Paying For It With Our Sanity

By Alex Quade, War Reporter, Honorary SFA National Lifetime Member

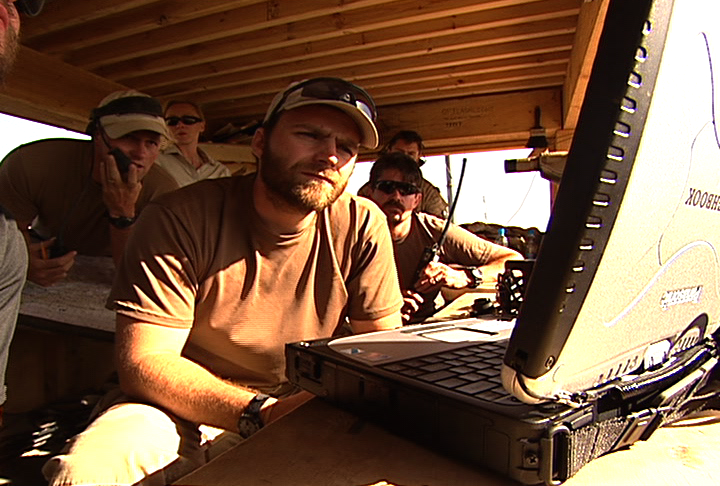

Rare photo of Greg Danilenko smiling. Iraq, June 2007 (Courtesy Alex Quade)

“After so many years and so many wars, the dead and I have come to a certain understanding. If our paths should ever cross, they were to lie still, and I would, in return, give them as much dignity in their tragedy with my pictures as my skills permitted. There are things I wish I were not good at. This is one of them. I feel no joy or pride in that. It is a service that I provide as a member of mankind, paying for it with my sanity.

The world is not always pretty. Some choose to ignore it in fear of seeing the truth and confronting it. And there are those who accept such a cruel reality and do the best they can, if not to change it, then to at least record it for the chronicles of time, for future generations, in the hope that those who will come after us, will look at what we did to one another, and say — ’We will not repeat the sins of our Fathers. We will be different.’ It is only a hope. But without faith in humanity and hope for a better world, what else is there to live for?”

THAT… was the letter my late cameraman sent me after our last combat mission together – that “Chinook shootdown op”.

Greg Danilenko passed away suddenly, a few years ago. He was my CNN teammate, before I became a one-man-band to continue covering Special Forces.

For me, Greg’s shooting was visual poetry.

I’d asked to work with him, specifically (after refusing to work with my former cameraman, whom I could no longer trust – you cannot operate in hostile environments with people who don’t have your back – but that’s another story).

Greg was difficult – but so am I.

The first time we worked together, we “clicked” professionally. His footage was a joy to edit. Not a frame he shot was wasted energy.

He told me, he came out of “self-imposed war zone retirement”, just to work with me — because I was known as “A Photographer’s Producer” – who would make his pictures sing. I didn’t figure out why he’d imposed this hiatus, until later.

Greg said he was up for the mission. In hindsight, I wonder if he knew it would be his “last hurrah.” I knew I could count on him to get great “bang-bang”, because he’d covered the Chechen conflict — which had bothered him. I don’t know if he ever shared that with anyone other than me — he would cry about “All the dead boys” he’d shot footage of long ago, when he drank vodka.

I thought — because he was as “hard core” as I was, with work and war zones under our belts — that I wouldn’t need to worry about him. He said he could handle it — but I’ve always wondered if I pushed him too far — with that long, last mission with the troops in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Greg was a serious Russian and rarely showed emotion — so the relief on his face when I landed after an F-16 ride-along doing aerobatic maneuvers — was a big surprise.

Alex Quade finishes F16 flight — pulled 9.3 Gs! (Photographer, Greg Danilenko, courtesy Alex Quade)

“I thought you were going to die,” he said. I was grinning ear-to-ear; he was horrified.

He glared at me — after I dangled from a helicopter with the PJs, then he shot amazing, “you-are-there” footage as we bounded with them in the dark. Even in the action, he “edited in the camera”, finding angles and details.

Alex Quade finishes F16 flight — pulled 9.3 Gs! (Photographer, Greg Danilenko, courtesy Alex Quade)

Greg had an “eye” — and a signature, artistic shot — always of a sunset or the sun behind some piece hardware. That’s where he found beauty.

We “GOT” each other — though he was not enamored with my plans to fly AF cargo hip-hop (instead of commercial business class with drinks). I figured, if it’s good enough for the troops, it’s good enough for we who cover the troops.

Waiting for sunset to launch fatal air assault, KAF, May 30, 2007. CH-47 ‘Flipper’ unit on tarmac. (Photographer Greg Danilenko, courtesy Alex Quade)

He was “less than pleased” — when we bunked in for a week with Canadian SOF at Kandahar Airfield (KAF), with the CCTs and STS guys we were with, as we waited to push out to Sper Wan Gar and Lash Kar Gar. The Canadians liked to walk around wearing nothing but a towel, singing in French — “Bonjour, Mademoiselle…” (Think towels were added merely because this lone female was now temporarily living with them.)

Greg was stubborn and irritable — refusing to shoot moments I’d enthusiastically point out in the field with the troops that I thought captured humanity in the situation we were in — “Alex, I didn’t come to Afghanistan to shoot video of soldiers playing with goats and chickens.” So, I did it myself. He wasn’t very excited about the camel spider they’d captured and turned into a pet-in-a-metal-bucket, either.

‘Pet’ camel spider. Embedded with SOF at Observation Post near Lash kar Gar, Afghanistan, Apr 2007. (Courtesy Alex Quade)

Alex Queade embedded with CCTs and STS, watching CAS over battle in valley below Sper Wan Gar OP, Apr 2007, Afghanistan. (Photographer Greg Danilenko, courtesy Alex Quade)

I exasperated him. My work ethic was what impressed him — “I’ve never seen any reporter get this access with the military ever,” and

“I know I can trust you to do justice to my footage,” — were the nicest things he ever said to me.

He refused to talk to me after that combat operation that was too close for comfort.

“His eyes were wide as saucers, when I told him a Chinook got shot down,” our JTAC Jimbo told me later. I’d separated us on that air assault — figuring if we’re each shooting footage, we’re covering more ground. He was in a Blackhawk with Command; I was in another Chinook with the Joes.

Danilenko snapped this photo of Alex Quade using her IBA as pillow for powernap in 125-degrees, between CAV & 10SFG ops, Baqubah, Iraq, June 2007. Because, he said, she was “a workaholic who rarely slept.” (Photographer Greg Danilenko, courtesy Alex Quade)

Heading to CH-47 aircraft for air assault May 30, 2007, into Sangin River Valley, Helmand Province, Afghanistan. (Photographer, Greg Danilenko, courtesy Alex Quade)

I failed him.

Perhaps I should’ve sent him home as soon as we landed back at Kandahar Airfield after that Chinook shootdown mission. But, he’d decided to speak to me again, and said he was good to head to Iraq; and after the “3-Beers-Allowed” policy at Al Udeid Air Base, Qatar, he seemed better.

Fought a word battle in my head – “I can’t push people as hard as I push myself.” (Maybe that’s why Ranger Bob Howard and I related to each other so well. Bob also told me he “Can’t stand hurt feelings, whining and complaining” — but that’s another story.)

Air Assault into Helmand Province, from KAF, May 30, 2007. (Courtesy Alex Quade)

With CCTs and Canadian SOF calling in CAS for battle in valley below Sper Wan Gar OP, Helmand Province, April 2007. (Courtesy Alex Quade)

Made a hard decision. Mission-Men-Me.

…To continue the mission…

…To take care of my battle buddy…

…To go it alone.

So, I sent him home early from Iraq. I lied to him. Said there was only room for me on the next embed with 1SFG’s CIF, Commanders In-extremis Force, doing ops in notorious areas of Baghdad, such as al-Shula and Sadr City.

TIC. Embedded with troops, Helmand Province, June 2007. (Courtesy Alex Quade)

Above, Day 2 of Chinook Down Op. Leaving compound for overnight town clearing ops, Kajaki Sofia area of Helmand Province, Afghanistan (Photographer, Greg Danilenko, courtesy Alex Quade)

When I finally came “home” (translation: re-supply between 10SFG ops in Diyala Province near the Iranian border), I secretly talked with Greg’s boss — to make sure he was ok, to explain what happened on the “that Chinook shootdown mission,” that it may have affected him, that he might need help.

“He hasn’t been the same since he got back,” his boss confided.

I felt guilty.

I had Greg’s back, though he never knew it. He only knew I was the workaholic who sent him home. But, I still felt like I’d figuratively left a battle buddy behind to deal with his trauma, so I could continue the mission of covering SFODAs without him.

Greg and I didn’t talk for a long time after our last mission. He was “feeding the beast”, doing day-in/day-out coverage in New York for “the mother ship” (CNN). I was busy running around by myself downrange covering Special Forces teams.

Then, he sent me this letter.

And another.

And another.

And another.

A trove of impressions from our frontline experiences, focusing on the work we do in hostile environments:

“…It is a service that I provide as a member of mankind, paying for it with my sanity. The world is not always pretty. Some choose to ignore it in fear of seeing the truth and confronting it. And there are those who accept such a cruel reality and do the best they can, if not to change it, then to at least record it for the chronicles of time, for future generations…”

Greg never went back to war again. He was fighting his own battle — just like many of the soldiers we’d covered.

Though I’ve been a one-man-band for nearly 15-years — I miss having a teammate. Having a cameraman was a privilege. Working with someone so talented was also a privilege. I learned a lot from Greg.

Right before he left this earth, Greg reached out asking to work together again in Syria and other war zones. He’d left CNN. His second marriage ended in divorce after coming home from “that Chinook shootdown op.” His third marriage was crumbling.

“One other thing you must grasp… my son graduated from West Point this spring, that was no accident. My daughter Becky is grown up. You know the ODA rotation. My sense of smell tells me you need a person on the ground,” he wrote.

Danilenko’s son, Thomas, graduates USMA, West Point. From left to right, Mom Paula Garb, daughter Becky, son Thomas, Greg, Greg’s 3rd wife. (Courtesy Alex Quade)

I don’t know if he was turning over a new leaf — or seeking that old “fix” — that comfortable and reliable standby for so many of us — running away back to war, where everything seems clearer. I just knew I couldn’t take him with me. His emails became more fervent.

“You’re not listening. I’ll find gear. You gotta work with me… God, you are so stubborn!”

But my gut told me he was “non-deployable.” He’d be a potential liability to the teams when they were already stuck with me. Greg kept emailing, despite my declines.

“You need to start trusting people in your life… yeah, I’m still an asshole. If I can’t find gear, I’ll still go… if for no other reason than to get objective feedback from that area for your print or social media. At this point, I do not have an expiration date for this trip,” he pleaded.

“Stand down,” I told him. “Ok,” he replied.

Within a month, Greg Danilenko was dead.

Another casualty of “that Chinook shootdown op.” Another casualty of war. Another statistic.

I didn’t share his writings, out of privacy and respect, until his mother Paula Garb reached out to me later. Greg’s son Thomas had already served in Afghanistan, daughter Becky was married. She gave me permission to share Greg’s writings — that it might help others.

“After the divorce, which coincided with the worsening PTSD symptoms, Greg started to go off the rails with his drinking. He was ashamed to admit to anyone how he was dealing with the pain. The trauma became so deep he couldn’t manage it,” Greg’s mother wrote.

“I think, too, that journalists just don’t have the kind of support systems that the military provides these days. It’s hard enough for soldiers to get treatment, but the journalists are completely on their own,” she added.

Greg Danilenko is now at peace.

He was a great father, son, cameraman, teammate, and friend.

I will always honor him, his work, and his family – as I do the troops I cover in tough situations.

For those of us who run towards danger, it seems obscene to talk about our pain, when we’ve seen what we’ve seen of other people’s pain. We use our job as our best defense.

Combat veterans, first responders and journalists reading this — if you can relate to any of the above — please talk with someone about it. Share your experiences with someone. What you did has value and meaning.

YOU ARE NOT ALONE.

God bless Greg’s family. God bless our Fallen. God bless all those who go into harm’s way.

About the Author:

Alex Quade is an award-winning war reporter and documentary filmmaker who prefers flying under the radar downrange and letting her life’s work speak for itself. Former Commanding General of USASFC, and SOCEUR, MG (ret.) Michael Repass describes Alex’s work this way: “War correspondent Alex Quade is this generation’s Joe Galloway, who tells intensely personal stories. Alex nails the essence of sacrifice found in America’s Special Forces operators and their families. Alex Quade is the real deal. She’s spent more time with Special Forces operators in combat zones and back home after deployments than any other reporter. Alex knows them and their families, and is uniquely qualified to tell their intensely-lived, extraordinary stories.” Hachette is publishing Alex Quade’s book on this operation. For more info: alexquade.com

Photo: Alex and Maggie

Photo: Alex and Joe Galloway

Leave A Comment