Secret Weapon

Luck Strikes at Lunchtime

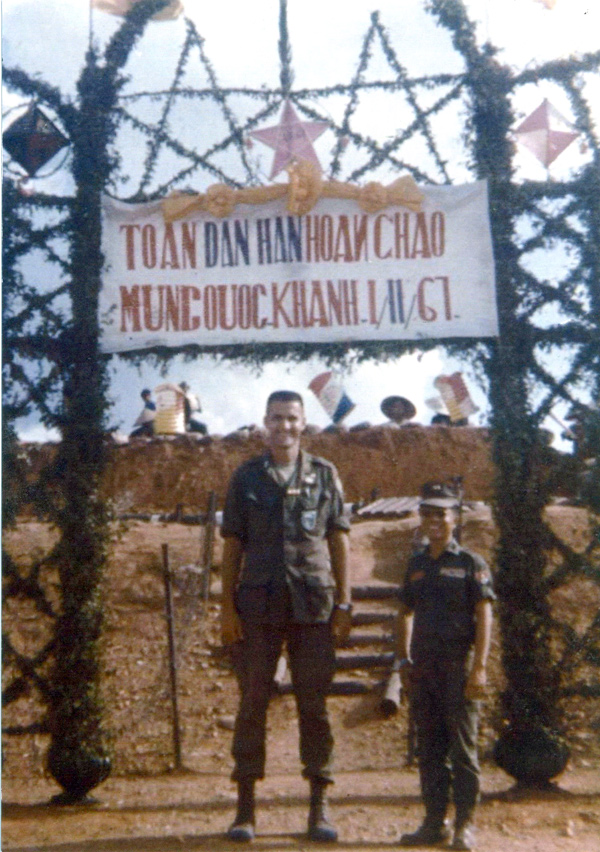

Members of Special Forces A-Detachment 104, 1967. Author appears center front; in the back row, third from the right, Team CO Captain Hugh Shelton, future 4-star General and chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff; the LLDB Sgt. in the back row, second from left, fought at Dien Bien Phu in 1954. (Author collection)

Text and photos by James D. McLeroy

Originally published in Soldier of Fortune Magazine’s March 1988 edition

No matter how much advanced training, technical support and experience you have, in certain life and death situations sometimes the only thing that saves you is plain, dumb luck. Either that or occasionally God decides to protect the unworthy and incompetent for His own mysterious reasons. That’s the only way I can explain what happened to me in Vietnam in 1967.

I was executive officer of Special Forces A-Team A-104 in I Corps, Quang Ngai Province, Ha Thanh District. I was a young, muscular, Airborne, Ranger, Jungle Expert, Green Beret, Infantry first lieutenant, and I considered myself a deadly fellow — all technique, training and esprit. I didn’t need luck I was proud of my special training and my special unit, and I was at least as sincere a believer in our cause (killing the communists) as the communists were believers in their cause (enslaving Southeast Asia).

One night at the beginning of the monsoon season, just before first light, I took one of my typical two-platoon Civilian Irregular Defense Group (CIDG — rhymes with “fridge”) patrols to recon an area for targets of opportunity for ambushes. By chance, around mid-morning of the following day, we happened across a lone VC whom we took prisoner. He was a scared, skinny, teenaged boy who said he had been recruited by force and had just deserted.

Like most Vietnamese and Montagnard peasants, all he really wanted was to go back home to his village and be left alone.

Our CIDG commander threw him to his knees, put a knife to his throat and threatened to cut his head off if he didn’t immediately agree to show us exactly where his supply and infiltration routes were. The CIDG would not have actually cut his throat, at least not with me standing there, but the kid didn’t know that, so he eagerly complied. We then fed and reassured him, for which he appeared to be most grateful.

The area where he proposed to take us was way out on the edge of our normal area of operations, an area where our patrols rarely went because it was so far from the relative safety of our camp. It made sense, though, that if we really wanted to find the VC’s supply routes, we would have to go looking for them in areas where they didn’t expect us to look. I finally managed to persuade the CIDG commander to go. When we got there we carefully set up several area ambushes based on our prisoner’s first-hand information.

On Patrol

Late the next afternoon, from my vantage point in the center of our area-ambushes along the VC infiltration trails, I heard several long bursts of automatic weapons fire — all ours. I soon learned that two of our CIDG units had almost simultaneously ambushed two small VC supply columns. In their enthusiasm to win points for our body count bonuses, which were based solely on confirmed kills, my little CIDG allies proudly presented me with some fresh VC ears. We were, as the saying went in those days, “heavily into” body count. The Special Forces commander in I Corps headquarters had recently flown out to our camp to present us with an actual trophy, sort of like a little bowling trophy, for having achieved more enemy KIAs than any other camp in I Corps for the quarter.

My CIDG interpreter explained that some of the VC supply carriers whom they had just ambushed had had no weapons, which we usually demanded as proof of kills, but the CIDG had wanted to be sure that they got credit for their body count bonuses. Thus the ears. Trying not to appear shocked, I simultaneously congratulated them and gently admonished them from any further ear-taking. I suppose our strategy on that patrol could have been called “winning hearts and minds and ears.”

Hre Montagnard CIDG troops of Ha Thanh SF camp, 1967

The CIDG troops in other camps may have been valiant irregular civilian-soldier patriots, but most of our CIDG were thieving outcasts and draft-dodging, cowardly mercenaries, only marginally better than the Luc-Luong Dac Biet (LLDB), the corrupt Vietnamese special forces that commanded them. Our CIDG mob was about an even match for small groups of the ragtag local VC, but that was not saying much for either side.

Since both the CIDG and the LLDB were our allies, it was considered critical to our mission as “advisers” to maintain at least a superficial facade of what was called in those days “good rapport with our counterparts.” Counterparts or not, the CIDG did not behave like real combat soldiers, and we all knew that it wouldn’t do for us to have to depend on them in any serious hostile confrontation with real soldiers.

Unfortunately, the main force VC companies, led by their NVA advisers, were real soldiers. To know them at close range was usually to regret it. Most especially, as in our case, if you did so with no air or artillery support and a few of the local VC’s ears in your pockets.

Typical Ha Thanh CIDG troops 1967

Lunch Hour

Next day, by unlucky chance, the sacred lunch hour of the CIDG just happened to catch us in an indefensible position. Lunch could really be described as sacred for the CIDG because it was literally more important to them than saving their own lives. As usual, we had to stop dead in our tracks right where we happened to be, precisely at lunchtime, and begin our daily CIDG picnic. I protested in vain.

Although the low jungle growth on the ridge provided us with a modicum of concealment, it gave us virtually no effective cover and no avenues of escape. It was high enough to be conspicuous but not high enough to be defensible, and it was isolated and surrounded by higher ground on several sides. On the other hand, it seemed to be just perfect for gobbling down rice, which was clearly the only point of our being there. Since we were hopelessly stuck there for the ritual noon rice gobbling, I decided to make a routine radio check with our camp.

It alarmed me to hear that our normally calm intelligence NCO was clearly worried. Several of his local intelligence agents had informed him that a main force VC company with NVA advisers, the likes of which we had fortunately never before encountered in our area, was at that very moment aggressively searching for my patrol. He had checked the report with the intelligence section of Special Forces I Corps headquarters in Da Nang for possible corroboration. Their reports independently confirmed the presence of a VC main force company passing through the area of my patrol. Headquarters had also recommended we be unusually vigilant and cautious. I took their advice to be an example of profound wisdom.

Local VC leaders had apparently been informed of our two successful ambushes — and the missing VC ears — and they were not pleased. Dead VC with missing ears were demoralizing to the rank and file conscripts of the guerrillas, and therefore had to be very quickly and conspicuously corrected with an appropriate response. It seemed that the local VC had asked a main force company passing through the area on its way to more significant targets near the coast to find and make an example of us. This was considered necessary in order to maintain morale in the lower ranks of the VC’s local soldiers. We had, in effect, started a sort of rural gang war by flagrantly violating one of the most basic unwritten rules of the territory

The excessive zeal of a few of our CIDG, motivated by their desire to collect another body-count bonus, had apparently upset the balance of power which usually allowed both the VC and the LLDB to prey on the helpless villagers in the area. Obviously, I was a new boy who had to be taught a lesson.

Shots Fired

I was suddenly seized with a powerful desire to move my hips off that ridge. We urgently needed to hide, at least until the weather cleared enough to permit air support. Before I could even begin to discuss the possibility of violating the sacred CIDG picnic hour by simply dropping the rice and grabbing the rifles and rucksacks, I heard one of our Browning Automatic Rifles open fire down the little trail that wandered through the middle of the ridge, immediately followed by a burst of AK-47 fire.

James McLeroy on patrol.

I had routinely put out hasty ambushes along both ends of the trail, and as a matter of routine had given the guards my usual instructions not to shoot any point man who might accidentally stumble by. Instead, they were supposed to radio us of the point man’s approach and then either di di back to us or wait for the main body to appear. As usual, the CIDG guards had decided that if they did exactly the opposite of what I told them to do, it would be an act of profound wisdom. They wanted to be sure that the rest of any VC column that happened to be following the unfortunate point man would quickly and prudently run away, which they usually did, thus avoiding an unpleasant firefight for everyone. By shooting or warning the point peons, the CIDG actually tried to keep VC casualties, and thus future VC retaliation, to a bare minimum, while still appearing to do their job for us.

Unfortunately, however, their little trick didn’t work that day. A few minutes after our guard had so cleverly shot off the top of the head of the VC point man, I appeared on the scene. That immediate answering burst of AK fire made me fear that we had fallen into a trap. With every passing second I sensed that we were being surrounded. Anyone who has ever fought the NVA or main force VC on the ground knows how quickly and fearlessly they can maneuver through even the roughest terrain and dense vegetation. I had heard about it, but this was the first time I had experienced it.

Most American infantry units usually did not even try to maneuver effectively after making enemy contact, preferring simply to call in the ever-present artillery or air strikes and let them do the work. This was standard Army practice at the time. Since the NVA and main force VC had none of that kind of fire support, however, they had to be able to move their feet quickly and at the same time use their weapons, which they did as well as anyone could possibly have done in that terrain. Compared to our CIDG, they looked 10 feet tall — and there were twice as many of them.

Sure enough, we soon began to receive heavy bursts of probing AK-47 fire, first from one side, then another, and yet another. The amazing thing to me was how effectively they were surrounding us in that heavy vegetation. I heard the screams of some CIDG being hit. The CIDG usually manifested one of only two possible demeanors on patrol: lethargy or panic. I knew that we were entering a period of very rapid transition from the former to the latter. I saw the man standing right next to me jerk and turn pale as the stock of his carbine was shattered in his hands by AK rounds. We stared at each other mutely for a few shocked seconds, while he half-smiled at me like an idiot. Maintaining our precious rapport even under fire, I idiotically half-smiled back at him. Just then I felt the whistling of AK rounds ripping over and next to my head, then bits of leaves and branches cut by the bursts fluttered down into my face.

Radio For Support

I thought about all this for one more nanosecond and then hit the ground in a hyperventilating heap, my PRC-25 radio handset pressed to my head, frantically yelling back to the camp our adjusted situation report. The camp informed me that there was, unfortunately, simply nothing that they could do for us. Because of the rainy, overcast weather, any kind of air support was out of the question, and we had no artillery anywhere near. In desperation, I ordered the team sergeant to fire our big 4.2-inch heavy mortar to support us. His response was something of a shock — not only negative, but almost insubordinate.

Author preparing to leave on night patrol.

“Sir, we can’t do that! You’re at max range for the four-deuce!”

“So what,” I screamed back. “Just fire the damn thing anywhere you can about 100 meters around my position!” I quickly spelled out my map coordinates for him, using our standard reference-point code.

“No, sir, you don’t understand,” came back the strained, urgent voice of my NCO through the squelch. “We can’t support you at your range, no way! At max range, we’ve got a margin of error of at least a hundred yards.”

That was true, but not the worst of it. We didn’t even have a real aiming device for the mortar, just some marks on the wall of the mortar pit. It might just as easily kill us as them. In fact, it had never been fired in direct support of a patrol, only for camp defense and occasional harassment and interdiction fire.

“Fire it!” I yelled again. I was, after all, an officer (although a rather junior version of one), and he was an NCO, so I finally ordered him to just fire the mortar in our direction-period. Reluctantly, he decided to “read my transmission.”

When the four-deuce was finally ready, he radioed back: ‘’ For God’s sake, sir, y’all get your heads down now, ya hear, ‘cause here it comes, and God knows where it’s gonna land!”

‘’Fire the son of a bitch and we’ll take our chances!” I roared again. I decided I’d rather be killed by the mortar than be killed or captured by those bastards, which was exactly what was going to happen in a minute if we couldn’t distract them long enough to break contact.

Go ahead — fire it,” I repeated.

So ahead he went — max charge, max range, Hail Mary, devil take the hindmost, Katy bar the door! Meanwhile, AK-47 fire was steadily intensifying from all sides, as was the shouting and screaming of my now almost hysterical CIDG, who had finally realized that they were hopelessly trapped on their cozy little lunchtime picnic ridge. The M30 4.2-inch mortar tube, although rifled, causes a mortar shell fired at maximum range, unlike an artillery shell, to drop almost like a large falling rock, making very little sound as it falls. The shell for the Army’s largest mortar weighs more than 27 pounds and is packed with enough high explosive to virtually pulverize any human being above ground in an area of 40-by-20 meters around the point of impact. The tremendous concussion and shrapnel can also spoil someone’s day considerably farther away than that. At better than 5,000 meters from camp and behind several intervening jungle mountain spurs, we could not hear any sound of firing when it left the tube.

As the VC scout squads around us were probing closer and closer with their fire, and the main body of the company was apparently getting ready for a coordinated assault, the huge mortar round from our camp completed its long journey and landed. Without any warning whatsoever, it suddenly exploded in the low jungle growth about 100 meters below our position, just as requested, with a crashing roar.

The frantic voice of my NCO back in the camp came through the radio static. “Sir, are y’all still there? Over.”

“Outstanding!” I yelled. “Fire it again!”

“We can’t take another chance like that, sir! There’s just no telling where the next one might land! Can’t y’all break out of there?” He was, in effect, being forced to play Russian roulette with our lives, and he really didn’t want to play anymore. I understood, but I didn’t care.

“To hell with it!” I screamed. “Just fire that son of a bitch. I don’t care where it lands!” I was not exaggerating, and he knew it.

His voice sounded agonized and distinctly mournful. “OK, sir, but y’all get way down now, ya hear?’’

We were already as flat on the ground as we could physically be, of course. I knew it would take him longer to get the next shot off because of the intense consultations that were going on down in the mortar pit regarding the critical matter of aiming. We had practically stopped firing back by then because we could not actually see the main body of the VC through the dense foliage, and we knew we were going to need all our ammunition very soon when we would see them. There were moans and cries from the wounded and terrified CIDG.

We knew that those maneuvering VC squads who were effectively reconning us by fire from all sides were trying to get us to return fire blindly so they could locate our key weapons positions. Then they would concentrate their mortar and machine-gun fire on those positions prior to the assault. Their 82mm mortars alone could tear us to pieces, and I suspected they were getting them ready at that very moment. I clung desperately to the radio, trying to derive some reassurance from its continued friendly static, and waited hopefully for our next big mortar shot.

I knew that virtually no amount of casualties would stop a fanatical main force, NVA-led VC company in the middle of an attack. I also realized that I was surrounded by mostly cowardly and incompetent irregulars who were themselves surrounded by a superior number of well-armed, battle-tested enemy soldiers. For the first time since I had arrived in Vietnam, I knew what real fear felt like.

The Aftermath

Suddenly, I saw the excited face of my interpreter trying to tell me something: The enemy’s firing probes seemed to have recently stopped in one of the sectors of our perimeter, and our Montagnard scouts had found no sign of the VC there. The CIDG commander thought that, for whatever reason, the VC might possibly have left us a temporary escape route, and he wanted us to try to break out as quickly and stealthily as possible through that opening. I also noticed that the VC firing had apparently started to diminish, but I strongly suspected that it was a trap to try to channel us into a killing zone. The VC company was so superior to our own CIDG, however, in both quantity and quality, that I figured it simply didn’t matter anymore.

I knew, just as the VC knew, that if we tried to retreat our CIDG would simply panic and run rather than staying together and fighting an orderly withdrawal. I also knew that we would never be able to form any effective defensive perimeter once we got strung out in that thick vegetation. We would either get separated or else all get bunched up together. Either way, we would lose what little semblance of a military unit we had, and most of us would soon be slaughtered. On the other hand, if we remained where we were, their mortars would probably kill us before dark anyway. In the dense scrub jungle below the ridge, we might possibly have some chance of escape. The CIDG could really move very silently when they were scared enough to be properly motivated, and we were all extremely motivated at that moment.

I quickly radioed back to camp for them to hold up on the second mortar shot because we were going to try to move out. We grabbed our gear and our wounded, both walking and stretcher cases, and with uncharacteristic discipline and stealth began to silently make our way through the dripping foliage down that hill, not far from the area where I thought the big mortar round had landed. Somehow, we managed to creep right through the mysteriously convenient opening in the VC lines without ever seeing a sign of anyone or having a single shot fired directly at us. Nor did we ever hear the expected mortar barrage behind us up on the ridge. I kept waiting for the sound of pursuit or ambush or mortars or heavy machine guns, but the VC’s firing had by then virtually stopped on all sides, and we were simply sneaking away from what had appeared only a few minutes before to be a certain death trap.

Several tense hours later we found ourselves out of serious danger and routinely headed back to camp. I kept trying to figure out what had actually happened, but I couldn’t. Somehow, it just didn’t seem possible. We already knew the identity of that VC company, its components, its tactics, and its specific objective from various intelligence reports. Even if we hadn’t known, I thought as I walked along in a daze, they had already given us their unmistakable signature by means of their fast, coordinated reconnaissance of our positions by AK-47 fire and their typically efficient encirclement of our perimeter so soon after we had shot their point man.

Our local VC irregulars simply never, ever did that. They didn’t have the necessary leadership, training, weapons or confidence to do it. Their only combat responsibility was to snipe, ambush, mine and then break contact so they could do it all again another day.

Yet, when they obviously had us surrounded and outnumbered, with no air support possible, it was almost as if some unseen “movie director” had suddenly ordered the main force VC “actors” to simply move off the set so that we could shoot the next scene, which was to be entitled: “CIDG limping safely back to camp with their wounded.” Just like that? We had been as good as dead meat up there and the VC knew it, yet here we were. I kept turning it over and over in my mind, but it still didn’t make any sense.

The cumulative tension and stress were finally getting to be too much for me. Although I didn’t realize it at first because my voice was still relatively calm, I was literally shaking inside with built-up tension and fear when we finally got back to camp. Even the customary shower and double shot of bourbon couldn’t calm me down that night or the next day.

The Secret Weapon

Finally, by chance, our intelligence NCO came upon the explanation for what had occurred. Late in the afternoon of the day following our return, he received a report from one of his chief agents, a prominent Vietnamese civilian in the nearby village. This man had no specific knowledge of our patrol or of the little drama of the mortar back in camp. He reported that the latest “hot word” in local VC circles was that a terrible disaster had befallen a main force VC company passing through our Tactical Area of Responsibility the previous day. Moreover, this completely unexpected and unexplained disaster had seriously demoralized all the local VC supporters and sympathizers there because of it’s peculiarly ominous circumstances.

The ”word,” as he reported in the meeting with our intelligence NCO, was that a main force VC company had been in the process of attacking an outnumbered CIDG patrol which they had trapped a long way from any camp’s normal area of operations. The VC company commander, his NVA advisors and most of his headquarters’ staff and platoon leaders had been assembled around the VC company commander to receive their instructions for the assault when they had somehow just suddenly been wiped out — simply disintegrated — in one huge explosion, right out of nowhere.

Seventeen of the key people in the company had just miraculously blown up, without any warning, in one explosion out in the jungle, with no airplanes or helicopters anywhere near the place. This sudden disaster had been so confusing and demoralizing to the remaining VC soldiers that they had been forced to disengage immediately and disperse as quickly as possible.

What had all the other VC in the area so worried now was their conclusion that the Americans had apparently introduced some new weapon, something like a small, tactical version of the dreaded “arc-light” (B-52) bombings. This conclusion seemed inescapable in view of the fact that the VC had never seen, or even heard of, anything remotely comparable to that much concentrated and accurate firepower coming from any type of conventional weapons carried by any CIDG patrol before.

Their conclusion, therefore, was that the unfortunate main force of VC company had probably been suckered into surrounding that particular CIDG patrol so that the American Special Forces advisors with the CIDG could have an opportunity to use their new secret weapon to annihilate the infrastructure of one of the VC’s better units. The implications of this weapon for the local VC’s combat future were clearly awesome.

This agent had uncharacteristically decided to risk his own cover security in order to personally inform intelligence NCO that, whatever our new secret weapon was, it was working unbelievably well and that we should, by all means, keep up the good work. The first tremendous hit already had the local VC staggered, he urged, and just one more number like that would put them right on the ropes.

Our intelligence NCO managed to appear appropriately grave and noncommittal until he could get back to camp to share the story with me. When we both finished laughing, I finally started to relax a little.

I only hope I never again have to be quite that lucky. “Secret weapons” as good a that one are damned hard to come by.

Author standing on the base of the flag pole at the ruins of the Kham Duc SF camp in 1998, 30 years after the Battle of Kham Duc in 1968.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR — James D. McLeroy completed Infantry, Airborne, Jumpmaster, Ranger, Special Forces and Jungle Warfare training. He served an extended combat tour in 1967-68 as a Special Forces first lieutenant in both 5th Special Forces Group in I Corps and in MACV-SOG.

He co-authored BAIT: The Battle of Kham Duc, which was reviewed by Kenn Miller in the March 2019 Sentinel. BAIT has been published in paperback and recorded as an audiobook available on Amazon.

McLeroy was interviewed as part of the Veterans History Project. Listen to his personal narrative on the Library of Congress website https://www.loc.gov/item/afc2001001.113566/?

I was at Ha Thanh with the I Corps Mike Force in Feb 1967 and fought several engagements at OP69 a few miles north east of the camp. I’ll send that story to James if he’d like like it. Lt Heaukalani was XO in the camp then.