A DEFECTOR IN PLACE: The Strange and Terrible Saga of a Green Beret Sandinista – Part Two

Editors Note: Be sure to read “A Defector in Place: The Strange and Terrible Saga of a Green Beret Sandinista Part One” if you haven’t done so already.

By Greg Walker (ret)

Prologue: How Not to Raise a Revolutionary Army

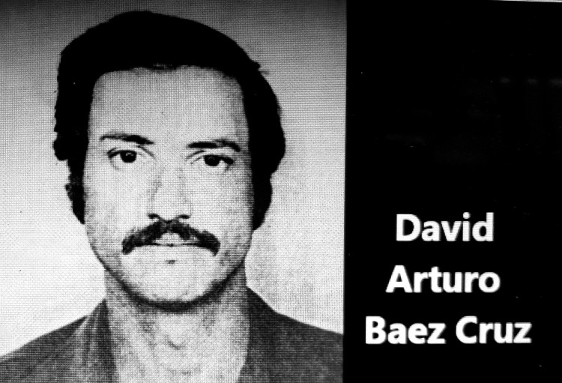

In August 1980, Green Beret David Arturo Baez was honorably discharged from the United States Army for compassionate hardship reasons. His carefully constructed ruse of having to return to Nicaragua to help his aging grandparents on their small coffee finca had fooled his command at the 3/7th Special Forces Group (A) in Panama, as well as the United States Army.

In fact, the government led by the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) had nationalized Nicaragua’s coffee industry beginning in 1980. The FSLN purchased and sold all the country’s coffee, using the hard currency earned on the international market to finance its revolutionary war against the U.S.-backed Contra movement, supported by and from Honduras.

Now a major in the Sandinista Popular Army, David Arturo Baez Cruz agreed to accompany Dr. Reyes Mata and the FAP on its mission to wage guerrilla war on the government of Honduras. Baez Cruz would serve as Mata’s bodyguard, described by deserters from the FAP as “always being near him” during the march. (YouTube)

Part Two – Once a Green Beret, always a Green Beret

In 1981, while conducting a clandestine intelligence gathering mission in Managua, retired Lt. Col. Bill Chadwick, a Special Forces officer; and Lt. Col. John Lent, encountered now-Lt. David Baez in the uniform of a Sandinista officer. Recognizing each other from 3/7th, the trio had a brief conversation, then went their separate ways. Previously, Baez floated another story around the battalion that he was forced to return to Nicaragua by its new government, and in order to protect his family, would have to join the Sandinista Popular Army (EPS). So the chance encounter between the three men was friendly.

The bond between Special Forces soldiers holding fast as Baez could easily and to his benefit betrayed the two officers.

Chadwick recalled that the two American officers swiftly reported their encounter to the U.S. Southern Command J2 and its counter-intelligence team. David Baez was now officially on the radar screen and a known enemy threat.

Assigned to the Combat Readiness Directorate, Baez’s first assignment was to train an EPS special unit of paratroopers. This he did with enthusiasm. The assignment was also seen as a means of monitoring the former American Special Forces soldier. “Trust but verify” was an important maxim for the Sandinistas. After training the paratrooper unit, Baez turned his expertise and the information he’d gathered as an AST in El Salvador toward the early formation and training of the EPS Irregular Warfare battalions (IWB). These battalions meant specifically to conduct counter-guerrilla warfare against the Contras. Strangely enough, the IWBs closely resembled the new Immediate Reaction battalions of the 3/7th mobile training teams in El Salvador in 1980–1981.

A born-again Sandinista

By 1982, Baez established himself as a born-again Sandinista. Promoted to the rank of captain, he volunteered for combat duty and was assigned to the “Pedro Altamirano” battalion of the EPS, then based at Montelimar. According to his brother, Eduardo Baez, Capt. Baez “would travel daily from El Crucero where we lived” to Montelimar to work. When his battalion deployed to the rugged Kilambé region of northern Nicaragua, Baez was an invaluable asset on the ground.

After many months of combat duty, he was assigned to a special troop three-man mobile team that specialized in detecting and tracking Contra infiltrations along the no man’s land corridor between Honduras and Nicaragua. The mobile team relied on jeeps to transport the team and its sophisticated Soviet-supplied radio intercept equipment to accomplish its missions.

Then, in April and May of 1983, Baez visited his brother and shared his next assignment. In his August 2001 interview with Roberto Fonseca of La Prensa, Eduardo recalled that sad moment. “He had volunteered to leave with a Honduran guerrilla column. He did not know if he would return or not. He asked me to take care of the children…you know, that kind of personal stuff.” Captain Baez, perhaps recalling the grief and pain that his family endured when his father disappeared in 1954, made a contingency plan should something similar happen to him.

“He also recommended,” said Eduardo, “that if [we] heard any news about the capture or [death] of a guerrilla in Honduras, under the pseudonym Adolfo [their father’s first name], that I would know it would be him.” Baez told his brother he wrote a farewell letter to his youngest son, just three months old, “We had a few drinks, we cried, we said goodbye and he left,” recalled Eduardo in 2001.

The Honduran guerrillas would be wearing Contra-style uniforms for their infiltration and carrying American-made weapons to include M16 rifles, M79 grenade launchers, M60 light machine guns, and 1911 .45 caliber pistols. Each fighter had a nom de guerre, or “guerrilla name,” for security reasons. Baez, like the others, would go in sterile–without any incriminating forms of official identification. He was used to playing this role from his training and experiences at both 10th Special Forces Group (A) and later as an AST in Panama.

If Baez were captured or killed and identified as a former Green Beret and now Sandinista officer, there would be diplomatic hell to pay with both the U.S. and Honduras.”

His presence as both an assigned bodyguard for a high-ranking official [Dr. José Reyes Mata] and an EPS combat adviser to the column was a carefully considered risk for the Sandinistas. If he were captured or killed in Honduras and identified as a Sandinista officer, especially as a former Green Beret and now Sandinista officer, there would be diplomatic hell to pay with both the U.S. and Honduras.

At the same time the column began its infiltration, Daniel Ortega, coordinator of the Governing Board of Nicaragua, proposed a six-point peace plan to end the Contra war. Ortega was playing with fire.

Dr. José Reyes Mata, whose nom de guerre for the Armed Forces of the People (FAP) campaign would be Comandante Pablo Mendoza, reminded himself of this situation when he wrote about it in his war diary after capture. “Our movement is extremely politically compromising. And we will not disappoint those who have placed their trust in us.”

Dr. José Maria Reyes Mata, also known as “Comandante Pablo Mendoza,” possessed a long history of Marxist guerrilla actions: with Che Guevara in Bolivia; again in Nicaragua with the Sandinistas; and later with the PRTC in El Salvador. He was a convicted terrorist in Honduras, imprisoned for kidnapping, and released in 1982. (El Mundo).

Operation CONDOR spreads its wings

General Gustavo Alvarez, CinC of the Honduran Armed Forces, said in a recent speech that the military will come down hard on terrorism and that the philosophy of human rights was not created to protect terrorists or subversives, nor was it created to protect those who receive training in sabotage and guerrilla operations.” – U.S. DOD Joint Chiefs of Staff Message Center

General Gustavo Adolfo Álvarez Martínez was known throughout Central and South America for saying what he meant and meaning what he said. He’d entered the Honduran Army on April 12, 1958 and attended the National Military Academy in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Upon his return to Honduras, after a successful command with the 2ndInfantry Battalion, he was commissioned as a 2nd Lt. in February 1963. Later that year, in October, he was selected to attend the U.S. Army Special Forces Counter-Insurgency school at Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

“Those” included not only Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua but Fidel Castro in Cuba. Castro provided a year’s training for the new guerrilla army in 1982 at the Cuban Army’s Special Troops training base at Pinar del Rio, located just 90 minutes from Havana’s Jose Marti Airport.

By now, the 96-person column–brought back from Cuba in ones and twos–was assembled in a safe compound outside of Managua. Security conditions were strict. No leaving the compound, no female visitors, no contact with families, and no money. Individuals who deserted were captured and immediately put into a Sandinista prison. Reyes Mata didn’t see this red flag for what it was: the unhappiness and dissatisfaction of some people who didn’t “volunteer” to be guerrillas in his revolution but rather press-ganged into the movement with promises of civilian occupation training in either Managua or Havana.

Reyes Mata’s recruiting efforts occurred in Honduras’ Olancho province by local Revolutionary Party of the Central American Workers (PRTC) Honduran agents, as well as “guerrilla priests,” many of these Jesuits. In a 1984 Miami Herald story (“Deserters Say Foreigners Fight for the Sandinistas”, Guy Gugliotta), Arnulfo Montoya Madariaga, then 35, described his recruitment in 1981. A campesino with a plot of land and seven children, he was recruited by “a French priest at his farm outside Danlí in southern Honduras.”

By September 21, 1983, 23 FAP combatants deserted, were captured, or turned themselves in to Honduran forces. The first desertion took place within two weeks of the FAP July crossing the Coco River in platoon-size elements. By the end of August, deserters provided the Hondurans and Americans with detailed descriptions regarding the platoons, personnel, leadership, weapons, communications, and the logistical support for the column. “Disgruntled employees” and empty stomachs marked the beginning of the end for Baez & Company

Honduras is “peaceful and friendly”

The FAP was combat-ready. The column’s members were broken down into smaller groups of combatants and farmed out to the IWB of the EPS for another six months of fight training the Contras. On January 11, 1983, FAP commanders “LaPorta” and “Marcos” gave detailed reports about ambushing “an entire enemy company, which in its confused flight, left behind weapons, supplies, and a large quantity of rations.” The FAP continued working alongside the EPS until final preparations began for their infiltration into Honduras in mid-July.

“Before leaving, I explained to everyone that our movement must not be noticed by the enemy, and that secrecy, precaution, silence, and initiative would be our principal weapons…based on the information obtained from the enemy which I checked, they were waiting for us, to liquidate us and the daring plan for a march, flanked by enemy [Contra] camps. Everything seemed uncertain.” – from the captured war diary of Dr. José Reyes Mata (Comandante Pablo Mendoza), July 15, 1983.

In Honduras, there was little concern about such an incursion. Although the September 1982 assault on the San Pedro Sula’s Chamber of Commerce building was Cinchonero Popular Liberation Movement was dramatic–100 hostages taken, including three senior officials of the Honduran government–it ended after eight days, with no guerrilla demands granted.

The hostage takers were flown to Cuba on a Panamanian air force cargo plane. Catholic clergy were involved in the negotiations. The UPI reported, “The official said San Pedro Sula Bishop Jaime Brufau and Papal Nuncio Andrea Cordero Lanza, the chief negotiators throughout the takeover, were to accompany the guerrillas on their flight to Cuba.”

Platoons Across the Coco River

“The march was programmed through topographical [illegible] or “This report provides an update on the HO [Honduras] infiltration…As of 26 August 83, a total of 17 guerrilla deserters from the 96-man guerrilla company called The Armed Forces of the People or F.A.P.–Fuerzas Armadas Del Pueblo–have been taken into custody…Efforts continue to locate the remaining guerrilla force which infiltrated from NU [Nicaragua] into the HO Olancho Department on 19 July 83 to “Make War on the Country.” Further details on the organization and Order of Battle for the guerrilla unit is provided along with an updated list of guerrilla deserters…” – DOD Joint Chiefs of Staff Message Center, August 30, 1983 / DECLASS 1/90, DOD Telegram #09347

On July 15th, Reyes Mata and his platoons moved to their jump-off point on the Nicaraguan side of the border. The weather was miserable. Never-ending rain turned the trails to slick, sticky mud. The men, carrying their weapons and 60-70-pound rucksacks, slipped, fell, and cursed as they struggled up the steep mountainside to make camp. Still, morale was good. “I wanted to inspect the camp’s defense system. This required a great physical effort on my part, because the prolonged sedentary existence had left me out of shape,” Reyes Mata wrote in his diary that evening.

The goal was to have the platoons across by July 19th. Ten days earlier 2nd Lt. “Justo Martinez” led a reconnaissance patrol into Honduras well ahead of the main body. A single boat ferried the men and their equipment across the Coco River. Before the first crossing, Padre Guadalupe Carney formally christened it the Granma in honor of the 60-foot motor launch Fidel Castro used to transport his 82 guerrillas from Mexico to Cuba in 1956.

Reyes Mata planned for measured rations, with a belief the men could purchase food from local farmers or gather sustenance from the jungle. He was wrong.

The heavy rains filled the Coco higher than expected, and nighttime infiltration turned into a harrowing process that wasn’t completed until broad daylight of the first day. However, by the 19th three of the four platoons were across without the loss of material or men. The last platoon, responsible for additional rations and equipment, couldn’t cross safely until July 21st. Lieutenant Martinez’s recon team was 80 kilometers inside Honduras and in radio contact with the main body. Eight days were planned for the platoons to traverse the steep mountains and triple canopy jungle to their first base camp. Reyes Mata planned for just enough rations, with the belief men could purchase food from local farmers along the way or gather extra sustenance from the jungle.

Meanwhile, the FAP had to thread the deadly needle’s eye between Honduran Army and Contra patrols. The Contras had a significant presence in the towns of Yamala and Chilamata, well within patrolling distance of the FAP’s route. As the FAP consolidated itself in preparation to begin its journey inland, a second Nicaraguan officer from the Intelligence Directorate arrived. Known only as “Gregorio,” he was welcomed to the camp, along with another EPS officer, “Adolfo”–or Comandante David Baez. Reyes Mata wasn’t privy to “Gregorio’s” reason for joining them, but it can be presumed it was to monitor the progress of the FAP and then return to Managua to make a report.

On July 23rd, a Contra who’d stumbled upon the tracks of the column and followed the guerrillas for three hours, was captured and summarily executed.

The eight days of stealthy movement turned into 12. The weather remained miserable and the guerrillas, used to eating every day, soon ran low on food as the misery of the terrain sapped their strength, slowed their pace, and consumed vital energy they couldn’t replace. The trail soon became littered with equipment tossed to the side as guerrillas tried to lighten their rucksacks. Reyes Mata was feeling the strain as well as “Mario,” or Padre Guadalupe. At one point, when the march had sped up after being seen by a local, he wrote “…we gave the order to hasten the march toward Point A…Mario gave evidence of his great capacity for sacrifice, and I was able to move better with only my equipment and rifle.”

After arriving at Point A, the main body continued on until arriving at Point B, the pre-determined site of its first base camp. However, upon arriving, Reyes Mata was informed a campesino was captured by a stay-behind team charged with watching their back trail. The man was interrogated and then executed.

It had to be done with a knife,” wrote Reyes Mata, “there was no other [option], given the place where we were [being] surrounded by enemies.”

By now, Comandante Pablo Mendoza revealed himself to be as being as cold and remorseless as his mentor, Che Guevara. Anyone who attempted to desert was shot. Anyone deemed a threat or determined to be a traitor received the death penalty. For Reyes Mata, there were no other options. Victory was the only reward.

At Point B they were met by Comandante Serapio Romero and selected members from the 2nd platoon who had arrived the day before and secured the site. However, the Lieutenant Martinez’ recon team’s information proved inaccurate as to its suitability and that night the guerrillas suffered for it. “The comrades were sleeping on the ground in groups, like rats,” wrote Reyes Mata. “And the cold froze us even to the bone.” The next morning, the FAP moved several kilometers north where they discovered “an inviting and excellent site” they named Congolon. It was now July 26th and to celebrate reaching Congolon, the guerrillas ate the last of their rations.

From July 27th until September 15th, when the last of the guerrillas would surrender and/or be captured by the Honduran Special Forces, the FAP subsisted on palm hearts, monkey, turkey, tapier, raw snails, and even the bones of game they managed to kill. There was no arrangement with the EPS to resupply the FAP, even if such a resupply was possible. Reyes Mata put all his faith in being able to buy food in Nueva Palestina from an FAP collaborator in place. It was an estimated 10-day round trip on foot. He sent six guerrillas led by Lieutenant Martinez to the village while the rest of the men foraged in the jungle.

“The group is beginning to deteriorate, and my ulcer is undergoing an ordeal by fire…we have spent only three days without food replacements. Hunger is reflected on the faces…the comrades are chewing everything: leaves, dried fruits, juts (snails), and even pieces of toasted bone. On 30 July, with only four days of lacking food, “Marvin” asked to speak with me…he wanted to return home…Hours after talking with me he deserted his observation post…[we] could not catch him…he crossed the river behind our backs.” – Dr. José Reyes Mata, Guerrilla War Diary, Olancho Province

David Arturo Baez Cruz (standing, center) relied on his extensive training and experience on the Special Forces Airborne Instructor team (ODA-5) at Fort Sherman, Panama, to train the first Sandinista airborne Special Troop. Baez Cruz would later become instrumental in training the first EPS Irregular Warfare Battalions, whose mission was counter insurgency against the Contras. (Juan Tamayo)

The U.S. government and its Department of Defense (DOD) devoted their attention, efforts, and resources toward emerging wars in Nicaragua and El Salvador. The illegal Contra campaign required careful planning and sleight of hand by the Joint Chief of Staff and CIA. The unexpected success of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front(FMLN)–already operating in battalion size units that were destroying El Salvador’s unprepared army–had Washington concerned the country would fall to the Marxists by 1983.

Meanwhile Honduras was painted by glowing U.S. embassy reports as “peaceful and friendly.”

For Reyes Mata, it was imperative for the Honduran PRTC/FAP units to have boots on the ground as soon as possible. The incursion was in the planning and training stages for nearly two years. A great deal of money was invested in it by Cuba, Nicaragua, and the Soviet Union. In El Salvador, the FMLN, paired with its faction of the PRTC army, was close to victory. Nicaragua’s FSLN victory, with its PRTC division contributions, had only taken four years from start to finish.

In 1980, the PRTC in Guatemala struggled to establish itself against an exceptionally no-holds barred counter-insurgency campaign spearheaded by the Guatemalan Army and its intelligence services. If the PRTC/FAP could establish itself in Honduras and begin a successful phase one insurgency against the government, it could count on cross-border logistical support from its sister organizations as well as the PRTC force in Costa Rica. This, in turn, would unite the diverse anti-government factions inside Honduras itself to support the PRTC/FAP.

All that remained necessary was to establish a liberated zone, beginning with the Olancho province, and a strong internal network elsewhere in the country.

“I believe,” Reyes Mata wrote in his war diary while on the march, “…the entire Entre Rios mountain range should be considered in the future as a military stronghold for us, given the native and ‘nica’ enemy concentration, and the facility it offers for carrying out guerrilla tactical movements…the jungle is so dense it would be possible to conceal within it military forces consisting of over two thousand combatants.”

Plus, as a revolutionary, Reyes Mata was now a viejo, or “old one.” At 39, with many hard campaigns behind him and several recent years of sitting behind a desk in Cuba and Nicaragua, he needed to get back in the saddle for one last chance at success in his native Honduras. Suffering from ulcers and admitting in his diary he wasn’t in the best physical condition for the campaign, the addition of newly promoted Comandante David Baez by the Sandinista leadership as “the old man’s bodyguard” wasn’t lost on him.

Padre Guadalupe, the chaplain-warfighter

“The march was programmed through topographical [illegible] or mountainous roadbeds, which would require quintupling the physical effort, and climbing up and down slopes that were very nearly vertical, on muddy terrain, and almost always under rainfall…Mario, an example of heroic campaigns, could not carry his rifle over his shoulder, and I was totally out of training.” – Dr. Reyes Mata, Guerrilla War Diary, Olancho Province

Padre James Francis “Guadalupe” “Mario” Carney, a World War II combat veteran, renounced his U.S. citizenship as a Jesuit priest in Honduras. He became a naturalized Honduran citizen, but had citizenship stripped from him in 1979. After a brief stay in the U.S., he resided in Nicaragua where he became deeply involved with the PRTC-Honduras as well as the Sandinista FSLN. (Radio Progresso)

“Mario,” later identified as Padre Guadalupe, was James Francis Carney, an American. Carney served as an Army combat engineer and then military policeman in the European theatre during World War II. After the war he became an ordained priest and was a missionary to then British Honduras from 1955 to 1958.

Padre James Francis “Guadalupe” “Mario” Carney, a World War II combat veteran, renounced his U.S. citizenship as a Jesuit priest in Honduras. He became a naturalized Honduran citizen, but had citizenship stripped from him in 1979. After a brief stay in the U.S., he resided in Nicaragua where he became deeply involved with the PRTC-Honduras as well as the Sandinista FSLN. (Radio Progresso)

In 1961, he joined the Jesuit Order, which sent him to Honduras. Carney, who adopted the first name Guadalupe, spent 18 years in Honduras and was beloved by the Hondurans he lived with and cared for. He renounced his American citizenship and became a naturalized Honduran during this time, but in 1979 the Honduran government stripped his citizenship and exiled him.

Carney embraced liberation theology, and his trajectory toward its roots in Marxism made him undesirable. He wrote his autobiography, To Be a Revolutionary, in Nicaragua, where he was welcomed by the new Sandinista government. In it, he offered “…being a Christian demands being a revolutionary and a socialist, and to be a revolutionary and socialist one has to use the Marxist-Leninist science of analysis and transformation of the world, then a Christian needs to understand Marxism.”

Prior to relocating in Nicaragua, Carney returned to the United States, specifically St. Louis, where he participated in an eight-day retreat at Jesuit Hall on the St. Louis University campus. There, he shared his dream of becoming a chaplain for Honduran revolutionaries. “I want to help a poor army,” he told his spiritual adviser.

He obtained a valid U.S. passport again and returned to Nicaragua as his being a priest, under U.S. law, overrode his renouncing his U.S. citizenship. He traveled to Cuba to train as a guerrilla. It was during this time he encountered Mata and the PRTC of Honduras, agreeing to join the new FAP.

“It still took me a couple of years to clarify my ideas about a Christian and his or her place in armed revolution.“

However, this time Carney embraced the role of chaplain-warfighter, as he would be armed. He wrote “After having sworn during World War II that I would never kill a person…it still took me a couple of years to clarify my ideas about a Christian and his or her place in armed revolution. During 1975, with its violent repression, my ideas on the Christian use of arms became clearer. I was gradually and finally [italics mine] acknowledging to myself the truth that love sometimes demands fighting back.”

However, when Carney picked up his FAP-issued M16 rifle and pistol, he gave up chaplain protections, as outlined by the Geneva Convention (GC) II of 1949 and the Additional Protocol 1 in 1977, which address what chaplains are to be afforded on the field of battle or in captivity (as opposed to “ministers of religion,” a different category altogether). Honduras became a signatory to the GC 1-IV in 1965. It affirmed its commitment to Protocols I and II in 1995, and to Protocol III in 2006.

Prior to joining the FAP, Carney shared with his Jesuit order what his intentions were. He was asked to resign but allowed to keep the title of Father. Once with the FAP, he carried his weapons, a bible, his liturgical vestment, and his chalice.

Carney was assigned to the FAP’s 3rd Platoon, responsible to establish the Central Front which would conduct combat operations in the vicinity of Tegucigalpa, Choluteca, and Danlí. Sub-Comandante “Fidel” commanded the platoon. He was also a medical doctor and the FAP’s radio operator. The platoon’s political officer was Capt. Vela, also known as Juan Ramon. Carney was a combatant in the platoon’s 3rd Squad under 1st Lt. Jackson Morales. Carney would be initially identified by both his taken name — Padre Guadalupe — and his war name — “Mario”.

In a highly classified report, obtained by the U.S. Defense attaché in Honduras from the Honduran military, the FAP’s Table of Organization and Equipment was revealed by name and in detail. The information was gathered over the course of the month from 17 FAP deserters/prisoners, willingly provided to Honduran G-2 Intelligence and verified by their U.S. counterparts in-country. “Mario” is described as “Possible [emphasis mine] priest. Name is either Fausto Milla or Guadalupe and is thought to be 60-65 years old.”

Apparently, none of the 17 guerrillas in custody at that time were truly sure if “Mario” was a priest…or a combatant.

[Note: Father Milla, a Honduran, was also a liberation theology priest. He witnessed the U.S.-backed 1954 coup in Guatemala as well as some of the early massacres by the Salvadoran Army in 1980. Accused in Honduras of hiding weapons for guerrilla factions, and of being a guerrilla himself, the padre was taken into custody by Battalion 316, which interrogated him using torture for a week. He was unceremoniously dumped in the street by his captors upon release. Fausto Milla is an icon to revolutionary and resistance movements in Central America–so much so that in 2011, he and his assistant were again forced to flee Honduras in lieu of yet another coup d’état that resulted in renewed death threats against him.]

Death by execution…and starvation

On August 2nd, three more guerrillas deserted, taking all their equipment and weapons. The next day, one more. Reyes Mata suspected a plot against him, an assassin still in camp. He ordered the arrest of “El Paisa,” whose real name was Juan Ortiz. “El Paisa” was suspected of sinister thinking and plans while training in Cuba but there wasn’t proof. Now Reyes Mata believed the proof was in the desertions–there was a counter-revolutionary in the group.

“El Paisa” was arrested, tried in military court, and declared guilty. He was executed in front of all those present in camp. For many, the killing was traumatic. They all knew him–trained, lived, and fought with him. If the chiefs could order “El Paisa” killed, anyone was at risk.

Lieutenant Martinez and his group hadn’t returned from Nueva Palestina, so the men continued to forage. “Daniel”, another doctor, treated everyone the best he could. Reyes Mata ordered Comandante Serapio Romero to take the 2nd Platoon, responsible for opening the Eastern Front in the Sierra Agalta mountains of Catacamas, to leave Congolon and head for Nueva Palestina.

On August 10th, the remaining platoons departed base camp in a forced march. There had yet been any hostile contact with the Honduran Army or Contras, although one patrol was seen, and a paramilitary with an AK-47 stopped and talked with some of the guerrillas. This man, judging the group in their Contra uniforms, determined it was okay.

It took two days to catch up with Romero and the new base camp. Reyes Mata recorded that “Mario” and some of the others who struggled “were responding well.” However, Captain Vela fared poorly. By August 15th, the guerrillas were without meaningful nutrition for 19 days but resumed their march. Reyes Mata believed his ulcer was hemorrhaging badly, but after consulting with physician “Fidel” determined the color of his stool was the result of his consuming calamus, a plant known for its vitamins.

“Mario” was traveling with and attending to Captain Vela. Presumed to be the weakest of them all, Reyes Mata noted in his diary entry that “Mario” had “reached the ravine about 600 meters from [our] camp. No one expected the state of utter exhaustion Vela was now in.” A physician was sent to the ravine, but upon arrival, discovered the starving guerilla lost consciousness. Provided what medications were still available, the man seemed to rally, or as Reyes Mata described it, “a supreme effort of the human body to survive.” But at 11:30 p.m., the captain died.

He’d been among the most popular in the FAP. A writer and thinker, always enthusiastic. As the FAP’s political chief he was invaluable from the earliest days in Cuba. He had a simple funeral and burial, where Reyes Mata described to all those present as being paralyzed with grief at his loss.

Álvarez Martínez’ career was meteoric. By 1968, he was a captain and the assistant to the G-3, Honduran Armed Forces General Staff. Later that year, he went to the Infantry Officer Advanced Course at Fort Benning, Georgia. His keen interest in counter insurgency took him back to Fort Bragg in 1969, where he attended the Special Forces Counter-Insurgency Operations course. He made major in 1971 after successfully completing the Command and General Staff course at the Superior War College in Chorrillos, Peru.

His troop commands included the General Francisco Morazán Military Academy, Chief of Operations Armed Forces General Staff, Commander of the 4th Infantry Battalion at La Ceiba, Commander of the 3rd Infantry Battalion at San Pedro Sula, and Chief of the Public Security Forces (FUSEP), during which time he attended the Combined Operations Course at the School of the Americas, Fort Gulick, Panama.

By the time Álvarez Martínez became the Commander-in-Chief of the Honduran Armed Forces in 1982, the general knew his country was in dire straits. He had Fidel Castro’s Cuba on one flank, the swiftly growing and powerful Marxist-inspired FMLN in El Salvador on the other flank and to the south, the victorious Sandinistas. Honduras was clearly in the crosshairs as the next country in Central America to be attacked. Guatemala to the north was battling the beginnings of an armed insurgency within its borders.

Operation CONDOR was a joint agreement between the southern cone countries mentioned, the U.S., and by 1982, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. It allowed for a combined and aggressive intelligence-sharing network and highly trained units with permission to conduct cross-border operations that included kidnapping and assassination. CONDOR’s goal was the utter dismantling and destruction of the subversive infrastructure regardless of liberation movement acronyms. Fire would be fought with fire.

Gustavo Adolfo Álvarez Martínez, a graduate of the U.S. Army’s Special Forces counter-insurgency course at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, approved the placement of U.S. forces in Honduras beginning in 1982. He would also support the Contra War and pushed to see Contra bases established deep inside Nicaragua. Álvarez Martínez declared total war on the Honduran guerrilla column (FAP), destroying it in a classic counter-insurgency campaign that lasted less than two months. (Author collection)

But things changed for the better with the election of Ronald Reagan as U.S. President. In short order, the Reagan Administration made it clear it would not be soft on communism anywhere in the world and specifically in Latin America.

The fall of Nicaragua to the Sandinistas–with direct support from Cuba, Vietnam, East Germany, and Russia–put all Central America at risk.

Reagan provided overt, clandestine, and covert support to Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. Discreet relationships were renewed and deepened with Argentina, Chile, Venezuela, and Brazil–all conducting so-called “dirty wars” against communist-inspired insurgencies in their own countries.

U.S. President Ronald Reagan met with General Gustavo Álvarez Martínez at the White House in 1982. In 1983, after the destruction of the FAP, Reagan presented General Alvarez with the U.S. Army’s Legion of Merit. (United States’ White House Archives)

President Reagan’s determination to stop communism dead in its tracks in Central America saw U.S. overt, clandestine, and covert aid provided to both El Salvador and Honduras. (United States White House Collection)

Degüello – “No Quarter to be Given”

By August 15th, General Alvarez had mobilized the Honduran Armed Forces to counter the now well-defined incursion of the FAP from Nicaragua. Deserters were voluntarily exchanging critical, detailed information about Reyes Mata, Comandantes “Adolfo” and “Gregorio” as well as every member of each platoon. For their cooperation, they were well-treated and their stories of being press-ganged into the FAP, forced to watch executions of their own, and all the while starving in the jungle were given wide coverage by the Honduran media.

The general had learned his lessons at Fort Bragg well.

“Argentina and Chile have agreed to provide military assistance to Honduras…Argentina agreed to provide credit terms [for] forty-five million dollars at seven percent interest [with] the first three years being no payment due. Top priority is off the shelf equipment for counter-insurgency use; and training teams (MTT) skilled in counter-insurgency operations. The first MTT has arrived in-country…Three Chileans met with the Honduran Foreign Military Sales Committee and agreed to assist Honduras in the counter-insurgency field.” – U.S. DOD, Joint Chiefs of Staff Message Center

Operation Patuca River was now well underway.

***

In the December 2022 Sentinel:

Part Three – Tracking the FAP from Tiger Island… the 2nd Ranger Battalion joins the hunt in Olancho…El Aguacate readies its holding and interrogation cells…Honduran Special Forces and the COBRAs deploy to the jungle…the “Red Empire” makes its presence known…the FAP vows not to retreat even as Daniel Ortega quietly shuts the border down so they cannot return.

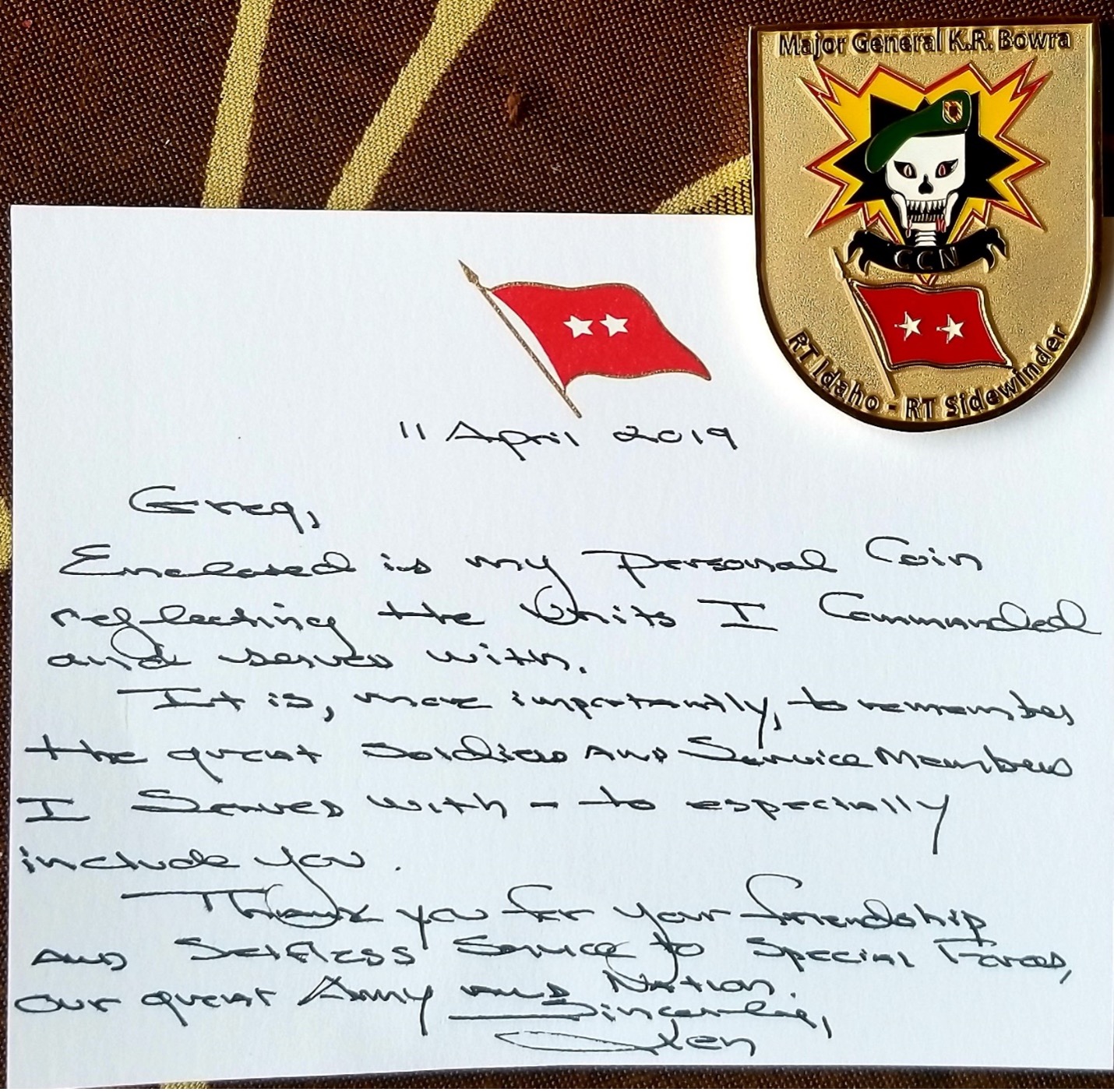

ABOUT THE AUTHOR — Greg Walker is an honorably retired “Green Beret”. During his military career he served with the 10th, 7th, 12th, and 19th Special Forces Groups (ABN). He held DIMA positions with USASFC, then under the command of Major General (ret) Kenneth Bowra, the 3rd and then the 5th Special Forces Groups (ABN). Greg’s awards and decorations include the SF Tab, two awards of the Combat Infantryman Badge, three Meritorious Service Medals, and the Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal (El Salvador / Iraq). Today he lives and writes from his home in Sisters, Oregon, with his service pup, Tommy.

Enjoyed your articles about Baez. I was stationed in Panama with the 193rd INF BDE from ’82-’85. I was in 7th SFGA from ’85-’88. Did TDY in Honduras in 1986. I knew Bill Chadwick while in Panama and Ft. Bragg. Keep up the good work!

I have been interested in this article and look forward to the next chapter. I had the honor of commanding SFODA 5 and knew SGT Baez.

Enjoyed your article. Thank you!