone else suffered the expected trauma due to the impact. Everything they had in their possession was left inside the individual body bags. Once the bodies were picked up from the morgue SSG Garcia and I had no other communication with the Mil Group Chain of Command or anybody else.”

Ms. Lujan, upon learning of the crash and her husband’s death, called the number he’d left for her if something were to happen to him. One of the questions she had was about his personal possessions. She requested and was sent his dog tags (with specks of blood still on them), his beret, and his medical records. When she began asking questions and filed a complaint with CID at Fort Bliss, Texas, she was told LTC Lujan was identified per his medical records. She replied that was untrue. She was asked why she would think that? She replied “Because I have his medical records!”. The next day CID showed up at her door and demanded the records back. She gave them most of them – but kept a few pages out – the CID investigation was closed.

As of this past week it is my understanding the other UH-1H involved in the crash of Chief Raybon’s MEDEVAC bird was CIA “owned and operated”. The Agency’s war in El Salvador increased year by year beginning in 1980. By 1987, the Agency had its air assets, crews, and paramilitary operators fully engaged in El Sal. They’d lost an increasing number of aircraft, fixed wing and helo, and personnel by the time the Illopango crashes took place. At the same time, DELTA and Task Force 160, their air asset, were likewise heavily involved in El Salvador conducting reconnaissance and direct action missions against FMLN guerrilla forces. Chief Raybon, for example, was a DELTA/160 pilot. What is clear is this. Illopango that night was under guerrilla attack and “a major operation” was taking place elsewhere in the country. Weather was likewise poor in and around Illopango that evening. The control tower was overwhelmed in trying to keep track of what they had in the air and communications had been lost with Raybon. No one knew where he was on his return to base. As likely as not the Agency helo was either departing or returning to Illopango and a near collision took place between it and Chief Raybon’s AC. Wreckage from the CIA helo was found on the shoreline of the lake as seen in the picture of this wreckage sent me in 1993 by an Army helo pilot who had flown in ES. Were the bodies of those killed recovered? If so, or if not, that information is under strict lock and key. Just as Part II was published I received a reply from U.S. State Department regarding this incident. “No records found”. Why? – “ Admit nothing….” “Inconceivable no record of cables. Very likely all were destroyed IAW directives.” – No Fallen Comrade Left Behind rule is in effect.

As usual for those who have read Greg Walker’s work, his research and attention to all the details is flat out amazing. He has spoken out about the missions and actions of our government for decades. His work has set the conditions for many to finally learn the truth about their loved one’s.

Doc Keen, others, and me were attached to a SOTA team in the summer of 1984 running real operations out of Palmerola to the ES-Hondo border as a sideshow of Ahuas Tara 2/ JTF Bravo. Chief Raybon was one of our Huey pilots. I have the utmost respect for them.

I met Capt. Dan Eagan at Auburn University and heard the story about the 1985 attack on La Union. He did not mention his heroics in repelling the attack, but he did show me photos of what was left of his quarters after the FMLN tossed a satchel charge into it. He mentioned casualties in excess of 130 soldiers and other interesting details. If you are in contact with Dan, please send him my best.

If you have contact with Dan Eagan, please let him know I still have the autographed copy of “Facing the Volcano” that I will be happy to return to him.