The Escape of Anh Tuan Tran: Part One

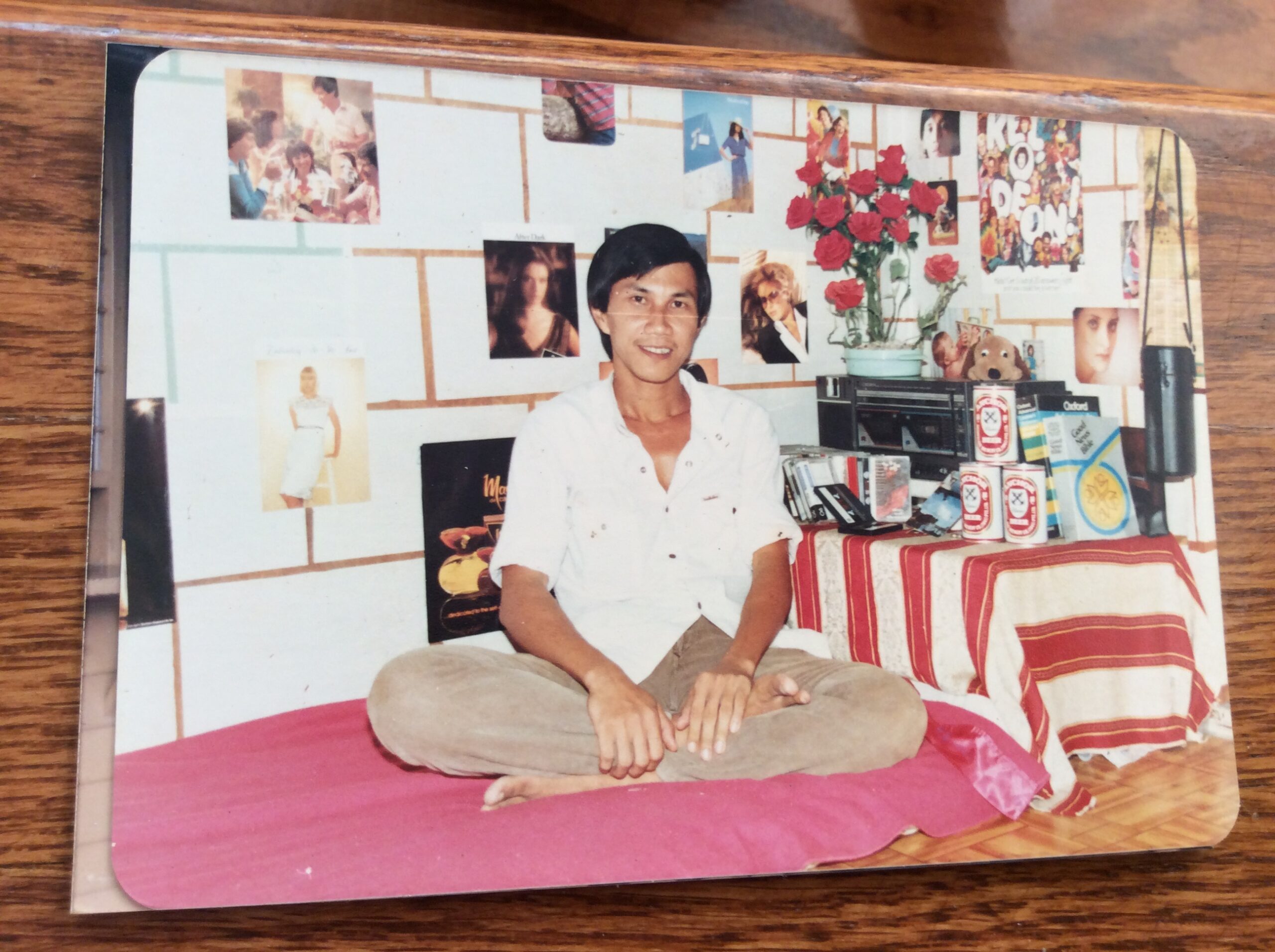

Anh Tuan with his RVN Marine unit seated for their graduation photo. Anh Tuan is second from left in the second row with arm on elbow of fellow Marine. (Photo courtesy Anh Tuan Tran)

By Marc Phillip Yablonka

Author and Military Journalist

As Americans, we have tended to look at the Vietnam War through an American lens. Concerned for ourselves as a nation, whether we fought in the war or protested it from the safety of the American heartland, we have tended to think about that long ago conflict as only ours. But there was another prism through which we might have been looking all along. That of the people whom we had sworn to protect: the people of South Vietnam.

One such person was a Republic of Vietnam Marine who also fought for his country and paid a heavy, heavy price: Anh Tuan Tran.

After graduation from Truong Bo Binh Thu Duc (Officer’s Infantry School in Thu Duc) in 1972, Tuan joined the Vietnamese Marine Corps and was assigned to C Recon Company, HQ battalion of the Vietnamese division, operating in Quang Tri Province as 1st Lieutenant, reconnaissance squad leader.

The whole division at that time consisted of three combat brigades, with one recon company, one artillery battalion, one medical company for each brigade, with the Vietnamese Airborne Division forming the first line of defense against the North Vietnamese Army.

“Because I was on the front lines, being in an elite force, I was always ready for any enemy movements. My recon company was the eyes and ears of the 369th Brigade. Depending on the orders from HQ, we frequently penetrated enemy territory to collect intel,” Tuan said from his home in suburban Toronto.

He was stationed at and around Dong Ha, Con Thien, right next to the DMZ a full two years after President Richard Nixon’s “Vietnamization” policy, which severely limited American involvement in Vietnam.

In early February 1975, (two months before the fall of Saigon) Tuan’s unit had orders to transfer its position to the local regional forces. From Quang Tri Province they moved to Da Nang to defend the city. Upon arrival, Tuan and his team were under heavy artillery bombardment from the mountains. Their mission was to penetrate enemy positions to locate and report coordinates to RVN Marine artillery units, and to return fire.

“My team had to infiltrate at nightfall. Ascending a high observation point, I tripped on a booby trap. The grenade exploded and I didn’t feel my leg. Everything went dark; my NCO had to transport me back to HQ on a makeshift hammock.”

“That was a very scary time. I was not afraid of dying, I was afraid of living the rest of my life as an amputee. I was so young. I’d hardly lived my life at all,” Tuan said.

He spent three days at the triage center of the medical team and was transferred to the Central Military Hospital in Benh Vien Duy Tan, adjacent to Da Nang Air Base.

“One night there were rumors the city was going to fall. Around midnight, the last flight of a C-130 to Saigon took off with only heavily wounded aboard.”

“One guy next to me bandaged his head and was carried away to the plane. I was not that quick thinking and remained at the hospital.’

The next day, a Marine GMC truck took Tuan back to the Marine headquarters medical unit located near Bai Bien Non Nuoc Beach. An Airborne GMC came to pick up their own. The hospital slowly emptied out. Everybody else was on their own.

For Tuan, that meant evacuation at the beach.

“Every one of us was ready. We all looked out towards the ocean. At dawn, lights appeared, revealing three ships on the horizon: one big ship and two smaller ones. The two smaller ones moved slowly to shore. Suddenly, the sea came alive. A strong gust of wind sent rafales of high waves to the shore. Battalions upon battalions lined up in columns ready to board,” Tuan recalled.

“But suddenly, far up on the highway appeared three M113 armored carriers, one speeding towards the Marines’ columns on the beach.” When it breached the security perimeter, the Marines sent warning M79 shots. The M113 returned fire with its M60 on board, sending the Marines scattering all over. It continued speeding towards the ocean, entering the water, and started floating towards the ships, but sank after the waves overcame the vehicle. The guys who drove it thought their amphibious light tank could operate on the sea. Poor guys! Ignorance does kill,” he said.

“Someone must have leaked the evacuation information to the populace because suddenly, after the M113 arrived, thousands of civilians, women, and kids with their belongings, came running to the beach; they stepped over each other, fighting, creating chaos. The sound of artillery shells exploding got closer and closer, finally landing on the beach, creating carnage, killing a lot of innocent people.”

“It was a `sauve qui peut’ situation. ‘Chacun pour soi-meme,’” [run for your life. Each one for himself], Tuan said in his second language. “Total panic. Everybody jumped into the water, trying to swim to the ship a few hundred meters away from shore. I got rid of my crutches and jumped into the water, trying to get in sync with the waves, pushing upwards with my healthy leg. When a wave came, I went up with it. When it passed, I landed on the ocean floor. I waited for the next wave to jump up again while edging slowly towards the ship. I remember my feet not touching the sand but something soft many times. It must have been somebody who had drowned underneath me,” he said.

Half way, Tuan grabbed a floating device someone had made from a poncho.

“Without it, I don’t think I could have reached the ship. So many people were climbing aboard that it became heavily overcrowded and started to be stranded. I was lucky to have my Marine uniform on top of my hospital gown,” he said, recalling that one Army captain was sent back to the beach because his ship was for Marines only.”

That ship transferred Tuan and his fellow Marines to the bigger ship, which then transported them to Phan Rang. It then went back to Cua Viet to rescue more Marines.

Tuan’s thoughts now drift back in time to the Tet Offensive of 1968 and its aftermath.

“When the VC occupied the city of Hue and massacred 3,000 people who were found buried in mass graves, whenever people saw or heard that government troops were leaving, they knew that NVA was going to seize the opportunity to move in.”

“And if the VC came, and you didn’t get out right away, you would never have the chance to leave. So, there was an exodus of people with their belongings crowding all the highway and routes going south. Dai Lo Kinh Hoang (Horror Highway) which happened when VC artillery shells targeted fleeing people on Highway 1, Quang Tri Province, killing thousands,” he said.

Years later, after having escaped Da Nang on the Marine ship, Tuan had this to say:

“Exiting the ship, I followed the flow of people heading south, using all means of transportation: walking, busing, riding on Lambretta 3-wheeler scooters, Camionnettes [minivans]. At that time, people usually gave free access to injured soldiers. That’s why I was wearing my Marine uniform shirt with the hospital pajama pants,” he said.

When Tuan reached the checkpoint at Bien Hoa, he put on his officer insignia epaulettes, was saluted by a Marine MP, and driven to Le Huu Sanh Hospital inside Rung Cam Marine Base, Thu Duc.

The surgeon removed shrapnel from Tuan’s leg and told him he was lucky not to have an infection, and that the salt water during Tuan’s swim to the Marine vessel might have kept his leg from being infected.

“I stayed until the end, and I walked home before the VC came and took over. During my stay at the hospital, I was informed that my unit was stationed at Vung Tau, but because my doctor did not release me, I could not go back. Who knows what would have happened if I had gone back?” he asked, remembering that most of his fellow Marines in the final days of the war used small boats to go out to sea and were picked up by the US Seventh Fleet.

In the last 46 years, Tuan has had ample time to reflect on the final outcome of the war in Vietnam.

“Looking back, the two main factors that decided the outcome of the war came down to the structure, the making of the soldier. First, the NVA soldiers’ mental state had been nurtured in an environment of blind obedience to the Communist Party since birth. They believed that the south suffered under an oppressive regime, and they were willing to sacrifice their lives to liberate the country. Each NVA soldier was brain-washed every day by the commissar political adviser. He feared his own peers would report any weakness. They called each other “Dong Chi,” which meant `same vision, same goal.’ They used any means — lies, threats, misinformation, torture, even killing — to reach their goal,” Tuan believed. “They were robot soldiers.”

“By contrast the South Vietnamese soldier was influenced by his family, his humanity — he could not kill, mistreat elderly, women, children — and most importantly, he could think. He didn’t believe in propaganda. He knew right from wrong. That made him weaker than the robot soldiers who pushed through everything to achieve their goal,” Tuan said.

The second factor, in Tuan’s opinion, was the equipment.

“The robot soldier required minimum basics: food to survive and weapons to kill. Everything else was secondary. He wore sandals and a hat for protection. He required no salary. For one South Vietnamese soldier, you could produce 100 NVA soldiers; the ratio was always 10, 20, 50. or 100 to one in every battle. There must have been a reason why the South lost the war.”

Tuan expands on what he feels that reason was.

As soon as the NVA and VC entered a city, with the help of local followers, they took control of all government facilities, and started patrolling the streets with propaganda themes on loudspeakers. They soon requested people to register their household and encouraged denouncing `anti-revolutionaries’ and reporting all enemies of the people.

“People were confused and scared,” he added. “Who was considered the enemy of the people? Would they be executed? Would there be a new Hue massacre but on a bigger scale?”

A new order came the next day, advising all military and government employees of the “old regime” that they would be pardoned if they voluntarily registered to undergo re-education classes: from Private 1st class to NCOs, three days; for junior officers, ten days; for captains up to generals, six months, according to Tuan.

“They had to bring their own food and clothes, `Failing to do so would face serious consequences,’” the notice said.

“I watched the first `catégorie,’” Tuan said in French, “go and come home. After all, we junior officers were only small potatoes. It would be only ten days, plus the neighbors were watching. The communists were very good at sowing fear to control people. They were masters at lies and misinformation.”

“I showed up at lycée Jean-Jacques Rousseau, my old high school, the pickup point for District 1 in Saigon. I saw some of my friends from university. When we filled out the paperwork, we were told that they knew everything about us, that they seized the Ministry of Defence, and had all the documents. They just wanted to confirm if we were honest to confess our crimes to the people. [They told us] we would be punished if we were not.”

Tuan and the others were organized into ten-person teams with one designated leader to be responsible for each team.

“That night we were loaded into covered Molotov vans. After hours of driving on suburban roads, they made us sit down in columns in a big industrial yard. Then they loaded us into the belly of a big transport ship. I will never forget how dark and suffocating the space was when they closed the lid above us,” he remembered.

“After a few hours, suddenly they opened the lid and released us into the yard to be head-counted again. Then we were loaded back into the Molotov trucks, and the convoy headed back to the city and drove northeast. This time the guy sitting in the back poked his head out from time to time and gave us the information about where we were going.”

At dawn they reached a big walled compound.

“I know this place,” one guy said to Tuan. “It’s Thanh Ong Nam.”

Thanh Ong Nam was the ARVN military civil service base in the Hoc Mon District, in the outskirts of Saigon, not far from the now famous Cu Chi tunnels in what Tuan referred to as “VC country.”

Tuan very soon realized that what he and the others were told would occur was light years away from the reality.

“In the morning, we had to exercise for half an hour. After that, each group sat down in a circle. We started to introduce ourselves. Everyone was forced to express an opinion about the `revolution’, the crime we committed towards the people, if we had any regrets, etc. All of us were exhausted and sleepy after the night before, but we had to keep going.”

“In the evening, the political teacher visited each group to answer questions. The most important questions were, `Are we going home after ten days?’ `How long are we going to be here?’”

They were told, “As long as you study good, you have a chance to go back to your family.”

“He never defined the word ‘good,’ and that was the only time he showed up to talk to us for the next seven days; I knew then I wasn’t going to be home after ten days like they said in the announcement. Like thousands of others, I was being duped by a cunning adversary,” Tuan realized.

Many years later, at an RVN Marine reunion in California, one of Tuan’s friends told him that he was transferred all around the country, camp after camp, doing hard labor for more than six years. But because he was a junior officer, he was not taken to camps situated in the north like the more senior ones.

“That made me remember the first time we were loaded into the cargo ship. It was a mistake. That ship was for those who were destined to go to camps far away in the north.”

Tuan started to plan his escape

“The longer I stayed, the harder it was going to be to escape,” he told himself. “People started observing each other. They started changing. They started to adapt to reality. They started reporting on each other.”

The prisoners were not permitted to go outside their barracks after 8 pm.

“Only NVA soldiers in their loose green uniforms were moving around. Some went outside the compound through a door with a light bulb shining into their faces and said some ‘mot de passe’ [password] to the armed guard on duty,” Tuan recalled.

“On day seven, earlier in the evening, I noticed an NVA uniform being left to dry on a clothesline, outside the next building, just outside our perimeter. It was still there when darkness fell at 8 pm. I told my team leader I had to go to the toilet outside. I waited for a few minutes and then climbed over the concertina fence surrounding our barracks to get the uniform. I knew that nobody expected a move like that in the early days. There was no light except the moon, so I strolled around like an NVA soldier, making sure not to get too close to anyone around. But I couldn’t go through the door. The armed guard would know right away when he looked at me, I only had the uniform, no sandals. (The NVA footwear), no NVA pith helmet. I could not speak with the northern accent, and I didn’t know the ‘mot de passe.’”

Tuan wandered around for a while, thinking and following the wall until he found a lower portion. Seeing nobody around, he managed to climb over and find himself on the other side.

“My first thought was to get away as far as possible. If someone discovered my absence and reported me, then the farther away the safer.”

There were people walking on the streets, living life normally, and Tuan felt safe in his NVA uniform. There was a food stall on wheels selling sugar cane juice with ice. I approached and ordered a glass, trying to imitate the northern accent, pretending to be from the north. By the look of the girl handing me the glass of juice, I knew she thought there was something funny about this guy with his funny accent. At the time it didn’t matter. I was enjoying the first cold drink I had had in a long time,” Tuan reflected.

“I asked her, `Which way to Saigon?’ She pointed her finger to the street leading to the highway, still with her curious look. I paid her with the money I hadn’t had the chance to spend since I showed myself to captivity, and started moving in that direction. The farther away the better.”

As the time reached nine o’clock the streets in the town began to empty of citizens.

“Little did I know that there was a curfew at 10 pm. I was concentrating on walking fast, without raising suspicion. Some dogs barking when I walked past a house made me feel uneasy. There was nobody outside on the road now. So, I took the chance to put as many kilometers as I could between me and the compound.”

“Suddenly, out of nowhere, three silhouettes appeared, pointing AKs at me. ‘Dong Chi! Dung lai! (Comrade, stop!). Where are you going at this hour? Where is your unit? What are you doing in this area?’ [They were speaking] in the northern accent. I couldn’t answer any of those questions.”

“They pulled me into their checkpoint and started questioning me. They discovered I was a fake. More guys came. They decided to tie me up and wait for their superior. He came and started the interrogation. After a while, he concluded that I was a dangerous enemy trying to infiltrate and murder them.”

For two or three days, Tuan endured questioning and torture. They woke him up every four hours and tried to get him to confess his intention. They put him in a cage so small that he got cramped up and couldn’t move around.

“I gave them a fake last name and address so they couldn’t link me to my escape, but between beatings, I forgot what I said before. In the end I had to tell them the truth. I thought that they would take me back to the compound, but they transferred me to the civilian police.”

Tuan was transferred to the famous Kham Chi Hoa city prison, an octagonal prison built by the French that was then being used by the communists.

That would not be the last time Anh Tuan Tran ran afoul of the communists, however. When asked how many times he escaped, he listed his tribulations thusly:

“Two times. The first time from the Hoc Mon compound; recaptured; jailed in cage at the smallest level of government, Xa Phuong. Then next level up, Quan District prison; city prison Kham Chi Hoa.”

He then spent more than three years in another communist re-education camp, Suoi Mau Bien Hoa, from which he escaped. He traveled to the Central Highlands city of Pleiku in an attempt to walk through the jungles of Laos to reach freedom in Thailand. Unfortunately, he was captured by Pathet Lao communists and brought back to Kontum.

When Tuan was caught by the NVA unit, he was interrogated and beaten.

“But I guess because they didn’t have a holding place, or they didn’t really consider me dangerous (I didn’t have any weapons, didn’t offer any resistance), they delivered me to the local VC in the morning.”

Tuan related how he was held in a cage like an animal and questioned for several days by a lower government official, “Cap Phuong Xa” in Vietnamese.

He was then transferred to the prison of the higher government office, “Cap Quan”. This very old and solid district prison was built during the French era.

“I was sent in a sort of holding structure in concrete. I remember it had a big steel door leading to an alley with a row of ten double cells, one on top of the other on both sides. The cell was very small and had a very low ceiling. It had one small opening for air. It held six prisoners. Once inside, you could not sit up straight. You could only crawl in and lie down next to each other. It was like the six of us were inside a big drawer. It was so claustrophobic that I had to fight my fears to stay sane. The prisoners were from common criminals (theft, burglary, assault) to political ones (anti-revolutionary denounced by someone or defying re-education orders). Each cell had one large ammo box for prisoners to urinate in. It was emptied two times a day at meal time. Prisoners were allowed outside for a half an hour during lunch and had to ask permission from guards to go to the toilet. Every newcomer had to spend up to two weeks in these suffocating, humid, terrifying holding compartments before being released to the general population in bigger cells,” Tuan recalled.

“At lunch time, the cook, also a prisoner, brought in a big pot of rice and put one long handled spoon of rice into each prisoner’s holding container.”

Tuan did not have anything to receive the rice and had to trade one third of his portion for a piece of nylon cloth to hold the rice.

“In the evening, after dinner, the guard locked all the compartments and the principal door. He resumed peeking into the compartments the next morning. I was trying to deny the reality of my present situation, and think of something pleasant and happy, like when I was a student at the University of Dalat before being drafted.”

“Suddenly, I smelled smoke. I started panicking, thinking about being roasted in that hole. One of my cellmates yelled something and pulled out a cigarette made of crude tobacco rolled into a small piece of newspaper. He reached his hand over to the next cell through the steel bar door and retrieved some sort of cotton shoelace with the embers in one end. He then lit his cigarette and passed a lighting device to the next cell.”

“Thus, the ember lighting device was circulated around through each cell. People started enjoying their smoke inside the prison. We risked being sent to the shackles room if we got caught. Still people liked to defy prison rules. Someone succeeded in smuggling in matches. So started that magical event,” Tuan said.

The next day, he joined in the fun by exchanging half his rice portion for one cigarette.

“That was the most enjoyable moment I had during my time in that prison. The effect of that smoke sent me through the clouds. I felt dizzy and out of this world.”

During Tuan’s captivity, he realized that, although they also considered him an enemy, the VC of the south were less aggressive, less cruel than the NVA from the north. They often told him that he deserved to starve to death for being the enemy of the people. They took turns beating him up even when he didn’t resist.

In contrast, the VC tried to be more aggressive in appearance, but they gave him food and water and didn’t show much animosity as their counterparts from the north.

“In the early days, the guards that the officials used were often young guys without education. They just gave them an AK, told them what they wanted, and they [the young NVA] executed [the task] perfectly with enthusiasm,” Tuan believes.

“They considered prisoners sub-human. They treated us very harshly. The rule was when we approached a ‘comrade citizen,’ we must stand still, one meter away from them, ask for permission to speak, and only move when he gave us permission. Imagine how you would feel when a stupid kid with the AK has so much power over you!”

One of the prisons Tuan was subjected to, Chi Hoa City Jail, was a prison for civilians. But during the Vietnam War, the VC turned it onto a holding jail for common criminals, but mostly political dissidents.

“Anyone considered dangerous or simply anti-revolutionary (Phan Cach Mang) was put there. In my cell, most prisoners were young, but there were also older ones. In my group there was one grey-haired gentleman in his sixties who was a long-time retired Airborne captain from the French Legionnaires, one intellectual looking old man with wire rim glasses, who must have been a professor or a high-ranking government employee. There were a few airmen, [including] a helicopter pilot, a group of young Airborne officers, who were very close knit. The majority were denounced by neighbors or local informers. We were often interrogated many times a day and encouraged to spy on each other. That’s probably why most of us kept to ourselves,” Tuan feels.

The daily routine in Chi Hoa was very mundane and forceful.

“There was “diem danh” (roll call) two times a day, in the morning and in the evening. Between hours, patriotic and revolutionary songs. I think [my] survival instinct outweighed any ideological thinking. If you are forced to save your own skin over the others, either to have more chance to be released, or to simply have better treatment, day after day, month after month, year after year, you will succumb to it. Communism is expert in controlling people’s minds and bodies.”

To him that explained why every Special Forces team sent to operate in northern regions controlled by communists was apprehended right away when they ventured into the populace.

“Everybody knew everybody, everybody spied on each other. You could not have chicken while other people around you could only afford rice mixed with ‘khoai mi’.”

In jail, the prisoners were deprived of any notion of time. Their days were spent waiting for hot water and food.

“I remember feeling a sharp pain in my stomach when the leader of the group failed to divide the rice portion equally and had to take back one spoonful from each of the portions he’d already distributed to fill up the three last ones,” Tuan said, stating that there were two categories of prisoners in his cell, the ones who received parcels from their family and the ones who were ‘mo coi’ [orphans].

“Unlike the privileged ones, we orphans were always looking forward to receiving our very small portion of rice every day. Over time, we got so hungry that, at lunch time, all eyes were on the guy who was in charge of distributing the rice. We gathered around in a circle with our containers in front of us and watched closely the hand that delivered the precious substance that sustained our lives. When the pot was empty and there were still two or three portions to be filled, he had to take back a spoonful from each portion already filled to make the last ones. People groaned, and some protested.”

“You are taking too much from mine!” “You are taking too little from that guy!”

“Every grain of rice counted in that fight for survival. You got weaker and weaker, and soon food was the only thing that occupied your mind. No more thoughts of rebellion or anything else. Everyone exposed their true self: the once proud pilot became humble, obedient towards the kid, ‘can bo’, when he gave orders from outside

the cage. The privileged formed their own group and guarded ferociously their treasure (food, medicine, clothes). And they usually had “serviteurs” [servants] to protect and entertain them,” Tuan said.

“There was one guy who could tell stories, the whole set of 12 books of ‘Co Gai Do Long’, a very popular martial art book series. Every night the privileged people gathered around him and listened to him for hours. There was another guy who could perform crackling massage moves on you for a piece of raw sugar. Food equaled power in there,” Tuan said.

In the corner of each cell, there was a squatting toilet where people could wash themselves with a bucket of water if they could bribe the prisoner “room chief” (truong phong), according to Tuan.

The “chief of the room” was designated and trusted by the VC guard and was responsible for almost everything, from distributing meals and water to controlling the mood of prisoners. He was the one who reported directly to the can bo. He didn’t get transferred as often to other rooms or pavilions for no reason like the rest of us.”

“I think we experienced skin disease in this time period because of malnutrition and close contact living.”

Tuan endured that life until he was transferred to the Suoi Mau re-education labor camp in Bien Hoa Province.

PART TWO: In the Sentinel’s October issue — life in the Suoi Mau re-education labor camp and how Tuan made his escape to a new life.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR — Marc Yablonka is a military journalist whose reportage has appeared in the U.S. Military’s Stars and Stripes, Army Times, Air Force Times, American Veteran, Vietnam magazine, Airways, Military Heritage, Soldier of Fortune and many other publications.

Between 2001 and 2008, Marc served as a Public Affairs Officer, CWO-2, with the 40th Infantry Division Support Brigade and Installation Support Group, California State Military Reserve, Joint Forces Training Base, Los Alamitos, California. During that time, he wrote articles and took photographs in support of Soldiers who were mobilizing for and demobilizing from Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom.

His work was published in Soldiers, official magazine of the United States Army, Grizzly, magazine of the California National Guard, the Blade, magazine of the 63rd Regional Readiness Command-U.S. Army Reserves, Hawaii Army Weekly, and Army Magazine, magazine of the Association of the U.S. Army.

Marc’s decorations include the California National Guard Medal of Merit, California National Guard Service Ribbon, and California National Guard Commendation Medal w/Oak Leaf. He also served two tours of duty with the Sar El Unit of the Israeli Defense Forces and holds the Master’s of Professional Writing degree earned from the University of Southern California.

Leave A Comment