Wounded Warrior

Part One

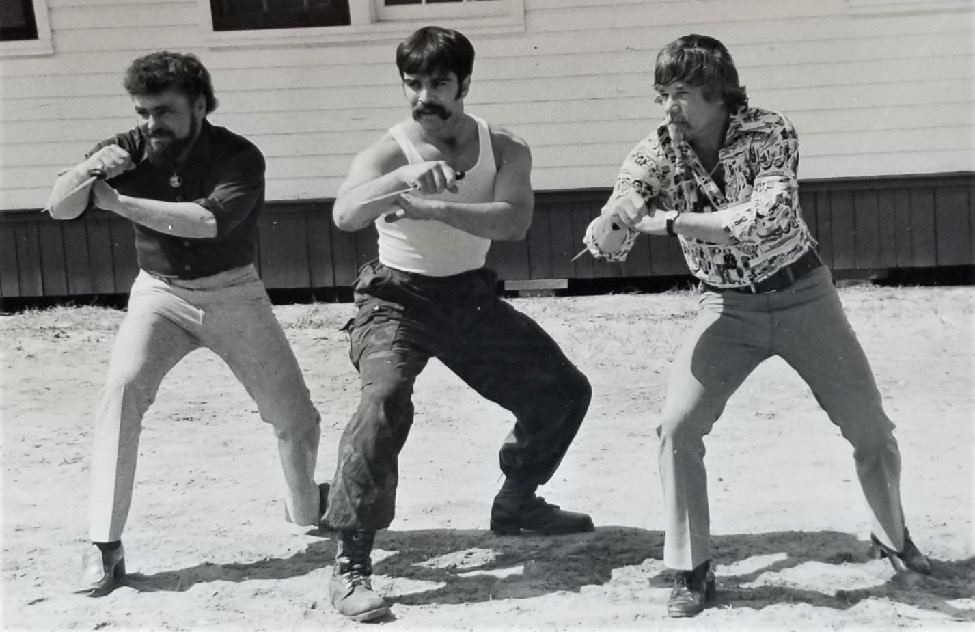

Hand to Hand Combat Instructor Michael D. Echanis with 1st Generation DELTA operators (Author Collection)

By Greg Walker (ret),

USA Special Forces

Early Days

Michael Dick Echanis was born on November 16, 1950, in Nampa, Idaho. Mike, with two younger brothers and a sister, was the oldest of the four Echanis children. He grew up in eastern Oregon in the small rural town of Ontario where as a young man he became an avid outdoorsman and martial artist. Attending Ontario High School Mike was a solid academic student who participated in track and field as well as basketball, a sport he was particularly fond of and demonstrated exceptional skill as an “Ontario Tiger”.

Echanis’ first close quarters combat instructor was WW2 paratrooper Charles “Chick” Keim. Keim served with 501st Parachute Infantry, 101st Airborne Division, jumping into Normandy at the onset of the Allied invasion of Europe, then again during Operation Market Garden. At the end of the war Chick settled in Ontario, Oregon, where he would soon marry into the Echanis family. “Mike was about 14 when we met,” he told me during our first interview together. He wanted to learn all the “dirty tricks” we’d been taught as paratroopers when it came to hand to hand combat. We became fast friends and I later taught him how to SCUBA dive, as well.”

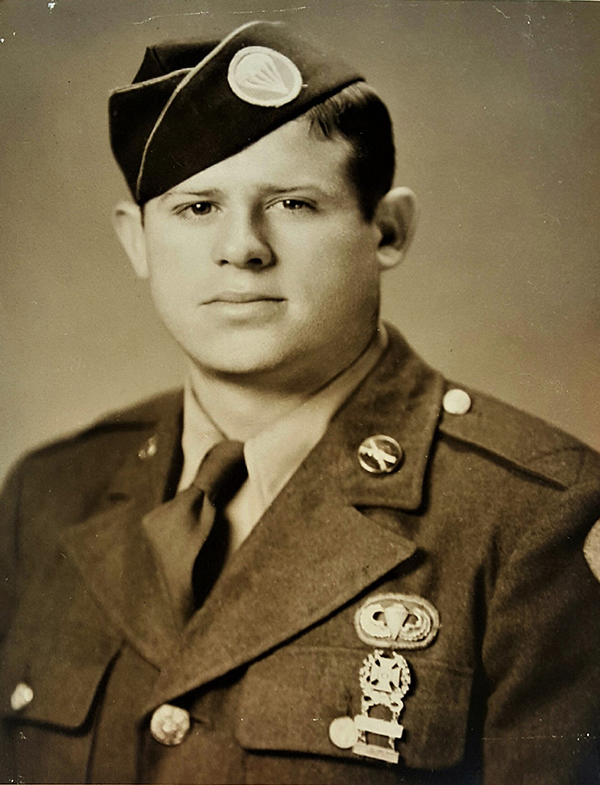

Charles “Chick” Keim (September 12, 1922 – June 29, 2016) fought with the 501st “Screaming Eagles” during WW2. His awards and decorations include the Bronze Star for Valor. “My favorite weapon was the .45 caliber Tommy Gun”, he recalled. (Author Collection)

Becoming a Soldier

Military service runs strong in the Echanis Family and while Mike was in high school his cousin, Major Joseph Ygnacio Echanis, was shot down over Laos and designated as Missing in Action (http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=24338117).

According to his family young Mike, who early on showed a great interest in serving his country in the military, felt that if he could get to Vietnam under the right circumstances he might be able to learn what had happened to his cousin. Echanis skipped his high school graduation ceremony and joined the Army on May 12, 1969.

Mike attended Basic Training at Fort Ord, California, and then Advance Infantry Training at Fort Gordon, Georgia. While there he volunteered for Special Forces training and was accepted. Upon his successful graduation from AIT he went on to Fort Benning, Georgia, where he attended Airborne training in October 1969 where he was awarded the “Silver Wings” of a paratrooper.

Echanis, arriving at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, began the Special Forces Qualification Course, Class 70-18. Upon completing Phase II of the demanding course he and several other candidates were informed they would not be going to Vietnam upon graduation but rather to Okinawa where they’d be assigned to the 1st Special Forces Group (ABN). Mike’s response was near immediate. He, along with another candidate, terminated SFQC, requesting to be sent to Vietnam immediately. His request was granted with the caveat given his class standing that he could return and complete the “Q” course at a later date.

After terminating from the SFQC, Echanis took 30 days leave at home before leaving for Vietnam where he was accepted and assigned to Charlie Rangers. (Author Collection)

Rangers Lead the Way

Arriving in Vietnam on March 23, 1970 and upon being assigned to the 173rd ABN, Specialist 4th Class Michael Echanis volunteered for duty with the 75th Ranger Infantry as a scout-observer. He was accepted and assigned to Charlie Company (Ranger), 75th Infantry. Known as “Charlie Rangers” the company operated under control of I Field Force (Vietnam) and was based at Ahn Khe. The company was moved to Pleiku on March 29, 1970, where it came under operational control of the aerial 7th Squadron of the 7th Cavalry. The Rangers conducted thirty-two patrols in the far western border areas of the Central Highlands in only a few very short weeks.

On April 19th the company was attached to the 3rd Battalion, 506th Infantry and relocated to Ahn Khe, where it was targeted against the 95th NVA Regiment in the Mang Yang Pass area of Binh Dinh Province

On May 4, 1970, the company was placed under the operational control of the 4th Infantry Division. On May 5th, Operation BINH TAY I was launched with the invasion of Cambodia’s Ratanaktri Province. Ranger combat actions during the operation were fierce and sometimes adverse to include the Rangers themselves being ambushed. Company C concluded Operation Binh Tay I with thirty patrol observations of enemy personnel, five NVA killed, and fifteen weapons captured. On May 24, 1970, Company C was pulled out of Cambodia and released from 4th Infantry Division control.

Echanis completed the “Welcome to Charlie Rangers” course after signing in and prepared to be assigned to a Ranger recon team. He was elated.

Becoming a Wounded Warrior

It was May 6, 1970, and SP4 Echanis had been in Vietnam for a month. Traveling with three other Rangers in a military truck through the Ahn Khe Pass the vehicle was ambushed by an estimated company size element of North Vietnamese regulars. Within minutes both the driver and assistant driver of the truck were badly wounded as well as the rangers themselves.

Echanis, having opened fire on the enemy with his rifle as the vehicle came under attack, jumped from the truck as it left the road and skidded into a ditch turning onto its left side. Struck in his left foot by AK47 fire Mike continued to engage the NVA. Bullet fragmentation then struck him between the eyes after careening off the bridge of his sunglasses. With blood now pouring down into his eyes the young ranger continued to fire on the advancing enemy troops. Another AK round hit him in his right foot, traveling up into and lodging in his calf. Still firing Echanis was struck a fourth time by enemy fire across one forearm. His mother, Pat Echanis, would later recall her son describing the scene as U.S. helicopters arrived to relieve the embattled Rangers. “Mike told me even as the helicopter was arriving the enemy was so close to him he could have reached out and touched them.”

In 2017, I interviewed Ed Toliver, who was the company executive officer at the time of the An Khe ambush. “My recollection after 50 years is that the driver was wounded in the hand and drove the truck into the bank on the up-hill side of the curve. He was having trouble controlling the vehicle and didn’t want to go over the edge. Echanis took a round in the bottom of the foot as the truck came around the hairpin curve. He then returned fire over the tail gate and was struck a glancing blow in the forehead by spalling when a round hit the tail gate. The blood flowing into his eyes prevented him from seeing clearly. I believe an MP light armored vehicle showed up about that time and relieved the ambush.”

“I recall is that he had to go to Charang Valley (173d ABN Rear Echelon) to take care of some admin matter. Whether he was still in school or was sent back from the teams, I don’t recall. I was the Company XO. I really knew nothing about him until the ambush in the An Khe Pass when I wrote his BSM citation.

“I next saw him in Jake Jakovenko’s team room in ’75 but I didn’t link him to Charlie Rangers. It wasn’t until about ’86 when I was killing time in the Pentagon and saw a book about him in the bookstore and started browsing that I realized who he was. I recognized the BSM citation in the book from the one I wrote.”

The ambush of the rangers was the highest casualty producing such combat action for Charlie Rangers at that time. Echanis, ultimately the only ranger capable of returning fire, was able to hold the NVA off until a nearby element from the South Korean White Horse Division arrived along with U.S. reinforcements brought in by helo. Battered, bloody, and in a state of adrenalin fueled shock the young ranger was coaxed by another ranger to surrender his now empty rifle.

Years later Mike recounted the ambush to a close friend while teaching Hwa Rang Do in Los Angeles.

“Mike told me about the ambush,” recalls Teresa Carr, who was both a student and an office helper at the HWD dojang Mike was instructing at. “We were sitting outside during a break. He told me when the Americans arrived an officer tried to take his rifle from him. He refused to let it go. He said he had it clutched in his right hand and in his left fist he was clutching the Saint Christopher medal he always wore. Mike said he remembered he was crying and shaking. He was scared to death. Finally, he released the rifle, but he remembered telling the officer he wouldn’t give him his Saint Christopher amulet.”

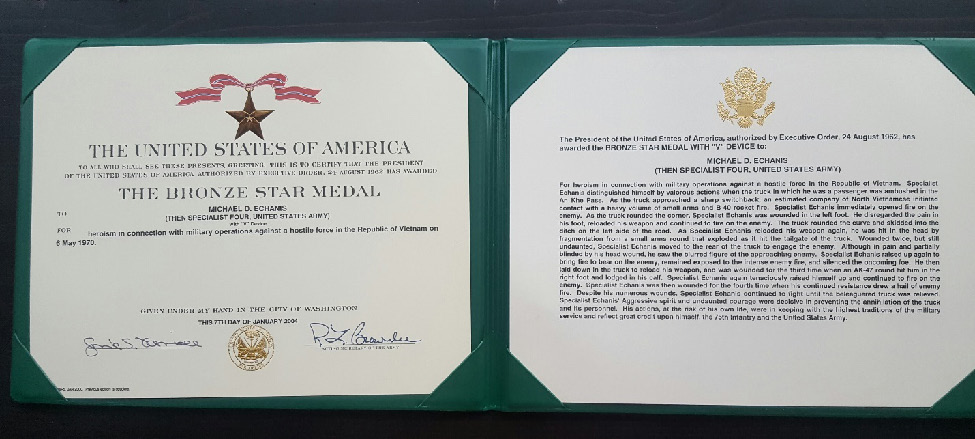

For his heroic actions during the ambush Mike Echanis was awarded the Bronze Star with “V” device on July 15, 1970. His citation reads in part “Despite his numerous wounds, Specialist Echanis continued to fight until the beleaguered truck was relieved. Specialist Echanis’ aggressive spirit and undaunted courage were decisive in preventing the annihilation of the truck and its personnel.”

Recovery and Rehabilitation

Upon aerial medevac Specialist Echanis was sent to the Army 17th Field Hospital and then to the 249th General Hospital in Japan. There his surgeon, reflecting on how young the soldier was, elected not to amputate Mike’s seriously injured right lower leg. Years later Pat Echanis recalls the correspondence with the doctor who offered he wanted to give her son a fighting chance so “he patched him up as best he could and sent him to Letterman Army Hospital”. At Letterman in San Francisco, California, Specialist Echanis would undergo 7 months of grueling surgeries and a complicated casting process that left him exhausted. He went from 150 to 123 pounds during this period.

The weight loss and being bedridden left him emaciated and depressed. The bullet wound to his head resulted in a diagnosis of cephalalgia, or chronic headaches affecting the frontal and temporal areas of his brain. Although his wound to his left foot healed the right foot and calf were badly and permanently damaged. Echanis suffered foot drop with contracture of the third, fourth and fifth toes due to nerve and artery interruption. In addition, he now had vasomotor instability of his right lower leg. He was medically considered crippled.

His cousin, Michael L. Echanis, remembers “Little Mike” describing to him his lack of overall feeling in his right lower leg after his return from Vietnam. “His nerve endings were badly injured by his wounds,” offers “Big Mike” Echanis. “His entire lower right leg was constantly numb, and he lived in chronic pain.”

On December 18, 1970, Mike Echanis was medically retired from military service. The VA in Boise, Idaho, would rate him as being 100% disabled and provide him with a small pension. He returned home with a soft brace for his crippled right lower leg, an orthopedic insert in his right shoe, a cane and an uncertain future as a wounded warrior in the early 1970s. “Mike was never a quitter,” remembers his mother. “He was stubborn even as a little boy. He always told you exactly what he thought. He questioned everything. He was tough.”

Adopted by Frank Echanis, Pat Echanis’ second husband, Mike and his mother were exceptionally close. Today mother and son are buried side by side in Ontario, Oregon. (Author Collection)

For two months the young veteran lived in a basement room in the family home which he seldom left. His friends and family would visit him there and his father, Frank, had a pool table put in the room so Mike could entertain himself and his friends. “He was a great pool player,” offers Frank. “He learned how to play pool here in Ontario before the Army and he could make all the trick shots.” When exactly Mike decided he would learn to walk again is unclear but when he did he asked his mother to get him a pair of soft desert boots, the only footwear he could wear comfortably, and he began teaching himself, step by step. “He used the pool table in his room to support himself,” the family recalls. “He’d brace himself on it and walk around and around it.”

The soft brace meant to reduce the ill-effects of his foot drop condition was tossed aside. Echanis strengthened his upper thigh and hip muscles and in doing so developed a technique where he would flex and tighten his upper right leg as he took a step, literally but discreetly throwing his lower leg and foot forward. In his soft shoes and with great will power he not only appeared to be walking normally but in time he was able to run again without support. Randy Wanner, who became Mike’s HwaRang Do instructor and a close confidant, described Echanis as having “acquired a bouncing, rolling step” with which he moved swiftly. Even so, without wearing his soft shoes Mike experienced extreme difficulty movement and balance wise to include not being unable to hold himself up when bathing.

Two hometown physicians and friends of the family, Dr. Baker and Dr. Sanders, encouraged Mike to take up weightlifting to increase his potential for recovery. The recommended rehabilitation program included a diet heavy with nutritional supplements and a high intake of protein, most often through homemade milkshakes. Mike enhanced his physical training program by incorporating the anabolic steroid Dianabol, popular in the 1970s among European and American body builders. He went from 123 pounds post hospital care to a healthy two hundred pounds, diligently exercising every day and pushing himself from one physical and mental goal to the next without compromise.

Interested in the martial arts as a young boy he took Judo up again and then Karate in Boise, Idaho. He later trained as a boxer with Al Barras, a Boise based trainer, and would go on to fight as a heavy weight locally. By the time Echanis was awarded his 1st DAN black belt in the Korean martial art HwaRang Do his “high altitude” kicking abilities were extraordinary. “Mike was very proud of his spinning kicks,” remembers retired SEAL Skip Crane, a good friend of the martial artist. “He loved demonstrating how powerful and how high he could effectively kick you.”

In 1975 Mike moved to southern California where he attained his 1st DAN black belt in HwaRang Do. Still, the love of military life and his desire to serve his country in a meaningful manner continued to pull deeply at him. If he could not soldier any longer could he use his remarkable self discoveries about the strength of the human mind and will to overcome fear, pain and physical disability to train soldiers, specifically Special Operations soldiers like the Rangers, Green Berets and Navy SEALs?

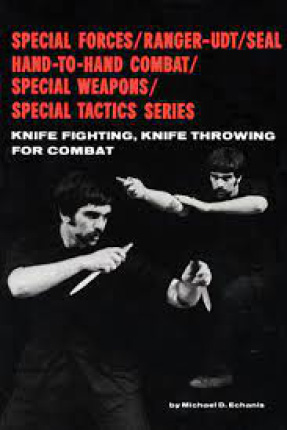

In 1976, in a letter to his family from Fort Bragg, North Carolina, after being appointed as the Senior Hand to Hand and Special Weapons Instructor to the United States Army’s John F. Kennedy Center for Military Assistance, Mike wrote “I am completing a 6-week [military hand to hand training] film and completing an Army Manual [on the same subject]. I am standardizing the Army’s Hand to Hand system. It’s a lot of work, 5:00 in the morning til 2300 every nite…I feel I have found my profession and I know the military is my home.”

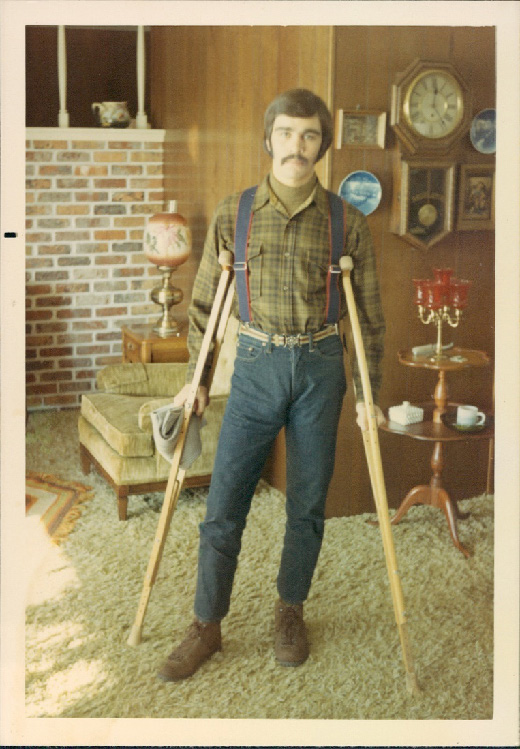

Medically discharged with a 100% Veteran disability rating Mike Echanis fell into a deep, dark depression. Encouraged by his family and childhood friend, Chuck Sanders, Mike determined he would regain his mobility relying, in part, on his martial arts training (Author Collection)

The initial results of his work at Fort Bragg would be presented in the January-February 1976 issue of VERITAS, the official publication of the elite Foreign Area Officer (FAO) program in an article simply entitled “HwaRang Do”.

In February 1977, in a formal letter from the 5th Special Forces Group (ABN) at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, then Major Juan A. Montez said the following of Echanis’ training programs – “Mr. Echanis’ totally comprehensive approach to the development of soldiers, physically, mentally, and his focus upon the fighting spirit of men, gives us an approach to hand to hand combat well exceeding the usual physical programs developed today.

“His programs dwell on the precise needs of the individual soldier, with his primary focus upon the Physical-Psychological development of the man concerned. Instilling confidence through training, these men acquire the proper state of mind for battle and the physical ability to react decisively to a vast and varied amount of hand-to-hand combat situations. The reaction to these programs of instruction by the individual soldier have been excellent.”

Montez would also point out the U.S. military had not developed a new [hand to hand combatives program] since the O’Neal System was enacted in 1945. “Mr. Echanis’ training programs exceed any close-quarters combatives manuals, books or training programs that I have viewed up to this time,” he wrote.

In the August 2022 Sentinel:

Wounded Warrior Part 2

Following recovery and rehabilitation, Greg Walker discusses Echanis’ phenomenal transition from being a medically retired/crippled Vietnam veteran to becoming the senior hand to hand and special weapons instructor for the Army’s elite Green Berets and Navy SEALs. Following this period is Echanis’ involvement in Nicaragua, leading to the end of his journey.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Greg Walker is an honorably retired “Green Beret” and lifelong martial artist whose close friendship with Ms. Pat Echanis, Michael Echanis’ mother, has resulted in an upcoming book about this Army ranger and Special Forces legend.

Today, Greg lives and writes from his home in Sisters, Oregon.

Greg Walker and his service pup, Tommy

Greg, Enjoyed your article about Mike Echanis. I knew him a little at FBNC 1976-77. Met him through Chuck Sanders, another truly great warrior, Rest in peace, DOL

Bob McKague

Great Read. I was one of his students in 1976-77 and served in the same company as Chuck Sanders. Looking forward to Part 2.

Michael Echanis was a legendary warrior when I served in the 2/75 Ranger Battalion. Now learning Mike’s full story and what he overcame is incredible. Thanks Greg!!! I’m diving into P2. RLTW

Greg,

Great great read, I went through high school with Mike in Ontario, Oregon. I spend my time in Vietnam with G Company (Rangers) 23th Infantry Division. After that I spent 11 years with Special Forces. I will look up your book and order it. Thank you for your work.