CHAPTER THREE, Section A

II CORPS AND THE BATTLE TO SPLIT VIETNAM Part II

By Joseph Patrick Meissner

From The Green Berets and Their Victories, Chapter Three, published by Authorhouse, November 21, 2005, pages 81-90, reprinted with permission.

A. Cowboy Who Wore a Sneer on His Face.

For one hundred days II Corps had been unusually quiet. The tide of the Tet Offensive in February 1968 had receded. The May Cities Campaign, though destructive, had not been half as critical as Tet. But neither of these huge Red efforts had really affected the Green Beret ”A”-camps located away from the heavily populated areas that had been the targets of enemy attacks. Then in late August the Communists launched their third major offensive of 1968, only this was aimed at American military installations, particularly the Special Forces ”A”-Camps.

On a misty rainy night at 0330 hours of 18 August an NVA regiment hurled itself against both the east and west walls of Camp Dak Seang, north of Kontum city. For an hour and a half the defenders fought off wave after wave of fresh well-equipped enemy troops. Once the Communists even pierced the main perimeter. Inside the besieged bunkers indigenous wives carried ammunition to their husbands in scenes recalling the American colonial frontier. Because of the fog and strong winds Allied air power was virtually useless although a lone AC-47 circled high above the camp and dropped flares which dimly lit up the inky blackness. Just before dawn the NVA withdrew, dragging away their dead and wounded.

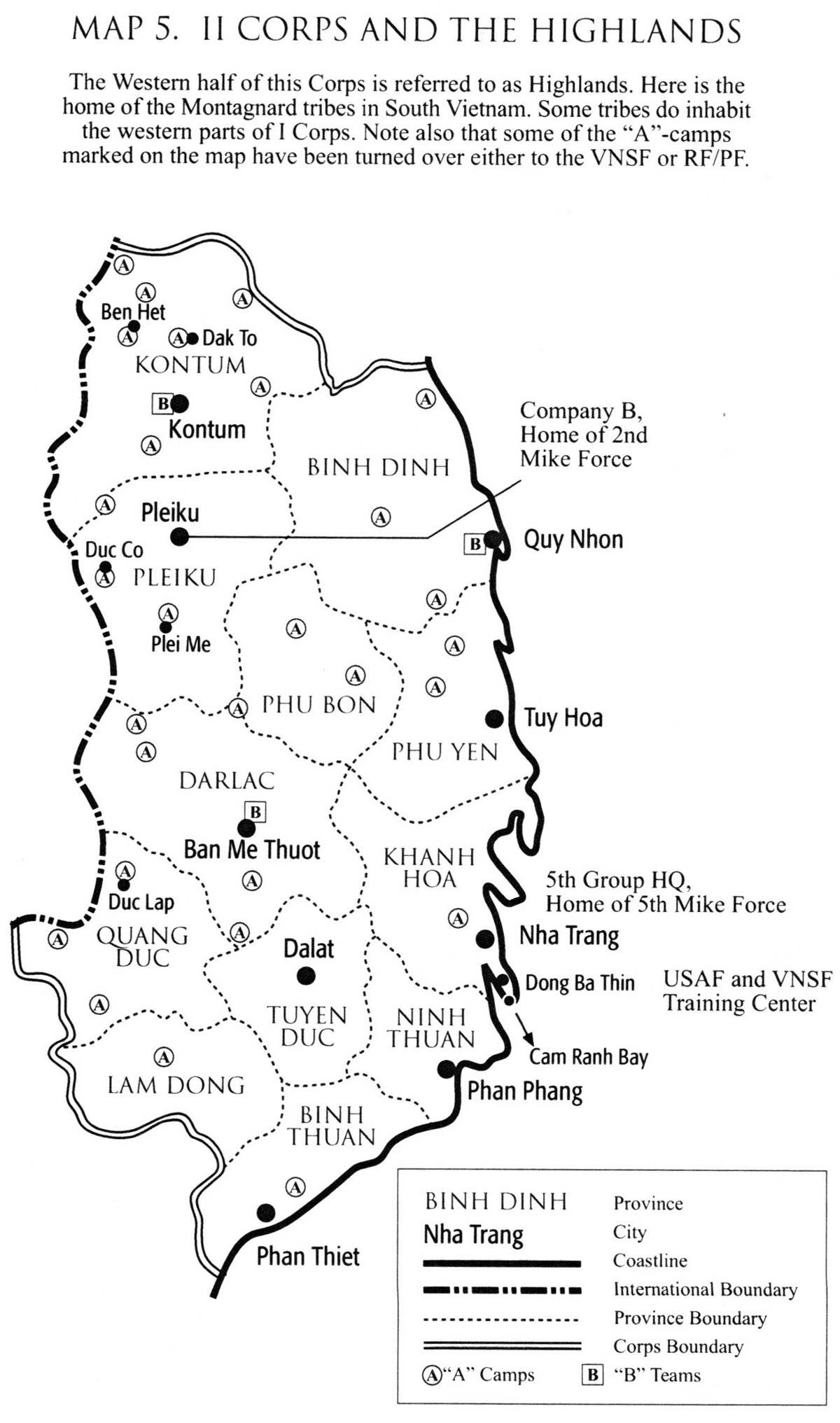

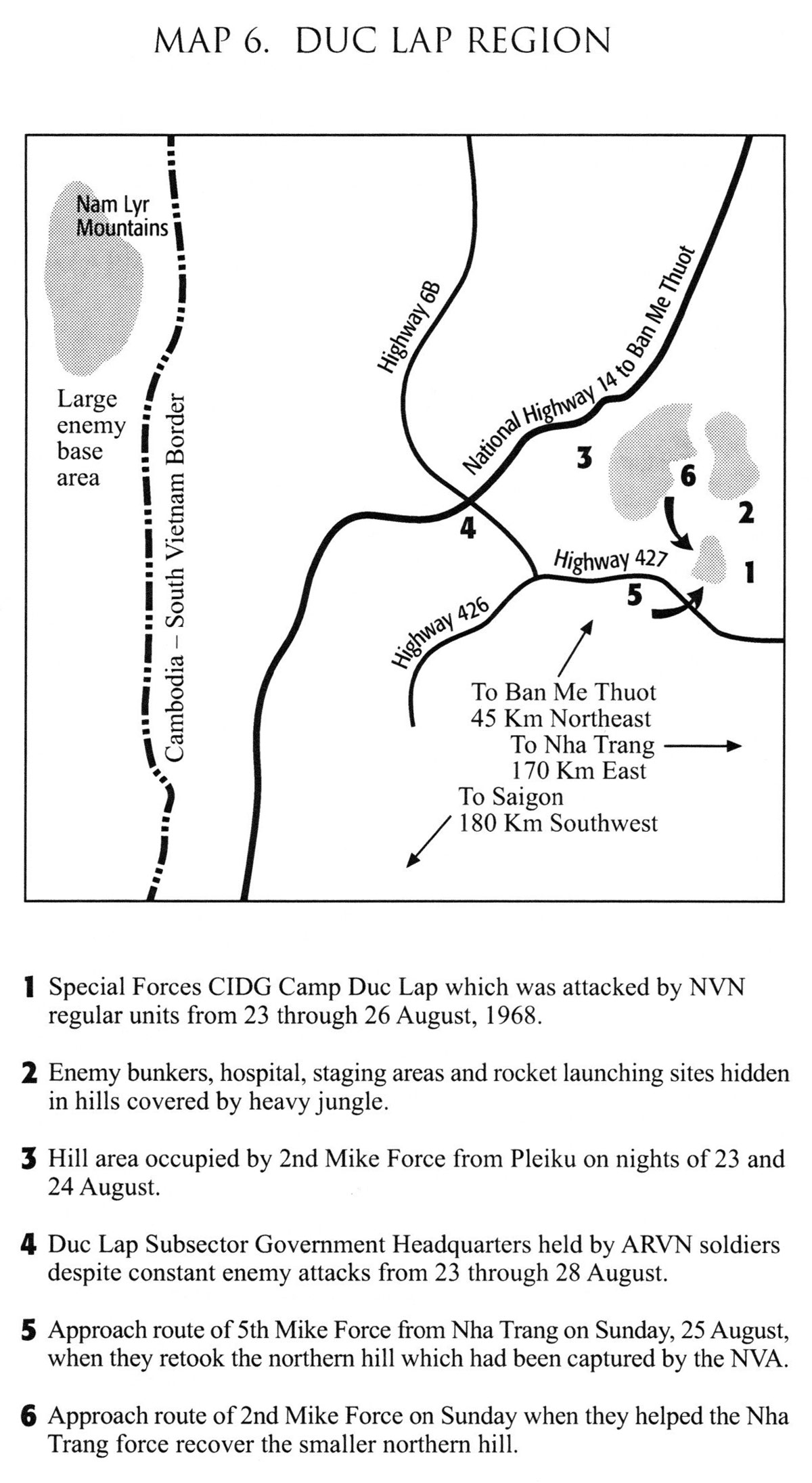

Dak Seang was the prelude for the battle five days later when three NVA regiments would assault Special Forces Camp Duc Lap and the local Government Headquarters in what would be the most significant battle the Green Berets waged the entire year. Camp Duc Lap, only ten miles from the Cambodian border (see Map 5), sits on two hills overlooking a plateau floor that stretches at least fifteen hundred meters in all directions. Four miles to the northwest is the local Government Headquarters astride the junction of two highways. (See Map 6 for Duc Lap area.)

Agriculturally the region is self-sufficient. The rich soil will yield virtually any crop that is planted, including rice, coffee, bananas, oranges, and sweet potatoes. Livestock and fowl are plentiful. The people enjoy a high standard of living compared to other areas of the country and during lulls in the war they transport much produce along Highway 14 for sale in the Ban Me Thuot markets. Most of the population are Vietnamese who fled Ho Chi Minh’s northern paradise and were resettled in the Highlands in 1956 as part of President Diem’s plans for incorporating the refugees within his newly born republic. Also dwelling in the Duc Lap area are Montagnards. The 1966 National Census showed 6,233 ethnic Vietnamese and 976 Montagnards. Almost half these people are Catholics while one-fourth are Buddhists and the remainder hold various animist beliefs.

Duc Lap District sits in what the Viet Cong call the “F6 Corridor.” This infiltration route starts in Cambodia in the Nam Lyr Mountains where the NVA have huge supply and troop bases, crosses the border, divides to fork around Camp Duc Lap, and then remarries to flow into “VC Valley” a long-time enemy base within Vietnam. A northern off-shoot of corridor extends to a Communist safe area near Ban Me Thuot. In the bureaucracy Duc Lap District falls under the control of VC Province whose home seat is VC Valley. North Vietnamese troops come down by truck along the Ho Chi Minh trail and stop in the Nam Lyr Mountain base. Then proceeding across the border through the F6 corridor they to rest in VC Valley before infiltrating deeper into the eastern provinces of II Corp or turning south into III Corps.

During July and early August of 1968 Green Beret intelligence sources had indicated an upcoming attack. Enemy troops had been spotted moving into the region in small units, their rucksacks heavily loaded down. This suggested rocket and mortar ammunition was being stockpiled for a battle. Just the week before, the “B”-team at Ban Me Thuot had raced Duc Lap Camp “Number One” on the list of camps that should expect to be hit. This week the camp had dropped to the “Number Three” spot. The enemy was a week late.

Sergeant Mike Dooley had radio watch chat night in the team house of the Camp. In his spare moments he was a cartoonist. With a few strokes of his pen he could make others laugh at the absurdities of this war. Three days later his body would lie slumped across the inner wall of sandbags. Buried deep in his brain would be a sniper’s bullet. Boody, the top sergeant, sat near Dooley. Boody was good looking with a ready ability to talk easily and smoothly. From the wreckage of the camp after the battle his weary unshaven face and husky voice would be broadcast across ten thousand miles of space to flash on the TV screens of America and tell folks back home what war was like. Boody was busy writing a letter to his wife before turning in. Other team members lounged around, some reading, others just finishing a card game. A few were sleeping in their well-fortified bunkers. The remainder of the team was advising two companies of indigenous troops on extended operations some twenty miles northwest of the camp.

Meanwhile two hundred feet from the camp’s northern wire, a lamp’s light flickered in the small command bunker. The NVA officer smiled to himself as he examined the map of the camp so carefully drawn in ink. Outside in the moonless night the rocket and mortar teams had already taken their positions around the camp. Nobody had been discovered. The attack would be a complete surprise.

For days before, enemy agents had surveyed the camp’s outposts and noted the CIDG guards lolling in the shade. Neither Americans nor VNSF ever seemed to accompany local security patrols. Moreover, the enemy had noted a set pattern of where these patrols went and where they did not. Slipping through the holes of friendly defenses, the NVA soldiers had built dozens of two and three man bunkers roofed over with heavy timbers within meters of the camp perimeter. How amazingly similar were such tactics to those used in the 1965 attack on Camp Plei Mei! Or further back, Dien Bien Phu in 1954!

The NVA officer pointed to the smaller northern hill of the camp on his map. “Here,” he said to his companion, “we will breach the wire at this point. You will lead the first assault tomorrow after dark.”

Where did they get the map? Lieutenant Harp, the “A”-team commander at Duc Lap, never liked all the civilians who walked about the camp, entering and leaving as they pleased. Time and again he had warned his counterpart, Captain Bao, who was Camp Commander, about the danger. But the camp was too near the surrounding villages and everybody had friends and relatives they wanted to visit. So Captain Bao was reluctant to do anything which would antagonize the people, and Lieutenant Harp (of course!) could not act because he only advised.

The enemy officer folded the map and stuck it into his pocket. He glanced at his watch. “One-fifteen, time to begin,” he said, “it will be a glorious victory.” Five days later an American sergeant leading a sweep after the battle would discover the officer’s corpse and find the map in his pocket. In one corner written in Vietnamese the dead man had composed a two line poem!

“Brothers, North and South, bravely battle the Americans,

The voices of victory spread like flowers in bloom.”

5th Group “Mike Force” line up in formation.

Suddenly a familiar dull rumble awakened Lieutenant Harp as he lay resting in his room. Mortar rounds were exploding somewhere in the distance. Boody heard them too. Opening the heavy wood door of the team house, he stood there, watching the flashes of light in the west popping around the Government Headquarters.

“Everybody up! Get out of bed!” Harp yelled through the night.

Childs, Hall, Alward, Shepherd, and the other Green Berets dressed and raced for the team house. Harp was already there. A message was coming in from the beleaguered Government Headquarters. Mortar shells were crashing all around them and they needed help. Boody called the “B”-team at Ban Me Thuot to inform them and ask for Spooky, the huge lumbering AC-47 gunship whose mini-guns had smothered so many past Communist attacks on Allied outposts. Harp told the rest of the team to get their troops organized and man their alert positions.

“We thought we were really sitting eight then,” Boody observed later, “we thought nobody would fool with us.”

But the NVA did not agree. Fifteen minutes after the opening fires struck Government Headquarters, rockets and mortars slammed into a tiny Camp outpost which protected the runway. Quickly, the enemy attack reduced the OP co a pile of rubble. Now it was the camp’s turn. Small arms and automatic fire rattled through the night, building to a crescendo of mortar rounds and B-40 rockets which smashed and splattered against friendly fortifications. All night the attack continued, slackening only at dawn. But when a Camp Strike Force patrol attempted to leave camp, enemy fire cut through its ranks and sent the soldiers scurrying back within their defenses of barbed wire and sandbags. Like mushrooms enemy rounds burst and sprouted from all sides. The fire came from all sides.

What at first seemed like an enemy probe, much like a fighter jabbing his opponent, had now blossomed into the beginning of a siege. One thought kept repeating itself in Harp’s mind that early Friday morning of 23 August: “These guys are really here to stay.”

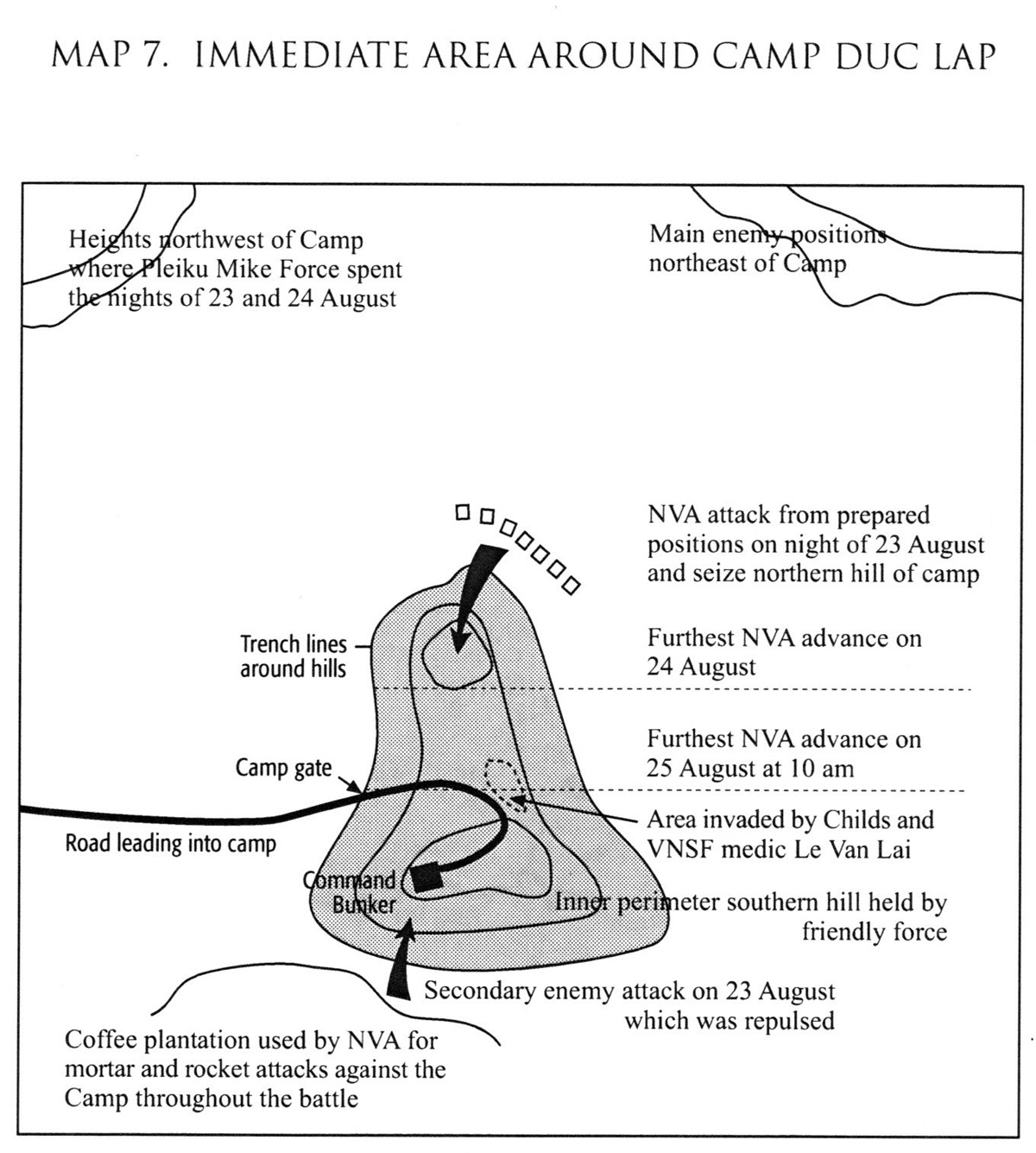

From Ban Me Thuot, Lieutenant-Colonel Ramon Reed, the “B”team commander, ordered two Companies of the Pleiku Mike Force co reinforce Duc Lap. These units landed a thousand meters north of the camp and tried to clear the enemy out of their rear support bases hidden in the jungles. (See Map 7.) Beaten back, the two companies withdrew to the heights northwest of the camp. From here they had perfect seats to watch the show as NVA units after dark slashed and clawed their way through the northern wire of the camp and seized the smaller hill. For three hours some fifty CIDG soldiers and their wives and children held out against the assaulting force of some five hundred enemy.

Fifty soldiers was all Bao and Harp could spare for the smaller hill. For the larger main hill they had less than two hundred troops. But the real difficulty stemmed from the fact that the far slope which the enemy assaulted could not be seen from anywhere on the main hill. Thus the fire from camp mortars and howitzers could not be adjusted to throw a curtain of steel death upon the attackers. Either Green Berets or VNSF could have been stationed before the battle on the small hill to perform as forward observers. Unfortunately this had not been done.

The real hero that night would be an indigenous radio man named Y-Sanh. As the enemy groped from bunker to bunker up the back slope of the northern hill, Y-Sanh and four other CIDG hid in a bunker atop the hill. Throughout the night he broadcasted back to the main hill, informing them of enemy movements and where they were emplacing weapons. All the time he requested fire right on his own position.

“He called, told us use mortars, use jets,” Captain Bao later remembered, “bomb the small hill. Even if he should die, no sweat.”

All night and into the next morning Y-Sanh’s reports flowed in, begging for air strikes, artillery, and mortars. The last message told of enemy soldiers moving into nearby bunkers, tossing in grenades and firing their AK-47’s. Then silence. Y-Sanh and his four companions were never seen or heard from again.

Saturday, like Friday, was again a beautiful day of sunshine and drifting white clouds. A perfect day for the jets! Hurling down from the heaven’s vault, they swooped in a long arc, released their bombs, and pulled upward in a twisting turn to fool the enemy gunners on the ground. The bombs, flaming napalm, or cluster bombs (a “mother unit” which spewed out dozens of baby bomblets), or simply an old-fashioned 750 pounds of explosives, the bombs—whatever kind—were not enough to blast the enemy off the northern hill. The camp, now split into a northern enemy-held half and a southern friendly portion, did not have enough strength to cast out the invaders.

After surveying the battle scene, LTC Reed ordered another company of Mike Force to join the two northwest of camp. Now a battalion strong this force marched to the camp and attempted to enter through the gate on the west. One company advised by Australians attached to 5th Special Forces managed to slip through the gate and reinforced the defenders on the main hill. But enemy fire both from the smaller hill and the surrounding fields beat back the other two Mike Force units who had to withdraw to their prior night’s position. Saturday night the NVA continued to inch forward along the trenches into the saddle between the two hills. Their goal was to pinch off the friendly hill with one arm of their force taking the left flank while the other arm took the right.

Sunday morning, the sun was rising and the sky promised another golden day. For a minute a silence filled the valley and cloaked the two dirt-red hills scarred by the battle. The world itself waited. Then a thump, a thunder, a rumbling roar as if the earth were cracking open. Again and again the ground shook. High above, so high that no sound was born, no warning, the silver B-52’s opened their bomb doors, dropped their load, and then closed their doors. Eight more times the giant planes would solemnly drop their deafening fury upon the land around Duc Lap.

The ‘’Arclights” or B-52 strikes were not an unmixed blessing, however. While the big bombers flew high overhead, all other air operations had to be called off. “’TAC air’ was on station,” one Beret pointed out later, “but it couldn’t get in because of the B-52’s.” (“TAC Air” or “tactical air” refers to the planes which provide close-in support for the ground troops when they are engaged with the enemy.) The problem was acute because the B-52 planes could not bomb within 1500 meters of the camp. The margin of error for the “ARC lights” demanded at least this 1500 meter ring in order to safeguard friendly troops. Yet this was precisely where many of the enemy were located and these were the ones who were directly assaulting the main hill. At this very time the defenders needed all the TAC air they could get.

The time was 0800. For over two hours the enemy had been pushing hard. The camp CIDG were tiring from the strain. Some of them cracked under the pressure.

“About half the Yards got up from their positions,” recalled Childs, a Green Beret defender who was in the camp’s third 81 millimeter mortar pit. “They ran back to the other side of the camp. I saw them running. So I went up to them and told these people to fucking move. I had one VNSF and one interpreter and I told them to tell these people to get their fucking asses back to the other side of the hill.”

After the Arc lights, Harp had requested TAC air strikes on the southeast side of the camp where the enemy had tried to break through earlier in the morning. Unfortunately, the napalm was dropped in the wrong place, almost on top of the defenders. Frightened, some of the indig fell back up the hill.

Alward, another American in the camp, was in the second mortar pit. He watched as three CIDG came running up the hill with no weapons.

“What the hell’s going on?” he shouted. He told the interpreter to find out. The latter asked the three terrified men.

“Beaucoup VC come,” he translated. “They quit. Drop weapons. Run.”

Alward relayed this to Harp and Boody in the camp tactical operations center (TOC).

“Get those people back into position,” Boody said.

But these three men were like the break in the dam. All the CIDG seemed to be leaving their positions in the lower perimeter and flowing toward the top of the hill. They all wanted to be where the Americans were.

“Yards from the other side to the south down by the motor pool and plantation were flooding up the hill.” (See Map 7) Childs went on. “They broke through our barbed wire. I fired several rounds over their heads but they just weren’t going to stop. They wanted in our compound. I could do nothing about it. They flooded up, dependents and all. So I took these people and had them situated around the area. I started pushing a large majority of the Yards back towards the northeast section of the camp where the main ground attack had occurred and where the next one would probably come.”

“This was really scary,” Boody said afterward. “This was the one point where we thought possibly Charlie was on the hill and that we had had it.

“It meant our asses if we didn’t get these people back in positions,” Alward remembered later. “We threatened and pushed them.” Everybody—Americans, Australians, and VNSF—were yelling and shoving the Montagnards to go back.

“I grabbed this one guy,” Alward continued, “he had been in the second 81 pit. He could get along in broken English. I said, ‘You get those damn people back into those trenches or we’re dead!’ I pushed him toward them. Then I walked toward clusters of CIDG, threw out my arms, and said, ‘Get back, get back into those positions.’ It seemed we were being overrun by the CIDG. They brought all their families with them. There’s nothing you can do when a Montagnard is with his family. That’s his one concern. So we said let them get their families into the bunkers and pits. Then we hustled their asses out. All of us Americans were out there, physically pushing them, grabbing them, shaking our rifles in their noses, making them go back to their positions. They finally did, not as well as before, but at least we had a real tight perimeter at the top of the hill. At that time this was the only ground the friendlies held. We just sat tight then. That’s all we could do. We went back to the mortar pits and constantly watched that these people didn’t break again.”

Shepherd, the ‘’A”-team medic, tried out a different technique on the scared CIDG. “I watched the little kids clinging to their parents. The older ones were carrying ammo cans filled with water or clutching sacks of clothing. They all look frightened, so I began laughing at them. I tried to make little jokes to stop their panic. Some would smile at me, but others must have thought I was crazy.”

Wast, an American with the Mike Force company which had entered the camp on Saturday, was yelling and pushing the CIDG back. All the time he was wondering how would the newspapers back home write this up.

“The civilians had started coming up first,” Smith, an Australian with the Mike Force, described his experience that morning, “droves on the run, crying and screaming, the troops following them. We got them back here they belonged; but for half an hour things looked pretty grim. I just patted them on their behinds, pointed the way back, and shot some M-16 ammunition off. They just realized there was nothing else to do.”

Some of the Mike Force company, despite their elite training, had also left their positions and followed the Camp Strikers up the hill. Their company commander, named Toget, who Saturday afternoon had kicked and shoved his men through the gate into camp, now ran toward his soldiers, yelling and swearing at them. He grabbed a couple and punched them, then thrust them back toward the trenches.

“The company commander did a good job,” Smith declared. “He wasn’t as polite as we were, but he got them back where they should be.”

Commander of a Nha Trang “Mike Force” Company and his USASF Advisor

“I was scared myself during this time,” declared Hall, a member of the “A” team at Duc Lap. “My shit was really weak. I was saying my prayers because I thought it was all over. We had to make a tight perimeter and hold it. This seemed like the last stand. Reinforcements were supposed to on their way, but they seemed too distant to help.”

Childs made sure that the perimeter was re-established on the northern slope.

“They were rather slow moving back,” Childs said. “Half of them had run from this area before and they weren’t too swift about getting back. Nobody wanted to get out of the trenches at the top of the hill and move. We were under fire, though somewhat sporadic. It was urgent to get these people spread out because we didn’t know when the attack was coming. I had the interpreter and a VNSF soldier helping me. Finally we got them spaced out, one Yard every five or six feet.

“After making sure everybody had ammunition, I walked back toward the TOC and had all the dependents get into two or three bunkers with orders to stay there. Many didn’t want to leave their husbands, but I forced them to. Returning to the perimeter, I told everyone through the interpreter and the VNSF that if they ran I was going to kill them. If they deserted, the whole place would fall. So everything depended on them. If they didn’t want to be killed by me, they’d stay where they were.

“I was determined I would shoot these people if they ran because I knew Charlie would have to come through this way. I was also wishing for more grenades. I felt that the Yards would not hold this position through the following night even though it meant their own lives. If the enemy attacked, they would overrun the main hill in short order. All this time I half expected a bullet in my back from someone. We had information there were Charlies who had infiltrated our Camp Strike Force. I even thought a friendly might shoot me because I know I wouldn’t like someone shouting at me and threatening, ‘I’m going to shoot you.’ I can remember one goofy thought in my mind that if Charlie got through it would be over my dead body.”

Although the perimeter was intact, the camp continued to receive a lot of B-40 rockets and mortars. Most of this seemed to be coming from a “friendly” village. This continuous fire menaced the shakened morale of the CIDG. About 0900 hours the camp requested an air strike.

“The strike sure got results fast,” related Smith. “The first two runs dropped cluster bomb units. About twenty-five NVA began to run from the village. An F-100 swooped down and unloaded napalm right in the middle of them. Really a good sight. The Yards were very pleased to see that, smiling and jabbering. Things looked bright again. The napalm would hit a hut where the enemy was hiding and the hut would just disappear into a beautiful yellow-orange mushroom of flame and smoke.”

Thus ended one crucial episode in the battle for Duc Lap. Unlike Camp Ashau in 1966 when the pull back of the indigenous soldiers turned into a rout and Americans actually had to shoot friendly troops who had gone berserk, at Duc Lap on that Sunday morning the Green Berets, Aussies, and their Vietnamese counterparts had rallied their soldiers to hold and fight back.

Leave A Comment