The Chinese Gotcha

Editors Note: This article is an expanded version of an account in James Lockhart’s memoir The Luckiest Guy in Vietnam, published in by BookBaby in 2018

By James Lockhart

Our camp, adjacent to the village of Long Hai, Vietnam, was in an area that some might have called “pacified.” We didn’t use that term because the Viet Cong, hiding in the nearby mountains, would periodically try some nasty trick—a few mortar rounds, a mine, some automatic weapons fire at a helicopter—but nothing we considered serious. And although we were a Special Forces unit, we needed a relatively quiet area to perform our then-secret mission: training infantry battalions for the newly expanding Cambodian Army. It was January 1971, and we were in full swing with the training.

Camp Long Hai was polyglot-based, with four languages being spoken. Of course, the U.S. Army personnel spoke English. The Cambodian soldier-trainees communicated in their native language, Khmer. (Some of the officers spoke French, but we won’t count that.) The mercenaries in one of our 100-man security companies were local Vietnamese. Surprisingly, the fourth language was Chinese, spoken by the indigenous ethnic Chinese—known as Nungs—comprising our second security company. Adding spice to this mixture would be an Australian Army Training Team, which would soon augment our Special Forces trainers.

Although some of the U.S. personnel knew a smattering of Vietnamese, none of us could speak even rudimentary Khmer or Chinese. This included the two Special Forces sergeants who supervised the security companies. As a result, we were entirely dependent on interpreters to communicate with our Cambodian trainees and both security companies. Generally, the interpreters were well qualified, having had extensive experience with Special Forces units. However, we never knew when one of them had a deficiency until it was manifested in some embarrassing—but never tragic—manner.

I had been assigned as the operations officer for our unit, which consisted of about 100 U.S. personnel. We had been training the Cambodians for just over two months, and we were still ironing out the kinks in the new program. We were simultaneously training four battalions of 512 men each, so we always had 2,048 trainees in camp at all times. My job was to schedule all of the training for each battalion, coordinate the training facilities, oversee the conduct of training, and recommend improvements to the overall program.

In addition, I had a responsibility that was not directly connected to training. In order to keep the local Viet Cong on their toes and from venturing too far from their mountain hideouts, we took some initiatives. First, we would fire mortars on known trails and streambeds at random times during the night to show that we were not passively waiting to be attacked. In that same vein, we formed a team from each security company to conduct nightly ambushes in the lower elevations of the mountains to discourage any nighttime movements by the VC. Although the security company teams did not work directly for me, I determined their ambush locations and the mortar fire targets for each night.

It was in light of my operational control of the ambush teams that I was assigned to correct a problem with their field techniques. Each night, the ambush teams would call back to the camp by radio to report their exact positions. We had one Vietnamese and one Chinese interpreter on duty to take the calls and translate the coordinates for the U.S. radio team to record. Somehow, the camp commander had learned that the ambush teams were reporting their locations in the clear, that is, without encoding them. This meant that if the local Viet Cong had radios—not an uncommon occurrence—they could intercept transmissions and determine where the ambush teams were located. This would not only reduce the teams’ effectiveness but also put them in real danger.

Jim Lockhart in 1971 at Long Hai, Vietnam, where he put his four-word Chinese vocabulary to practical use. (Courtesy James Lockhart)

Luckily, I had had a previous tour in Vietnam in an Infantry division and was well acquainted with a solution: a simple substitution code. Without delving too deeply into map grid coordinates for pinpointing locations, they can be accurately represented by six digits using numerals 0 through 9. With a substitution code, a key is created in which each of the numerals in the coordinates is changed to a different number. So if the ambush teams had the key and so did our radio team, the encoded coordinates could be transmitted by radio without fear that the Viet Cong could understand them even if intercepted.

It worked like this:

Actual map coordinates:

4 3 2 6 5 0

Substitution code key:

For each of these numbers:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0

Substitute these numbers:

0 7 4 1 2 3 9 6 8 5

Encoded coordinates:

1 4 7 3 2 5

Having set up a substitution code key, which would change periodically, I instructed the Vietnamese and Chinese interpreters on its use and directed them to teach it to their ambush teams. To make sure that the system was implemented, I had the Special Forces sergeant in charge of the Vietnamese security company, who had passable language skills, monitor the radio that night for compliance. I would verify that the Nung ambush team was using the code correctly.

That night, when the ambush teams were in place, I went with the Chinese interpreter to the radio bunker to monitor the Nungs’ location report. As it was being received, he recorded it, consulted the code key, and wrote down the team’s coordinates, which indicated that they were in the correct position. Then we left the bunker.

Outside, the interpreter was very surprised when I turned on him in a state of towering anger. I informed him that he was lying and that the ambush team had reported their location in the clear—without encoding it. At first, he denied it all but eventually admitted that I was correct. I explained that this was not only a serious tactical compromise of the ambush team but also a breach of trust with his employer. I also informed him that if any such transgression occurred again, I would march him to the Vietnamese Special Forces headquarters in our camp and enlist him in the Vietnamese Army, which would be a very disagreeable development for him.

To be fair, this individual had always been typical of the Nungs employed by Special Forces: capable and loyal. I treated the incident as a one-time lapse and not an ongoing concern. And after we came to an understanding about the use of the encoding systems, I had no hesitation about giving him my complete trust. In fact, we had several subsequent interactions, and his performance was impeccable.

How was this indiscretion unmasked by someone who didn’t speak Chinese? It’s complicated.

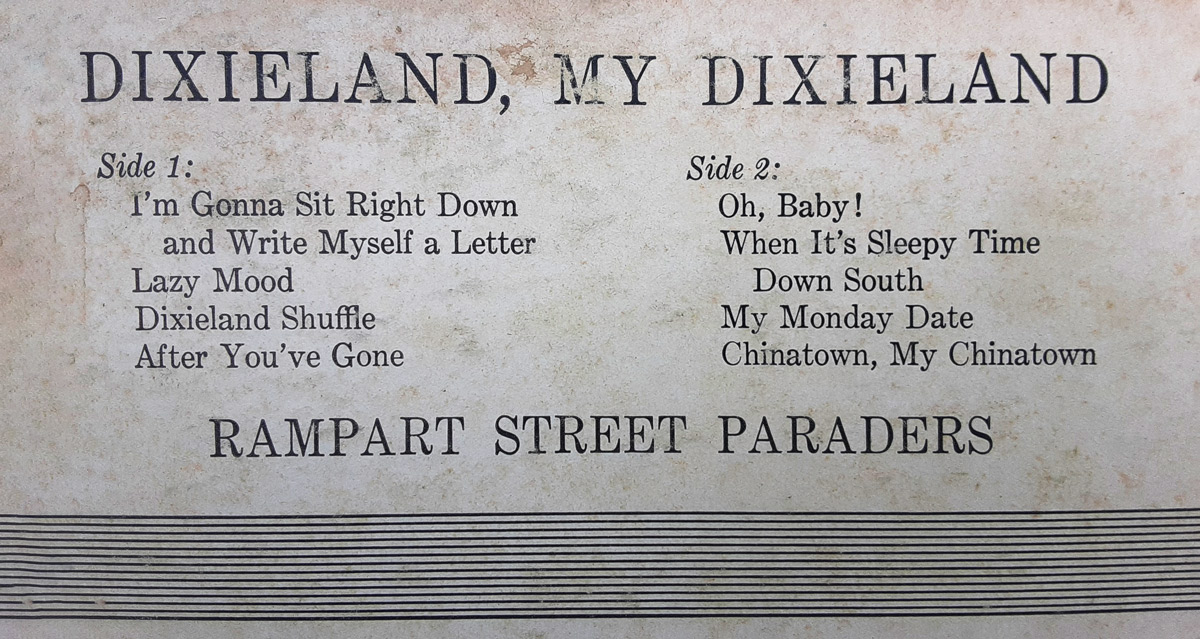

In high school, I played drums in the dance band. I had a complete drum set in my room and practiced there frequently. My favorite music genre was Dixieland, and that was the preferred type of LP album to play along with on my hi-fi—not stereo—record player. My favorite record was by the Rampart Street Paraders, and one of their songs was titled “Chinatown, My Chinatown,” which was a variation of “Dixieland, My Dixieland.” What made it into “Chinatown” was that the tempo at the beginning was counted off in Chinese. It sounded to me like “yit, yee, san, say,” which was clearly “one, two, three, four.” (Think Lawrence Welk.) Those words are still indelibly etched in my head from the repeated playing of that album.

In order to apply this imbedded memory to verify the ambush team’s encoding, I had to construct the code key so that the encoded coordinates for that night would include as many of the first four digits as possible, which, of course, were the limits of my Chinese vocabulary. This is illustrated in the example above. When these digits didn’t appear in the correct positions in the team’s radio report, I knew that they had not used the code to encrypt their location.

I was, and still am, amazed at how a dormant bit of insignificant knowledge can surface at a time of need, serve an important purpose, and then fade back into obscurity. I never revealed my methodology to the hapless interpreter.

About the Author:

James Lockhart enlisted in the Army in 1961 and was quickly promoted to sergeant. He volunteered for officer training and became an Infantry second lieutenant in July 1967. From March 1968 to February 1969 in Vietnam, as a lieutenant he led mortar and reconnaissance platoons and commanded an Infantry company. After completing airborne and Special Forces training he returned to Vietnam in late 1970.

In the next 18 months, as an operations officer, making significant contributions to the training of Cambodian Infantry battalions by Special Forces personnel. Subsequently, he served as an A-Team Leader, staff officer and company commander as well as Reserve Component advisor in Special Forces units before retiring as a major in 1982.

His awards include the Bronze Star Medal with V and two oak leaf clusters, Meritorious Service Medal with oak leaf cluster, Air Medal, Master Parachutist Badge, Combat Infantryman Badge, SCUBA Badge, Vietnamese Staff Service Medal and Cambodian National Defense Medal.

After retirement he worked for AT&T as a Technical Consultant and Account Executive. His last employment was 17 years with DeVry University as Associate Dean and Professor. He holds a bachelors degree in psychology and a masters degree in management. He published a memoir entitled The Luckiest Guy in Vietnam in 2018. James lives in southern California with Suzanne, his wife of over 35 years.

Love this story! It’s funny how the miscellaneous stuff that somehow embeds itself in our memory when we are young happens to come in very handy.