The Escape of Anh Tuan Tran: Part Two

Anh Tuan’s living quarters in the UNHCR camp in Malaysia. (Photo courtesy Anh Tuan Tran)

Editors Note — In the Part One of Anh Tuan Tran’s story, which appeared in the September issue of the Sentinel, Anh Tuan Tran revealed how, after joining the South Vietnamese Marines as a lieutenant in 1972 he became part of a prestigious unit that would often be the first line of defense against the communist North Vietnamese Army. In early 1975, as the North increased its activities, resulting in the overthrow of the South Vietnamese Government, Anh Tuan Tran was wounded in action and ended up turning himself in, as instructed by the new Government, for a “ten day” re-education camp. That, as was typical of the communists, was a lie. After much torture and inhumane conditions and multiple escapes, his life improved dramatically when he was transferred to the Suoi Mau re-education labor camp in Bien How Province.

By Marc Phillip Yablonka

Author and Military Journalist

In the camp, prisoners were organized into what Tuan called “láng”, a new VC word that meant a group of 15 to 20 people living together in a kind of barracks made of concrete floors, steel rooftops, and walls with no doors.

“There were openings on both ends of the batiment [building] for entering and exiting. We made our beds next to each other on both sides along the wall, sparing the center alley to access the two entrances. After the first night on a bare cement floor, I woke up with cramps in my hands and legs. I couldn’t move for a few minutes, a sign of rheumatism from the humidity and the vapor emerging from the floor during nighttime.”

Later, while he was working on various cleaning projects around the camp, Tuan found material to make a kind of personal tarp cover to isolate himself from the cement floor. From the sand bags around an old, abandoned observation fortification post, he ripped and collected pieces of dark green nylon covers, sewing them together to make the underlying of his bed.

“You cannot believe the creativity and the patience you put into making a needle out of a small piece of copper wire. You need something sharp and thin to make the hole. You scratch it little by little, and make many attempts to succeed. It was soft, but it did the job,” he said.

This was during a time when Tuan worked inside the camp perimeter. He was able to scavenge stuff left over and make something out of it.

“I remember making a comb for my beautiful sister Cam Tu out of a piece of aluminum I found buried in the soil. There was one time we had to carry bags of rice from a truck into storage. Some of us punched holes into the bags and stole pockets of rice. Because of jealousy, one guy was denounced and sent to “chuong cop” (a tiger cage with no cover, out in the hot sun) until the afternoon of the next day.”

Life was a little better there than Chi Hoà prison. He had more freedom to move about after work. The prisoners had access to a well for showers. Later on, they cultivated the ingredients rau muong [amaranth], and rau den [spinach], to make soup. They made wooden sandals and clothes out of any kind of materials they could salvage from in work sites.

“But our portion of rice remained small. We were always hungry,” Tuan added.

For some reason, the VC preferred to move prisoners at night.

“One evening, we were suddenly told to get ready with our belongings. Prisoners with good behavior were lucky to have contact with family and were allowed to receive parcels of food, medicine, and clothes.”

Then Tuan and his fellow prisoners were organized into groups and led down to the courtyard.

“It was a real military operation,” he said. “The surroundings were bright with lights. AKs were everywhere. Group by group we were loaded onto Molotov trucks. The convoy headed to a camp that later we knew as Suoi Mau re-education camp. The camp used to hold VC prisoners (“trat giam tu binh Cong San”), manned by ARVN military police. Now it was the other way around, NVA troops stayed outside the perimeter, monitoring movement from watch towers, and entering the camp every morning with armed escorts to run activities inside the camp.”

“Among us, we were always aware of `an ten’ (Vietnamese for antenna). Weak people, or smart ones who wanted to stay alive longer, reported to the “can bo quan giao” (educational cadre). There were “can bo quan giao” usually with a pistol at their sides, and “bo doi quan che” (guarding troops) with their AKs ready to shoot if any gestures were perceived as rebellion.”

Because they were inmates, prisoners had to toil very hard and study hard to become what the VC termed a “citizen.” To become a citizen, they had to prove that they were good in their re-education duties.

“They never defined the word ‘good.’ For some, ‘good’ meant to spy and report on your fellow inmates. That’s why we always had an ten, he said.

“Even among the high-ranking officers (captains, colonels and generals) sent to the north, after a few years, “an ten” existed. Survival instinct, I guess.”

The only positive thing to happen to Tuan in that re-education camp was that he was allowed to receive a visit from his mother. This happened just as he was planning a second escape by land to Thailand.

“Suddenly, I was released,” Tuan said. He went back to Saigon to live with his aunt and work in her sugar distillery for a year.

Tuan seems to slip into a stream of conscious dream at this point, worried that he might have forgotten even a portion of his tribulations.

“I think I’m in trouble. There are holes in my memory. There are things I know happened that I can’t place in any phases of my life. I was really sick one time. Almost gone and somehow came back. There was that doctor who nursed me back to life. I can still see his face with his white-rimmed glasses, but I can’t remember his name, when or where it happened.

“And there was one time I was infected by that skin disease. I got parasites that crawled under my skin all over my body, but not my face. It was very itchy. I couldn’t help but scratch and every time I did, it got infected. I scratched, and I scratched, and blood and pus came out. It hurt, and I felt dirty. It was all over my hands. I couldn’t hold anything. Every time I contracted my fingers, they burst open, spilling pus and blood. The only medicine I had was salt water. I poured and rubbed it into my wounds and, oh my God. It hurt. I lived with it, I don’t remember how long, but a very long time.

“There is that image that will haunt me forever. I walked into that first-aid room with a row of bamboo beds on each side full of people. Everyone had dysentery; there was one guy laying there with no pants. His hemorrhoid rectum was like a big flower. Flies were all over it, making a buzzing noise.”

Tuan and his fellow prisoners’ terror increased with the arrival in the re-education camp of what he called the “Bo Vang” [Literally “Yellow Cows’, the police arm of the VC].

“We used to see the olive uniform of the NVA guarding us. The green color [uniforms] blended nicely with the environment. Then we became alarmed with the pronounced yellow uniform of the “Cong An” [VC] forces around us.”

In the old days, Tuan used to call police Canh Sat; Cong An was reserved for the secret police and it usually conjured up images of fear because the term was associated with torture.

“When we saw Cong An replacing usual NVA forces, we wondered what was going to happen. Were torture chambers the next phase?”

What Tuan referred to as “Bo Doi [infantry troops] were usually needed for combat situations, while Cong An specialized in the control of civilians.

“Bo Doi were more into external body movements. They made sure there were no revolts, no escapes, no fighting, no resistance, on the part of prisoners. While Cong An were more into the mind game of the prisoners. I don’t know who invented the nickname “Bo Vang, but it’s meaning pointed to the color frappant [striking color] of their uniforms. And the cow, which is an animal, representing stupidity and obedience,” Tuan said.

“But the name calling didn’t reflect the reality. The Bo Vang were not stupid. They were more adept at controlling the thinking and the daily activities of the prisoners. The ‘Can Bo Quan Giao’ [administrators] knew more about each prisoner than the previous one. And with the yellow bovines, we started working outside the perimeter of the camp. We started doing hard labor jobs by clearing the forest to plant “khoai mi” [cassava]. We competed against each other for more production, there was a quota to be accomplished each day.”

The administrators used different tactics to improve productivity, according to Tuan. One used encouragement. He sent two prisoners to collect cassava, cook and distribute it to prisoners of his lang [barracks] during break time. The other punished the prisoners by cutting down their portion and making them work longer hours.

“Your life became more tolerable or more difficult, depending on each individual yellow cow’s style of supervision. One prisoner in my lang became a target of one newly appointed young cow. His physical appearance — he wore glasses and his large bald forehead announced an intellectual mind — déclenche [set off] a cruel response from the cow,” Tuan recalled.

“Maybe all of the cows suffered an ‘complexe d’infériorité’ [inferiority complex] towards people of the south. In the field, he ordered the entire lang to stop working and gather around for a lesson on how to be more productive. He singled out the old guy with the glasses and lectured him about productivity. He punished his laziness by hitting him many times with a ‘cai don ganh’, a bamboo pole with cradle on each side to carry two baskets of goods. One strike hit the man’s shiny bald forehead. Blood gushed out from a big hole in his head. The man crumbled to the ground.”

The interesting thing for Tuan was the reaction of people witnessing the horror, or the lack of one.

“People simply looked at it like nothing happened. No emotion. No pity. No worries for the man. ‘It’s okay if it’s not me’ was the attitude that reflected the efficacy of the control technique used by the VC.”

There were ten squatting toilets just outside the fences enveloping the camp. To get access to them, the prisoners had to report to the guard on top of his tower.

“You had to yell out loud the exact password: ‘Bao cao can bo, tôi xin di ngoai’ [Reporting to the officer. I would like to go out], and wait for his approval. If, for some reason, he ignored our request, or we missed one word, then bad luck. Sometimes he enjoyed torturing us out of boredom from his long hours.”

Outside of the toilet’s fences lay a vast space where vegetation slowly grew over time. Grass and small bushes were knee high. There were anti-personnel landmine signs posted along the fences. People who did the cleaning were very careful not to step outside the fence, according to Tuan.

There was a road outside the perimeter of the camp, and when his cell block went out through the main gate to go to work on the fields or the forest, Tuan would sometimes see curious civilians wandering nearby.

“So, I knew there was traffic outside the camp. About half a kilometer from the camp, we could see a train passing by during the late hours of the afternoon. During my existence in the camp, I always kept a low profile. It was crucial that nobody noticed my absence for a long period of time. I usually spent my time watching the tower overlooking the mine fields, and I noticed that the guard rarely looked in that direction because of the glare of the morning sun.”

Early one morning, Tuan reported that he had diarrhea and couldn’t go to work. He went to the infirmary for medicine and went back to bed.

“I rarely missed work because going to work could get you extra food for your stomach. I didn’t raise any suspicion by staying in bed.”

That morning, after roll call, after everybody had left for work. Tuan got out of bed, went outside in the back to get a deep end bucket and put in the bottom civilian pants and shirt that he had traded khoai mi to people who had visitations from families. He took what he called his “detection instruments” — the bucket in one hand, and in the other hand, a shovel.

“I approached the entrance of the toilets while watching the guard on top of his tower. He was distracted by something because he was looking down, maybe reading or writing. I kept quiet, advancing to the entrance. If he caught me not asking his permission, he wouldn’t be alarmed because I had the cleaning bucket and shovel. I would just beg for his forgiveness and try another day, But I was lucky. He didn’t see me going in the toilets.”

Tuan had previously studied very well how mines were detonated. He now moved swiftly and carefully, climbing over the fence before anyone could spot him on the other side.

“I was really lucky that day. Nobody was using the toilets. The guard didn’t look up. And I worked my way slowly moving from bush to bush, avoiding a direct view from the tower. It took me more than three tense hours before I could reach the outer fence of the camp. [There was] no explosion. I was still there, hiding in the tall grass, I heard lang after lang of prisoners coming back from work heading to the main entrance. It was like living in another world for me at that moment,” he recalled.

Once free, in the summer of 1985, Tuan discovered a smuggling ring operating from the coastal city of Bac Lieu. His mother gave him five ounces of gold and he escaped Vietnam on a boat for a seven-day journey on the South China Sea, which landed him in Malaysia.

He recalled the days leading up to his escape.

“My Mom had given me her ring for the deposit, and I went down to Bac Lieu to check out the info and the organization. I happened to meet one of the organizers who had served in the Airborne before. He gave me a spot on the boat with a condition to take care of his 12-year-old son and teach him English. I was supposed to reimburse him once we reached America,” said Tuan.

Tuan stayed in that man’s house by the river and went fishing with him for almost two weeks until the departure.

When that night arrived, a dozen people from Saigon descended upon the organizer’s house and were ferried by small fishing boat to a bigger one.

“The boat looked solid, medium sized, capable of transporting 50 people or more. When around 30 people boarded, I heard the engine starting. I was still waiting for the organizer and his son to board when the boat started moving. Something was wrong. He was one of the bosses and he was not on board yet,” Tuan recalled.

“The boat kept heading towards the Cong An Biên Phong outpost. Suddenly, I heard, ‘Plouf, plouf.’ Somebody jumped into the water. We were supposed to stop at the outpost and pay the bribe to be allowed to continue to the opening of the bay to the ocean. But the boat was not slowing down. Someone took control of the boat and sped it up. We heard many gunshots, but no boat was following us. We spent seven days traveling toward the intended destination, the Philippines, but somehow reached Malaysia instead.”

Those aboard still had water, food and the ship had fuel when we reached Pulau Bidong Island. The ocean had been calm, according to Tuan. The seas not rough. And they were often escorted by pods of dolphins.

“It looked more like a vacation trip than a life-or-death adventure,” Tuan said.

One of the reasons the boat made it to Malaysia, Tuan said, was that, among the many ex-military aboard were Vietnamese Navy mechanics.

“Our boat was in excellent shape,” he said.

Tuan’s thoughts now turn to his mother, who was a fervent Baptist.

“Mom told me she prayed day and night before my trip, and after she got news from me [from Malaysia], she believed in miracles. She told me God responded to her prayers. I don’t recall her being religious before April 30th, 1975” [the fall of Saigon].

Sungei Besi Transit Camp — Tuan is second from right. (Photo courtesy Anh Tuan Tran)

The refugee camp at Pulau Bidong was run by the UNHCR (United Nations High Commission for Refugees). While it wasn’t home, Tuan opined that it could have been a lot worse.

“The UN camp was not really good, but compared to VC re-education camps, it was paradise. No control over mind and body. No self-critique sessions. No attitude watching. No indoctrination. No spying on each other.”

“For those who didn’t have overseas relatives to receive parcels or money, they were a little bit hungry, but they were not starving like in VC camps. In VC prisons, our daily portion was so little that, after a while, we dreamed only of food. We were obsessed with food. When we received our portion of rice, one guy swallowed it so fast he didn’t even chew. Another guy made small chopsticks and spent hours picking up each grain of rice with those chopsticks to savor the sweetness of the grain, to prolong his meal and make his hunger disappear.”

“At the UN camp you were free to do whatever you wanted. You were free to wander around the island. You were free to do any business you wanted. One guy set up a spot where he could make money cutting hair while waiting for resettlement,” Tuan said

Mealtime at the Ecole Francaise in the UN camp. Tuan is first on the right in the back. (Photo courtesy Anh Tuan Tran)

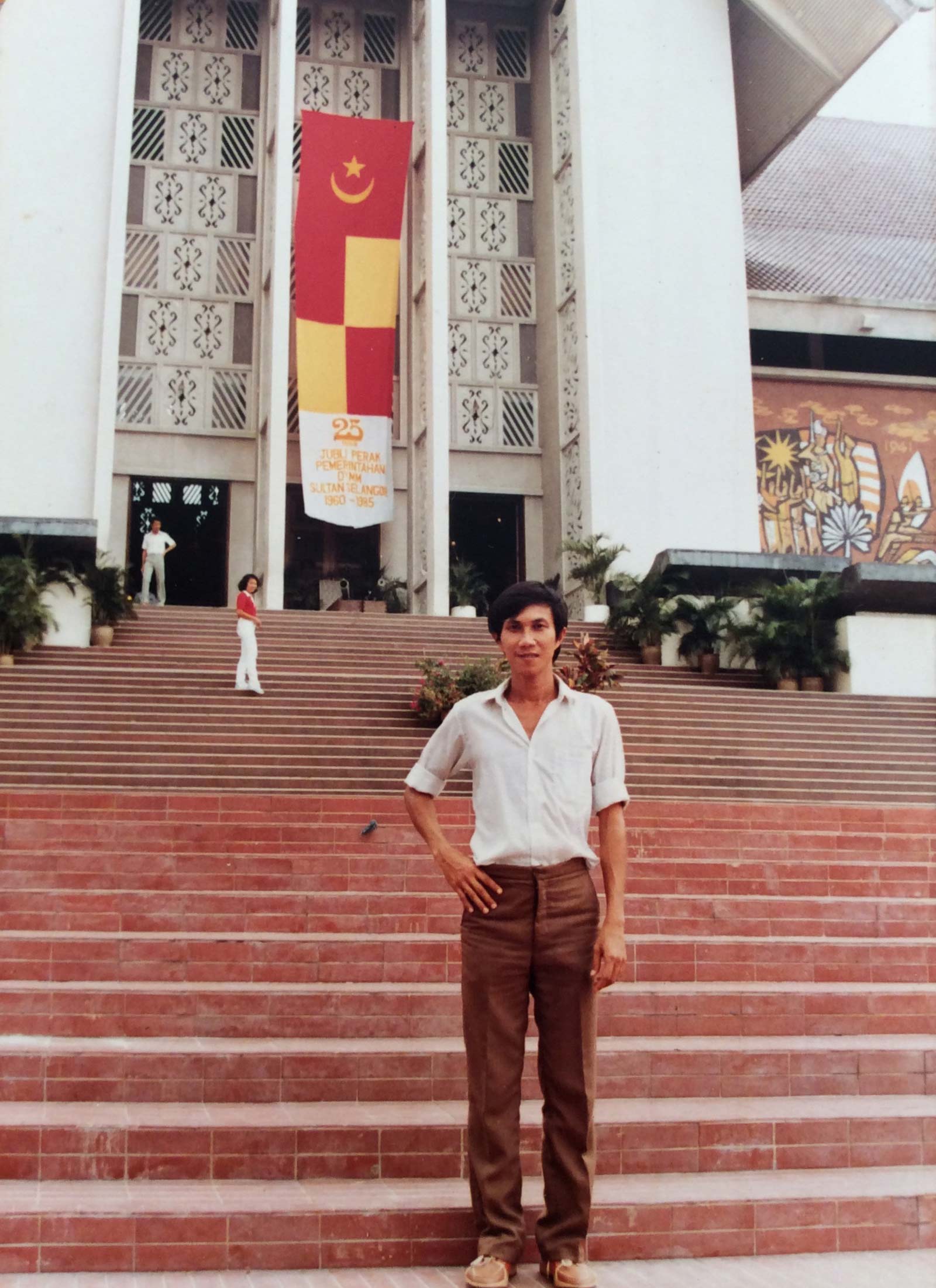

Tuan visiting a museum in Kuala Lumpur. (Photo courtesy Anh Tuan Tran)

Sungei Besi Transit Camp — Tuan is second from right. (Photo courtesy Anh Tuan Tran)

Tuan spent his days teaching French in the école française to the people who would settle in France, and as an interpreter for US and Canadian delegations when they came to the island to interview people for acceptance for resettlement.

“Pulau Bidong woke up to the sounds of music from the loud speakers. The familiar song was “Bien Nho” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CowW8pRypHc), sung by Khánh Ly in the 60s. Then came the newsletter, weather and announcements of the day. People ate their instant noodles and headed to their activities on the island. Those who had money could enjoy all sorts of breakfasts in the makeshift little market: pho, xoi dau xanh, xoi dau phong, banh mi thit. All kinds of exotic foods. Somehow people managed to smuggle in materials to even build a bakery to produce fresh baguettes,” Tuan remembered.

The UN supplies consisted mostly of instant noodles, rice, tuna fish cans, once in a while, fresh eggs. But people could have access to all kinds of food if they had money. Even the forbidden pork meat.

“You got into big trouble if you were caught smuggling or eating pork by Malaysian authorities [since Malaysia is chiefly a Muslim country and Muslims are forbidden to eat pork].

“Depending on their skills, people worked at various jobs on the island. There was sick bay “hospital” where you could get first aid, facilities where you could learn English, une école française overseen by a French adviser from the French Embassy in Malaysia.

The UN administrative building was where important events happened, according to Tuan: “Letters, money order deliveries, UN delegation interview sessions. The security was handled by ex-military volunteers. Some people built their own living places and sold them to newcomers when they were about to be resettled.

“When loud speakers announced the arrival of a new boat, people poured to the beach‘s “Jetty Bridge” to watch newcomers with their belongings coming to the island. They would give first-hand information about themselves before being processed into the system.”

“That was where VC infiltrators were denounced, and bad element factors were exposed. This provided crucial information for the delegations when they interviewed for resettlement later,” Tuan said.

UNHCR Camp Malaysia Ecole Francaise — Tuan’s future wife Hoa, sixth from left. (Photo courtesy Anh Tuan Tran)

He remains astounded that, instead of the closest thing to paradise Pulau Bidong was after the communist re-education camps, some people still use today’s social media to say negative things about the island.

“When you search Pulau Bidong on the internet, you stumble upon words like ‘Evil Island.’ I don’t know where that comes from, but it’s not the truth. Far from it. It should be called ‘Rebirth Island’ because it was the gateway leading to freedom where you could regain your dignity. Where you were allowed to be yourself again, and, after resettlement, you could rebuild your future, your life.”

Sungei Besi Transit Camp — Tuan on the far right. (Photo courtesy Anh Tuan Tran)

Because of his background, he was on a US bound list. However, he was told the people on the US list had just left. The next list would be processed in four to six months.

“When the Canadian delegation came a month later, and the official offered to resettle me in two months’ time, I could not say no, especially when French was one of the two official languages of Canada.”

When the boat people landed on Pulau Bidong, they were allowed to request to be interviewed by the US, Australia, Canada and France delegations. Usually, if refugees wished to be resettled in one of those countries, they had to have relatives there already. If not, they had to wait to be interviewed and accepted for resettlement.

“The problem was that those delegations only showed up once or twice a year, and if for some reason you got rejected because of discrepancies in your files, or dishonesty, you could easily spend five or ten years at the camp,” Tuan said.

“One guy made a big mistake by declaring that he killed such and such VC officials in raids he was part of. He was a frogman in the Special Forces. The interviewer was a young civilian female diplomat who didn’t think that this man was a hero because he killed many people and took pride talking about it. He was rejected by almost everybody after that. That’s why, when you have an opportunity to go, you grab it. That was the general sentiment in the camp,” he added.

Anh Tuan somewhere in the crowd of fellow employees at Bombardier Global Express Bay 4 ,Toronto 2017. (Photo courtesy Anh Tuan Tran)

Anh Tuan Tran grabbed his opportunity in January, 1986 when he was sponsored by a family in Kitchener, Ontario, Canada. He soon made his way to more cosmopolitan Toronto and eventually found work in the airplane manufacturing field. First with McDonnell-Douglas, where, between 1989-1995, he worked as a Wing Tank Mechanic on the company’s MD-80 and MD-11. Four years later, he again found work as a Wing Tank Mechanic for the Canadian airplane manufacturer Bombardier Aerospace, working on the company’s business aircraft fuel and vent systems for its Global Express 5000, 6000, then the Global 5500 and 6500. He retired in 2019.

Tuan, who stresses that he was living “au jour le jour” [day to day], says, “I rarely tell people about this. Imagine you are stuck in a desperate life that is going on forever. No `light at the end of the tunnel’ like you Americans say.”

Having lived through hell, today Anh Tuan Tran cherishes the freedom Canada has blessed him with, and the happiness that his family surrounds him with.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR — Marc Yablonka is a military journalist whose reportage has appeared in the U.S. Military’s Stars and Stripes, Army Times, Air Force Times, American Veteran, Vietnam magazine, Airways, Military Heritage, Soldier of Fortune and many other publications.

Between 2001 and 2008, Marc served as a Public Affairs Officer, CWO-2, with the 40th Infantry Division Support Brigade and Installation Support Group, California State Military Reserve, Joint Forces Training Base, Los Alamitos, California. During that time, he wrote articles and took photographs in support of Soldiers who were mobilizing for and demobilizing from Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom.

His work was published in Soldiers, official magazine of the United States Army, Grizzly, magazine of the California National Guard, the Blade, magazine of the 63rd Regional Readiness Command-U.S. Army Reserves, Hawaii Army Weekly, and Army Magazine, magazine of the Association of the U.S. Army.

Marc’s decorations include the California National Guard Medal of Merit, California National Guard Service Ribbon, and California National Guard Commendation Medal w/Oak Leaf. He also served two tours of duty with the Sar El Unit of the Israeli Defense Forces and holds the Master’s of Professional Writing degree earned from the University of Southern California.

Leave A Comment