SAIGON MEMORIES — 1990

Saigon's Chinese quarter, Cho Lon 1990. (Photo by Marc Yablonka)

By Marc Yablonka

Beatle John Lennon once declared New York City the “Center of the Universe.” But as I swung open the doors to the lobby of the Continental Hotel in downtown Saigon in 1990 and walked out onto Lam Son Square, I formed a very different opinion.

All at once, Bui Doi, “The Dust of Life,” mixed children of American GIs who had been forced to desert Vietnam, accosted me with shouts of, “Ba! Ba! Ba! Ba! (Father! Father! Father! Father!), give me `monay!’ Give me `monay!’” I was barraged both aurally and physically.

Along came Mr. Manh, a local “xich lo” driver, who saved me from the onslaught of teens. Some fair-skinned, some dark-skinned who possessed the typical features of their Black fathers. Manh and I adopted one another that rainy morning, and he was to fend for me and cart me around the entire time I was in Saigon. Once even chasing away a would-be thief who was eyeing my camera as he rode by.

Yet, Manh would constantly refuse my attempts at remunerating him for the destinations he would take me to throughout the city, waiting diligently for my return. It was as if he knew, and rightfully so, that there would be an American pot of gold awaiting him the night before I would depart Saigon. I handed him that pot of gold on my last night. The sum of US $20. At that time enough to feed his family rice for a month, so I was later told.

As my Thai Air flight made its final approach into the former Tan Son Nhut Airbase that had been so crucial to the American war effort, including the American departure from Vietnam in April 1975, through the fog I could make out the revetments that had sheltered American bombers from attack by the Viet Cong. They were still there in 1990. Yet empty of war planes.

Instead, Russian and East German made Tupolev 134s and smaller Ilyushin short haul jets lined the runway. All bearing the livery of Vietnam Airlines. All purportedly in various stages of airworthiness and disrepair because of a shortage of replacement parts, said some, because of the American embargo still then in place on Vietnam. Others opined it was because of unscrupulous Russian parts dealers. Whatever one believed, the planes, manufactured by Russian carrier Aeroflot and East German manufacturer Aeroflug, were crashing in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia all too frequently in the 1980s and 90s.

Before wheels down, a Band of returning Australian Brothers had jumped up to peer out of windows at the airport they had most likely left 25 years earlier.

An abandoned Huey by the side of the road (Photo by Marc Yablonka)

Once off my Thai Air flight and in the customs line, I made conversation with a San Diego-based attorney who’d come with his adopted Vietnamese daughter because, then a high school senior, she wanted to see where she had originally come from. As it turned out, we were all staying at the fabled Continental Hotel. And, as it also turned out, I was able to be of some assistance to him and his daughter in determining the orphanage which cared for her until she was adopted.

Soon, I was safely ensconced in my room at the Continental, where so many news bureaus had offices during the Vietnam War, and which Graham Greene had featured in perhaps his most famous novel, anti-America slanted The Quiet American. For many years, anyone declaring himself or herself a journalist upon checking in at the Continental received a 40% reduction in charges. Suddenly, I was jarred out of a reverie by the ringing phone by my side.

“Hey Marc,” my new attorney friend said. “They’ve got a massage parlor on the second floor!” My response as a happily married man at the time, was tepid at best. I was later to learn that massage parlor was legit. Not at all like the massage parlors out behind joints frequented by American GIs like the “Hollywood Bar” or the “New York Bar” during the war. And I admit it. I imbibed…once. Even got my back walked on by a tiny Vietnamese girl who told me, “I only 19!” My reply: “I only 40, and I married!”

Continental Hotel, Saigon (Photo by Marc Yablonka)

Orphanage #1 (Photo by Marc Yablonka)

A couple of months prior to touching down in Saigon, I had occasion to be watching Larry King on CNN. He was interviewing Cherie Clark, one of the founders of Friends of Children of Vietnam, a group dedicated to placing Vietnamese orphans in American homes. But Cherie was not new to that line of work. She’d done the same thing as Saigon was falling to Communist forces in April 1975, lending a hand to “Operation Baby Lift.” And, after a stint assisting Mother Theresa at her dispensary in India, Cherie was back in Vietnam.

I’d been able to contact Cherie through her organization’s Bangkok office prior to my arrival in Saigon and arranged to tag along on one of her missions to secure adoptions. As we drove from orphanage to orphanage, I was completely taken in by these children and nonplussed as to how and why anyone in their right mind would give them up. Apparently, Woody Allen and Mia Farrow, then happily married, felt the same as I did because they accepted one of “Cherie’s kids” into their home. Once I was home, I profiled Cherie for the Jakarta Post newspaper.

Notre Dame Cathedral (Nha Tho Duc Ba), District 1, Saigon (Photo by Marc Yablonka)

There were several other indelible experiences from my time in Saigon. Among them the night my attorney friend and I dined at an outdoor restaurant whose name escapes me so many years later. As we ate, our waiter bent down close to us and whispered, “Please help me. My ODP (Orderly Departure Program) case very slow. This my number.” He handed a slip of paper to the attorney, who promised to look into his case once home. Moments later, we spied the waiter’s boss looking evilly suspicious at him. Obviously, a loyal party member. I pray the man is safe and fulfilled somewhere in these United States.

Another night, in Cho Lon, the Chinese quarter in Saigon, in the home of Mr. La, the uncle of a colleague back home, over a dinner of delicious “Chao Tom” (Shredded shrimp baked on sugar cane), the power in the district suddenly went dead. We were forced to eat Mrs. La’s delicacy, still a favorite, by the purplish light of a mosquito lamp.

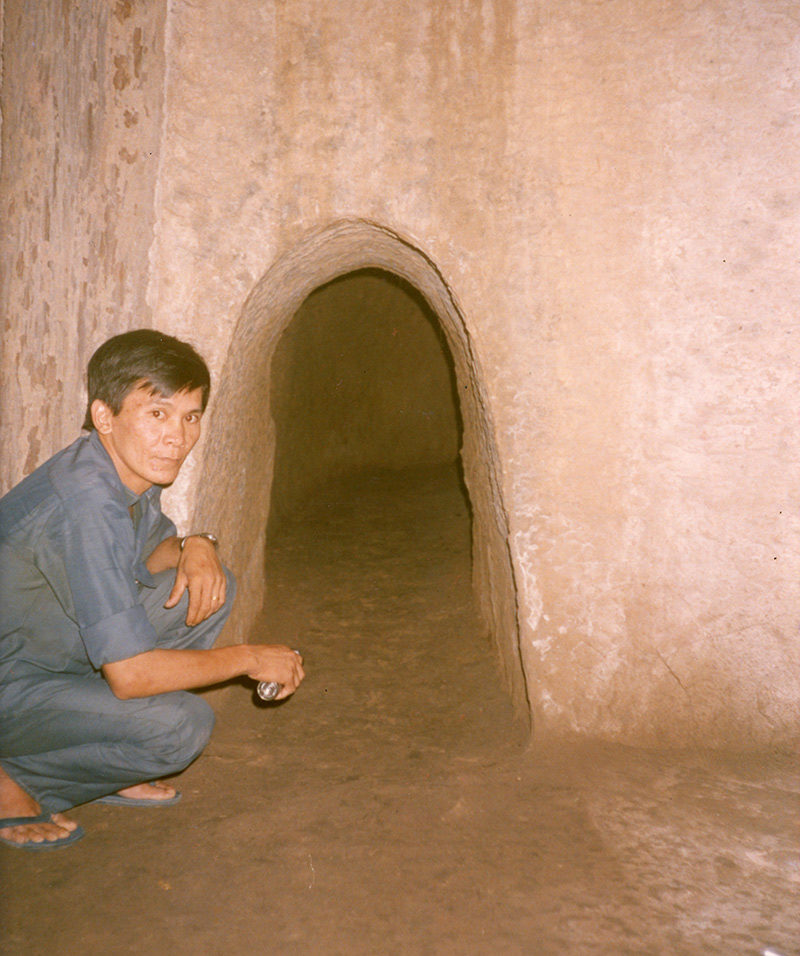

Second level of the Cu Chi tunnels with former VC guide. (Photo by Marc Yablonka)

Perhaps the most memorable of my experiences of that journey took place outside of Saigon at the infamous Cu Chi Tunnels, about 50 kms. outside of the city. As is well-known today, the tunnels housed Viet Cong cadres who often lived submerged during entire days, only to come out at night to fight the American “imperialists.” The tunnels purportedly reach all the way from Saigon to the Cambodian border.

In 1990, the Cu Chi Tunnels weren’t even a blip on tourism’s radar. Today tourists come off the cruise ships from Singapore and are bused to what has become a nauseating attempt at drudging up war propaganda for the almighty US dollar. Why…tourists even get to shoot AK-47s for one of those USD! The tunnels have purportedly even been bored out to accommodate western torsos.

When I arrived there, the Cu Chi Tunnels amounted to a hooch in the middle of nowhere with a handful of former Viet Cong, one minus an arm he claimed had been shot off by an American GI for whom he no longer bore malice. One of the VC offered to take me down into the tunnels. I obliged him with trepidation. We went down two levels, which afforded me the chance to see a kitchen, a schoolroom, and a makeshift hospital. He offered to take me down another level, but an odd-looking insect made up my mind for me. I elected to return to the surface. Before departing, I noticed a beat-up old armoire in the hooch upon which some visiting US Marines who had preceded me had stuck one of those iridescent USMC automobile stickers. I thought to myself, “How ironic is that?”

At left in the above photo, Marc Yablonka's article about the Continental Hotel for the Pacific Stars and Stripes framed and displayed in its lobby (Photo courtesy James Caccavo)

I left Vietnam on its notorious national carrier, Vietnam Airlines. An airline I would have no trouble boarding today. But at the time, survivors of its flights had taken to twisting its Vietnamese name “Hang Khong Vietnam” to “Hang On Vietnam” or “Air Nuoc Mam,” a reference to the pungent fish sauce that Vietnamese are known to use in many of their dishes.

Thank God, my flight made it to Bangkok without incident. But as I looked around prior to take off and saw that the seat in front of mine was not properly bolted to the fuselage floor, the seatbelt in the seat next to mine wasn’t working properly for its passenger, and the flight crew could do nothing about it, I wondered if we would make it. I would return to Saigon five years later. To my old haunt, the Continental Hotel, which I wrote about for the Stars and Stripes. And to a much more prosperous “Pearl of the Orient.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR — Marc Yablonka is a military journalist whose reportage has appeared in the U.S. Military’s Stars and Stripes, Army Times, Air Force Times, American Veteran, Vietnam magazine, Airways, Military Heritage, Soldier of Fortune and many other publications.

Between 2001 and 2008, Marc served as a Public Affairs Officer, CWO-2, with the 40th Infantry Division Support Brigade and Installation Support Group, California State Military Reserve, Joint Forces Training Base, Los Alamitos, California. During that time, he wrote articles and took photographs in support of Soldiers who were mobilizing for and demobilizing from Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom.

His work was published in Soldiers, official magazine of the United States Army, Grizzly, magazine of the California National Guard, the Blade, magazine of the 63rd Regional Readiness Command-U.S. Army Reserves, Hawaii Army Weekly, and Army Magazine, magazine of the Association of the U.S. Army.

Marc’s decorations include the California National Guard Medal of Merit, California National Guard Service Ribbon, and California National Guard Commendation Medal w/Oak Leaf. He also served two tours of duty with the Sar El Unit of the Israeli Defense Forces and holds the Master’s of Professional Writing degree earned from the University of Southern California.

cuando menos está lectura me permitió comprender una película de Netflix, FURIES, sobre la delincuencia en Saigón en 1990

Gracias por sus amables palabras, señor. Sospecho que el crimen en el Tercer Mundo continuará para siempre. ¡Desafortunadamente!

Could you please help me get ahold of Cheri Clark. I am an adoptive mother of 2 Vietnamese children and am taking them and their children to Viet Nam to show them where their parents came from. I took my children there in 2004 and met up with Cheri by a stroke of luck. I would like to meet up again if she is still there. We are going in March 2025. Thank you for your help.