Gunship Pilot with MACV-SOG Special Forces Teams into Laos

1967, the 119th preparing to insert MACV-SOG hatchet force (Photo by Stephen Pettit, Juliaetta ID)

By Gordon Denniston

Originally published in the April 2015 issue of the Sentinel

During the Vietnam War, the U.S. Special Forces and helicopter crews assigned to Military Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group (MACV-SOG) engaged the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) along the Ho Chi Minh Trail in the famous “secret war in Laos.” The “trail” was the principal supply line used by the NVA to move men, arms and supplies from the Communist North into South Vietnam.

As we know, this “trail” was actually a massive network of roads, camps and storage areas. Cross-border MACV-SOG Special Forces reconnaissance missions were tasked to identify the exact locations of the NVA roads, troop movement, and facilities. Other MACV-SOG missions in Laos had a different objective… they aimed to directly engage the NVA in their own territory.

Ho Chi Minh road and bomb craters (Photo by Gordon Denniston, Daphne AL)

Generally, each of the three MACV-SOG units (Command and Control [C&C] North, C&C Central, and C&C South) were headquartered at a “Forward Operating Base” or FOB, and had three ground components. The reconnaissance teams (RTs or Spike Teams) were usually composed of two or three USSF with 6-12 indigenous troops, usually Montagnards from various tribes. The “Hatchet force” was platoon-sized, usually three USSF with 20-30 indigenous troops. They were intended to be a reaction force to help rescue RTs that were in trouble. But, they were also used to engage in other direct combat actions.

Finally, each FOB had one to four company-sized units that were referred to as “SLAM” or “Hornet force.” These men were recruited mostly from Montagnard tribes and were directly commanded by Special Forces MACV-SOG men. In this respect, MACV-SOG differed from other Special Forces units such as Mike Force or the A-Team Striker companies. In those units, Special Forces troopers were nominally “advisors,” though in practice USSF usually commanded while in the field. These Hatchet and Hornet force units gave the FOBs a punch for cross-border opportunities.

MACV-SOG operations were largely declassified a few years ago [in the early 1990s]. Indeed the unit was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation in 2001 in a ceremony at Fort Bragg that was well attended by survivors. Many of the MACV-SOG missions have now been publicized and much is now known of the Special Forces men who staffed that organization. Members of MACV-SOG were awarded nine Congressional Medals of Honor and twenty-three Distinguished Service Cross medals.

What is less well known is that the air assets of MACV-SOG were not ad hoc, but were definitively attached to the FOB and at least one of those CMHs was awarded to a helicopter pilot. Gunship and “slick” pilots were based with the Special Forces MACV-SOG troopers. They lived with them, ate with them, and spent nights at the same bar. They were an essential part of the mission planning and debrief sessions, and today the surviving pilots/air crews are welcomed at the Special Forces Association meetings, and many are members of the SOA.

The contributions and organization of the air assets of MACV-SOG has not been widely discussed. Indeed, some SOG Special Forces troopers from Vietnam may not even have been aware that the attached air unit was their direct asset for inserting, protecting and extracting the teams sent cross border.

In II Corp, the principal base for MACV-SOG was at FOB-2 in Kontum, re-named late 1967 as “Command and Control Central” (CCC).

The launch site and mission control for cross-border missions was from the airfield at A-244, the Special Forces Camp located at Dak To. That airfield had the field C&C (command and control) base for SOG.

Gunship over MACV-SOG base FOB-2, Kontum, 1967 (Photo by Lloyd Adams, Athens AL)

During the early days of SOG missions most of the Special Forces teams were transported into the enemy area and out again by H-34 helicopters piloted by highly skilled and courageous Vietnamese pilots. Alternatively, on occasion U.S. Air Force helicopters were used for these missions. Later, company sized U.S. Army helicopter units were directly assigned to MACV-SOG.

From the creation of MACV-SOG in 1964, U.S. Army gunships were the principal aerial fire support during insertions and extractions. Backing up the gunship support for the teams, the Air Force provided close air support (CAS) assets for bombing and strafing with A-1E propeller aircraft and jets. The forward air controllers in light planes scouted the area, spotted targets, and coordinated the air support. Over the Ho Chi Minh trail, the volume of NVA anti-aircraft fire was always intense so flying a slow aircraft or helicopter required new tactics and some luck.

In November, 1965, our Helicopter Company, the 119th Aviation Company (also called Assault Helicopter Company or AHC), was organized under TO&E1-77G. The 119th was operational under the 52nd Combat Aviation Battalion, 17th Combat Aviation Group, 1st Aviation Brigade, headquartered at Camp Holloway near the town of Pleiku.

Camp Holloway, Pleiku (Photo by Stephen Pettit, Juliaetta, ID)

The 119th consisted of a Company Headquarters, two Airlift (slicks) Platoons, one Armed Escort (gun) Platoon, a Service Platoon, and other support detachments. The 119th operated and maintained a total of 21 UH-1D (slick) helicopters. These assets were informally known as “the Alligators,” or “Gators.”

There were also 8 UH-1C (gunship) helicopters, known as “the Crocodiles,” or “Crocs,” see informal unit patch above. In 1966, the Gators and Crocs were assigned to Special Forces in support of MACV-SOGs operations out of FOB-2.

I arrived in Vietnam on November 11, 1966 and was assigned to the 119th on the same day three Army gunships were shot down near the Cambodian border west of Special Forces camp A-251, Plei Djereng.

See action report: Colonel (Ret.) Phil Courts Report: http://www.vhpa.org/stories/Shootout.pdf

119th Gary Rogers, H-34 slicks, Viet crew, excellent men (Photo courtesy Gary Rogers, Houston TX)

I soon discovered that I was a replacement for these losses. For my first 6 months in Vietnam, I flew a UH-1C gunship on “normal” missions. During these months, I learned the finer points of tactics and developed skills and accuracy which were essential for survival. Most of the time, I flew the same aircraft and had the same crew members so as a team we became very proficient and accurate.

Life in Pleiku flying “normal” missions changed suddenly when we were instructed to pack our gear and fly to Kontum where I would be briefed after landing. No one in my unit knew where we were going or when we were returning. We were only told that “you are to going to fly for MACV-SOG.”

We quickly discovered that while the “normal” missions in Vietnam could get you killed, flying in Laos was LIKELY to get you killed. I had never experienced the volume and intensity of ground fire in Vietnam that we faced on most missions in Laos. We had gunship tactics that minimized the enemy’s ability to shoot you down, but in Laos we quickly discovered that we needed both discipline and some innovative tactics to nullify their defenses if we were to survive.

“Crocodile 3,” Gordon Denniston and crew, 1967 (Photo courtesy Gordon Denniston, Daphne AL)

We had the TEN RULES of the gunship pilot that included simple but logical things such as “don’t fly over the same place twice” or “only fly at tree top level or at very high altitude.” From tree top level to altitude was referred to as “the dead man zone.” In my opinion, it is important to note that modern day special operations core strategies directly evolved from the tactics that were first developed supporting these MACV-SOG Special Forces teams going into Laos. Those missions were flown into an enemy area garrisoned by an abundance of NVA troops that were equipped with everything from AK-47’s and RPG’s to 12.7mm and 37mm antiaircraft guns.

My job as a gunship pilot was to protect the “slicks,” troop carrier helicopters going in to insert or extract the MACV-SOG teams. We often inserted the teams into bomb craters, open fields, or on the actual trail. The insertion and extraction points were frequently the most dangerous moments of a MACV-SOG mission. These points were always the subject of considerable planning by team members and air assets.

The NVA frequently set up gun emplacements covering the relatively few likely landing areas. Then they would try to ambush the slicks as they were landing. If the insertion helicopters started receiving fire, the gunships would attempt to suppress that fire. If the landing zone (LZ) turned hot, the mission was aborted and we would paste that area hard with gunships, A-1E’s and jets, and those Air Force lads would get “up close and personal.” (Sidenote: A lengthy “john-wall graffiti” poem in FOB-2, “Ode to the Skyraider,” had these lines … “Dawn of the day you could see them arrive; With nape on their wings and blood in their eye…”)

A-1E Skyraider in close air support (Photo courtesy Gordon Denniston)

Usually the NVA would wait until the MACV-SOG team was off loaded before they started shooting. Once a team was surrounded and under NVA fire the extractions became much more dangerous.

The H-34’s would be a sitting target while they were trying to on-load the team and many times we lost a slick and were then faced with extracting both the team and the aircrew.

This would start an indescribable spectacle involving flights of helicopters and airplanes all over the sky trying to get our people out. I recall one mission where I was going in on a gun run and an A-1E was diving down out of the clouds to drop bombs on the enemy. We almost had a mid-air collision. The A-1E went over my head and the bombs went under me with one hell of an explosion just to the right side of my aircraft.

In the air we were always in danger, but in truth, the biggest threats were faced on the ground by the Special Forces teams that were often inserted into the center of NVA battalion size units. The small “Spike teams,” usually two-three Americans and six-twelve indigenous troops, were the core function of MACV-SOG and we worked hard for them. But despite their extreme professionalism and bravery, casualties were high.

When we flew support of the Hatchet force teams of several Americans and about thirty indigenous troops, we were sometimes lucky to get the two-three USSF Americans out, and on occasion we lost most or all of the indigenous members of the team. Sometimes a Hatchet force would be inserted as bait. They would engage an NVA battalion size unit of several hundred men who would then become targets for stacked air support, gunships, A-1E Skyraiders, F-100s, and even on occasion, B-52s (!).

Spike team loading up on 119th slicks, FOB-2, Kontum, 1967 (Photo by Gordon Denniston, Daphne AL)

At the end of these attritional type battles we usually counted several hundred NVA killed. It was not uncommon for these Hatchet Force teams to successfully take on a ratio of ten NVA to one. It was also not uncommon to insert a team and never hear from them again. Many Special Forces RT team members were wounded multiple times, and the KIA rates were very high. Our losses from the air assets were not on a par with the troops on the ground but were also heavy. Twenty-five percent of my flight class was killed during the first year we were in Vietnam and the 119th lost over 60 pilots and crew members during their Vietnam deployment.

Although there were bad missions where we lost teams or extracted them with too many killed or wounded, there were occasionally good missions. Here is the story of one of the good missions which involved the insertion of a RT team into a concentrated area of activity.

The team made it in okay and started their search for the headquarters of a NVA regiment in the tri-border area. They searched for several days before they found an unbelievable sight. The NVA had set up office buildings, parade ground, storage buildings, and communications buildings under heavy camouflage that were not visible from the sky.

When I got the call to fly out to their area it was mid-afternoon. We lifted off with our gunships and on the way I had a FM radio conversation with the team leader. He described the situation and said his team was hiding in the bushes very near the buildings. His plan was to just walk into the headquarters building and shoot up the place. He said his team was then going to run down the trail next to the river until they arrived at a sand bar about half a mile away in the middle of the river where the slicks could pick up the team. They had studied the area and planted claymore mines along the trail to cover their escape.

I was dumbfounded when I heard the plan. Who on earth would think this was a good idea? I knew his exact location by homing in on his FM radio. So I told him to let me know when he was ready and I briefed the other gunship. Our plan was to fly in from the direction of the sand bar toward his location and provide fire support during his escape. We could clearly see the trail by the river.

I got the call from the Special Forces leader on the ground that they were ready to attack so I rolled in toward his location. I can only summarize from the after-action briefing. Dressed like indigenous, they simply strolled into the front door of the NVA building and opened up on the NVA general and his staff. They must have killed more than fifteen NVA in a matter of seconds. They then walked calmly out of the building shooting up and killing everything in sight. After that, they made a mad dash for the sand bar.

Rocket impact from gunship, 119th, 1967 (Photo by Stephen Pettit, Juliaetta ID)

When I flew in at low level, I could see our team running down the trail toward the river. My GOD!! The trail behind him looked like a riot was in progress. There must have been over one hundred NVA chasing the team. The amazing thing about what I saw was that the NVA soldiers were not shooting at our team. They apparently intended to run the team down and capture, interrogate and then kill them. The NVA considered our SOG men as terrorists so they didn’t often take prisoners.

I assure you that when a gunship pilot sees hundreds of enemy troops running after Americans in the open it is a dream come true. The Gatling guns on my aircraft could fire 4,800 rounds per minute, and I had 14 rockets with high explosive heads. Behind me was another gunship with the same firepower. This does not include the firepower of the door gunners who each had about 2,000 rounds.

Our first run rolling in over the fleeing RT was successful with many NVA downed, and then we came around for the second run, mini-guns screaming, rockets flying. Meanwhile the team was running for their lives but the numbers of chasing NVA we could see had been significantly diminished from casualties and others who had apparently just become terrified.

My second gun run was quite unnerving since the team set off a claymore mine just as I was banking in over the area. My first thought was that my aircraft had blown up, and I was going to crash into the hands of the enemy. But by some miracle we kept flying and continued to lay down fire support.

Gunship rocket sight (Photo by Stephen Pettit, Juliaetta ID)

The Special Forces RT team made it down the trail next to the river and waded across to the sand bar. They were then neatly picked up by a slick. We had expended all of our ammunition so it was time to go home. As soon as we cleared the Air Force took over and wrecked the entire area. At the end of the day we knew we had delivered a serious blow to the enemy and better, every man made it home without a scratch to celebrate with us at the bar that night.

From my pilot’s seat, I controlled the aircraft and my co-pilot fired the mini-guns. As right seat, I fired the 2.75-in rockets (see rocket sight, Figure 10, page 7). We got to be pretty good shots with those rockets and I wouldn’t have wanted to face a gunship rocket barrage on the ground. At a distance of about a mile I could hit a 55-gallon oil drum. We were very accurate.

At 4,800 rounds per minute the mini-guns could saturate a target. On our gunships we had two, one mounted on either side, controlled by the co-pilot. Additionally, my door gunners played an important role with their M-60 machineguns that fired 7.62mm. These men were deadly accurate and provided protection to the side and rear of the aircraft.

Gunship mini-gun (Photos courtesy Gordon Denniston, Daphne AL)

In the photos above, top-left: loading the ammunition trays for the mini-guns. Top-right: Air Force helicopter gunship supporting us, with a mini-gun mounted in the door. Bottom right: mini-gun firing to the right. When the left gun hit the stop, the right gun would point further to the right and the gun would increase the rate of fire from 2,400 rounds a minute to 4,000 rounds per minute.

View through mini-gin sights, outgoing tracers during strafing run over the Ho Chi Minh Trail (Photo by Gordon Denniston, Daphne AL)

Aerial view of portion of Ho Chi Minh Trail from Croc 3 (Photo by Gordon Denniston, Daphne AL)

In 1967, we occasionally did some things only young pilots would do. One such thing was a balancing act, taking pictures with my 8mm movie camera while flying in action. I don’t recommend the practice today, but the two photos above I extracted from 8mm file taken while on combat missions over the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

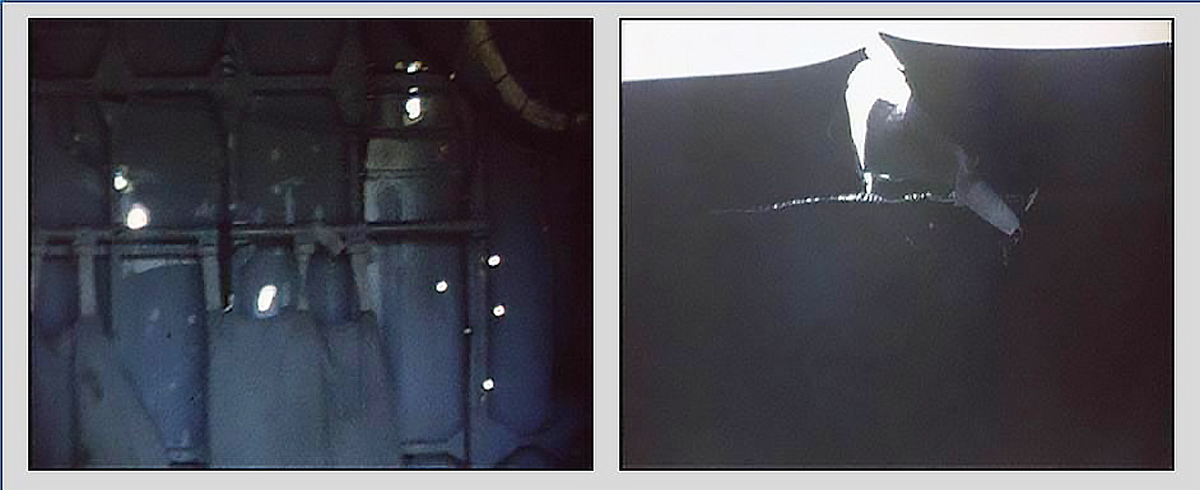

Left, damaged H-34. R-119th “croc” gunship after mission (Photo by Gordon Denniston, Daphne AL)

In the photo above, on the left, is an inside view of a Vietnamese H-34 that had about one hundred bullet holes in the aircraft but made it home. Several men were killed in this aircraft. This was a mission that went bad when the NVA ambushed the aircraft on landing.

The photo on the right shows the rotor blade belonging to a 119th UH-1C gunship flown by WO Gary Rodgers when he received heavy anti-aircraft fire flying over the trail. He was lucky he survived. If his rotor blade had broken, we would have lost the entire crew.

As gunship pilots we had the responsibility to defend the slicks and the men on the ground. We also flew missions actively searching for enemy positions and would engage the enemy usually with great effect. But of all the missions that I flew during the war, the most challenging and worthwhile were the ones with the Special Forces MACV-SOG people.

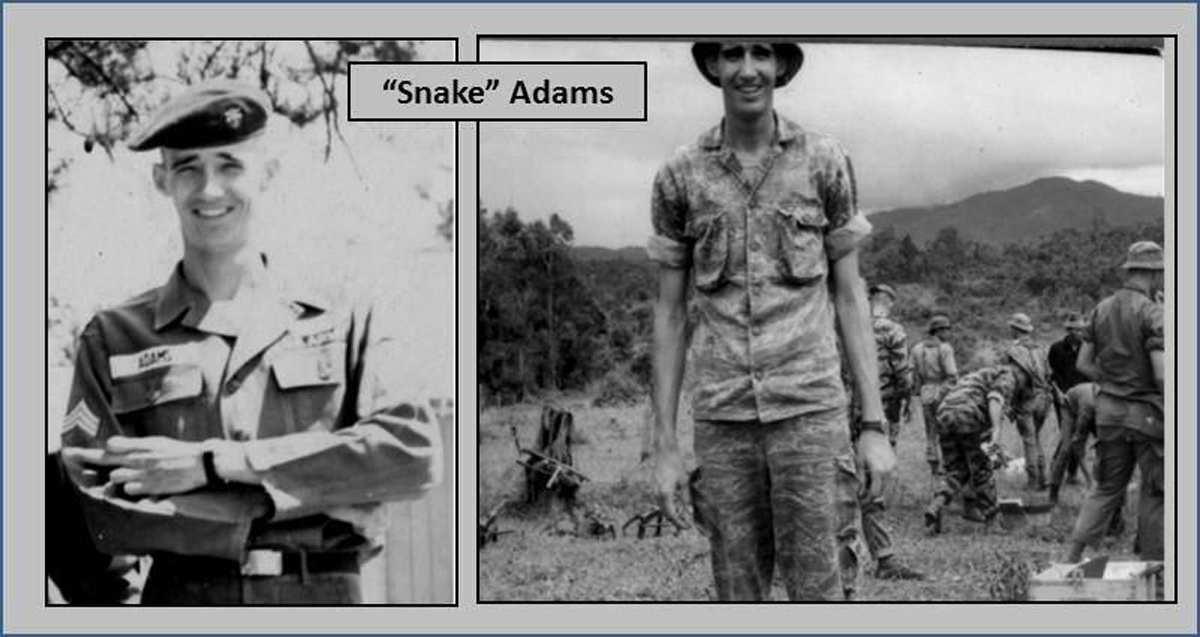

Three of the Special Forces men that come to mind with their respective call signs are: Jerry Shriver (Mad Dog), Lloyd Adams (Snake), and Robert Sprouse (Squirrel). These men deserve to be remembered today.

Photo courtesy Gordon Denniston

Jerry (Mad Dog) Shriver was a MACV-SOG and Special Forces legend who was KIA’d 24 April 1969. I provided gun cover for his team on several missions. He kept running missions for over two years until the day he was killed. There were several evenings in the bar when Jerry and I discussed tactics. I wanted to understand his tactics and he was interested in ours.

Read more about Jeff Shriver. [see editor’s note below.]

Photo courtesy Lloyd Adams, Athens AL

Lloyd (Snake) Adams another legend of MACV-SOG, ran countless missions in Laos. He often told me that if you had any chance of surviving you better be a distance runner. The NVA was constantly searching for the teams even, using dogs. When they got on your trail you had better outrun them unless you had a good ambush set up. Lloyd is still with us (amazingly) and he shared his collection of personal photos with me several years ago, some of which are used here.

Squirrel Sprouse (Photo courtesy Lloyd Adams, Athens AL)

Robert Sprouse (Squirrel) was also a true professional and role model Special Forces MACV-SOG RT 1-0. Here is a quote about him from John Plaster’s book: [discussing why the same RT teams were deployed over and over]

“Afterward, walking from the Tactical Operations Center, I asked Ben, “Why RT Illinois?”

The answer was obvious to him. “Look around. How many teams we got combat ready, right now?” Since January 1 our little sixty-man recon company had suffered six Americans killed, and another twenty-two Green Berets wounded — meaning, in three months almost half our U.S. personnel had become casualties. As a result, the eight or so green teams — those teams up and ready — carried a disproportionate mission load, going out again and again, even though our manning board listed about twenty teams. But why put us back in the same target? … “Military logic,” George offered. “The staffers ask themselves, ‘Who knows the area best?’ And the answer is, ‘The guys that just came out of there.’”

“Recon men didn’t appreciate that logic. “Bein’ run to death” is what RT Wyoming One-Zero Squirrel Sprouse called it, being inserted over and over into the same area, using every tactic and trick you could devise until, eventually, you defied the odds once too often and paid a terrible price. …the better the One–Zero, the better the team, the more likely you’d be run to death.”

I finished my tour with the 119th in support of MACV-SOG in November, 1967. I returned for a second tour in 1969, though it did not involve MACV-SOG. Today, I have immeasurable respect for the Special Forces troopers who geared up day after day to challenge the communists on their own trail in Laos and Cambodia. As a member of the “Crocodiles,” we lived, planned, launched, fought and partied with MACV-SOG Special Forces from FOB-2. I am proud to have played a part in the missions of these legendary troopers.

Editor’s Note: Gordon hopes to have his book “Mad Dog” Shriver — His Covert War Against the Communists In Southeast Asia in print in time for the 2023 Special Operations Association Reunion (SOAR XLVII) in October. Paper shortages and other delays over the last couple of years have slowed down progress, but it will be the most comprehensive book about Jerry Shriver ever written. It currently is 700 pages long, with over 400 photos and 50 maps. Stay tuned for news regarding its availability.

WO Gordon Denniston, “Crocodile 3” 119th AHC, 1967 (Photo courtesy Gordon Denniston, Daphne AL)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR — Gordon Denniston served with the 119th in 1966 and 1967. He returned to Vietnam for a second tour in 1969 and was assigned as General Stillwell’s command pilot. Upon DEROS and ETS, he finished his education at the University of Alabama graduating in 1973.

In 1975 he became an instructor, pilot, and test pilot for Bell Helicopter under contract to the Shah’s Monarchy of Iran. Escaping Iran (under “extreme” circumstances) after the Ayatollah’s revolution, he returned to the U.S. where he became Director of Quality Control for Fairchild Republic, on the build of the A-10 in New York.

From 1984–1993 Gordon was Director of Quality Control for Avco/Textron in Nashville charged with building the wings for the B-1 and C-5. Since 1993, he has run his own company providing project management services in technology and hospital revenue cycle operations for a number of large hospital corporations.

Very interesting, as a gunner assigned to the 119th, Croc’s 68-69, This article was informative / interesting. Welcome home.

thank you, this helped to clarify what we were doing during the SOG. missions of 1967. welcome home.

Nice recap Gordon

Dube

Any chance one of you remembers a mission where a Gunship was shot down by a possible SAM while covering a Dustoff the door gunner being the only survivor? My former boss said he’d been a door gunner and shot after extending to get out of the infantry with the 101st. Time period would be 67/68

Love talkin to gordon. He is just a wealth of knowledge , i learn something every time we talk.

Ill talk to him let him know come and see these replies

Could it have been a UH-1C gunship flown by R Hewitt (119th AHC) in the vicinity of Hill 875, Nov ’67. He survived the shoot down, but succumbed to massive burns on Medivac Flt home to Ft Sam (burn center).

love talking to gordon, Hes such a wealth of knowledge, i learn something every time we talk