11/13/1969 —

SSGT Ron Ray and

SFC Randy Suber MIA

SFC Randy Suber MIA

Decades Later an Chance Meeting Leads to Answers for Family

By John Stryker Meyer

Originally published in the November 2019 Sentinel

In late October 1969, I returned to CCN, to RT Idaho where Lynne M. Black Jr., was the team leader (One-Zero). He assumed command of the team when I left in April and I found an improved SOG recon team with South Vietnamese men I utterly respected. The team was tighter, more experienced since it lost six men in May 1968. The bitter irony of SOG at that time: The team had improved but the NVA had kicked up its efforts against SOG recon teams during the deadly, eight-year top secret war fought in Laos, Cambodia and North Vietnam under the aegis of the Military Assistance Command Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group, or simply SOG.

That message was hammered home on November 3, 1969, when the three Green Berets assigned to RT Maryland were wiped out by NVA troops, possibly NVA sappers — the highly trained NVA recon hunter killer teams. With RT Maryland, the indigenous troops survived the attack, escaped and evaded east to the South Vietnam border where, sadly, one team member was killed by friendly fire. In 1968, during our pre-mission intel briefings, we were warned about NVA sapper teams trained to hunt and kill Americans — a feat for which they received a medal from communist leaders in Hanoi. On January 1, 1969, that rumor turned into cold fact when a CCN recon team had all of the Americans killed, while the indigenous troops managed to escape from Laos.

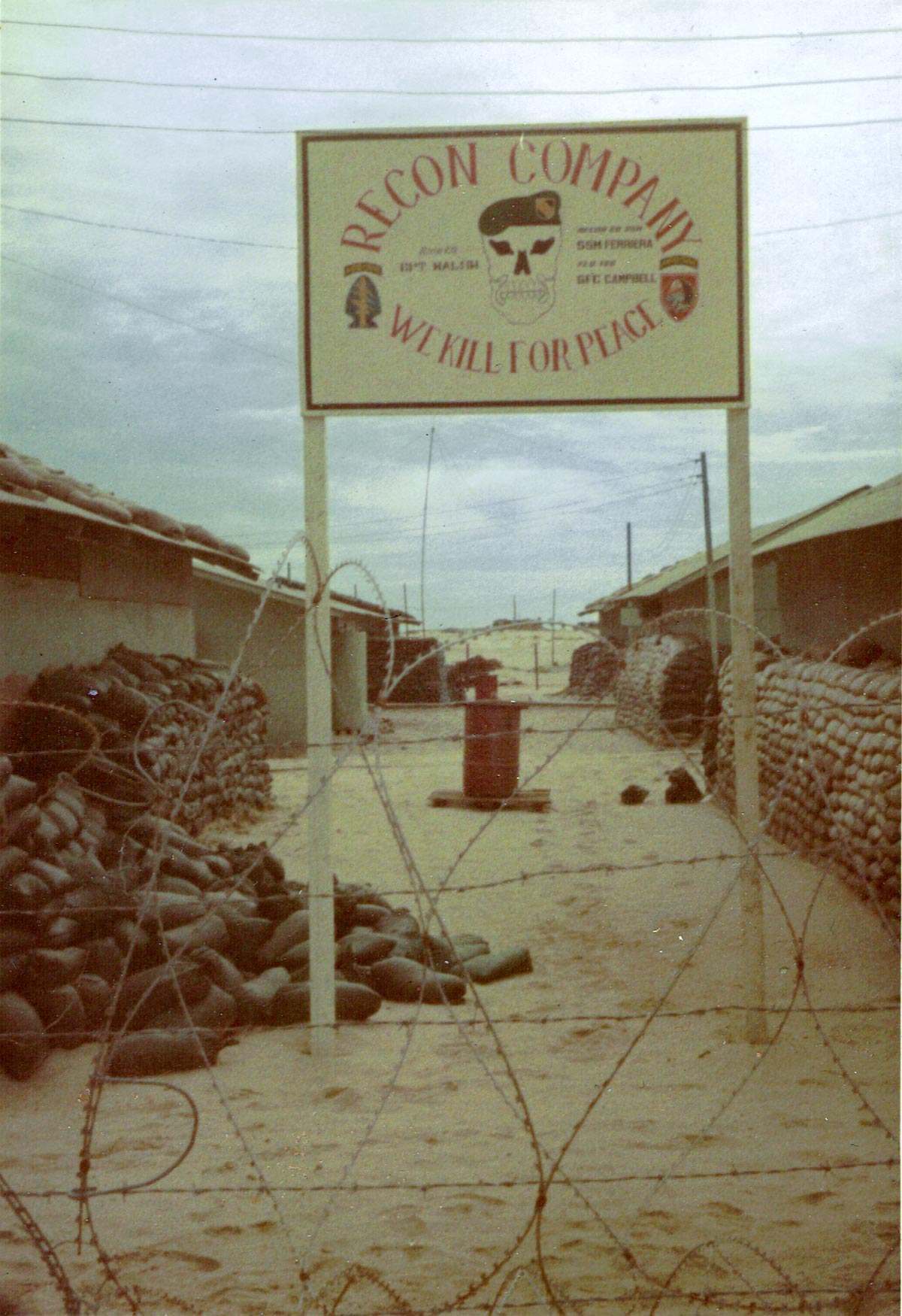

CCN Recon gate (Photo courtesy John S. Meyer)

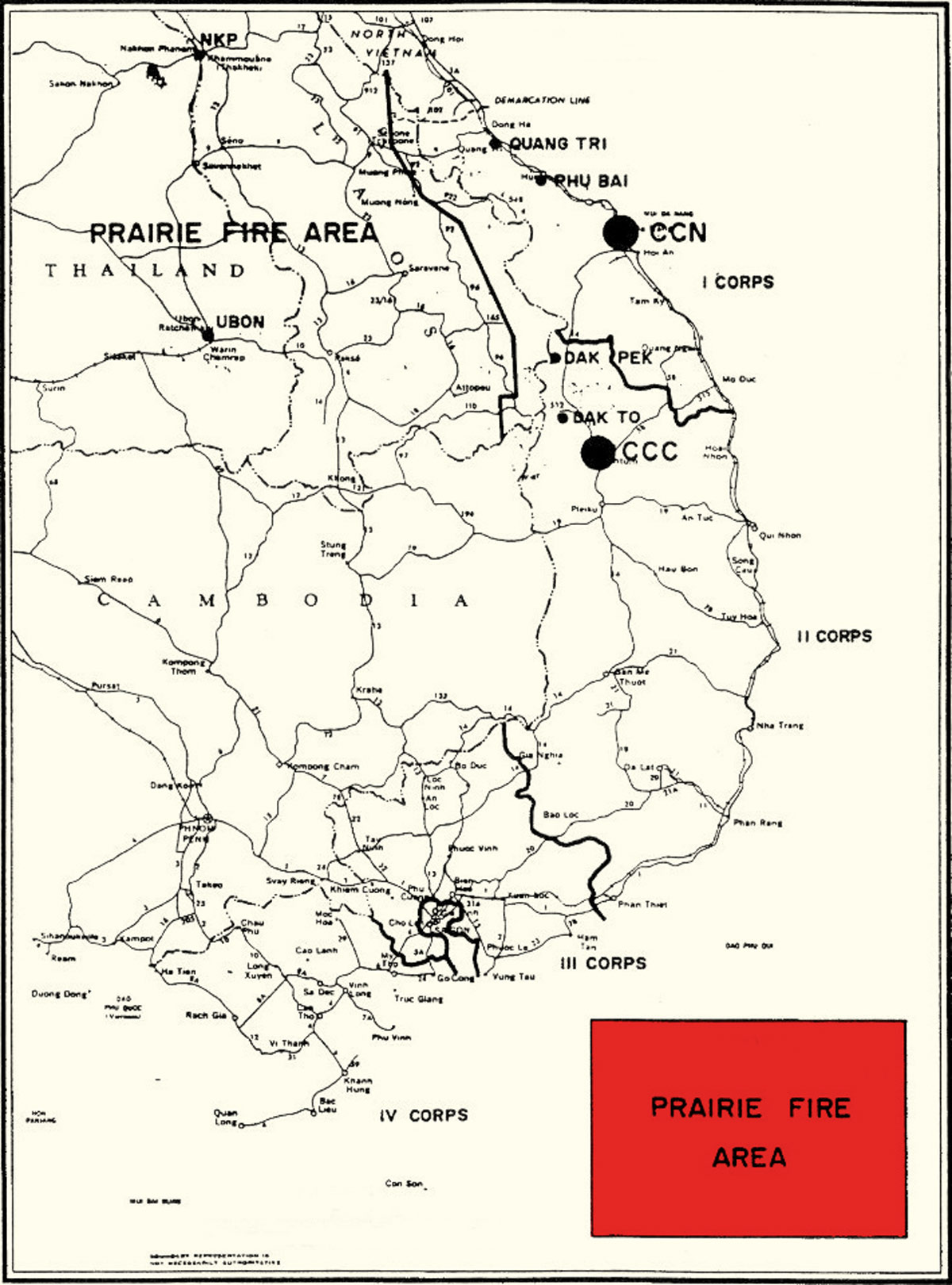

Mike Taylor and the Prairie Fire AO

Just how rough the Prairie Fire AO had become is attested to by Mike Taylor, who served five years in Vietnam with SF. His first experience with the PF AO, was in the air and on the ground with RT Oregon in September 1969. Mike was being transferred from MACV-SOG Ground Studies Group (OP-35), to the SOG Launch Site in Nakhon Phanom, Thailand. The launch site was under the operational control of OP-35 but it was administratively assigned to CCN. When Mike was in Da Nang in-processing to CCN, he flew his first Visual Reconnaissance (VR) flight with a Covey over Laos to scope out the CCN AO. His previous recon experience had been in Cambodia.

His reaction to the PF AO: “I was blown away by the size and scope of the Ho Chi Minh Trail, the number of NVA troops in the AO and the amount of Anti-Aircraft Artillery (AAA) that had been moved down from North Vietnam into the Prairie Fire AO. That night, at the CCN Club (not the Recon Club), I said to a friend, ‘I don’t know how you get people to run in that AO — it looked like New York City to me.’ I did not know the sorry excuse for a commander that CCN was cursed with at that time was standing behind me. He loudly proclaimed, ‘I am not having a coward at one of my launch sites.’ I replied, ‘It is not your launch site — it is OP-35’s launch site. I am not a coward and will go out with any team that will have me. Want to go with us?’ He said his duties wouldn’t permit that.”

Taylor then went down to the Recon Club where then-Sgt. Eldon Bargewell introduced him to Ron Ray, One-Zero of RT Oregon. “Ron said he never took ‘straphangers’, but if Randy Suber, the One-One on RT Oregon, would let me carry the radio I could go as the One-Two (radio operator). After a couple of days of Immediate Action (IA) drills all day and getting to know Ron and Randy through tennis, volleyball and beach time in the evenings, RT Oregon was inserted into Laos for a river watch of a ford on Route 23 over the Bang Xe Phai River. We were able to watch the ford for five days and reported quite a bit of NVA traffic on it, but Saigon never gave the OK to strike targets of opportunity. We were extracted without incident. It was a classic, successful recon mission.”

A week later, Taylor and RT Oregon were inserted into the A Shau Valley for an area recon. Midday on the second day, it became apparent they had trackers with dogs on the team’s trail and there were troop units maneuvering in the area. Ron Ray, quite rightly, got the team to a good, defensible LZ, declared a Tactical Emergency and requested an extraction. We took ground fire on the way out; everyone lived to run another day. Shortly after that mission, and taking the time to see, smell and feel the PF AO while on the ground with a respected CCN recon team, Taylor was shipped to his new duty station at NKP in Thailand.

During September and October Ron Ray and Randy Suber had also earned the respect of RT Idaho One-Zero Lynne M. Black Jr., who wrote to the Suber family in December 2018: “I knew Ray and Suber very well and had a lot of respect for all the men on RT Oregon.” He went on to say that RTs Oregon and Idaho “were the most active, ran more missions that any other team at CCN.” During September RT Oregon and RT Idaho had “trained up, become proficient, on the equipment” to conduct a joint radio direction finding (RDF) mission to interdict truck convoys along the Ho Chi Minh Trail….each of us flew visual recons selecting insertion and extraction points. We were ready to go when Oregon got assigned the 13 November mission.”

Map of Vietnam showing the Prairie Fire Area (as per Military Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group)

RT Oregon — November 13

On November 13, CCN was rocked with the bad news of RT Oregon having five of six men killed by NVA in Laos. “I’ll never forget that day as long as I live,” said Dan Thompson, an experienced SOG recon man who ran missions with RT Rhode Island and was flying as the Covey Rider for the insertion of RT Oregon. “It was one of those typical days in SOG, in the Prairie Fire AO,” Thompson said. “We were supposed to insert the team earlier in the day, but the insertion kept getting pushed back due to weather issues over the target area and getting asset coordination in place….we did a double insert. On the first LZ, the choppers went in on a dummy insertion, placing one of those “Nightingale” devices on the ground, which exploded in a sequential order making it sound like a firefight, with the chopper leaving the LZ, hoping to make it appear to the enemy the team left the LZ. We inserted RT Oregon on the second LZ, a long finger of mountain, high up about 15 miles inside Saravane Province in Laos. To be honest, I was a little nervous about the LZ because the vegetation was not jungle canopy, it was thin. But, the team went in, gave us a Team OK. We kept all assets nearby the target until we all got low on fuel and had to return to South Vietnam to refuel.

“Much to my absolute horror, no more than five minutes after the choppers and Covey headed east, we received the first radio beeper and call declaring a Prairie Fire Emergency, around 1600 hours. I was sick to my stomach,” Thompson said.

According to the top secret After Action Report, the six-man RT Oregon team was hit by NVA at approximately 1600 hours, attacking first from the west, with AK-47s blazing. Then NVA soldiers attacked from the northwest and southwest. During those initial fusillades of withering enemy gunfire, RT Oregon indigenous team member Vai was gunned down. During those adrenalin-pumping milliseconds, team members Nha and Thanh were killed when a claymore mine in one of their rucksacks exploded, killing them instantly.

Nguyen Van Bon, the only RT Oregon team member to survive the attack, later told debriefers, that as Ray returned fire he was felled by enemy gunfire while Suber was trying to make radio contact with any aircraft in the area. Efforts on his URC-10 ultra-high frequency emergency radio failed to make contact, Bon said. He observed Ray fall to the ground, groan and “become silent.” He shook the young staff sergeant, but Ray was unresponsive, his chest was covered with blood. Bon said he turned to Suber’s position when he noticed four enemy soldiers advancing toward the young sergeant. Suber picked up his weapon, pointed it toward the enemy only to experience weapon failure. He was instantly struck by enemy fire. Bon fired upon those enemy soldiers and called Suber’s name several times. Bon later told S-2 staff and polygraph experts that the brave Green Beret from Missouri neither moved nor answered his calls.

Bon then escaped from the deadly battle site by running down hill and into the darkened jungle to escape enemy soldiers. During the subsequent time, he heard sporadic shots fired and shouting to the north and west throughout the following day, according to the findings by the MIA Board of Proceedings conducted November 29, chaired by CCN Executive Officer Bill Angel, Capt. Robert Blatherwick Jr., and Capt. Michael D. O’Byrne. Also, during that time, Air Force personnel picked up at least five beepers alerts from an URC-10, which they assumed was a ploy by the NVA to draw in another team

SFC Randolph B. Suber

SSGT Ronald E. Ray

Bright Light

On November 14, RT Idaho was ready to conduct a Bright Light into the area where RT Oregon had fatal contact with the overwhelming numerically superior NVA force. A few days later, RT Idaho One-Zero Lynne M. Black Jr., later wrote, “The entire AO was still very hot … overrun with the enemy. Because of that we had to do a one-day in and out mission. If we had attempted to stay overnight on the ground we would have been lost as well. The insertion chopper landed us directly at the coordinates where we began a spiral outward search pattern. We found absolutely no trace of Oregon, not even shell casings indicating a battle….

“Randy Suber and Ron Ray were my friends. During the war, I didn’t make friends with other teams, let alone the guys on my team. Many times I watched teams depart for a mission never to return or come back all shot up. Each of us believed we were immortal … it would never happen to us. To this day I miss those guys. They were willing, even excited to go anywhere, anytime day or night….I know from personal experience it’s difficult to loose a brother to war.”

Taylor’s reaction: “Ron Ray and Randy Suber epitomized the Quiet Professionals we all aspired to be. They were damn good recon men. Their loss is a testament to the number and skill of the adversaries we faced in the Prairie Fire AO. By 1969, we had been doing the same thing, the same way for so long, it truly had become almost ‘Mission Impossible.’ The fact the guys continued the mission for three more years speaks volumes about the valor and courage of the SOG recon man.”

Family’s Pain and Uncertainty

With the demise of RT Oregon, the pain and suffering of Suber’s family began. It’s a bitter story that has unfolded hundreds of times during the secret war, where due to its top secret nature families could only be told minimal details about the loss of their Green Beret. Awards and decorations for valor in Laos were worded to say: “For valor in South Vietnam.”

A few days after November 13, 1969, the United States Army notified Suber’s mother at their home in Ballwin, Missouri that Randy Suber was listed as Missing-In-Action in Laos. They provided a brief written report (five or six sentences) indicating that the six-man reconnaissance team (RT Oregon led by “1-0” SSG Ron Ray and “1-1” SGT Randy Suber) was “attacked and overrun by a numerically superior enemy force” around 1600 hours about 15 miles inside Laos in Saravane Province. The report stated that three of the four indigenous team members were killed, and that both Ray and Suber were hit and unresponsive. The surviving team member, Nguyen Van Bon, was rescued several days later.

That was it for any official information to the Suber family for many years.

Given the Army’s apparent “mistrust” of reports from indigenous teammates, the family was skeptical about that sad, brief report. It was suggested more than once by the DoD that the surviving team member could have been a double-agent. In one of Randy’s early letters, he described his team as including indigenous men “… all are ex-NVA regulars. In fact, my Zero-One (Indigenous counterpart team leader) was a captain in the R20 Battalion in last year’s (1968) Tet Offensive … They are good soldiers … [but what] worries me … they quit one army once before …”

No one else was home with Mrs. Suber that fateful day. It must have been devastating for her, but she was incredibly tough. Ironically, she had just returned from the post office that day to mail seven pairs of Levi Strauss blue jeans to Randy for his indigenous teammates — per his special request in his last letter home dated October 26, 1969.

Jim, Randy’s younger brother, was 11 years old. Jim’s sister was three years older than Randy, who was 22. She was married to an Army captain and lived in Indianapolis. The oldest Suber brother, was away for his first year of college. Perhaps because of Jim’s age and the tremendous uncertainty, Suber’s parents waited to tell Jim of Randy’s status for many months. Jim, a sharp, curious boy knew something wasn’t right, but had little idea of the gravity of the situation, other than the extended absence of letters from Nam. Their hope, naturally, was that Randy would “turn up” before his scheduled tour ended, and they kept everything quiet from everyone in their community.

At SOAR XLV 2021, left to right, Jim Suber, Jr., Ch. 78 Gold Star member Jim Suber, SOG Recon veteran George Sternberg, and Ch. 78 member John Meyer. Jim Suber is the brother Randolph Suber. Jim Suber, brother of Randy Suber, MIA from Recon Team Oregon, spoke at the SOAR Memorial Breakfast on behalf of the family members. His speech was considered by many to be the highlight of the Breakfast. Listen to Jim’s speech at this link (at 11:06 minute mark).

When Dad eventually told Jim. He explained that MIA didn’t necessarily mean KIA. They held on for many years to the possibility that he was a POW — especially up until 1973. Of course, there was zero evidence, but they knew it was possible — especially for SF men — as manifested by Nick Rowe. Another sad memory, though, was some time before 1973, the DoD encouraged the Suber family (undoubtedly all MIA families) to send a special care package addressed to Randy at a specific prison in North Vietnam. “So, Mom sent a package — including woolen socks that she had knitted,” said Jim Suber. “The package was returned several months later with everything except those socks. Can you imagine the North Vietnamese soldier who opened the package, swiped the socks, and returned the package?!”

Strange as it must sound, the Suber family was extremely well-equipped for Randy’s situation. First, it was a military family. Their father was a lieutenant colonel in United States Air Force and was the commanding recruiter for Missouri and Illinois at the time Randy enlisted in the Army — a family irony. Mrs. Suber came from a long line of distinguished career military men – including an admiral who captained the largest ship sunk in World War I and an uncle who was second in command for the Pacific Campaign in World War II. He signed the formal Japanese document of surrender. She was beyond upset that Randy enlisted in the United States Army (October 26, 1967) and later volunteered for Vietnam. The biggest source of strength for the Suber family was its deep-rooted spiritual faith. Fifty years later, Jim Suber says their faith undoubtedly pulled their family through its tragic loss and years of bitter uncertainty and official silence.

According to Jim Suber, that bitter uncertainty was heightened when the family first learned many years later about “The Secret War.” “Naturally, we knew nothing about MACV-SOG,” Jim said. “Two big questions mystified us. What was Randy doing that was so cloaked in secrecy? Why hadn’t we ever heard from anyone that served with him? The answers to those questions drove me to learn as much as possible over the last, gee, fifty years.”

Suber’s parents dutifully attended almost every annual meeting for The National League of POW/MIA Families in Arlington, VA. They supported and deeply appreciated the government’s efforts, but, understandably, eventually became frustrated. Both passed on 16-plus years ago. “How surprised they would be to know that the DoD has conducted two extensive recovery operations at Site LA-00373; in October-December 2014 and March-April 2015 in efforts to locate the remains of Suber and Ray.

First Meaningful Breakthrough

“The first meaningful breakthrough came once there were some books written by SOG men, published twenty plus years later. Their descriptions of SOG’s operation and missions helped immensely. One of those first books came from MACV-SOG soldier, the late Harve Saal, who was assigned to FOB 1, 3 and 4 in 1967-68. I connected with him through The Drop in 1989 just as he was completing a four-volume, 1,000 page history of MACV-SOG (SOG – MACV Studies and Observations Group – Behind Enemy Lines published in 1990). It was not easy to read, but his information, at least, opened our eyes and definitely explained why no fellow SOG men had contacted us. Harve answered those two questions, and showed tremendous compassion to the Suber family along the way. That really helped all of us — especially my parents. Sadly, Harve passed on from lung cancer a few years later.

“Numerous books started appearing about MACV-SOG, and I read as many as I could find. Many of them were extremely well-written, and all of them helped in some way. My favorites included To Bear Any Burden by Al Santoli (1985), SOG: The Secret Wars of America’s Commandos in Vietnam by John Plaster (1997), and SOG: A Photo History of the Secret Wars—also by John Plaster (2000), John Stryker Meyer’s Across the Fence (2011), Lynne M. Black Jr.’s Whisky Tango Foxtrot (2011), Meyer’s SOG Chronicles – Volume I (2018), The Dying Place by David Maurer, and We Few by Nick Brokhausen (2018).

“While none of those books provided specific stories about Ron Ray or Randy Suber (other than the after-action report), they gave bigger context to Randy’s comments in a letter dated September 1, 1969. ‘CCN took a beating last week. Six people were killed in action and ten were seriously wounded … it’s bad here as 26 have died in last three months … My closest friend was killed two days ago … I was in a different target area at the time, but listened to it on the radio.’ He also added, ‘On my last target I was put in for the Bronze with Valor. I guess that is supposed to make me forget and drive on.’ That had to be on his first mission. In a letter a few days later, he added, ‘I can’t tell you much about the mission … one thing for sure: I am in an extremely hot and dangerous assignment.’ ”

Randy Suber

A Chance Meeting — A Major Breakthrough

The major breakthrough for Jim Suber came 49 years later in January 2018. “I unexpectedly met John Stryker Meyer (“Tilt”) at the DPAA family update meeting in San Diego. He certainly knew Ron Ray and Randy Suber, and promised to introduce me to more who knew them even better. That, indeed, is exactly what he did. Soon, John connected me to, first, Mike Taylor, who ran on two missions with Ron and Randy (a trail watch along the Xe Bang Phai River); second, Dan Thompson, the covey rider for the LZ insertion on the November 13th mission; and, third, Lynne Black, the team leader for RT Idaho that was prepped to Bright Light and returned to the last known coordinates for RT Oregon a few days later. Each of these men have provided first-hand accounts of RT Oregon and that fateful day on November 13, 1969. Honestly, how do you get much closer than that on a case that is now 50 years old??? What an absolute blessing!

“It’s been an honor to meet all the men of MACV-SOG over the last two years. Connecting with them has, beyond a doubt, answered those two questions — and revealed the incredible valor and patriotism of the men of SOG! My parents would be so pleased to know of these connections and of the incredible heroism demonstrated by MACV-SOG. My wife and children have been incredibly supportive of me — especially our son, James Randolph Suber, who has discovered even more information about the men of SOG and the incredible valor of every SOG recon man through his extraordinary research skills. Throughout the journey, Randy’s example has set a standard that almost always feels way too high, but has absolutely made me a better person along the way.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR — John Stryker Meyer entered the Army Dec. 1, 1966. He completed basic training at Ft. Dix, New Jersey, advanced infantry training at Ft. Gordon, Georgia, jump school at Ft. Benning, Georgia, and graduated from the Special Forces Qualification Course in Dec. 1967.

He arrived at FOB 1 Phu Bai in May 1968, where he joined Spike Team Idaho, which transferred to Command & Control North, CCN in Da Nang, January 1969. He remained on ST Idaho to the end of his tour of duty in late April, returned to the U.S. and was assigned to E Company in the 10th Special Forces Group at Ft. Devens, Massachusetts, until October 1969, when he rejoined RT Idaho at CCN. That tour of duty ended suddenly in April 1970.

He returned to the states, completed his college education at Trenton State College, where he was editor of The Signal school newspaper for two years. In 2021 Meyer and his wife of 26 years, Anna, moved to Tennessee, where he is working on his fourth book on the secret war, continuing to do SOG podcasts working with battle-hardened combat veteran Navy SEAL and master podcaster Jocko Willink.

Visit John’s excellent website sogchronicles.com. His website contains information about all of his books. You can also find all of his SOGCast podcasts and other podcast interviews. In addition, the website includes in stories of MACV-SOG Medal of Honor recipients, MIAs and a collection of videos.

Leave A Comment