A DEFECTOR IN PLACE: The Strange and Terrible Saga of a Green Beret Sandinista – Part Three

By Greg Walker (ret)

USA Special Forces

"Cry 'Havoc,' and let slip the dogs of war;

On July 27, 1983, Comandante Reyes Mata gave Lieutenant “Justo Martinez” a large sum of Honduran lempiras “to purchase mules, supplies, and, especially, food”. Lt. Martinez and several other guerrillas left the base camp at Congolon for the closest town, Nueva Palestina, a three to four-day hike through the jungle on foot. It was a two-fold mission. Martinez was to establish the FAP’s presence in the town, linking it with Congolon. A similar link would then be made with Tegucigalpa, the country’s capitol city. Once accomplished the FAP’s “Internal Front” would become a reality. “We have vested in it our hope for survival,” wrote Reyes Mata in his war diary.

Lieutenant Martinez was given three days to reach Nueva Palestina, two days to accomplish their tasks, and three days to return to base camp. On July 30th, Combatant “Marvin” deserted the base camp. Leaving his weapons and equipment the guerrilla took only his watch and blanket with him as he headed back toward the Patuca River. A three-man team sent to take him into custody could not catch the fleeing Honduran. “Marvin” was the first of what would become a relentless tide of desertions over the next six weeks.

On the morning of August 2nd, “Miguel”, “Mairena”, and “Renecito” had slipped away taking their weapons and equipment. This to discourage any pursuit by the FAP. Unknown to Reyes Mata was that two deserters had reached the town of Catacamas and turned themselves in to the FUSEP, or National Police. They shared all they knew with the police, who in turn notified the Honduran Army. General Gustavo Alvarez, head of the Armed Forces, was furious and with good reason.

On July 19th, in Nicaragua, Daniel Ortega had proposed a six-point peace plan with Honduras tied to the Contra war. Now, General Alvarez was learning that on this very same date with the support and blessings of the Cubans and Sandinistas, a heavily armed and well-trained Marxist column had crossed the Coco River. Further, it was led by Dr. Jose Reyes Mata and with two Nicaraguan combat advisers with him. It was a betrayal the general would not abide.

“Those” included not only Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua but Fidel Castro in Cuba. Castro provided a year’s training for the new guerrilla army in 1982 at the Cuban Army’s Special Troops training base at Pinar del Rio, located just 90 minutes from Havana’s Jose Marti Airport.

By now, the 96-person column–brought back from Cuba in ones and twos–was assembled in a safe compound outside of Managua. Security conditions were strict. No leaving the compound, no female visitors, no contact with families, and no money. Individuals who deserted were captured and immediately put into a Sandinista prison. Reyes Mata didn’t see this red flag for what it was: the unhappiness and dissatisfaction of some people who didn’t “volunteer” to be guerrillas in his revolution but rather press-ganged into the movement with promises of civilian occupation training in either Managua or Havana.

Reyes Mata’s recruiting efforts occurred in Honduras’ Olancho province by local Revolutionary Party of the Central American Workers (PRTC) Honduran agents, as well as “guerrilla priests,” many of these Jesuits. In a 1984 Miami Herald story (“Deserters Say Foreigners Fight for the Sandinistas”, Guy Gugliotta), Arnulfo Montoya Madariaga, then 35, described his recruitment in 1981. A campesino with a plot of land and seven children, he was recruited by “a French priest at his farm outside Danlí in southern Honduras.”

By September 21, 1983, 23 FAP combatants deserted, were captured, or turned themselves in to Honduran forces. The first desertion took place within two weeks of the FAP July crossing the Coco River in platoon-size elements. By the end of August, deserters provided the Hondurans and Americans with detailed descriptions regarding the platoons, personnel, leadership, weapons, communications, and the logistical support for the column. “Disgruntled employees” and empty stomachs marked the beginning of the end for Baez & Company

Honduras is “peaceful and friendly”

The FAP was combat-ready. The column’s members were broken down into smaller groups of combatants and farmed out to the IWB of the EPS for another six months of fight training the Contras. On January 11, 1983, FAP commanders “LaPorta” and “Marcos” gave detailed reports about ambushing “an entire enemy company, which in its confused flight, left behind weapons, supplies, and a large quantity of rations.” The FAP continued working alongside the EPS until final preparations began for their infiltration into Honduras in mid-July.

“Before leaving, I explained to everyone that our movement must not be noticed by the enemy, and that secrecy, precaution, silence, and initiative would be our principal weapons…based on the information obtained from the enemy which I checked, they were waiting for us, to liquidate us and the daring plan for a march, flanked by enemy [Contra] camps. Everything seemed uncertain.” – from the captured war diary of Dr. José Reyes Mata (Comandante Pablo Mendoza), July 15, 1983.

Fidel Castro and Daniel Ortega (Credit: LatinAmericaStudies.org)

On August 4th, the Honduran Army arrived in Nueva Palestina and established its forward operating base (FOB). Lieutenant Justo Martinez and his resupply team had just arrived, as well. In his diary entry of August 6th, Reyes Mata offers “…we complete 10 days without food…We are all waiting anxiously for him…”. Two days earlier Reyes Mata had personally executed Combatant “El Paisa”, whose true name was Juan Ortiz. Ortiz was accused of planning to assassinate Reyes Mata and inciting those who had deserted to have done so. A swift jungle trial was held, and Ortiz killed in front of all those other guerrillas present. The execution did not stop the desertions. In fact, they would increase with those surrendering providing even more information about the FAP.

By now the column had lost six of its original 96 members to desertion, capture, and execution. Still, Reyes Mena believed he had won a “great political victory”. He’d also lost four M16s, 2 grenades, and roughly 1500 rounds of ammunition and yet the FAP had not engaged in a single armed engagement.

In an August 30th U.S. Department of Defense message to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, provided by the Honduran G-2 and U.S. Defense Attaché, a nine-page report gave the names and position of each guerrilla in the column. In addition, the commanders, sub-commanders, and political officers for each of the four platoons were identified. The true names and alias of the deserters to date and the members of the FAP support staff to include “Comandante Adolfo”, or David Arturo Baez Cruz and “Gregorio” were noted; Finally, the battle plan for the column was revealed as it sought to open separate fronts in Honduras.

The deserters had described radio communications capable of reaching Nicaragua and “other countries”. Deserter Enoc Benigno told his interrogators the radio had to be used with a dipole antenna put as high as possible in a tree “for better signal propagation.” One power source was a car battery and the other a portable generator operated by a mechanical pedal. Comandante “Fidel”, leader of the Third Platoon, held all the codes and frequencies. As he had forgotten to pack an extra battery the generator had become the sole source of power for communications. Communication security was poor. Transmissions were daily and always occurred at 0900 and 1600 Hours and were 30 minutes each in duration.

In short order the Honduran Military, working in concert with the U.S. Military and the CIA, began intercepting guerrilla radio traffic. Using the U.S. operated clandestine radio communications intercept sites atop Tiger Island in the nearby Gulf of Fonseca, and another located inland between San Lorenzo and Tegucigalpa, General Alvarez’s Special Forces task force begin placing blocking forces from Honduran infantry units at key trailheads, villages, towns, and roadways in Olancho Province. Major Leonel Luque was assigned by General Alvarez as the task force commander. Leonel Luque possessed a Military Police background and had attended the School of the Americas in Panama. He was also an important liaison with the Contra effort on the Honduran border and known for his ruthlessness in dealing with subversives.

Reyes Mata allowed for just eight days for Justo Martinez to return to Congolon with supplies. The situation at the base camp was deteriorating swiftly. Listening to their own radio the guerrillas discovered they’d been compromised by the deserters and the Army’s response. Reyes Mata ordered the camp struck and the column split in two. His group would remain in the Nueva Palestina area, the other group now commanded by Comandante Serapio Romero (Frente Oriental) would begin its trek to the Catacamas Mountains. “Gregorio” would travel with this group. “Adolfo”/Baez would remain with Reyes Mata and combatant James “Lupe” Carney. Serapio’s unit departed 48-hours before Reyes Mata. Serapio would bivouac at a pre-determined location and allow the slower moving Reyes Mata to catch up before they parted for good. It was determined the FAP would not return to Nicaragua. It would remain in pursuit of its mission to wage war in Honduras.

As the starving band started down the trail, they were joined by combatant Raul Felipe Calix. “[He] appeared, completely beaten, but all right,” wrote Reyes Mata. “They had left him alive.” Although his diary does not identify the other guerrillas that were with LT Martinez it is reasonable to presume Felipe Calix was one of these. And had managed to escape the Army in Nueva Palestina to warn the FAP they were being hunted.

Rangers Lead the Way!

“…the U.S. Southern Command admits 150 American troops, most of them Army Rangers from Fort Lewis, Washington, were parachuted in Olancho on August 5th. They stayed until August 16, engaging in what the Pentagon called ‘a simulated counter-insurgency operation’ with Honduran forces. August 5th was the day after the Honduran Army’s Patuca Task Force arrived in Olancho on its real counter-insurgency mission.” – The Nation, “The Mysterious Death of Fr. Carney,” August 4-11, 1984

The Honduran Special Forces Squadron was originally trained in La Venta, Honduras, by a U.S. Special Forces operational detachment from the 3/7th SFG(A) then stationed in Panama. La Venta, roughly twenty miles from Tegucigalpa, was the headquarters for both the “TIGERS” squadron as well as the COBRAS. The COBRAS were trained by a separate 40-man mobile training team recruited at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. Both efforts took place in 1982. The Green Berets responsible for the COBRAS grew their hair out, wore civilian clothing, and arrived in Honduras completely “sterile”. Meaning no dog tags or any other U.S. military identification (the same precautions David Baez had used before crossing the Coco River with the FAP).

Both the Tigers and the Cobras were trained in counter-insurgency, counter-terrorist and unconventional warfare strategies, tactics, and techniques. These included sniper employment, special weapons, hand to hand combat, raids, ambushes, the clearing of airplanes and buildings, and Intelligence collection/assessment. At times individual instructors with unique specialty skills such as photography and demolitions were brought in. Both MTTs delivered a well-trained 120-man Honduran Special Forces squadron owned by the Army and a 40-man Urban Operations Command, or Hostage Rescue Force (HRF) that fell under FUSEP. Both these elite units were under the direct command of General Gustavo Alvarez, Chief of the Armed Forces.

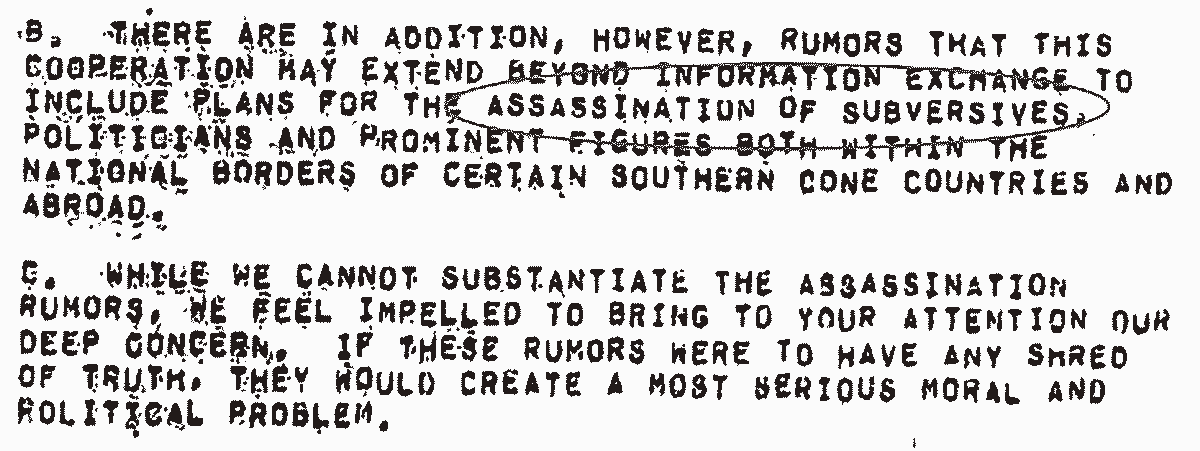

Working in conjunction with the Tigers and Cobras were the military intelligence teams of Battalion 316. B-316 was the direct result of General Alvarez’s long time professional and personal relationships with the military in Argentina. That country’s armed forces had been conducting a “dirty war” against communist influence and objectives for over five years. The larger operation began in 1976 and was a collaboration between Brazil, Uruguay, Argentina, Chile, and Paraguay. CONDOR allowed for extra ordinary cross border cooperation between Intelligence services and special units. Kidnapping, torture, assassination, and “disappearing” suspects by dropping their sometimes still living but most often dead corpses from fixed and rotary wing aircraft was sanctioned.

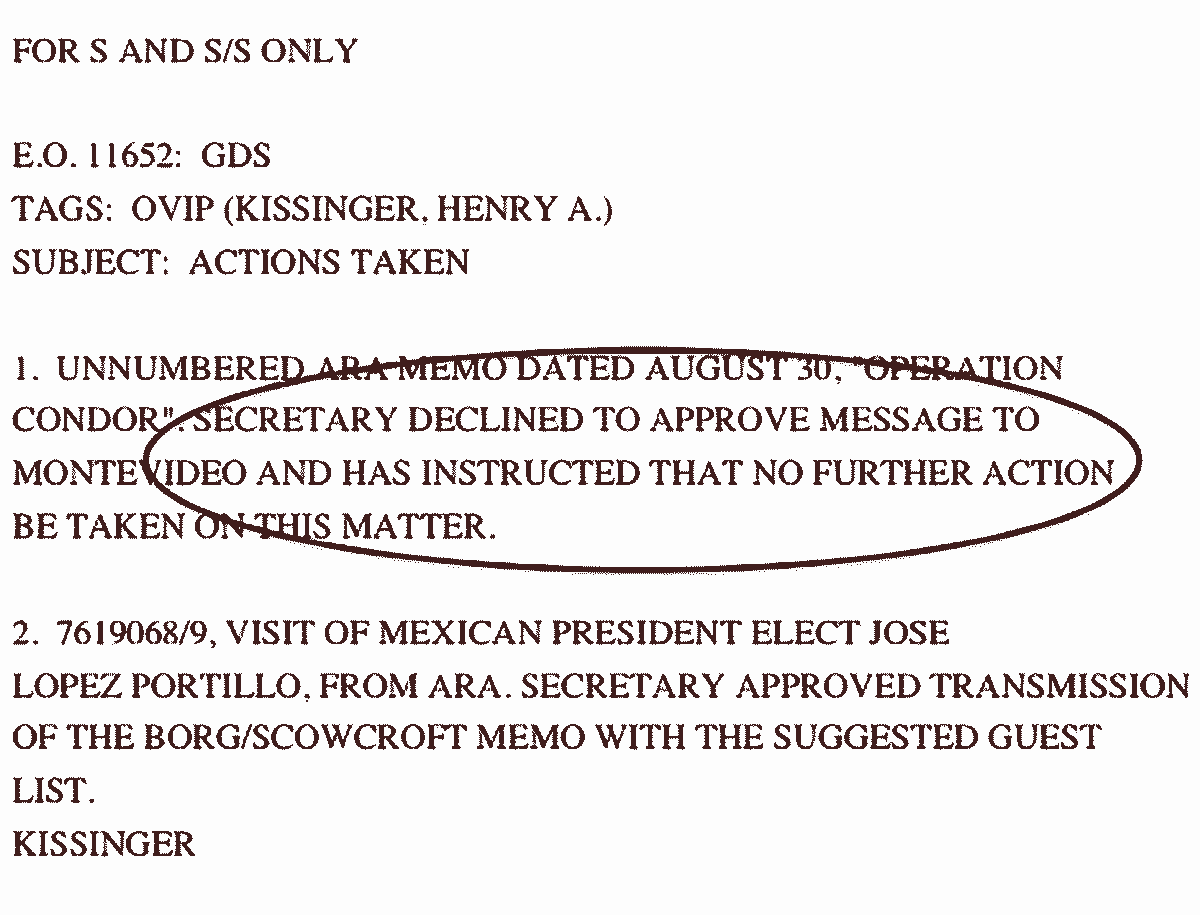

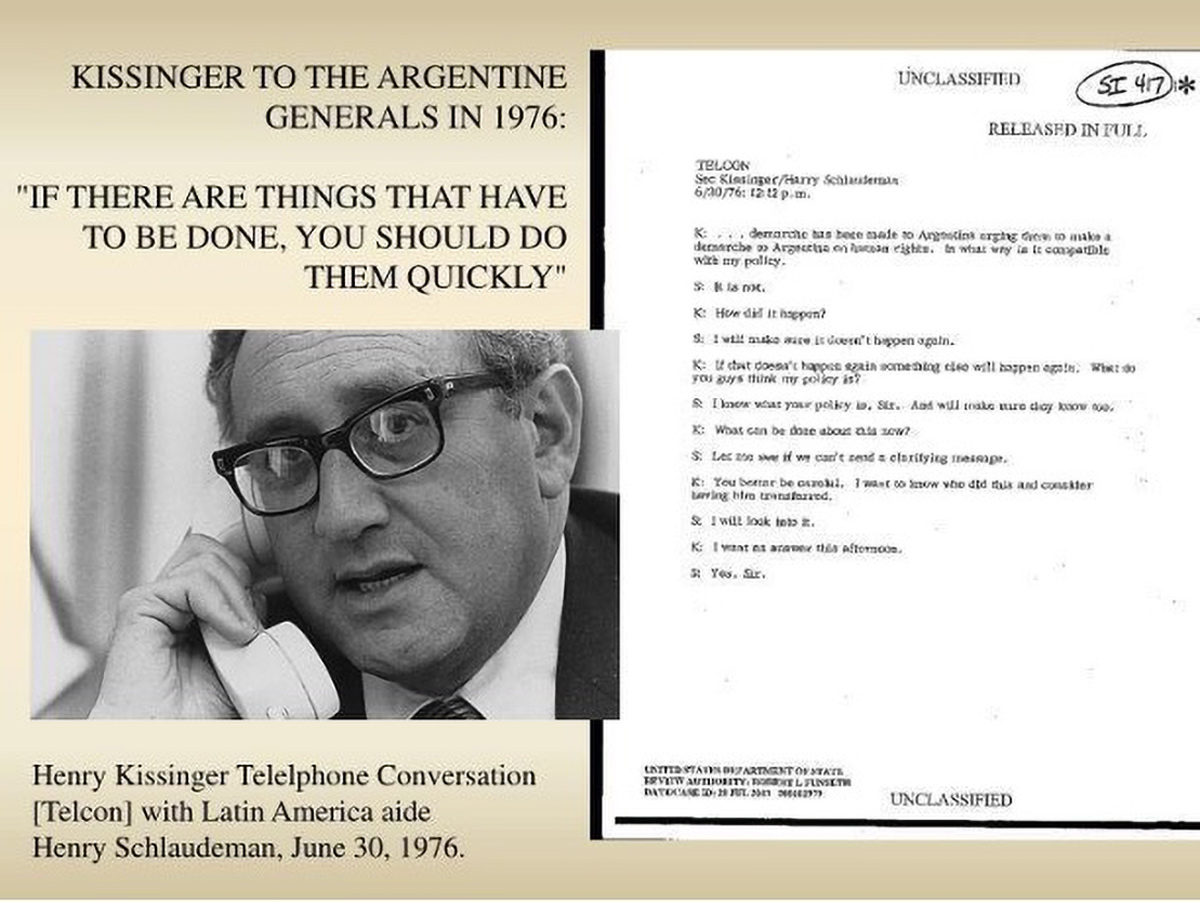

The United States under both President Carter (1977-1981) and Ronald Reagan (1981-1989) were fully aware of CONDOR and both encouraged and resourced it. An August 1976 cable to the State Department from U.S. diplomats in Latin America raised early and grave concerns regarding CONDOR being far more than simply intelligence gathering and sharing (Figure 1). Secretary of State Henry Kissinger was at first cautious in his response, but within days sent the subtle message that no further oppositional action was to be taken regarding CONDOR and its goals/objectives by U.S. State (Figure 2).

Although CONDOR was officially shut down in Argentina and that country’s direct support of subject matter experts in interrogation, torture, and assassination withdrawn from supporting U.S. efforts in Central America, the over-arching years of collaboration and financial support as managed by the Central Intelligence Agency to its allies in Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala had created units such as Battalion 316, a mirror image of its parent, Battalion 601, in Argentina.

Operation CONDOR, as was formally known as, was supported by U.S. assets and resources. The end game was the destruction of any and all suspected or proven communist movements in both the southern cone (South America) and Central American countries. CONDOR grew out of Cuba’s continued and blatant efforts to destabilize Latin America, with Che in Bolivia (and a concurrent Cuban sponsored effort in Argentina at the same time) the basis for such a program. When Nicaragua fell to the Internationalist Marxist revolutionaries under the Sandinista banner, and although by 1982/1983 Operation CONDOR was being shut down and war crimes trials for its creators and participants on the horizon, El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala imported CONDOR veterans and their techniques to counter the myriad of Marxist armed groups such as the FMLN, FSLN, and PRTC.

In all fairness the Sandinistas, finding themselves facing the Contras with their U.S. backing, likewise employed former CONDOR specialists for the same if not opposing ideological purposes

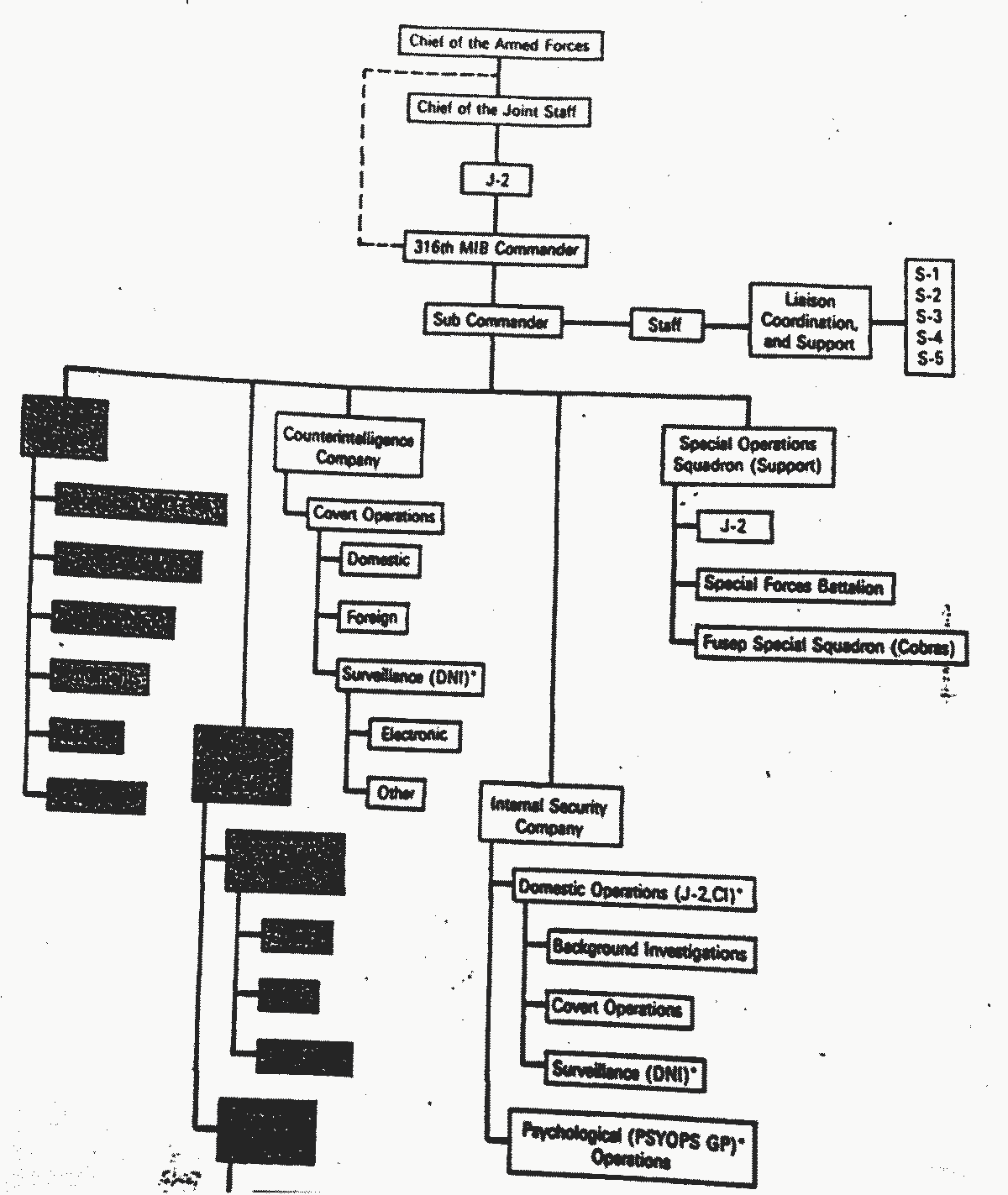

Alvarez wanted his own counter-part unit to Argentina’s feared Battalion 601. And he got it. The 316 Military Intelligence Battalion’s commander reported directly to Alvarez, and was on the same command wiring diagram as the Special Forces Squadron and COBRAS. B-316 oversaw or ran counter-intelligence operations, covert and clandestine operations, domestic and foreign operations, electronic and “other” surveillance efforts. It also had a hand in Psychological Operations although those were run by a separate unit. The “iron fist” for B-316 were the Tigers and the Cobras. When the FAP crossed the Coco River and was discovered, as well as Daniel Ortega’s diplomatic treachery, the stage was set for all three units to be put to the test…and with U.S. knowledge, support, assets, and resources.

(Credit: Alchetron.org)

Command, Control, and Missions for BN 316, the HSF, and FUSEP

“The Argentines came in first, and they taught how to disappear people. The United States made them more efficient. The Americans…brought the equipment. They gave the training in the United States, and they brought agents here to provide some training in Honduras. They taught us interrogation techniques.” – Lt. Oscar Alvarez, Honduran Special Forces, nephew of General Gustavo Alvarez

Death sentence

“In accordance with the International Rules of Land Warfare, had [the FAP] established a shadow government, held a piece of territory and governed it, wore uniforms and had an established legal system, they would have received protection under the Geneva Convention. Reyes Mata would have known this.” – MSG (ret) Leamon Ratterree, 3/7thSpecial Forces Group (A)r

Reyes Mata and Serapio Romero went over their final plans. Reyes Mata and his group would continue toward Nueva Palestina and attempt to refit and resupply. Comandante Serapio would take his group, the fittest of the remaining FAP, and move along the Patuca River toward the Catacamas Mountains and, once there, strike inland toward the Capacan Mountain Range and the Tinto River. The guerrillas continued to forage in the jungle, and although their food was minimal, they were blessed in having an abundance of water available. A human being in the circumstances the FAP guerrillas were in would die within 48-72 hours without water. However, the sporadic rainfall and the Patuca River with its feeder streams ensured their survival.

What neither commander knew was just how enormous the manpower and resources of the Honduran and U.S. armies were.

On August 28th, with the help of signal intercepts, overflights of specially equipped U.S. Air Force C-130 surveillance aircraft flying out of Howard Air Force Base in Panama, and the provision of five U.S. Black Hawk helicopters from the 101st ABN Division to move Honduran forces swiftly, Reyes Mata’s group was discovered, then pinpointed. Honduran Special Forces were inserted and in short order contacted the guerrillas.

The ensuing firefight saw the guerrillas break down into smaller groups to escape and evade their pursuers. Reyes Mata, David Baez, and James Carney stayed together, working their way toward Nueva Palestina where they hoped to find help. In an intelligence report declassified and released on June 29, 2010, mention is made of a pistol belonging to James Carney being turned over to the HRF by two captured guerrillas. The pistol was in turn given to the Honduran C2 as evidence. By now all the guerrillas were severely undernourished and down to skin and bones. Their uniforms were filthy, torn, wet, and hanging from each man’s body like a hellish shroud.

On September 4th, it was reported the HSF had surrounded and captured the three men in the vicinity of Arenas Blancas and Cerro Azul. They were within a kilometer of reaching a well-traveled road with only a small stream to cross barring their way.

On September 5th, Major Leonel Luque established a second task force launch site at Rio Tinto to support the hunt for Serapio Romero’s guerrilla band. U.S. Black Hawk helicopters began moving elements of the Honduran 5th Infantry to blocking points, as well as at least 50 HSF troopers to be inserted on the band’s trail as it traveled along the Patuca River’s bank. Contra patrols, tracking the guerrillas as well, were in radio communications with Nueva Palestinia and now Rio Tinto, and were likewise eager to locate the band. Overhead, the Black Hawks, having unloaded their troops, began flying aerial reconnaissance in support of the ground operation and acting as communication relay platforms given the dense jungle and mountainous terrain.

On September 7th, contact was finally made, and the first firefight occurred along the Wasparasni River near Salto de al Mona. Although the guerrillas broke contact, the hunt was now fully engaged. A second firefight broke out on the 11th with three guerrillas captured (Castro, Moncada, and Duarte). Serapio had ordered the remaining guerrillas to split into three smaller groups. Sensing victory was at hand, General Alvarez Martinez ordered all available forces to engage. Alvarez made it clear the first 23 deserters had left the FAP on their own. This was in response to, in great part, the multimedia public affairs effort utilizing the deserters to urge their comrades still in the jungle to give up. From this point onward, only prisoners would be taken.

On September 16th, near Culmi Mountain, government forces again clashed with the FAP. There were casualties on both sides. The remaining guerrillas were now heading for Mt. Capapan. If they could reach the mountain they could hunker down and wait for an opportunity to slip down to the well-used improved road and escape by vehicle. Unsuspected by the guerrillas was the major task force headquarters at Nueva Palestina and the HRF launch sites at Rio Tinto, and now Dulce Nombre de Culmi.

On September 17th, the last confirmed firefight between the FAP and the Honduran Army took place near the Capapan Mountain. All captured guerrillas beginning on August 28thwere now held at the clandestine U.S. / Contra air base known as El Aguacate located midway between the town of Catacamas and Rio Tinto just off the main highway.

An outlaw airstrip in the badlands on the border

“Two American enlisted men told the reporters that they could not enter without the Hondurans’ permission. Unlike Americans at other bases in Honduras, the men were armed with automatic rifles instead of sidearms. Asked if there were any Nicaraguan rebels at the base, one of the Americans said, ‘We were told they’re supposed to be the good guys, and not to shoot at them.”’ – “At a Honduras Base, More Questions than Answers,” NY Times, December 14, 1983

The CIA’s clandestine airfield in southern Honduras provided safe haven and resupply for the U.S. backed Contra forces operating in Nicaragua. The core leadership and most accomplished Contra fighters came from the “Black Berets”, an 80-man commando unit trained and led by Vietnam veteran Michael D. Echanis. When President Anastasio Somoza fled Nicaragua, the “Black Berets” commandeered small boats and after crossing the Gulf of Fonseca, surrendered themselves and their weapons to the Salvadoran military/CIA station at La Union, El Salvador. Echanis was one of three American contractors killed in September 1978 when the private aircraft they were flying in, piloted by Nicaraguan general Ivan Alegrett, exploded over Lake Nicaragua. The kill order came from the highest levels of the Somoza government as Alegrett was suspected of encouraging a coup against his long time friend, President Somoza. (Credit: ADST)

El Aguacate, with its 8,000-foot airstrip, was built with misappropriated U.S. tax money using U.S. armed services personnel, equipment, and resources. Signed off on by General Gustavo Alvarez, the base was primarily used to house, train, and equip Contra fighters with the FDN. Facilities included a field hospital and several cemeteries for Contra dead. (Credit: ElPulso.hn)

The year 1975 was a dismal one for Special Forces. With the end of the war in Vietnam, the United States Army was restructuring itself. Special Forces, which had seen rapid expansion during the war, was now on the chopping block. The 5th Special Forces Group (A) was among the first to see its ranks culled by both involuntary separations from service and normal attrition. The 8th Group, best known for its significant contribution to seeing Che Guevara run to ground in Bolivia in 1967, was to be deactivated. It was only through clever politicking and the documented rapid expansion of communism and Marxist-inspired revolution in Latin America that the 8th was honorably transitioned and became the 3rd Battalion, 7th Special Forces Group (A) in Panama.

The attrition of seasoned Latin American veterans wearing the green beret to include their language and cultural capabilities as the 8th Group’s colors were lowered demanded an influx of, among other skills, Spanish language-qualified speakers. Special Forces in Panama not only conducted mobile training teams throughout Central and South America but also provided military subject matter experts as instructors for the School of Americas (SOA), also located at Fort Gulick.

In March 1976, Sgt. David Baez found himself on leave back to Panama for this very reason. He would be promoted to Staff Sergeant, E-6, that June. Now he was an experienced non-commissioned officer with invaluable experience from his tour with 10th Group in unconventional warfare to include setting up and running clandestine and covert urban guerrilla cells. His tradecraft training with practical field exercises like Flintlock included surveillance techniques, lock-picking, hard and soft target assessments, demolitions, infiltration and exfiltration techniques, recruiting and developing informants, as well as counter-guerrilla operations.

All officers are to have blood on their hands!” – GRAL Gustavo Alvarez Martinez upon ordering the execution of the remaining FAP guerrillas being held at El Aguacate Air Base

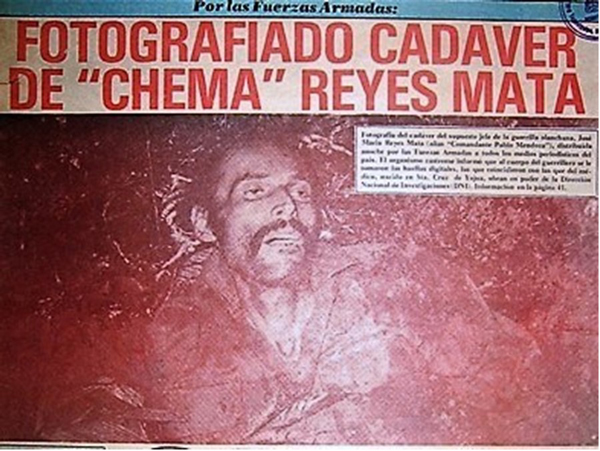

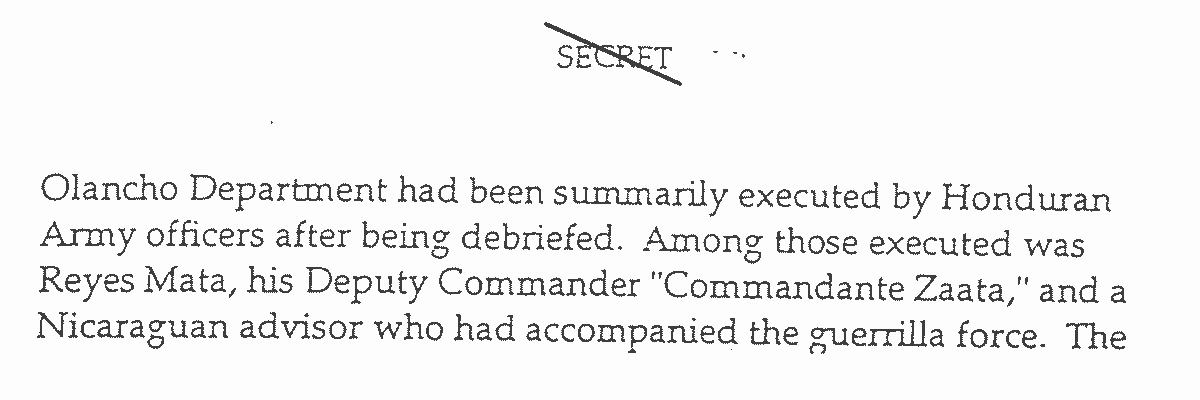

Upon his arrival at Fort Gulick, the young sergeant swiftly obtained On or about September 18th, roughly 36 FAP prisoners being held at El Aguacate were summarily executed. Dr. Reyes Mata was personally shot by a senior task force officer who has long since been identified by the CIA inspector general’s 1997 report, although that officer’s name is redacted. However, additional references from other sources strongly point toward the task force commander, Major Leonel Luque, as being the FAP commander’s executioner.

A contra graveyard was discovered long after the base was abandoned and exhumation of those buried there revealed the dead’s remains — https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UXwOCnYzoz8

In 1984, two officers—one American and the other Honduran—met at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. They were preparing to attend the Special Forces Qualification Course together. Both were Ranger qualified, the Honduran having just completed Ranger School at Fort Benning, Georgia. The American, John McMullen, would go on to honorably retire from the Army as a full colonel. Along the way he would serve with distinction in El Salvador as well as in Honduras.

The Honduran officer, related as he was to General Alvarez, possessed firsthand knowledge of Operation Patuca River, to include the fate of those insurgents executed at El Aguacate. As they went through the Special Forces course together, he began to relate what he knew. “We just talked about it,” recalled Colonel McMullen. “I mostly listened as I was surprised to learn about one of our own, David Baez, being involved as he was.”

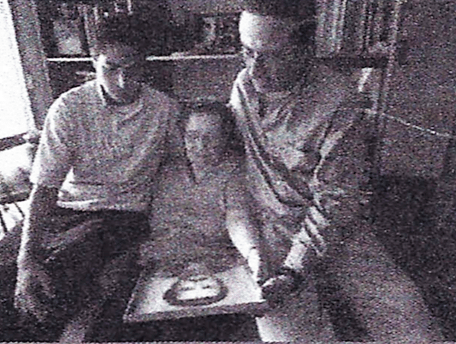

During one discussion the Honduran officer showed the American two photographs. In each was a captured FAP insurgent sitting on a bunk. “They looked like concentration camp victims,” McMullen recalled. The Honduran officer told him that the deserters were well treated and fed, but they learned not to give them all the food they wanted right away. “One of the deserters in the photos actually died because he ate too much, too fast. The other became very sick but pulled through,” offered the retired Special Forces officer.

The Honduran officer described what took place after his uncle ordered the executions to occur at El Aguacate.

All the prisoners had been interrogated by professionals from Battalion 316. It was important to learn as much as possible about the now-failed insurgency, especially whether there were other FAP units in Honduras—urban commando units and logistical personnel, specifically. Everything about how they were recruited, when, and where needed to be learned and compared to information given earlier by the first 23 deserters. CinC Alvarez specifically wanted anything and everything that connected both Cuba and Nicaragua to the FAP incursion.

During the interrogations former Green Beret David Baez confirmed his identity as did James Carney. A phone call was made to the U.S. embassy. The confirmed capture of the two Americans was relayed to the ambassador, John Negroponte. The Honduran military wanted to know what the disposition of the gringos was to be given the execution command from Alvarez. According to the retired Special Forces Colonel, whomever was on the other end of the phone at the embassy basically said, “Get rid of them.”

In his 1983 report on human rights in Honduras as prepared for the U.S. Congress, Ambassador John Negroponte (center), nicknamed “The Black Prince” by U.S. Special Forces, sanitized the document to the point of parody, as these excerpts from the 1983 edition illustrate: “There are no political prisoners in Honduras”; habeas corpus “appears to be standard practice”; “access to prisoners is generally not a problem for relatives, attorneys, consular officers or international humanitarian organizations”; “sanctity of the home is guaranteed by the Constitution and generally observed.” (Credit: NY Books.com)

“All of the guerrillas were taken outside and lined up with their backs toward the jungle,” John McMullen remembers. The Honduran enlisted men were not to take part in the executions and were sent elsewhere. Only the Honduran Special Forces officers were ordered to participate. Reyes Mata was shot. His body would be photographed in two separate poses, both images provided to the Honduran media as proof of his death. Because David Baez had confirmed being an American “Green Beret,” it was decided a young Honduran captain who had recently graduated the U.S. Special Forces qualification course at Fort Bragg would do the honors. Baez was described as having been shot point-blank in the chest by this officer. James Carney was likewise shot.

“He [the Honduran officer relating these details] told me at first the officers were using rifles to shoot the prisoners. But there were so many of them and the rifles became cumbersome, so they finished the executions using their pistols,” McMullen stated.

His account coincides with the CIA IG’s report where on page 80, although heavily redacted, the document describes “three or four” of the guerrillas having been flown to Tegucigalpa where they met in private with General Alvarez. They were then returned to El Aguacate and the following instructions given:

![11_CIA-instructions1-1200px 220. (S) [crossed out in image] After approximately 20 days of being in the field, (contents redacted) and three or four guerrillas to Tegucigalpa. (Redacted contents) met with CINC Alvarez privately. After the meeting (contents redacted) and the guerrillas headed back to Nueva Palestinian a helicopter. (Contents redacted) told (contents redacted) the "We have to make them disappear." (Contents redacted) said that the guerrillas were to "die in combat or be executed after we get information from them and in a place they can't be found." Only officers were to be involved in carrying out the executions and each officer had to participate so that would not disclose their actions. (Contents redacted) an individual - (contents redacted) was given overall responsibility by (contents redacted) for ensuring that the executions were performed by each officer. 80 (page number) SECRET (crossed out in image)](https://www.specialforces78.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/11_CIA-instructions1-1200px.png)

It can be reasonably presumed the “three or four guerrillas” brought to meet with CinC Alvarez were Comandante Reyes Mata, Comandante Felipe Zapata (2nd in command of the FAP), Comandante David Baez, and Padre cum Combatant James Carney. The 1997 CIA report again confirms having identified the officer who shot the guerrilla leader, though his name is redacted.

![12_CIA-instructions2-1200px 311. (S) [crossed out in image] provided an (contents redacted) officer with information relating to the Olancho Operation indicating that (contents redacted) had shot insurgent leader Reyes Mata with a service pistol after his capture and CINC Alvarez had probably been consulted. This information was sent for informational purposes (contents redacted) to numerous organizations, (contents redacted). However, it was never disseminated as an intelligence report. 109 (page number) SECRET (crossed out in image)](https://www.specialforces78.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/12_CIA-instructions2-1200px.png)

The report also affirms the U.S. ambassador and embassy took a “hands-off” approach to the entire affair and why.

![13_CIA-instructions3-1200px 337. (S)[crosssed out in image] (Contents redacted) believes that (contents redacted) reporting did not receive fair treatment from components within the Embassy, to include (contents redacted) personnel. He recalls that (content redacted) comments on (contents redacted) reporting, in most instances, were merely a mirror of State's negative sentiments. (Contents redacted) recalls a discussion with (contents redacted) circa 1983 wherein the latter indicated unspecified individuals at the Embassy did not want information concerning human rights abuses during the Olancho Operation to be disseminated because it was viewed as an internal Honduran matter.](https://www.specialforces78.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/13_CIA-instructions3-1200px.png)

David Baez, identified in the CIA report, is also confirmed to have been captured and then executed at El Aguacate in this extract.

No fallen comrade left behind

“I am hoping that we can bring some closure to David’s death and give him a decent burial in his home country or here in the USA.” – Walter Cargile (ret), USA Special Forces

Word of Baez’s execution in Honduras spread swiftly throughout the 3/7th, his last Special Forces assignment. In 2009, Bob S. Senseney, who served as an AST with Baez in 1979-1980, told journalist Juan O. Tamayo that Baez was captured alive and then executed by Honduran Army officers. Master Sergeant (ret) Angel Chamizo, one of the most respected and experienced Special Forces senior non-commissioned officers at 3/7, likewise told Tamayo that, in 1983, at the Sheraton Hotel in El Salvador, two Honduran officers spoke with him about Baez. “They told me that Dave Baez was captured and then executed. I specifically recall them telling me that the execution order came from higher. Word about Dave Baez being killed was already going around SF circles.”

Chief Warrant Officer (ret) Don Kelly, in El Salvador at the time, spoke with a fellow Green Beret who was in the area in Honduras when Baez was executed. Kelly recalls being told that Baez and seven others, “all very skinny,” were captured and later killed.

The consistent presence of Special Forces operators from 3/7th in Honduras before, during, and after Operation Patuca River is not surprising. Charlie Company, 3/7th, had for some time been identified and trained as the battalion’s CIF, or commander’s in-extremis force for Latin America. Despite the existence of Detachment Delta since late 1977, it was understood the counterterrorism unit could not be everywhere all the time should a terrorist action occur. CIFs were stood up in Special Forces in each battalion to meet the specialized needs for responding to such threats. Training was conducted both locally within the group or battalion setting and at the SOT school at Mott Lake at Fort Bragg. “Charlie Companies” reflected a high degree of experience, expertise, and capability wherever they were located.

For example, in 1979, when the Sandinista Army was on the outskirts of Managua, Nicaragua, C-3-7 was alerted to assist in the expected evacuation of the U.S. embassy there. The CIF prepared to parachute into the nearby soccer stadium, move to the embassy, secure it, and “assist a NEO of U.S. and selected local nationals” under OPLAN 79-100. The company stood by for five days at Howard Air Force Base in Panama until ordered to stand down. However, had the CIF executed its mission it would have assisted embassy personnel and others being flown by helicopter out to the waiting USS Belleau Wood (LHA-3) then off the coast of Nicaragua.

To his Special Forces brothers, Dave Baez, regardless of motivation, remains a fallen comrade not to be left behind.

Welcome to the jungle

“They loaded the bodies onto helicopters and flew them out over the jungle where they dumped them.” – Colonel (ret) John McMullen, USA Special Forces

Oscar Alvarez was the first Honduran officer to graduate the U.S. Special Forces Qualification Course. He attended the course in 1984, along with then Captain, John McMullen. (Credit: InsightCrime.org)

In the spring of 1984, John McMullen and then Lt Oscar Alvarez, nephew to General Gustavo Alvarez, attended SFQC at Fort Bragg together.

They became good friends.

At one point Lt. Alvarez, who had completed US Ranger School just before coming to Bragg, talked with John about what took place during Operation Patuca, to include the fate of the 40 or so FAP guerrillas who were captured and brought to the El Aguacate air base near the NIC border with Honduras.

Everything Colonel McMullen describes of that conversation regarding the conduct of the OP matches the historical and documented record.

To include Alvarez showing John two pictures he had of deserters who surrendered early on and were starving. As John described, the two were well cared for (part of the early PSYOP plan) and provided food and a safe place to rest and recover. However, one of the deserters in the photos ate too much too fast too soon (His captors didn’t know the potential of death by feeding them like this) and he, indeed, died. The other became very ill but was treated and lived.

The roughly 40 guerrillas captured, to include Reyes Mata, Baez, and Carney, were gathered together at the air base. The first 23 deserters were granted amnesty. The remainder, per General Alvarez, were ordered to be shot as they were deemed not able to be “rehabilitated”.

Reyes Mata, Baez, and Carney were all properly identified. A call was made to the US embassy regarding Baez and Carney as their captors were unsure if they still held US citizenship and what to do with them. The response was in short “Get rid of them”.

Carney had renounced his U.S. citizenship and Honduras had revoked his Honduran citizenship when his actions in the country were deemed a security threat. He ended up in Nicaragua until the incursion. Baez’s U.S. citizenship status was unknown after his defection to Nicaragua. But his U.S SF background and what he’d been doing in counter-contra operations made him, apparently, an easy decision point, citizenship or otherwise.

SOG Legend refutes former DELTA operator claim to have killed Baez

Major General (ret) Eldon Bargewell (August 13, 1947 – April 29, 2019) and I first met in 1979 at Fort Benning, Georgia. We would go on to become good friends up until his untimely passing in 2019.

I asked MG Bargewell about claims made in writing by a long-retired DELTA operator that he (the DELTA commando) had shot and killed David Baez during an operation in Honduras.

“Yes. I was [his] troop and Squadron Cdr from mid 81-84. I never heard of D guys, particularly a troop from my Squadron ever doing anything like this. His claim to have roomed with Baez at [DELTA]selection in 79-80 may be technically correct since candidates slept in open bays.” – January 22, 2019

“Firstly. Thanks for all you’ve done for veterans. You have been one of the guiding forces in efforts to improve Vets care in the Pacific Northwest. Before I answer – In what month and year did this Baez incident take place?” — General Eldon Bargewell, January 19, 2019

Reyes Mata’s fate was a given

All 40 guerrillas were lined up outside with their backs facing the jungle. General Alvarez’s order was that they be executed and “disappeared”. All officers were to participate directly and “have blood on their hands”.

Reyes Mata was shot by the ranking Honduran officer on scene, very possibly from Battalion 316. Carney was shot by another Honduran SF officer. Baez was shot in the chest with a rifle by the 1st Honduran officer to graduate U.S. Special Forces Qualification Course (SFQC), then Lieutenant Oscar Alvarez. This, specifically, because Baez was seen to have dishonored his “Green Beret” brothers. Many Honduran officers had been trained by or attended courses at Fort Bragg, so it was deemed fitting he be executed by an SF graduate and officer.

John recalled Lt Alvarez describing the mass execution being finished with pistols. All the bodies were then loaded on Blackhawk helos and flown over the nearby Honduran/Nicaraguan border. They were then thrown out over the triple canopy jungle.

Message: “Don’t come across the border – Death awaits you”.

The long-preferred Condor method of making bodies “disappear” was to use aircraft to fly the corpses out over the ocean, the jungle, or mountains and dump them from altitude. This same approach was used by right-wing death squads in El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala in the 1980s thanks to Condor instructors from Argentina and Chile.

According to then Lieutenant Alvarez, the order from his uncle was to “return them to the jungle.” “Them” included Reyes Mata’s, David Baez’s, and James Carney’s corpses. The bodies of all those executed at El Aguacate that day were dutifully loaded onto the waiting helicopters, which then flew the 100 kilometers from the base to the Honduran-Nicaraguan border. Crossing over into Nicaraguan air space, the helos moved farther inland and began dumping their loads over the thick triple-canopy jungle below.

In the years since there have been many rumors, myths, and outright lies about the fate of the FAP, especially Reyes Mata, Carney, and Baez. In August 1999, based on information and discoveries made on the now-abandoned air base at El Aguacate, forensic teams conducted digs at four abandoned cemeteries located on the base. The Honduran government offered that there was a better-than-average chance that Father James Carney’s remains would be found there.

Likewise, the family of David Baez were alerted the same closure might become available to them.

Given that the Honduran military and past government leaders had long known the corpses of the guerrillas executed in mid-September 1983 had been “disappeared” into the dense jungles of nearby Nicaragua, the raising of such hopes was and remains despicable.

No trace of Carney or Baez was discovered in the desolate graveyards. Only the remains of Contras who had died of wounds, injuries, or illness in the base field hospital.

Lilliam Cruz de Arguelio, David’s mother, received a formal letter dated August 2, 1984, from Robert L. Fretz, then the general counsel for the American embassy in Honduras. In it he expressed his “profound pain” upon learning of the death of her son, David, a “norteamericano.” Fretz urged Sra. Cruz de Arguelio to seek a formal death certificate from the Sandinista government. If she could obtain one, then he, at the embassy, would then issue a formal U.S. death certificate so her son’s affairs in the United States could be taken care of.

Jennifer Baez, David’s American wife, had told her husband that if he went to Nicaragua, she would leave him. She did. A formal death certificate from the U.S. embassy would help her resolve any lingering matters coming out of their marriage.

In Nicaragua, the EPS had continued to pay Baez’s wife his military wages, but one day those stopped. His brother, Eduardo, petitioned the EPS for a formal declaration of death so some form of income would continue for the widow and David’s children. His efforts were successful, and a certificate was issued, signed by Captain Marisol Castillo, stating, in part, that “Companero David Baez fell in battle” as a member of the Sandinista Popular Army.

The aftermath

Comandante Serapio Romero escaped capture and, in December 1983, re-crossed the Honduran-Nicaraguan border. Upon reporting to the EPS in Managua he wrote his after action report, the only other personal document known regarding the FAP and its demise. It is titled “Datos Sopre La Columna Del PRTC-H Que En Fi Ano 1983, Compatiera Por La Liberacion Del Pueblo Hondureno, En Las “Rofundidades Del Territorio – Junio 4 de 1984.”

Comandante “Gregorio” likewise escaped. He returned to Managua. “Gregorio” was an EPS intelligence officer from Masaya. It wasn’t until much later that he met with Eduardo Baez and identified himself as a survivor of the FAP. His real name was Darwin. Darwin, recalled Eduardo in one of his 2001 La Prensa interviews, spoke extremely well of his brother’s actions in Honduras.

General Gustavo Alvarez Martinez was forced from power in March 1984. He flew to Costa Rica where he made a brief speech to the media and later immigrated to the United States. He lived in Miami, Florida, and worked as a consultant for the Pentagon. In 1988, Alvarez returned to Honduras claiming a religious conversion. In 1989, he was shot to death outside his home by leftist guerrillas. He is best known for his comment to former U.S. Ambassador to Honduras Jack R. Binns: “Extralegal methods might be necessary to ‘take care’ of subversives.” He also praised the “Argentine method’ of dealing with the problem. Binns swiftly reported his concerns to the then-Reagan State Department. For his integrity he was replaced in 1982. John “The Black Prince” Negroponte became ambassador to Honduras.

Lieutenant Oscar Alvarez, GRAL Alvarez’s nephew, would climb the ranks in the Honduran Armed Forces. Upon retirement he became a dynamic politician and was named Honduras’ minister of security. As a private businessman he became wealthy. In December 2018, Honduran prosecutors implicated Alvarez in a significant corruption case. The year before he’d resigned from his government position and relocated to the United States (Texas) for “health reasons.”

It remains unknown which Honduran officer shot and killed Padre James Carney.

Lilliam Cruz de Arguelio passed away in 2008 without learning the whereabouts of her son’s remains.

Eduardo Baez Cruz left the Sandinista Party in 1986. He founded “Books for Children” in Nicaragua and became an outspoken critic of the failures of the revolution. He passed away in May 2010, his death attributed to a “fall.” He never stopped looking for his brother, David.

David Arturo Baez II, his grandmother Lilliam, and Eduardo Baez Cruz reflect on a picture of Comandante David Arturo Baez Cruz in 2001. (Credit: Juan O. Tamayo / SOFMAG)

Baez’s youngest son, just three months old when his father wrote him what would be the last communication between the two, changed his name to that of his father’s. Of his father’s doomed journey with the FAP, he has only offered “Honduras meant nothing to him.” He has never shared the contents of that last letter between father and son. Today he lives and works in Florida. Upon reading the original draft of this series in 2019 he wrote me to say how much he appreciated learning so much more than he did beforehand, and that the details of this story mirror what he’d been told by family members and friends over the years.

Well you may throw your rock and hide your hand

Workin’ in the dark against your fellow man

But as sure as God made black and white

What’s down in the dark will be brought to the light

… You can run on for a long time

Run on for a long time

Run on for a long time

Sooner or later God’ll cut you down

Sooner or later God’ll cut you down

“God’s gonna cut you down” – Johnny Cash

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DQTCS6aWRSc

******

This series is dedicated to the memories of Major General (ret) Eldon Bargewell and Colonel (ret) John McMullen. RIP, Warriors, RIP.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR — Greg Walker is an honorably retired “Green Beret”. He served with the 3/7th Special Forces Group (ABN) in Panama from 1982 until 1985. He is a Life member of the Special Operations Association and Special Forces Association. Today Greg lives and writes from his home in Sisters, Oregon, along with his service pup, Tommy.

Hi Mr. Walker,

My name is Francisco Zuniga. David Arturo was my uncle, youngest brother of my mother, Cecilia Zuniga Baez. I never knew my Uncle Arturo, as my parents called him when speaking of him. I spent my first birthday with him and his then wife in Panama in ’79.

It was good to read your story. It helps me know the uncle I never really met. It also helps me know more about my Mom’s side of the family. Everyone on the Baez side, including my mother, has already died, so I appreciate reading something that puts me in some sort of contact with them.

My second daughter is the spitting image of Tio (uncle) Arturo.

God bless you in your work, and thank you for defending our country.

Gratefully,

Francisco Zuniga

P.S. – I called my Uncle Arturo my mom’s youngest brother. I meant to say, ‘younger.’ My mom was second to Tio Adolfo, the oldest. Tio Eduardo was the baby.