From Innovators Who Changed the World: Timeless Leadership Lessons From West Point, Green Berets, Sherlock Holmes, and Wall Street, Chapter 4:

Leadership Lessons from the Evolution of the Army Rangers

By James R. Webb

Reprinted with permission from Innovators Who Changed the World: Timeless Leadership Lessons From West Point, Green Berets, Sherlock Holmes, and Wall Street by James R. Webb, pages 73–90, published by Breakthrough Strategy, August 8, 2022.

Available for purchase at Amazon.com.

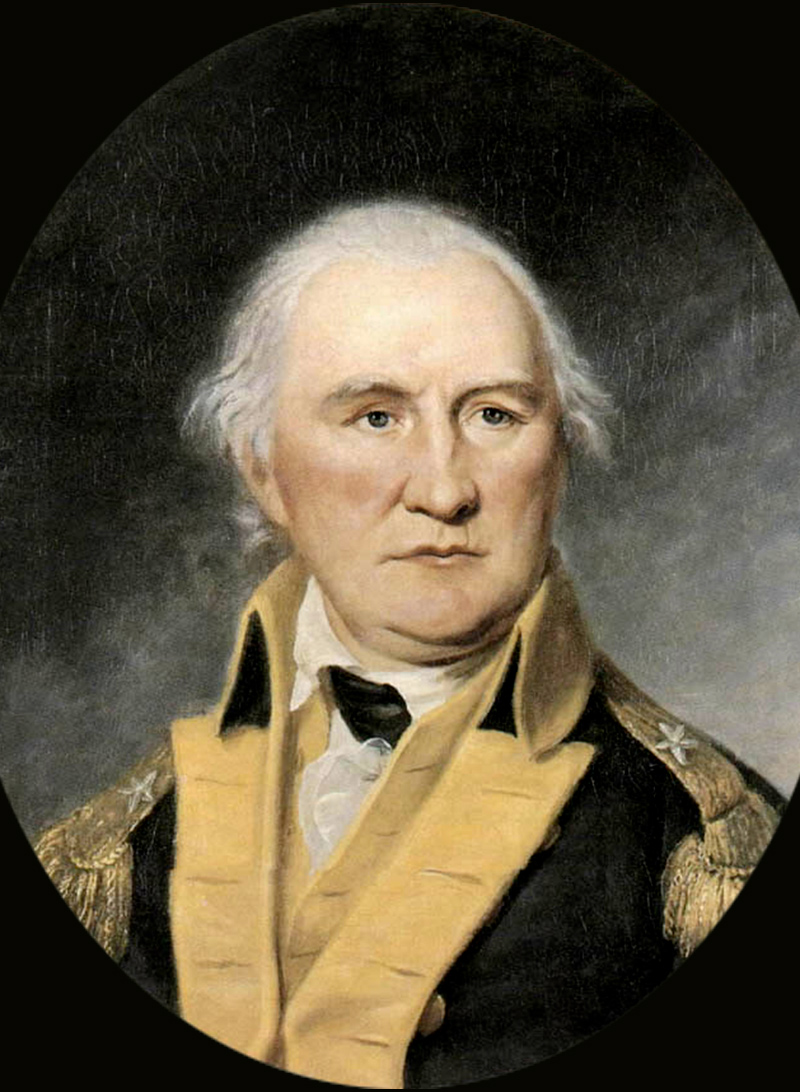

Major Robert Rogers of New Hampshire recruited and organized nine companies of American colonists. His purpose was to train them in ranger tactics to support the British in the French and Indian War. (Thomas Hart (publisher); Johann Martin Will (artist) — From the Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, Public Domain)

Major Robert Rogers of New Hampshire recruited and organized nine companies of American colonists. His purpose was to train them in ranger tactics to support the British in the French and Indian War.

Our innovative leadership journey now takes us to explore the US Army Rangers. The Rangers teach us how to always stay one step ahead of our competitors, how to prepare for any eventuality, and how to be flexible in the face of an ever-changing environment.

Early on, Robert Rogers learned from the tactics of the American Indians as he developed ways and means to defeat British forces in the American Revolutionary War. John Mosby became the “Grey Ghost” of the American Civil War as he and his men seemed to disappear into nowhere. More recently, Darby’s Rangers managed to attack positions in World War II that were previously deemed impenetrable. Rangers are not afraid to adapt to ever-changing situations and the challenges they present.

The history of the Army Rangers dates back to the 1600s and the arrival of the first people to eventually be called Americans following their arrival from Europe.

These first explorers and settlers seeking the New World brought with them the ways of Europe. More specifically, they were primarily schooled in the European method of engaging in warfare. In Europe, conventional rather than irregular warfare became the standard with its planned set-pieces and large numbers of soldiers lined up in orderly rows on clear fields of battle.

Large-scale religious wars had evolved into large armies led by professional officers. The officers hailed from the aristocracy and served to lead a collection of mercenaries combined with those in the lower classes of society. Since it was difficult to replace a trained army, battles of maneuver on a large field became the norm. Both sides would maneuver to gain a decided advantage rather than engaging in an affair that resulted in large-scale casualties and attrition.

This contained and controlled style of warfare was primarily done in good weather in order for generals to be able to adequately control troop movement. Tactics such as raids and ambushes were frowned upon and considered ungentlemanly.

Enter the New World. While Europe contained well-established cities, fields that were well cultivated, and had a relatively short distance between towns and countries, America had the opposite. The terrain was both vast and varied. In some places the forests were so dense as to be unpassable. Explorers experienced wild animals such as bears and wolves while swatting mosquitoes and fending off rattlesnakes.

Initially, newcomers to America settled by the sea as a source of food and transportation as moving inland proved to provide too many hurdles as to be practical. Eventually, countries such as France, England, and Spain realized the potential of the vast resources offered in the New World-resources such as timber for building, fur from animals, and fish.

As the European population swelled, they inevitably ran into the previous occupants of the New World: Native Americans. It is estimated that more than a million Indians lived north of what is now Mexico, with almost a quarter of those residing along the eastern coast. While numerous tribes existed, the most powerful tribe in the area of the colonists was the Iroquois.

The Iroquois were a warrior people who focused on conquest and controlled much of the land between Canada and the Carolinas. They were fierce fighters and featured canoes built specifically for war. Other tribes often looked to them for guidance and permission and sent tribute to maintain peaceful relations.

The Indian was a hunter, so war was a natural part of their existence. It had not evolved into the gentlemanly wars fought by the aristocratic kings of Europe. Indians would avoid planned battles fought in the open and favored the surprise of raids and ambushes. Given the distances between tribes and settlements, a small band would travel many miles over rough terrain to conduct a surprise attack upon their enemy.

They would hide behind trees rather than standing out in the open, and only pop up to shoot their arrows when they had the advantage on a tactical level. They blended into their environment and made the best use of the weapons they had, intending to inflict the greatest harm while minimizing casualties. The ultimate test of this warrior was bravery in battle. Their defeated enemy would suffer enslavement, torture, and the taking of scalps.

There were very cruel days on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. While the American Indians practiced their brutal way of war, Europeans practiced a class system that was ruthless in its approach. Powerful Europeans were known to flog, torture, and enslave those in the lesser classes, especially those with differing religious beliefs. Both sides—Europeans and American Indians—approached the other with trepidation and distrust.

As the new settlers expanded, they conflicted with the American Indians who did not practice the concept of private land and ownership. For the American Indian, the only owner of the land was the tribe that could hold it by force. Land ownership beyond that was not practiced. Europeans intended to acquire and own land, and that hunger was answered with raids by American Indians. European settlers in remote areas became terrified as they found themselves in the middle of cultivating a field only to be attacked by those who felt they were intruding on their way of life.

As hatred between the two groups grew, the European settlers formed units of citizen-soldiers based on a longtime English model to drive off the menace. Eventually, permanent military units were formed with forts built to protect land acquired and settled on by European families. The tension between the two sides increased, exacerbated by the emotions of people being killed on both sides.

New Rules of Warfare

Given the new terrain, new conditions, and their new enemy, the newly arrived Europeans were forced to reconsider their methods of warfare and adopt many of the tactics being used against them by the American Indians. The European method of lining up in an orderly manner in the middle of a field did not work against their new foe. The techniques the American Indians had used and refined over many years were carefully studied and copied. These methods and corresponding tactics led to the tools and techniques used by the early American Ranger.

The term ranger has been associated with those who ranged far into England’s dense and unexplored forests as early as the thirteenth century. The seventeenth century found the title being more frequently used in association with irregular military organizations such as the border rangers who guarded the harsh frontier border that England shared with Scotland.

John Smith (STC 22790, Houghton Library, Harvard University)

In the Travels and Works of Captain John Smith, Captain Smith often speaks of his men “ranging” in various areas. In the first instance he uses this term, he reflected on his encounter with Indians who had set upon his small group to steal his tools around 1608 while he was in Virginia. Initially, the White settlers would trade steel tools for food as they were not yet self-sufficient. Over time, they produced more food on their own so there was less need to trade away their precious tools.

Yet, the Indians craved the European tools as something very beneficial and did not have the knowledge to make their own. Theft became a viable option to them, as did the kidnapping of people to exchange for these precious tools. Such acts often led to both animosity and heavy retaliation, with muskets deployed by the new Americans against the bow and arrow of the Indian. Naturally, muskets also became a craved-for item, and the technology of warfare escalated as the Indians exercised their expertise in raids to acquire more.

By 1670, Captain Benjamin Church formed, trained, and led a unit that utilized ranger tactics. It was deployed against the Indians in 1675 in a conflict known as King Philip’s War. King Philip was the nickname of the chief of the Wampanoag peoples who was looking to force the English colonists from New England. These rangers were vital in helping the conflict result in a successful conclusion for the colonists.

Captain Benjamin Church (public domain)

In 1756, Major Robert Rogers of New Hampshire recruited and organized nine companies of American colonists. His purpose was to train them in ranger tactics to support the British in the French and Indian War. These ranger tactics were derived from the techniques and operations used by frontiersmen at the time.

What was different was that Major Rogers incorporated them into the doctrine of a standing organized fighting force. These companies brought together frontiersmen, hunters, mixed bloods, and Indians to scout and raid for British forces. They were officially dubbed the Ranger Company of the New Hampshire Provincial Regiment. The unit was known for being well trained and conducting daring operations that included deep penetration well behind enemy lines.

While they were disbanded after the war in 1763, they left an indelible mark on the history and traditions of the American military and are often considered the first genuine ranger unit as their organization and tactics were absorbed and built upon by subsequent ranger-type units.

Of particular interest were the Standing Rules of Rogers Rangers. While those interested can find all twenty-seven of the standing rules on the ranger.org website, some of the more intriguing examples are these:

- All Rangers are to be subject to the rules and articles of war; to appear at roll-call every evening, on their own parade, equipped, each with a firelock, sixty rounds of powder and ball, and a hatchet, at which time an officer from each company is to inspect the same, to see they are in order, so as to be ready on any emergency to march at a minute’s warning; and before they are dismissed, the necessary guards are to be selected and scouts for the next day appointed.

- Whenever you are ordered out to the enemy’s forts or frontiers for discoveries, if your number be small, march in a single file, keeping at such distance from each other as to prevent one shot from killing two men, sending one man, or more, forward, and the like on each side, at the distance of twenty yards from the main body, if the ground you march over will admit of it, to give the signal to the officer of the approach of an enemy, and of their number.

- If you march over marshes or soft ground, change your position, and march abreast of each other to prevent the enemy from tracking you (as they would do if you marched in a single file) till you get over such ground, and then resume your former order and march till it is quite dark before you encamp, which do, if possible, on a piece of ground which that may afford your sentries the advantage of seeing or hearing the enemy some considerable distance, keeping one-half of your whole party awake alternately through the night.

- Sometime before you come to the place you would reconnoiter, make a stand, and send one or two men in whom you can confide, to look out the best ground for making your observations.

- If you have the good fortune to take any prisoners, keep them separate, till they are examined, and in your return take a different route from that in which you went out, that you may the better discover any party in your rear, and have an opportunity, if their strength be superior to yours, to alter your course, or disperse, as circumstances may require.

- Before you leave your encampment, send out small parties to scout round it, to see if there be any appearance or track of an enemy that might have been near you during the night.

- When you stop for refreshment, chose some spring or rivulet if you can, and dispose your party so as not to be surprised, posting proper guards and sentries at a due distance, and let a small party waylay the path came in, lest the enemy should be pursuing.

- If you have to pass by lakes, keep at some distance from the edge of the water, lest, in case of an ambuscade or an attack from the enemy, when in that situation, your retreat should be cut off.

- If the enemy pursue your rear, take a circle till you come to your own tracks, and there form an ambush to receive them, and give them the first fire.

- When you return from a scout, and come near our forts, avoid the usual roads, and avenues thereto, lest the enemy should have headed you, and lay in ambush to receive you, when almost exhausted with fatigues.

Major Rogers continually drilled these standing rules into those under his command, including the conduct of live-fire exercises, until they were ingrained enough for them to execute bold, coordinated movements. What is noteworthy is that the practice at the time for conventional army units was to settle down into a bivouac during the winter months-not so for the rangers. They would continue to move against the French and Indians through the use of winter gear such as snowshoes and sleds.

Perhaps his most famous raid was against the Abenaki Indians whereby he directed a force of 200 Rangers over 400 miles, by both boat and land over a period of two months, to penetrate deep into Indian territory to devastate the Abenaki tribe. The successful raid resulted in the tribe no longer being a threat.

Rangers in the American Revolution and Beyond

More than a decade later, the need for rangers rose again as the American colonists prepared for war against the British. Anticipating a revolutionary war, the Continental Congress raised companies of expert riflemen in Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia. These companies drew heavily upon the experience of the frontiersmen that had practiced ranger tactics.

Daniel Morgan had joined a company of rangers during the French and Indian War and soon became familiar with the tactics used by such a unit. At the outbreak of the Revolutionary war, Morgan was given a command that was named the Corps of Rangers by George Washington and considered by the British to be the most formidable force fielded by the colonies. Morgan was successful because of his use of tactics such as blocking roads to slow British movement and using snipers to eliminate enemy leadership and scouts.

Daniel Morgan (public domain)

At one point, Morgan’s men dressed as Indians and used hit-and-run tactics to disrupt the British in New York and New Jersey. In addition, his riflemen were expert shots and used long rifles that could accurately shoot twice as far as the British muskets. Meanwhile, in Europe, future generals such as Napoleon continued to study how to maneuver large numbers of troops in large fields.

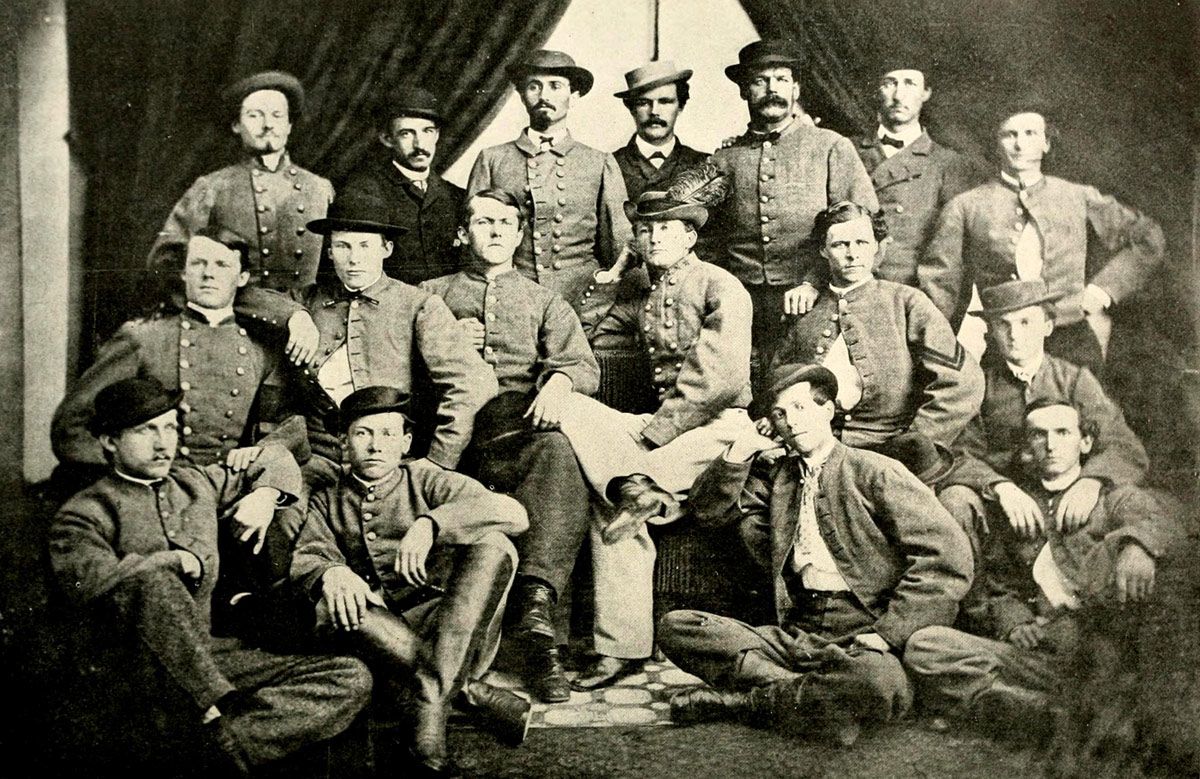

The American Civil War brought with it a variety of men who were well versed in ranger tactics. The most famous was John Mosby, who became known as the “Grey Ghost.” Mosby initially joined as a private in the Confederate Army and soon found himself scouting and running raids under the leadership of the audacious cavalry commander JEB Stuart seeking to disrupt communications and the flow of supplies to Union troops at the front.

Confederate Cavalry Colonel John S. Mosby and some of his men: Top row (left to right): Lee Herverson, Ben Palmer, John Puryear, Tom Booker, Norman Randolph, Frank Raham. Second row: Robert Blanks Parrott, John Troop, John W. Munson, John S. Mosby, Newell, Neely, Quarles. Third row: Walter Gosden, Harry T. Sinnott, Butler, Gentry.

Once his talent was recognized, Mosby was given command of the 43rd Battalion Virginia Cavalry and eventually designated as partisan rangers operating in Northern Virginia. Partisan rangers operated very differently from the regular Confederate Army at the time. They lived scattered among the civilian population rather than in army camps and enjoyed sharing the spoils of war. Essentially citizens by day and soldiers by night.

Early successes included a raid that resulted in the capture of Union General Edwin Stoughton. While the general’s unit was sleeping off a raucous party, Mosby’s rangers slipped into his camp and captured the general along with over thirty of his men and around sixty horses. It was reported that President Lincoln was less concerned with the capture of the young general than he was of losing that many horses, as horses were expensive and hard to acquire. This raid went far in improving the morale of the Confederacy, who were in the initial stages of food shortages.

Operating out of Middleburg, Virginia, Mosby’s rangers became masters at conducting lightning-quick raids that struck well into the rear of the Union forces and then disappeared as Union forces sought to capture them. All the men under his command were expert horsemen and more than familiar with their area of operations.

Perhaps most interesting about Mosby is that following the end of the Civil War, he became friendly with and actively supported Ulysses S. Grant in his former foe’s election as president of the United States. Even more intriguing because in the book the Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant, it was noted that in May 1864 Grant was traveling unguarded between Washington and his headquarters. Mosby missed capturing him by only a few minutes while on one of his frequent raids into Union territory.

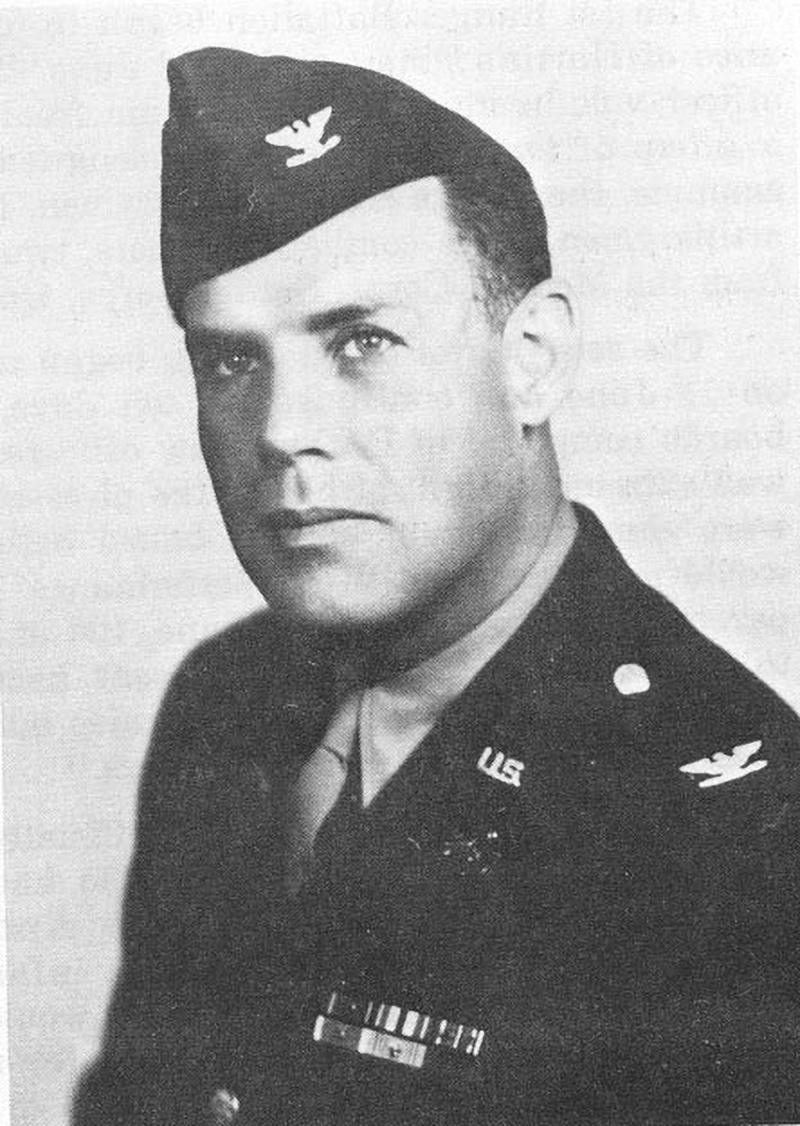

World War II brought the capabilities of the Ranger battalions into full focus. In the European theater they became known as Darby’s Rangers. In the Pacific they were called Merrill’s Marauders. In the European theater, Generals George Marshall and Lucian Truscott determined that, with America’s entry into the war, a unit be developed along the lines of the British commando model.

COL William Darby (U.S. Army)

The name “Ranger” was selected due to the long history of ranger activity in the United States, and also because the term commando belonged to the British. They chose Captain William Darby to lead the effort due to his outstanding reputation and experience with amphibious training. Darby carefully cultivated men from other American units stationed in Britain and subjected them to a strenuous weeding-out process.

The First Ranger Battalion was officially activated in Northern Ireland in June 1942. The unit then moved to the British Commando Training Center in Scotland, where over 500 men underwent more thorough training in commando tactics. Now a lieutenant colonel, Darby led his men to spearhead the invasion of North Africa by conducting a night landing in Algeria to seize two separate gun batteries and open the way for the First Infantry Division.

In Tunisia, Darby’s Rangers conducted successful behind the-lines missions to capture prisoners and staged a twelve-mile night march across mountainous terrain to lead General Patton’s efforts to clear the El Guettar Pass in Tunisia. The location in central Tunisia was located where several roads from the south and the coast came together, making it tactically critical. They captured several hundred prisoners in the process.

After Tunisia, two more Ranger battalions were formed and trained by Darby’s first battalion. This combined unit then spearheaded the efforts to capture Sicily and created a jumping off point for the invasion of Italy. The elite unit was the first to land in the invasion of Italy near Salerno.

Colonel Darby now had 10,000 men under his command, and he led them through bitter winter mountain fighting near San Pietro, regrouped, then spearheaded a surprise night landing at the Port of Anzio. These types of operations are typical of those given to Ranger units-constant movement through tough terrain to capture critical positions.

On another front, the 2nd Ranger Battalion was given the task of leading the assault on Omaha Beach in Normandy on D-Day, June 6, 1944. Under the command of Lieutenant James Rudder, they assaulted the perpendicular cliffs of Pointe du Hoc as German machine guns battered their ascent for two days and nights. Their successful mission destroyed a well-placed gun battery that could have taken potshots at the invading military fleets.

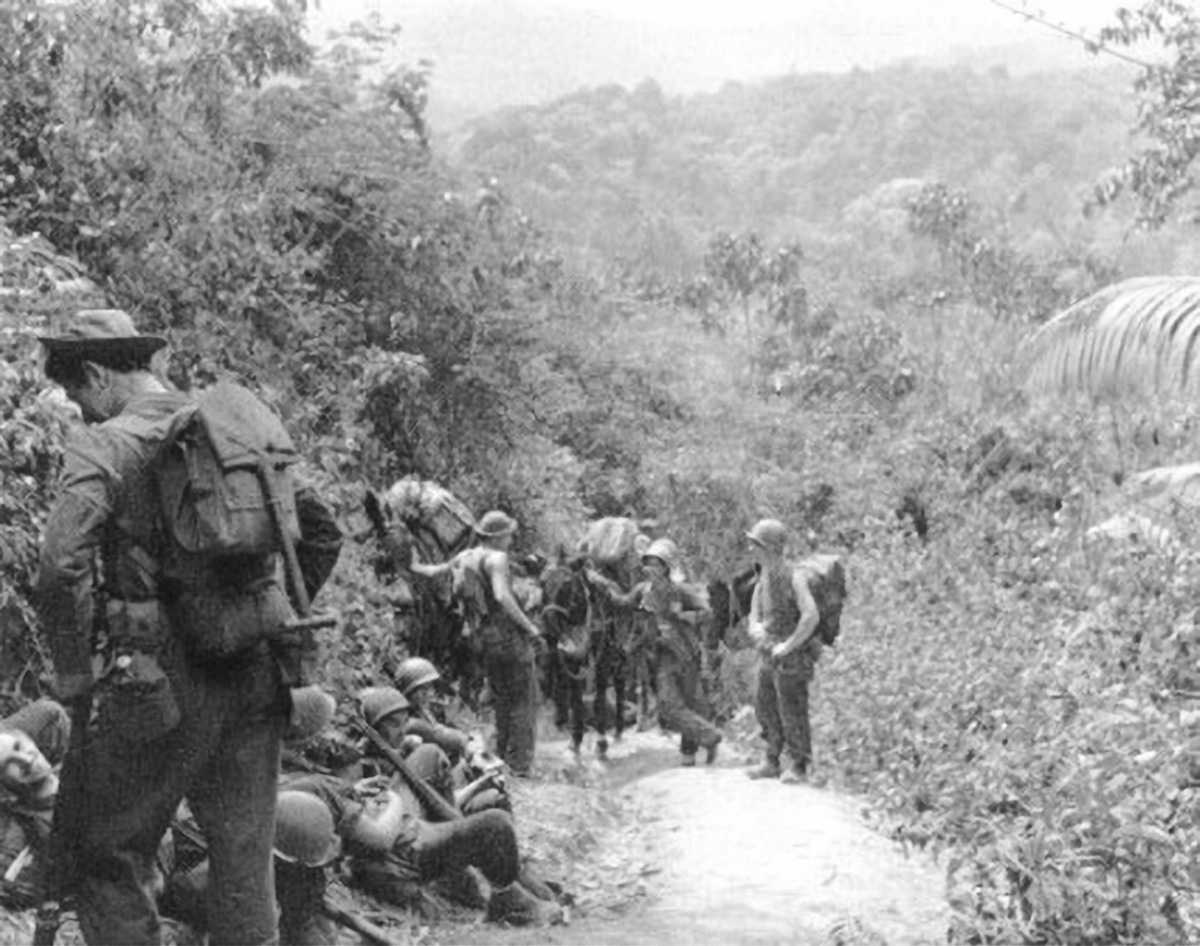

Merrill's Marauders rest during a break along a jungle trail near Nhpum Ga. (U.S. Army)

In the Pacific Theater, Rangers continued to distinguish themselves. As a part of the invasion that retook the Philippines, the 6th Ranger Battalion actively conducted raids and ambushes behind the lines against the entrenched Japanese Army.

In one of the most daring raids in history, an element of this unit marched thirty miles behind enemy lines to rescue 500 victims of the brutal Bataan Death March. Carrying many of these emaciated prisoners on their backs back to friendly lines, they managed to evade two Japanese regiments who were intent on finding them and killing their former prisoners.

Also, in the Pacific Theater was a Ranger-type unit designated as the 5307 Composite Unit, but better known as Merrill’s Marauders, named after their commander, Brigadier General Frank Merrill. The president put out a request for volunteers for a dangerous and hazardous mission.

Nearly 3,000 soldiers responded without knowing the true purpose of the new unit. Their task was to conduct a long-range penetration mission well behind enemy lines in Burma. Walking over 1,000 miles through rugged terrain, the unit distinguished itself by cutting off Japanese communications and disrupting supply lines. Vastly outnumbered, they eventually captured the critical all-weather Myitkyina Airfield. The unit was eventually redesignated the 75th Infantry, which is the current designation of American Ranger units.

From left to right, PFC Julius Cobb, Navy Gunner’s Mate Clarence Hall, British Army SGT Robert Hall, CPT Robert J. Duncan (in cart), and an unidentified Ranger pose with the carabao cart used to transport rescued POWs to Guimba on 31 January 1945. (U.S. Army)

Ranger units have since distinguished themselves in the Korean War, Vietnam, the Middle East, Grenada, Panama, and are even heavily used to support Special Operations activities. For example, they were on the ramp and ready to support the later stages of the Iranian hostage rescue attempt, Operation Eagle Claw in 1980.

Ranger School

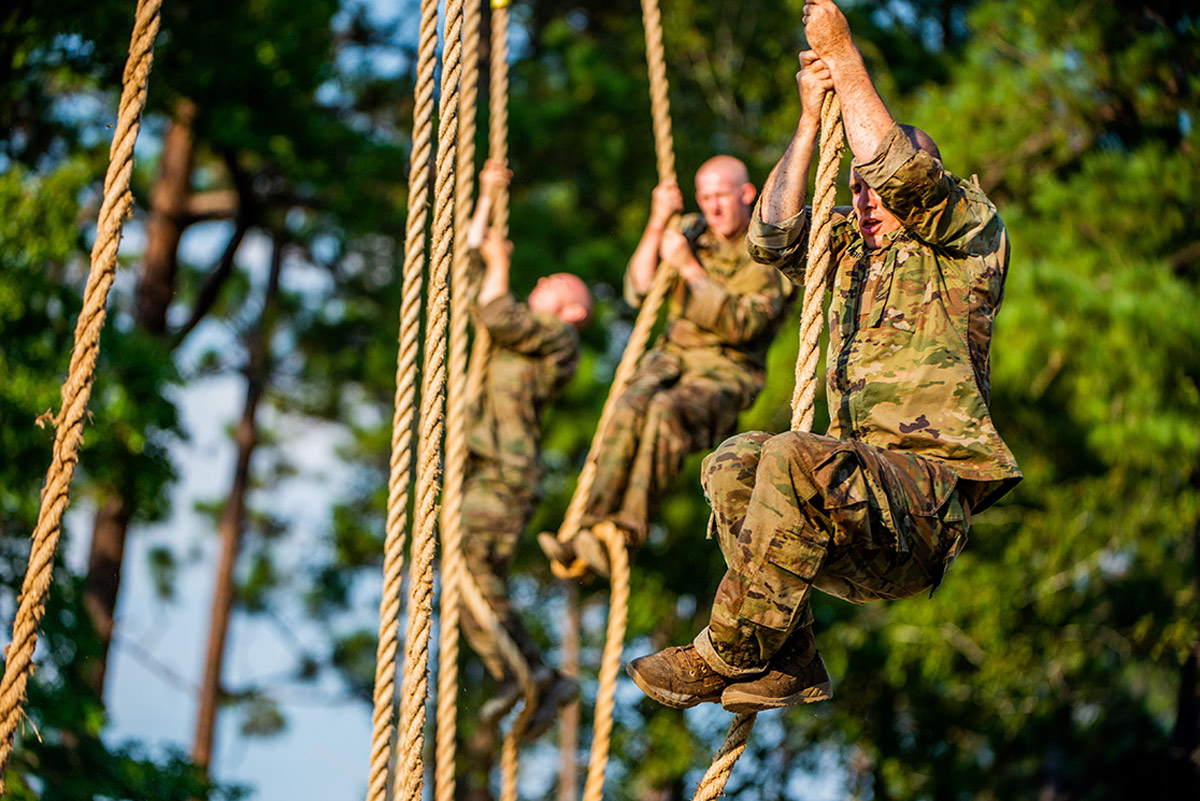

Ranger School is probably the most physically and mentally challenging course that most military personnel encounter in their lifetime. Well, at least for those who volunteer for the most demanding sixty-two days of their lives, and soldiers must volunteer.

To be accepted into the school you had to be in top physical condition, mentally tough, and highly motivated to succeed. Even then, only about half of this elite group successfully make it through to graduate and receive the distinguished Ranger Tab. The school itself is conducted in three phases: the Benning Phase located at Camp Darby in Fort Benning, Georgia; the Mountain Phase located at Camp Merrill near Dahlonega, Georgia; and the Swamp Phase located at Camp Rudder on Eglin Air Force Base, Florida.

The first phase, the Benning Phase, covers the basics of operating efficiently at the squad level. An infantry squad typically has nine soldiers. This initial part of the training is also focused on ensuring that the Ranger candidate has the physical stamina, mental toughness, and leadership abilities to be successful in the course. The physical standard is to be able to do fifty-eight perfect pushups, sixty-nine perfect situps, six perfect pull-ups, run five miles in under forty minutes, and finish a twelve-mile march with a thirty-five-pound rucksack in less than three hours. The word perfect was used in the previous sentence as the grader will not give credit for, say, a pull-up unless the candidate went all the way to a dead hang and then placed their chin all the way over the bar.

A land navigation test is given whereby the candidate must navigate to different points on a course using only a map and compass. Part of the navigation course is completed in darkness without using a flashlight. Precise navigation becomes critical during later phases as squads and larger attacking elements must assault a target at a specific place and a specific time or fail the patrol.

In addition, the fundamentals of patrolling are taught to include reaction drills (such as reaction to ambushes, contact, or indirect fire) and how to prepare and give warning and operations orders as a patrol leader. A Ranger candidate’s days are long and filled with repeated practice to firmly instill the fundamentals. Successful completion of this phase enables the Ranger candidate to move to the next phase.

A ranger instructor explains to company of rangers the technical instructions of rappelling from the 50 ft rock to his left in Dahlonega, GA, during the Mountain Phase of training. (Photo by Master Sgt. Cecilio Ricardo, U.S. Army)

The Mountain Phase starts with several days of military mountaineering training such as rappelling and climbing. The following two weeks are spent conducting raids, ambushes, and other patrolling missions over mountainous terrain. The harsh terrain provides an extreme challenge to the Ranger candidate as their stamina and commitment are stressed to extremes.

As a leader, the Ranger candidate is required to lead a group of tired and hungry soldiers over harsh terrain to their objective while maintaining strict military discipline, often in severe weather, while being harassed by a local aggressor force that is accustomed to the terrain.

Airborne qualified soldiers may find themselves parachuting into small drop zones on the side of a mountain, quickly assembling and organizing, and then moving off to accomplish their objective. Successful completion of this phase enables the Ranger candidate to move to the next phase, which for airborne qualified soldiers meant parachuting into Eglin Air Force Base. Non-airborne qualified candidates endured a long bus ride.

The final operational phase of Ranger School is the Swamp Phase. After completing the Mountain Phase, Ranger candidates are thrown into an environment of waterborne operations such as small boat movements and stream crossings. They also live in the swamp for the next few weeks and are trained to survive in a harsh environment that includes being constantly wet and sharing the ecosystem with poisonous reptiles and alligators. This is accomplished while constantly on the move conducting a variety of increasingly complex operations, having little time to sleep, and little to eat.

The endurance and mental toughness of each Ranger is thoroughly tested. Successful completion of this phase earns the Ranger a trip back to Fort Benning where they receive the coveted black-and-gold Ranger Tab that is worn above their unit patch on the left shoulder for the remainder of their service career.

I was fortunate in achieving the highest ratings in the class and being designated as the class Distinguished Honor Graduate. This came with a letter signed by a two-star general telling your commanding officer of the accomplishment-not a bad way to start a new job.

Innovative Leadership Lessons from Rangers

As tested by the Ranger School, the history of the Army Ranger has indicated an individual who is mentally tough, physically strong, and extremely motivated to ensure their given objective is met. The initial part of Ranger School is designed to provide the students with good habits and reinforce those habits with constant repetition.

This instruction is well designed, progressive, and sequential. Once a foundation is established, those habits are tested with a variety of continuous combat patrols that include little food or sleep.

As the Ranger student moves waist-deep through the murky swamps of Florida, often bordering on hypothermia with their shivering body keeping them awake, they come to know the very limits of their endurance. While tactical and technical competence is being built and embedded in the psyche of the Ranger student, so too are the leadership lessons that come with them.

At the beginning of the patrol, the appointed leader provides an operations order that details every aspect of the mission at hand. In this way, every Ranger student knows precisely what is expected of them. As missions become more complex, contingency planning becomes a key element as Rangers prepare for the inevitable changes and have the guidance to adapt accordingly.

Rangers are well known for quickly adapting to ever-changing mission priorities and tactical opportunities. Most operations do not come off exactly as planned, and the more complex the operation, the higher the risk of mitigating circumstances. Rangers are trained to anticipate and quickly adapt to this change. It has been said that in a period of rapid change, many tend to shirk responsibility. Rangers are taught the opposite-quickly identify the problem, step into the breach, and assume responsibility.

Leaders accept responsibility for both their actions and the actions of those they lead. Bad habits such as procrastination and selfishness are quickly cast aside as Rangers focus on those they lead and the mission at hand.

By focusing on those you lead, you can learn from their areas of expertise, promote their achievements, and understand how to best lead the group to accomplish the mission. This is the best way to make the right decisions under challenging circumstances. Those who wander into a situation unprepared, who fail to let those they lead know how they can contribute to success, and never bother to get to know the personalities and capabilities of those assigned to them, fail more often than not.

Equally important is that after completing Ranger School, the successful candidate knows substantially more about themselves. Socrates is quoted as saying, “To know thyself is the beginning of wisdom:’ The Ranger student is certainly going through a phase whereby they experience extreme tests to better know their personal capabilities. They have been tested physically and mentally. They have endured weeks of starvation and sleep deprivation, were pushed toward their physical limits, and stressed—all while being evaluated by Ranger instructors who are brutal in their assessments.

Your inner character becomes readily apparent to yourself and those around you. The best teammates were those who made everyone around them better, instilled confidence, understood the value in everyone, and knew that success was often something that needed to be negotiated. Also, the best teammates were not always those with the highest rank—they were the ones who inspired others and had a bias toward responsible action. As a result of all of this, there is a sense of strong comradery among graduates of the program.

In the 75th Ranger Regiment, there is a high level of trust in your fellow soldiers knowing that they have successfully completed this intense training, more so than in most other military units. That level of trust and comradeship becomes especially valuable in times of extreme stress, such as an armed conflict.

The sense of trust and comradeship found in the 75th Ranger Regiment also spills over into how they behave as a group. In my time assigned there, there was a strong sense of not wanting to disgrace the regiment through any personal actions. One of the mantras of the unit I was with was that they would always leave a training area in better shape than when they first arrived-and they always did. A strong sense of pride was gained by being assigned to such an elite unit.

Another of the lessons to be found in Ranger School is the power of preparation. From the very beginning, Rangers are trained to give detailed warning orders and operations orders that provide every person under their command everything they need to know for the mission to be successful. This thought process includes contingency plans should obstacles to meeting the objective be encountered.

Once the verbal ideas are conveyed, key activities are practiced until near perfection. These steps provide everyone involved with a high sense of inclusiveness and confidence. Preparation for Ranger School itself often weeds out those who do not anticipate this lesson as only those with the highest degree of physical shape and motivation will likely graduate.

This intense preparation also helps when things seem out of control. As mentioned previously, the best-laid plans will undoubtedly take a few turns. When that happens, the leader must quickly assess what they can control and what they cannot control. Stop worrying about activities beyond your control and focus on what limited recourses are at your disposal toward a modified plan that will meet the objective.

Many boundaries are self-imposed, and it takes a degree of self-awareness, and a great deal of humility, to realize what is really outside your realm of control and move toward a successful outcome. You can make a real difference as a leader by taking the initiative, encouraging those around you, and getting their minds off what is not going according to plan.

After successful completion of Ranger training, graduates receive their Ranger tab during their graduation at Fort Benning, GA. (U.S. Army photo by Staff Sgt. Steve Cortez)

In his book Only the Paranoid Survive (1996), Andy Grove describes a critical time at Intel where they were forced to acknowledge the realities of the marketplace. Intel had initially grown, thanks to the manufacture of memory chips for mainframe computers, but had also developed the first general purpose microprocessor for a digital watch. The microprocessor soon became the brains behind the personal computer.

While the company was an innovator in the memory chip market, the Japanese had begun to dump memory chips into the American market at below competitive prices. It was a tough decision for the leaders at Intel to abandon their long successful line of memory chips. They asked themselves what a new leadership team would do if faced with such a dilemma. The answer would be to get out of memory chips and focus on microprocessors.

As a show of solidarity and a change of direction, the team walked out of the boardroom, turned around, and walked back into the boardroom as a new team and immediately took steps to get out of memory chips and move full force into microprocessors.

Letting go of a product line in which you were the acknowledged leader for so long is tough, but the decision they made to know their internal capabilities and recognize the future was a sound one. They remain the dominant producers of microprocessors for personal computers. Intel also became one of the most valuable brand names in the world.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Jim Webb, educated at West Point in engineering and leadership, served as a Ranger and Green Beret. He has received an MBA, an MS in Engineering, and a doctorate in innovation. His career has included working as an R&D engineer for Texas Instruments, two decades of consulting in strategy and innovation with Price Waterhouse, Deloitte, and Kearney, being the Chief Strategist of two global companies, and managing a $6 billion pension fund. He is currently a Professor teaching strategy and innovation courses at Southern Methodist University.

He started practicing judo at a young age. He went on to win several national championships, as well as earning certification as an international referee and international coach. He served as the president of the US Judo Association, and is currently a director on the US Olympic Committee’s National Governing Body. He holds eighth degree black belts in both judo and jujitsu.

Timeless Leadership

Episode 44—Innovators Who Changed the World with Jim Webb

Check out Dr. Webb’s interview on the Timeless Leadership podcast, Episode 44 available at most major sources for podcasts.

Click here to find it on Apple Podcasts.

Click here to find it on Spotify.

Leave A Comment