The 46th Special Forces Company — Part II

“If you can make one heap of all your winnings

And risk it on one turn of pitch-and-toss,

And lose, and start again at your beginnings,

And never breathe a word about your loss…

Yours is the Earth and everything that’s in it,

And — which is more — you’ll be a Man, my son!”

Rudyard Kipling, “If”

By SGM John Martin

Change of Venue – The First Days

I’m not exactly sure when I learned in Thailand that our B-detachments and A-detachments were not going to be deployed in Laos. However, the less than warm greeting of the embassy personnel when we first landed at Takli RTAFB, and the problems with our country clearance forewarned me that the future might not be as I had anticipated.

According to our pre-mission training at Fort Bragg, we had been formed to conduct interdiction operations against the Ho Chi Minh Trail from Laos. Instead, we were being deployed in Thailand, west of the Mekong River, with no mission statement to interdict North Vietnam’s infiltration routes in Laos and Cambodia. Pre-mission training left me with little information to anticipate what we were going to do in Thailand and how it would help the war effort in Vietnam. I remember the old vets saying, “You need to maintain flexibility and a good sense of humor. Don’t worry about the small stuff. It’ll work out.” I can’t tell you how many times those phrases ran through my mind every time my mission statement changed unexpectedly in the coming years.

By the time we were at our temporary quarters at Camp Pawai near Lopburi, Thailand, awaiting forward deployment to Laos, we were briefed that our mission had changed. Not only had our mission changed, our deployment location had changed. Instead of deploying into Laos, we were told our B-team, B-4610, and four A-teams would be deployed to Northeast Thailand, where we would build a SF fighting camp to include seventeen buildings, bunkers, and barbed wire fences. The construction would take place next to a reservoir formed by the Nam Pung Dam in a heavily jungled area 35 miles from the town of Sakon Nakhon. The dam was just completed in 1965 as a WWII war debt from Japan to Thailand, and had already formed a sizable reservoir lake. Since there were only high mountain forests before the dam was built, there were no close villages near the reservoir in 1966.

In addition, the three B-teams would be widely dispersed in Thailand while the 46th SFCA Headquarters remained in Lopburi. Our B-team, B-4610, would go to Nam Pung Dam near Sakon Nakhon in the northeast. B-4620 and its four A-teams would build Camp Nong Takoo near Pak Chong in central Thailand, and B-4630 would build Camp Carroll near Trang along the Thai border with Malaysia.

We were curious where our A-teams would be further dispersed as A-teams in Vietnam built and ran combat outpost camps in Vietnam along the many infiltration routes the North Vietnamese were using to infiltrate the less populated border areas of South Vietnam and further eastward toward the major population centers nearer the coast. It was unusual to have the B-team and four A-teams all in one camp, so compared to our deployments in Vietnam, this deployment to Nam Pung Dam was unusual. Adding to the confusion, we weren’t told what our follow-on missions would be after we built the camp.

It did work out, and we did contribute to the war efforts in Laos and Cambodia in a very significant way. What I didn’t understand at the time was the impact of manipulations and statesmanship that were closely controlled by the State Department, other government agencies, and the Thai government, who all had a wider perspective on the war in Vietnam and the diplomatic tectonics of Southeast Asia and the spread of Communism. Looking back now, I see the history of the 46th SFCA directly paralleled US involvement in South East Asia and America’s eventual withdrawal of its military strength.

The Situation

I’ve had to piece much of what I’m going to say based on three and a half subsequent years in Thailand and much background reading, but understanding why the 46th Special Forces Company (Airborne) stayed in Thailand requires a little knowledge of the situation in Laos and Thailand preceding our arrival.

To be sure, Vietnam was center stage in our interests in South East Asia. North Vietnam, with the help of their Laotian allies, the Pathet Lao, conveniently disregarded the restriction of inducing combat forces into Laotian territory. Their main purpose was to secure the areas adjacent to their supply routes from North Vietnam to South Vietnam. Originally conceived during WWII and later the French-Indochina War, this logistical network was continuously improved during the American experience.

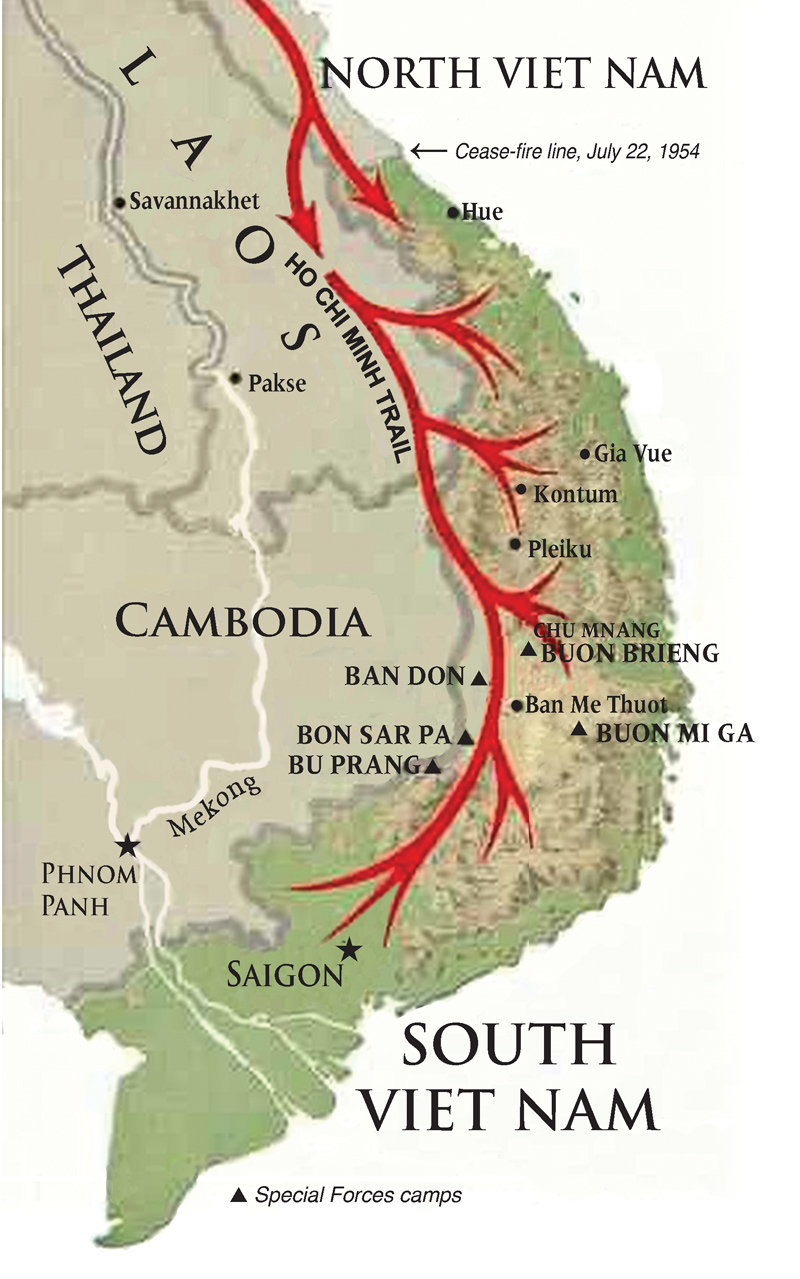

The loose network of trails and roads was named the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The Trail network continued southward from North Vietnam along the Laotian border and eventually through Cambodia with branches of infiltration and supply routes into I Corps, II Corps, and III Corps Tactical Zones (CTZ) of South Vietnam. Overtly, America protected the sanctity of Laotian and Cambodian air and ground space as required by the Second Geneva Accords while secretly carrying out air interdiction missions on the Trail and using Vietnam-based Special Forces reconnaissance teams to locate and monitor enemy activity along the trail. When American conventional units were beginning to encounter large NVA main force units in South Vietnam (1965), locate and monitoring gave way to more intense bombing and other interdiction operations against enemy troops and equipment along the trail.

To protect this logistical network, the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) enhanced the Trail with way stations and storage complexes that were protected by numerous ground and anti-aircraft units. Protecting the Trail required a lot of NVA manpower, as did the maintenance of the Trail from tropical weather and bombing raids. It was thought that if we continuously harassed the Trail with SF-led indigenous recon teams, SF-directed air strikes, and larger-scale interdiction operations, we would tie up numerous NVA forces just to protect the supply lines. This was the origin of the idea of establishing secret US launch areas and base camps in Laos that would provide numerous US-led Laotian guerillas from Laos to harass the NVA further and maybe choke off the supplies needed to carry out the war in South Vietnam.

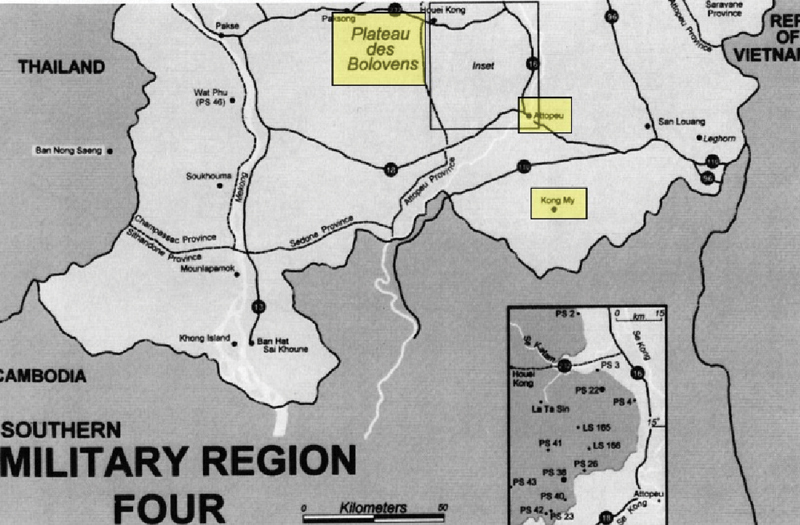

At least that was the mindset as we formed the 46th SFCA at Fort Bragg. It also directed our pre-mission studies to concentrate our B-team’s area of interest on the southern portion of Laos, east of Pakse on the Plateau des Bolovens, a plateau that overlooked the general path of the Ho Chi Minh Trail from the west. Due east of the Plateau at approximately 50 kilometers straight line distance lay the South Vietnam border and its I Corps and II Corps regions. The Fourth Military Region of Laos and especially the Plateau des Bolovens were peppered with CIA training sites, CIA-led special guerilla unit (SGU) garrisons, and technical listening sites to monitor NVA activities and movements. (See figure 2, below)

We were hopeful that after recruiting and training local indigenous forces, we would be able to conduct our own interdiction operations against the NVA trail activities southward and eastward of our location in Laos. In our minds at Fort Bragg, recruiting the local Brao tribesmen to help us interdict the Trail was to be our raison d’être.

“Eight village chiefs lived within the confines of Kong My, each with his own witch doctor and his own following… From this, 1,500 were organized into a local security network. Eighteen teams were then formed, some for road watch and some for action. All were given call signs of various alcoholic beverages. Nearly all of the training was at Kong My, but the best, a 12-man road-watch team named Gin, was put through airborne training at Phitsanulok.” Case Officer Doug Swanson (former SGM, USSF)

Recruiting and training Brao tribesmen was certainly not a new concept. Active recruiting and training of the Brao Hmong tribesmen was carried out by CIA and SF White Star teams as early as 1961, subsequent to President Kennedy taking office and authorizing the expansion of forces in Vietnam and Laos. Then in 1962, after the Second Geneva Accords, the SF teams were withdrawn, leaving only the CIA operatives (many were retired USSF and US Marine personnel) to train and lead Laotian tribesmen against the NVA and their Pathet Lao allies. The center of friendly Brao recruitment was the village of Kong My, a small village south of Attopeu and the Bolovens Plateau. The majority of the Brao in Laos, however, were in Communist controlled areas, including fifty percent of the Brao who lived in Northeast Cambodia. Sandwiched in between Kong My and the Vietnam border was the NVA’s area of control of the Ho Chi Minh corridor into South Vietnam, an area they defended vigorously and relatively successfully until the war’s end in 1975.

This was the situation in Laos that we were prepared to jump into with both feet. Unfortunately or not, Ambassador William Sullivan, US Ambassador to Laos, December 23, 1964 – March 18, 1969, adamantly enforced the restriction of allowing US combat troops (SF) into Laos in accordance with the 1962 Geneva Accords while turning a blind eye to the more deniable secret armies operating in Laos under the control of the CIA. Ambassador Sullivan was a senior statesman in the State Department and wielded a lot of power, so his restrictions were enforced despite the objections of the Pentagon and the CIA.

So here was the 46th SFCA, sitting in Thailand but unable to deploy into Laos. What is to be done with the 46th Special Forces Company? I’ll answer that question in the next installment, where I will discuss the situation in Thailand prior to our arrival and what eventually we were allowed to do to pacify the State Department, the Pentagon, and the Kingdom of Thailand.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR — SGM John Martin retired from the United States Army Special Forces serving over 28 years in the Special Operations Community. John served three tours in Thailand and two tours in the Republic of Vietnam, Okinawa, Korea, and had extensive host nation training missions in Egypt, Sudan, Jordan, Iraq, and Kuwait. Since his retirement from the 1st SFOD-Delta in 1992, he has worked extensively with the Department of Homeland Security and the National Guard Bureau in Washington, DC in the field of Critical Infrastructure Protection. He has a BA and MA and is an instructor at the Northern Arizona University teaching Critical Reading and Writing in the Honors Program.

I am reading this post today from Thailand. I was part of the 46th SF Company and my first job was Secretary/Custodian of the 46th SF Co. ALOHA EM Club located just outside Camp Pawaii in Lopburi. Later, in my second year, I transferred to the Underwater Operations Committee and was Medical Supervisor under control by SFC Walter Shumate. I served with the 46th during the period of 1967 – 1969 before assignment to the Defense Language School in Monterey, California.

I came back to Thailand and made my home here and have been here since 1967. I had my own Dive Shop for the first 20 years and then worked as Commercial Diver for the next 20 years. I retired at age 81 and still here.