PART TWO:

The “Double Nickel” — Special Forces in El Salvador

Editors Note — In the Part One , read it in the September issue of the Sentinel.

By Greg Walker (ret), USA Special Forces

The war that never should have been – Massacre at El Mozote

“Mrs. Amaya said the first column of soldiers arrived in El Mozote on foot about 6:00 p.m. Three times during the next 24 hours, helicopters landed with more soldiers. She said soldiers told the villagers they were from the Atlacatl Battalion. ‘They said they wanted our weapons. But we said we didn’t have any. That made them angry, and they started killing us. Many of the peasants were shot while in their homes, but the soldiers dragged others from their houses and the church and put them in lines, women in one, men in another.’ It was during this confusion that she managed to escape.

“She said about 25 young girls were separated from the other women and taken to the edge of the tiny village and she heard them screaming. When asked why the villagers hadn’t fled, Mrs. Amaya said, ‘We trusted the army.’ From October 1980 to August 1981, there had been a regular contingent of soldiers in El Mozote, often from the National Guard. She said they hadn’t abused the peasants, and that the villagers often fed them.”

“Massacre of Hundreds Reported in Salvadoran Village,”

The New York Times, Raymond Bonner, January 1982

Why Did They Have to Kill the Children?

Maj. Natividad de Jesús Cáceres Cabrera, second in command of the Atlacatl Immediate Reaction Battalion, was frustrated. He’d just ordered the men under his command to begin killing the children of El Mozote. They’d shown little hesitation in the killing of adult and elderly men in the village, and no hesitation at all in leading away the young girls, most between 12-to-15, whom they gang-raped, then butchered.

But the children, the ninos and ninas, they were now a problem. Major Cabrera was a true believer. The only good communist was a dead communist. And one dead communist child was one less future communist guerrilla the Salvadoran Army would have to fight.

El Mozote was a limpieza operation — a “cleaning up” of the communist guerrilla presence and control in the Department of Morazán. The Atlacatl Battalion was newly reformed and devoid of American Special Forces combat advisers. Lt. Col. Domingo Monterrosa, the battalion commander, was going to fight the guerrilla armies of the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN)—one of the two primary political parties in El Salvador—his way.

Atlacatl was to be the Einsatzgruppen. Just like the Nazi “deployment units” raised by Heinrich Himmler — the founder and overall commander of the SS during World War II—the Atlacatl was the mobile killing unit of the Salvadoran High Command. Special tasks included the execution of communist party functionaries, FMLN and Catholic church officials, and FMLN political officers; as well as men, women, and children in those areas the military command deemed under the control of the guerrillas.

“Everything points to the fact that if ‘civilians’ of Catholic and evangelical affiliation died in the battle that took place in the El Mozote hamlet, were they linked to the activities of the terrorist group ERP [People’s Revolutionary Army]? The answer is yes, and this is what the report from the Department of State of the United States of America explained: El Mozote is located about 25 kilometers north of San Francisco Gotera, the capital of the department of Morazán. El Mozote hamlet was in the heart of the zone under constant siege by the ERP insurgents.

“The investigation confirms that the settlers of the El Mozote hamlet were collaborating, voluntarily or involuntarily, with the insurgents. The report also revealed that the insurgents mobilized their supporters within the area of influence in the north of Morazán to harass the military units of the Armed Forces while they were advancing in the area. The insurgent forces had been permanently re-established in the El Mozote village since August 1981.” “Mountains of Morazán: The Muda Verdad of El Mozote,” Charly Monterrosa, http://www.domingomonterrosa.info/2015/02/20/montanas-de-morazan-la-muda-verdad-de-el-mozote/

“We Carried Out a Limpieza There” — Colonel Domingo Monterrosa

Major Cabrera, like his commander, believed in leading from the front. Ordering an infant to be brought to him, he held it in hand while unsheathing his bayonet with the other. Amid a cascade of gunshots, young girls’ screams, and the smoke and stench of tiny homes burning, Cabrera threw the baby skyward, and speared it as the tiny body fell back to earth.

This wanton act of murder was attributed to U.S. Special Forces advisors over the years; a mixture of FMLN wartime propaganda and myth. It would take years to counter this allegation, an echo of North Vietnamese propaganda circulated during that war meant to discredit and diminish the presence and effectiveness of “The Green Berets” as they decimated the NVA and Viet Cong on a daily basis.

“Fog and friction are hard truths of war. Another hard truth is that the inevitable first casualty of war is the truth itself. El Mozote was a tragic consequence of the higher purpose that America was pursuing in El Salvador at the time…” — Dr. Todd Greentree, former political officer, El Salvador.

“Saigon had fallen just a few years earlier, but after Nicaragua, the US was not going to lose another country to the Soviet Union and Cuba in Central America. President Carter found aiding the Salvadoran government extremely distasteful, and his ambassador, Robert White, was an emotional human rights crusader, especially after the four churchwomen were raped and murdered on his watch. Yet, it was Carter who authorized lethal assistance to the Salvadoran military in one of his last decisions before leaving office in January 1981.

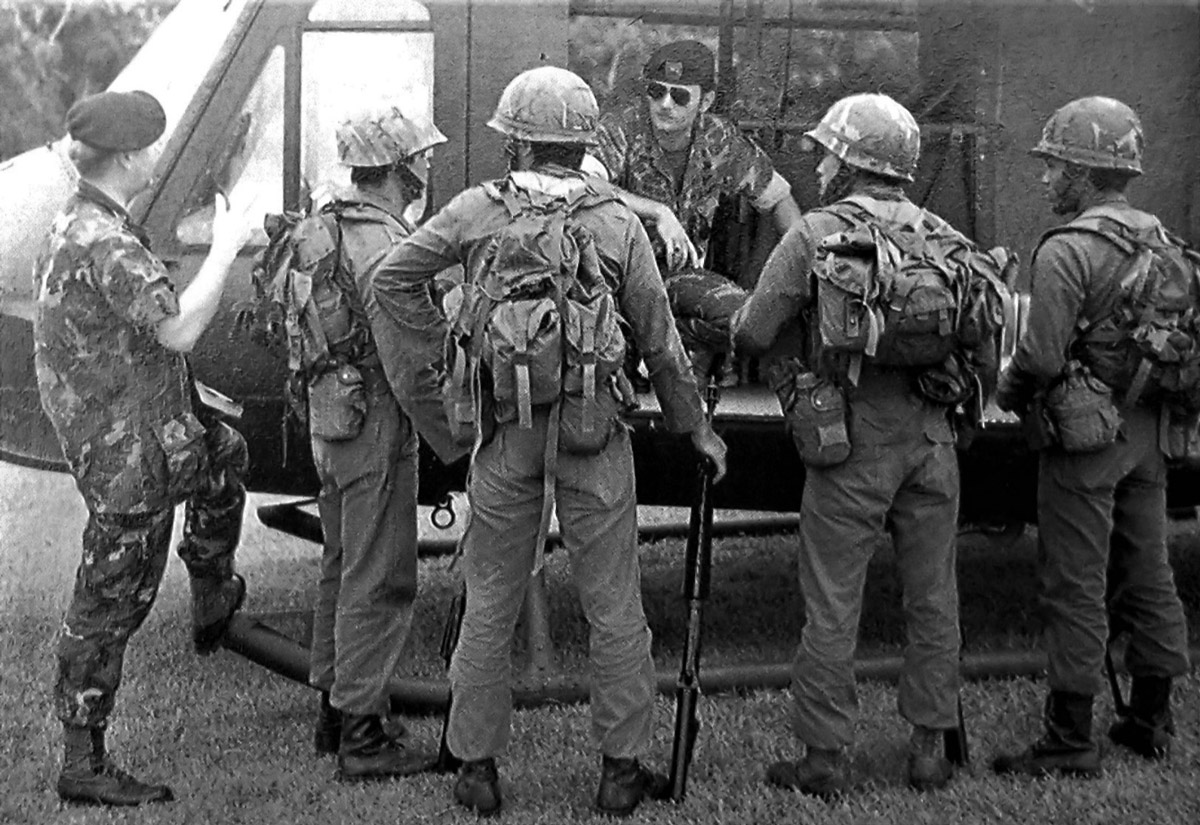

(Photo courtesy the Greg Walker Collection)

“Reagan inherited El Salvador as his first foreign policy crisis. He eventually embraced counter insurgency but was initially more concerned to reassure Americans that El Salvador was not going to become another Vietnam. This was the source of the agreement with Congress to limit military trainers to 55 and to prohibit combat advisors from the field. As the first US trained and armed, equipped RRB, Atlacatl was under a microscope. Worse, shortly after they went out on their first big operation and committed El Mozote, Reagan was due to certify to Congress that the ESAF was taking measures to improve human rights. If the [U.S.] Embassy had unequivocally verified the massacre and US officials had testified that the [Salvadoran] military was responsible, Congress would have had to cut aid, even though they knew perfectly well it would have meant game over.” — Dr. Todd Greentree, letter to the author, May 26, 2021

Politically the war in El Salvador was never about democracy, or nation-building, or human rights. Despite public claims otherwise the Reagan Administration wanted, indeed was demanding, a full military victory over the communist insurgents. This while at the same time using El Salvador as a staging area for supporting what would become known as the Contra War in Nicaragua. For Special Forces in specific the politics were neither here nor there. Our job was to take the fight to the FMLN guerrillas and either bring them to the bargaining table in the understanding they would never win a military victory or dismantle their war-making machine to the degree the Salvadoran Military would utterly gut their ability to continue.

“The FMLN was beaten and forced to the negotiating table. It was their side that demobilized and turned themselves in to the Government Forces. We conducted the war in the way that should be recognized as a template for future conflicts. American casualties were kept to the very minimum and the GOES fought their own war. By any standard, the war was fought on a shoestring budget while the guerrillas were aided by multi-national Communist governments. The FMLN was aided by the Vietnamese, Cuban, Eastern Bloc, French, and even American Leftists.” — Leamon Ratterree, Operations & Intelligence, 3/7th Special Forces Group, note to author, September 5, 2021

In an eerie twist of irony as reported by Special Forces soldiers with access to Colonel Domingo Monterrosa, the first commander of the Atlacatl Immediate Reaction Battalion and who personally transmitted the Kill Order for the El Mozote massacre, the still popular and in fact venerated Salvadoran officer had been a paid Central Intelligence Agency asset. In his meticulous book on the El Mozote massacre, author Mark Danner wrote of the significant evidence that there were CIA assets monitoring the operation, Operation Rescate (Rescue) at the Salvadoran forward operating base camp at Osicala. A reporting cable obtained by Danner backed this up is included in the appendices of his book.

Two Special Forces mobile training teams had been involved in the training of the Atlacatl Battalion. The first led by then captain David Morris, the second follow-on mission commanded by then captain Dan Kulich. Despite early classes in the proper treatment of POWs by both teams, the Atlacatl under Monterrosa maintained “the only good guerrilla is a dead guerrilla” doctrine. During Operation Rescate no U.S. Special Forces soldiers were present in the field with the Atlacatl, nor at El Mozote when 900 men, women, the elderly, children, and infants were butchered. In the early years of the war, it was the CIA who were free to accompany Salvadoran units and to monitor their combat operations. Hence the Agency para-military Presence at Osicala on December 11th and the 12th, the two days during which the bulk of the mass killings were conducted. Knowing now that Monterrosa had been recruited early on in his career as a CIA asset the reason for the Agency presence in the field now makes reasonable sense. He was one of theirs and his success was critical to his continued value as he climbed the ranks and became the U.S. “go to” Salvadoran officer and face of the counterinsurgency.

RT Sidewinder was a Baru Montagnard team. Commanded by One Zero, now retired Major General Ken Bowra, as USASFC commander years later, would lend his name and influence to the combat recognition effort for those who served in El Salvador. (Photo courtesy MG (ret) Kenneth R. Bowra)

Lesson learned in Vietnam — the MACV-SOG Connection

By 1981, selected Special Forces soldiers with wartime experience in Vietnam were quietly receiving assignment to the 3/7th Special Forces Group (ABN) then at Fort Gulick, and later Fort Davis, Panama. Many of the senior non-commissioned officers had served with distinction with MACV SOG’s special projects. Others with the highly successful MIKE Force project and still others with the long-range reconnaissance teams, Ranger companies and the original DELTA project. Their names read like the Who’s Who in Special Forces — “Spider” Parks…Guy Wagy…Jim French…Joe Lopez…Steve Davidson…Jim “Sky” King…Carlos Parker…Larry Maker..Don Kelly…Leroy Sena.

These veterans of the most successful and dangerous special operations of the American war in Vietnam were meant to develop the younger generation of Green Berets filling the ranks at 3/7, the only forward deployed battalion from the 7th Special Forces Group (ABN) then at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. And they were purposely positioned in Latin America to take the fight to communist insurgents in El Salvador.

“We didn’t fit the mold. We just didn’t fit in. We were renegades used to operating independently, with few people pulling our strings. We disregarded the established rules and created our own. We did whatever the situation demanded, developed our own courses of action, never questioning the morality of what we did to survive and complete the mission.” Franklin D. Miller, Medal of Honor, Reflections of a Warrior

Projects DELTA and B-52 became the core structure for all other special/strategic reconnaissance projects deployed during the Vietnam War. DELTA teams specialized in raids against Viet Cong bases and lines of communication, as well as conducting hunter-killer missions against selected VC/NVA targets. In addition, DELTA developed the first deception operations meant to mislead the enemy about the intentions of friendly forces, and it conducted numerous photographic reconnaissance missions for tactical and strategic commanders. B-52’s responsibilities also included Allied POW recovery operations and targeting missions for the terminal guidance of airborne munitions. The groundwork laid by DELTA and B-52 would influence special operations for the duration of the war, and directly affect future special reconnaissance projects such as those which would be mounted in El Salvador decades later. So impactful were the men of MACV-SOG that the other projects that Special Forces teams deployed to the war in Afghanistan would request to wear specific Combat & Control North/Central/South team patches during their tours of duty. One operator explained it this way. “We all knew who these guys were and what they did. Wearing one of their team patches was our way of honoring their heroics and sacrifices. It also made us fight harder. We had a standard to uphold.”

U.S. Airpower – The AC-130 Factor

As the war began to turn against the FMLN in the field the guerrillas began to increase their operations, concentrating their attentions on American advisers because their vulnerability and high political profile made them handsome targets. As an insurgency, the war would only be brought to a successful conclusion by combining military methods with a broad array of economic, political, and diplomatic means.

A violent and massive escalation of the war by the FMLN in 1982 sent Salvadoran government forces reeling. Determined to split the country in half, guerrilla forces began battalion-size assaults on army cuartels at San Vicente, San Francisco Gotera, San Miguel, Usulután, and La Union. The two bridges across the Rio Limpa became primary FMLN targets, as well. On the ground, Special Forces advisers were working 18-hour days to improve the military capability of their assigned units, often accompanying them on limited forays “outside the wire” on patrols and company-size operations. Said one adviser “You cannot present yourself as a combat expert and then stay behind while your students take all the chances. It was no secret in country that we were in the field; they knew full well at the ambassador level what we needed to do to get the job done.”

Sergeant Joseph Vigueras, an SF adviser in 1988 to El Salvador, echoed the same earlier thoughts. “The only way an SF trooper can effectively evaluate soldiers is by actually participating in the training. Improvise, Adapt, Overcome. That was the only way to accomplish the mission.”

PRAL and 2/75th patches. Rangers from the 2/75th RGR Battalion provided extraction / recovery capability in El Salvador. (Photo courtesy Greg Walker)

Captain Jeff Nelson (Left) and author conducting airframe familiarization with PRAL students at Fort Gulick, Panama. (Photo courtesy the Greg Walker Collection)

Between 1981 and 1984, Special Forces mobile training teams from Panama had trained and graduated the Atlacatl, Atonal, Arce, and Ramon Belloso Immediate Reaction Battalions (BIRIs) with the Belloso the only BIRI trained out-of-country (Fort Bragg, NC). An A-team from 3/7th SFG(A) stood up the Salvadoran Parachute Battalion, a unit that ultimately included HALO qualified Salvadoran paratroopers. In what was a highly classified training mission, Company A, 3/7th, trained the first Salvadoran reconnaissance capability, the PRAL, at Fort Gulick, Panama. PRAL candidates were vetted and upon their arrival at Fort Gulick subjected to testing that included reading, writing, basic math, and the ability to swim. For the next 90 days, PRAL students learned how to conduct multiple special operations missions, spending only 20 days in the formal classroom environment with the rest of their time dedicated to navigating, living, and operating in Panama’s triple-canopy jungle environment.

Upon its return to El Salvador, the PRAL was turned over to Special Forces / CIA paramilitary advisers. The PRAL would go on to conduct special reconnaissance, often directing the paratroopers into guerrilla base camps hidden high in the mountains. From forward staging areas, U.S. advisers assisted in launching six-man teams using assigned UH-1H helicopters which were part of the PRAL “air force”. PRAL missions included not only battlefield intelligence gathering but surgical strike missions against targeted FMLN battlefield commanders and strategic sites controlled or occupied by the guerrillas. The PRAL would later be expanded to battalion size and retitled as the GOE, or Special Operations Group.

According to FMLN battlefield reports, the PRAL became worrisome and then feared. During one PRAL operation two recon men, dressed as civilians, infiltrated a 20-person guerrilla unit by claiming to be deserters from their army unit. For the next month they lived and traveled with the guerrillas gaining their trust. At the appointed time the two, now fully considered to be FMLN material, offered to teach a class on the M-60 light machine gun to their “compas”. At the conclusion of the class the two locked, loaded, and then used the M-60 to mow down the assembled guerrillas. They collected additional intelligence information and then made their way back to the PRAL compound outside San Salvador. In 1993, during a three-day visit with former FMLN guerrillas in San Francisco, California, this author spoke with one female commander about the PRAL. Her unit had been targeted by a PRAL recon team which called in multiple air strikes against their base camp. “We hated and feared them,” she told me. “They were like ghosts.”

By mid-1982, the Green Berets had carried out forty-six separate MTTs with the Salvadoran military. These included counter-guerrilla operations, planning and assistance, small unit tactics, field medical skills, patrolling, harbor security, arms interdiction, advanced photography, heavy weapons employment (e.g. – 90mm recoilless rifle, mortars), dam security, SCUBA operations, and human rights considerations. Still, by March 1984, the guerrillas were taking the fight to the Americans. During that month, two-man Special Forces communication teams assigned to critical Salvadoran election points throughout the country came under fire. In Honduras, U.S. Army Ranger platoons were pre-positioned and standing by with assigned aircraft support. The Rangers were to act as an extraction/body recovery element should the Green Berets come under attack and be unable to exfiltrate on their own. “We were to get them or their bodies,” remembers one former Ranger.

Harassing fire, sniper fire, and full-scale attacks against major Salvadoran military bases with Special Forces teams in place became commonplace. Such attacks occurred at El Paraiso, San Vincente, at the new Salvadoran training center in La Union, and elsewhere. Unknown to the American public at the time, Operation Bield Kirk provided for AC-130 gunships, based in Honduras, as well as AC-130 surveillance platforms, to the Green Berets under attack. The AC-130s would time and again for the course of the war respond to calls for help from the teams on the ground, devastating upwards of hundreds of guerrilla fighters who favored nighttime assaults.

One of the unintended consequences of Bield Kirk was to force the FMLN to order its field forces to cease gathering and moving in battalion size elements. Between PRAL recon teams discovering such movements and calling in Salvadoran air force assets and the Americans on the ground accessing AC-130 support from Honduras, the body counts being experienced by the guerrillas became staggering in numbers.

And the Salvadoran military, using its parachute battalion, began hitting those guerrilla columns trying to move their dead and wounded away from the killing zones. These immediate reaction efforts, as seen when the FMLN hit the training center at La Union, were deadly effective. Transported by the Salvadoran Air Force via the enhanced rotary airlift capability provided by the United States the Airborne battalion caught the attacking guerrilla force as it sought to escape, running them to ground and taking no prisoners. Former Force Recon Marine, Harry Claflin, recalls the paratroopers’ locating guerrillas in ravines around the training center and shooting them down like fish in a barrel. Much later, Bronze Stars for Valor would be awarded to Special Forces soldiers at those cuartels attacked and defended, in part, by the American advisers.

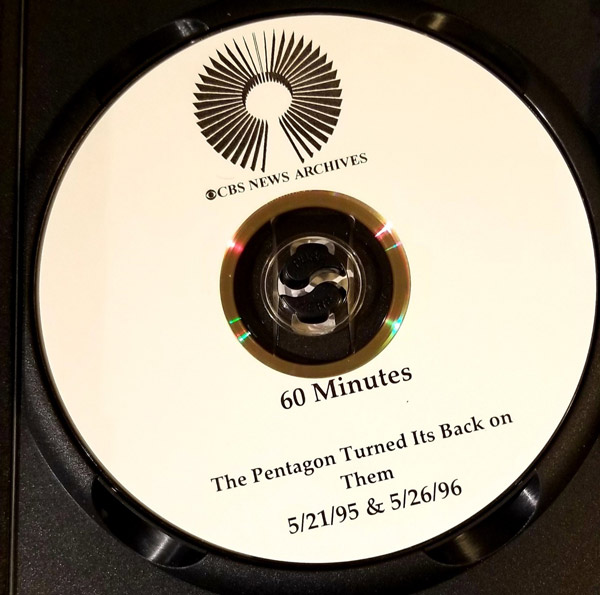

After 1985, the FMLN and its five separate armies in the field could no longer move in large numbers much less attack strategic locations due to the overpowering Salvadoran and U.S. air support. In a 1995 CBS “60 Minutes” report Ed Bradley explored the use of the AC-130 “equalizer” with Special Forces veterans of the war. The Pentagon, when asked, had no comment.

In 1985, during one memorable instance, Green Beret Robert Kotin secured an M-60 light machine gun while under heavy enemy fire at San Miguel. As Salvadoran military forces abandoned the base’s perimeter, falling back to the cuartel’s helicopter launch site, where both Kotin and a Marine Corps captain were dug in, Kotin began firing. “Kotin asked for cover fire from the Marine officer,” recalls Sergeant Major (ret) Bruce Hazelwood. “He [Kotin] then moved forward under fire and secured a position from which he could cover the retreating Salvadorans. This while slowing the guerrilla advance. The “Gs” had penetrated the base and were close to overrunning it until this took place.” With the SF trooper pouring fire into the guerrilla ranks, his Marine counterpart assembled a force capable of mounting a counterattack. Using Kotin’s outgoing fire as cover, the Marine led his ESAF stragglers in an assault that threw the guerrillas back.

Both Americans would be recommended for Bronze Stars for Valor, but only the Marine chain of command went ahead at the time and approved the BSM with V device for its officer. “The Marines maintained a separate service administration even from the U.S. MilGrp,” pointed out Hazelwood (himself a former Marine). “The Army downgraded Kotin’s award for purely political reasons, but the Marine Corps acknowledged the participation of their officer in combat without any negative feedback.”

Inter-Service support in-country, often unofficial and never reported, included the U.S. Navy SEAL platoon at La Union, in 1984, providing needed munitions to their SF counterparts then building the Salvadoran national training center. The 15-man MTT under the command of Major Charlie Zimmerman was advised by a PRAL recon team that a guerrilla force of 300 fighters were preparing to attack the essentially wide-open base. “We each had an MP-5, a .45 pistol, and about 100 rounds of ammunition apiece,” recalls one adviser. “We were in a ditch all night long, just waiting for the “Gs” to attack. One hundred rounds would to through a submachine gun pretty damn fast!”.

Afterward Colonel Joe Stringham, the MilGrp commander at the time, ordered the teams to arm themselves “with whatever you can get ahold of, just stay alive!”. Major Zimmerman had provided a detailed and thoughtful analysis, asking in part that his advisers be allowed to actively patrol the area around the developing base as a tripwire. Stringham, overriding the MilGrp attache’s objections, declared a zone twenty-five kilometers around the base to be a “training area”. Special Forces advisers began aggressive patrolling with their Salvadoran counterparts. The Americans drew brand new M-16s, M-79 grenade launchers, and M-60 light machine guns from the Salvadoran armory on base. In La Union, the SEAL platoon, having learned of the impending threat, unilaterally delivered Claymore mines, hand grenades, and additional rounds for the M-16s to the advisers. “Our primary concern was to be able to fight from inside the cuartel if attacked,” remembers one Green Beret. “But we had out people out in the bush conducting “training” both day and night. We went on patrols, capturing one guerrilla observer sitting in a tree observing the base.”

During one battalion-size training operation at this time, U.S. advisers with the Bracamonte BIRI already situated at the training base (CEMFA) turned the training mission into a 3-day combat op, targeting the guerrilla held town of Conchagua where the PRAL had confirmed the attacking force was assembling. Three companies of Bracamonte soldiers encircled the town and conducted a sweep. Green Beret advisers, armed with their new M-16s, accompanied them, including Major Zimmerman. “We had armed advisers in the field for over 24-hours,” says one of those Americans now long retired. “We just went with the flow.”

CEMFA would not be successfully attacked by the FMLN until the next rotation of trainers/advisers replaced the original MTT. In the aftermath of that attack five Green Berets would ultimately receive Bronze Stars for Valor in holding off and then throwing back the guerrillas. The new MilGrp commander, Colonel James Steel, would visit the badly damaged base the next morning as Salvadoran paratroopers and Harry Claflin hunted down the escaping guerrillas.

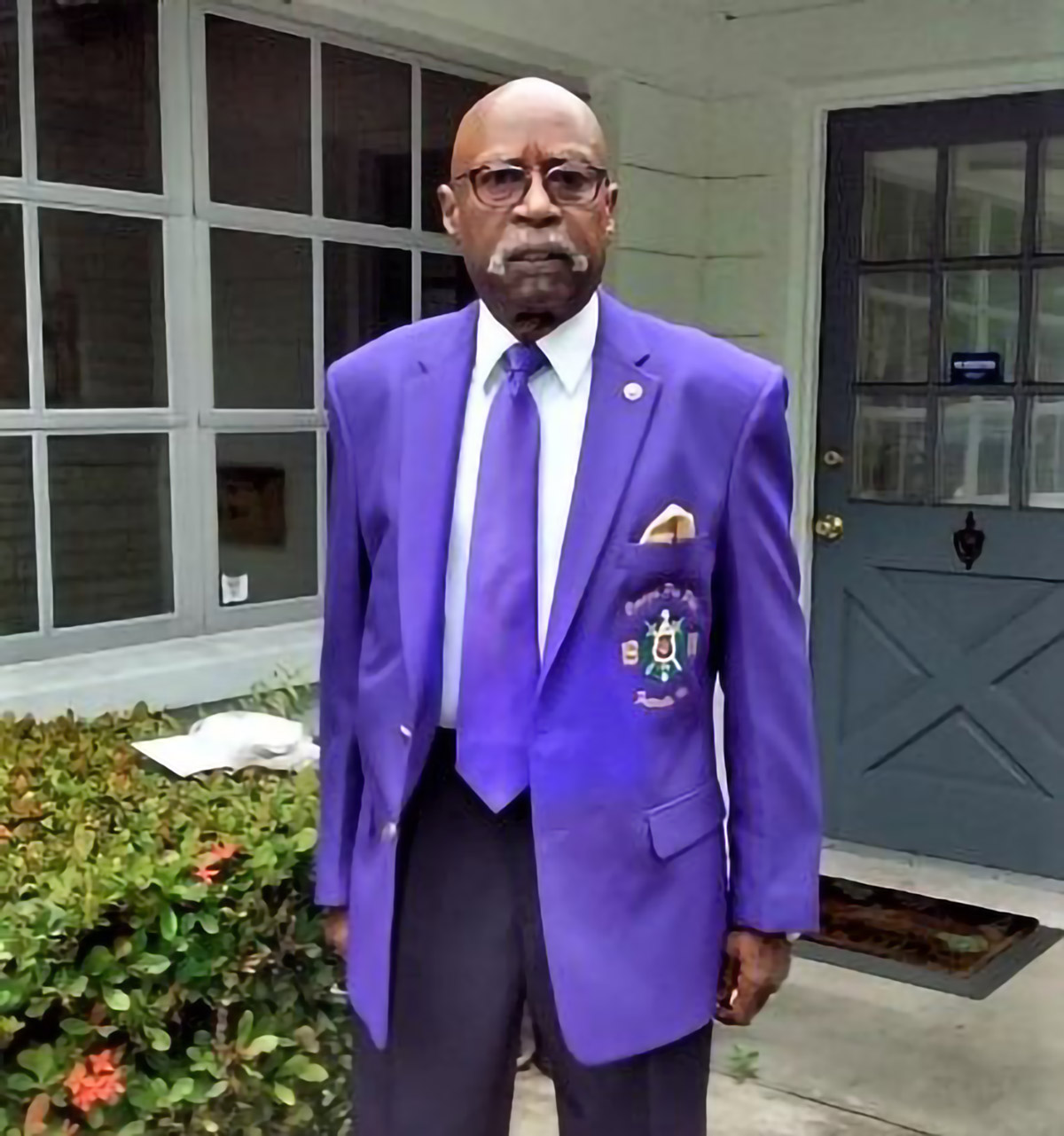

In an earlier clash with guerrilla snipers in and around CEMFA, MSG (ret) Hubert “Blackjack” Jackson would display the level of calm courage expected of a Special Forces soldier when he rallied the Salvadoran troops he was working with, the snipers ultimately driven off. Jackson, today retired and completing his Ph.D., would be recommended for and ultimately receive an ARCOM with “V” Device for his actions that day. He is one of the few African American “Green Berets” to have been so recognized for his actions during the 10-year war in El Salvador.

Master Sergeant (ret) Hubert “Blackjack” Jackson. (Photo courtesy the Greg Walker Collection)

Job Well Done

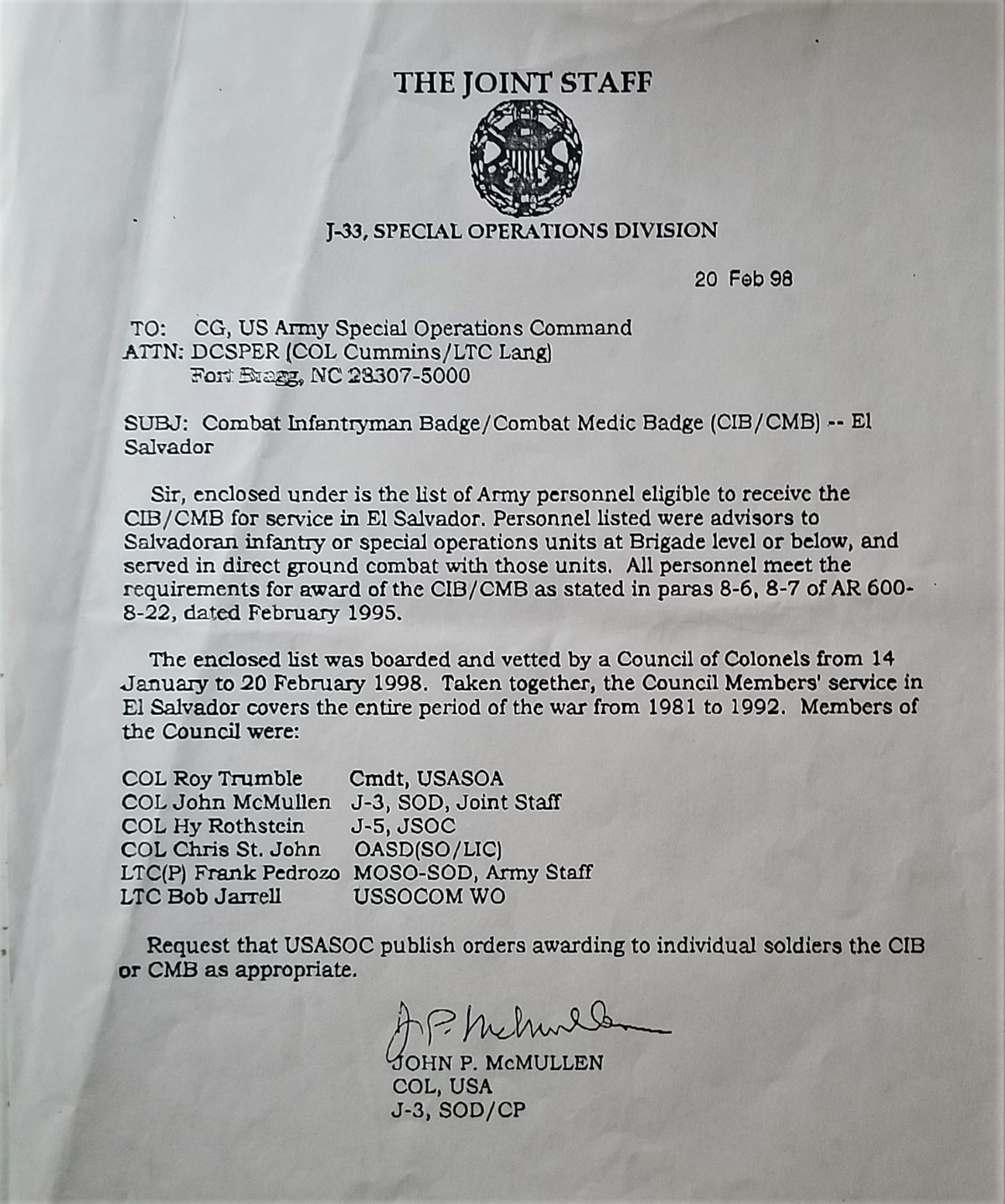

On February 20, 1998, Colonel John P. McMullen issued a formal memorandum to the Joint Staff regarding the award of the Combat Infantryman and Combat Medic badges for those who served in El Salvador.

McMullen, a veteran of the war himself, was co-founder of the Veterans of Special Operations – El Salvador. He convened a Council of Colonels from January to February to board all those names at the time who “…were advisors to Salvadoran infantry or special operations units at Brigade level or below and served in direct ground combat with those units.”

The process covered the entire approved years of the American involvement in the war (1981-1992). The criteria equaled the stringent considerations for the same awards for Project White Star (Laos). Over 80 recommendations were made, by name, to include the names of 11 non-SF personnel deemed eligible for the Combat Infantryman Badge.

McMullen, who the author was pleased to work for in Baghdad, Iraq, in late 2003 at the Coalition Provisional Authority, is the ultimate Quiet Professional. From 1989 until the U.S. Congress authorized full combat recognition and awards/decorations in 1996 for those who fought in El Salvador, it was John who fought the hard, lonely battles on our behalf even as he was still in uniform.

McMullen likewise located and often rewrote most of the early award recommendations for not only CIB/CMB consideration but for all those valor awards submitted to include the posthumous POW medal for Colonel David Pickett, shot down over El Salvador and then captured / executed by the FMLN.

Without now retired Colonel McMullen’s guidance, direction, insights, observations, and “Never Quit” attitude, what we accomplished on behalf of our wounded, injured, or dead as well as their families — and those who answered the call in El Salvador — would not have occurred.

Author (left) and Colonel (ret) John McMullen at Baghdad International Airport in late 2003. (Photo courtesy the Greg Walker Collection)

“To its great credit, the Veterans of Foreign Wars voted to petition the Department of Defense to award an Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal to the veterans of Central America’s longest war. Resolution 427 was unanimously approved during the VFW’s 93rd National Convention in August 1992. According to Mr. Richard Kolb, executive director of the VFW magazine at the time, the matter became a priority issue for the VFW in 1993. The resolution was drafted by the author in conjunction with the VFW chapter (1643) in Bend, Oregon.”

“De Oppresso Liber!”

About the Author:

Greg Walker (ret) served with the 10th, 7th, USASFC, and 19th Special Forces Groups (Airborne). He is a veteran of the war in El Salvador and Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Mr. Walker founded the Veterans of Special Operations – El Salvador, a grassroots fraternal organization that was at “the tip of the spear” in the 10-year long political campaign to see combat awards and decorations authorized for those who served, all Services, during El Salvador’s civil war. He is a Life member of the Special Operations Association and Special Forces Association.

His awards and decorations include the Combat Infantryman Badge (X2), the Special Forces Tab, the Meritorious Service Medal (X3), and the Washington National Guard Legion of Merit.

A DoD trained and certified Warrior Care case manager with the U.S. SOCOM Warrior Care program (2009-2013) Walker advocated for the most seriously wounded, injured, or made ill Special Operations Soldiers, Sailors, Marines, and Airmen serving during the Global War on Terrorism.

He is the author of At the Hurricane’s Eye — U.S. Special Operations Forces from Vietnam to Desert Storm (Ivy Books, 1994), among other literary contributions to U.S. SOF history.

Today, Greg lives and writes from his home in Sisters, Oregon, along with his service pup, Tommy.

Photo: Greg and Tommy

Leave A Comment