FALLEN SOLDIER

Colonel James “Nick” Rowe

Colonel James “Nick” Rowe

Part 1 — The Man in the Arena

By Greg Walker (ret), Special Forces

Far too many U.S. military officers have been the targets of assassination over the last several decades. But few have attracted attention like the murder of Colonel James “Nick” Rowe. Rowe had accepted an assignment that many of his close friends felt was too dangerous for the former POW to consider, much less embrace as an overseas posting.

James “Nikki” Rowe was born in McAllen, Texas. He was one of three children although both his sister, Mary Alice, and elder brother, Richard, died at early ages from natural causes. It was Richard’s death during his last year at West Point that had the most profound effect on six-year old Nikki, who during the military funeral in McAllen told his grieving mother, “I’m not going to die. I’m going to do the things my brother wanted to do and never had the chance.”

Rowe graduated from West Point in 1960 as a second lieutenant in field artillery. Already a graduate of the Army Airborne and Ranger courses, Lt. Rowe went on to attend the field artillery Officers Basic Course at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. It was there Rowe became aware of a unit called Special Forces. “A recruiting team asked for volunteers to go to Special Forces,” recalls Susan Rowe, Nick’s second wife. “Nick was one of the six who were chosen out of all those who volunteered. He was always interested in doing something new, and the Green Berets were definitely new at that time.”

Nick Rowe as a West Point cadet in 1957. (Photo courtesy Greg Walker)

First sent to the Defense Language School in Monterey, California, Rowe studied Mandarin Chinese. While at DLI he was promoted to 1st Lieutenant. Finally arriving at Fort Bragg, where no Special Forces Officer Course had yet been developed, Rowe attended the Enlisted Special Forces Qualification Course. After graduation, he attended HALO school. In 1962 he served as assistant Group adjutant at the 7th Special Forces Group (ABN), then as an executive officer on a Special Forces A-team in 5th Group (A-23).

Special Forces operations were still in a stage of relative infancy when Rowe’s 5th Group detachment was deployed to Vietnam in 1963. American advisers could not call on U.S. jet and artillery support in the manner they would be able to by 1966. Nor could they count on American conventional force combat units to come to their aid when their isolated A-camps were attacked.

Sent to a remote camp 16 miles inside the Viet Cong controlled Mekong Delta, it was A-23’s responsibility to work with and train their Vietnamese Special Forces counterparts, the LLDB, in combat operations against the entrenched Viet Cong. Three months after landing at Tan Phu, Nick Rowe was captured along with Captain Humbert “Rocky” Versace and Special Forces medic, Sergeant Dan Pitzer. Their capture, on October 23, 1963, occurred after an intense firefight outside the wire at Tan Phu.

“I believe the VC knew we were with Special Forces within several days of our capture,” recalled Dan Pitzer. Rocky, Nick and I were picked up along with several LLDB people. There’s no doubt in my mind they told the VC who and what we were. But Special Forces, or SF, was so new to them [the Viet Cong] that it just didn’t mean that much at the time. Dan Pitzer would spend four years as a POW along side Rowe in the U Minh Forest (“Forest of Darkness”). Pitzer, who would later join Rowe at the newly formed U.S. Army Survival, Escape, Resistance, Evasion (SERE) school at Fort Bragg, came to know Nick better than anyone.

“We got closer than brothers do during that time,” Pitzer told me. “POWs come to rely on each other for everything, and in doing so they exchange things about themselves that no one else would ever hear about. When I went to visit Nick’s parents after my release in 1968, I didn’t need a map of McAllen or anyone’s instructions on how to get around. Nick had told me everything about McAllen, it was as if it was my hometown, too.”

During his five years as a POW, Rowe fought to sustain not only his own life and sanity but that of his fellow POWs, as well. Pitzer served to gauge each prisoner’s mental and physical health, advising the young lieutenant as POWs rotated in and out of the jungle camp. Rocky Versace, fighting the VC’s attempts to force him to betray his country to the bitter end, was finally executed along with “Green Beret” Ken Roraback (pictured at left) on September 25, 1965. Upon hearing of the executions Rowe began his own war against those holding him, supporting it with a cover story that did not mention his Special Forces background.

Special Forces Sergeant Ken Roraback was executed by the Viet Cong in the same camp Nick Rowe was being held.

On December 31, 1968, after five years of imprisonment, his last year spent in total isolation, Nick Rowe made his fourth attempt at escape. He was successful. He later recounted that the circumstances leading up to his rescue began with the revelation that he was indeed a Special Forces officer. The tip came from U.S. anti war protesters with ties to the North Vietnamese. When his true identity was learned of, a set of orders came down mandating he be turned over to a higher cadre than the regional level which he’d been held at until then. “At Zone there was no pretense of leniency and humanitarianism,” he wrote in his autobiography. “There was a harsh, unyielding process of deliberately breaking a man. If a prisoner still refused to comply, it became tantamount to ordering his own execution.”

On the day of his rescue, Rowe was being moved toward a transfer point by his Viet Cong guards. He was sure he was to be executed since he had no intention of caving in, although there was no execution order. Dan Pitzer supported Rowe’s belief in this assumption. “After Rocky’s execution we were told that it was not the policy of the Front to kill prisoners. Versace and Roraback were killed in retaliation for several VC killed in Danang. What they did tell us was they didn’t have to ever let us go. That they could keep us forever.”

A surprise air strike gave Rowe his chance at freedom. He disabled the single guard assigned to move him and managed to signal an attacking gunship using his now-bleached white mosquito netting. Still, almost “lit up” because he was wearing black pajamas, he became the object of the Airborne Commander’s wishes to capture a live VC. Minutes later Nick Rowe was high above the Forest of Darkness, his promotion to major and a ticket back to the United States less than 20 minutes away.

Once on the ground, Rowe debriefed a combined force of Vietnamese Rangers and American advisers. He volunteered to fly back to the area he’d been held for five long years in, this to assist a combined assault force hoping to locate other POWs or recover any information about them that would help with future rescue operations.

Much later Rowe recalled it wasn’t until he’d climbed into the Army jeep after his rescue that he realized with certainty he was finally a free man once again. He would tell those SERE students going through the course he was responsible for that in his role as a U.S. Army officer, “The minute I put this uniform on, it says I am expendable.”

Rowe recalled that it was not until he climbed into the Army jeep after his rescue that he realized he was finally free from his jungle prison.

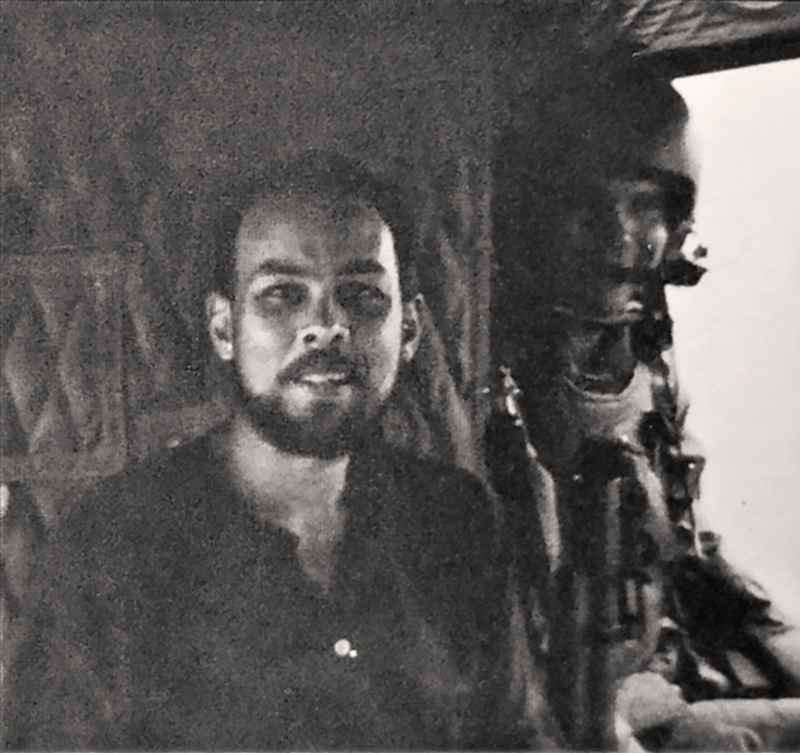

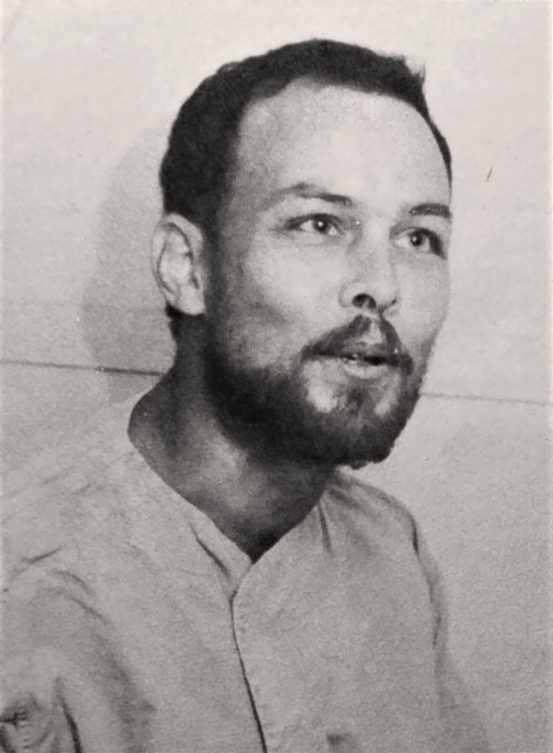

Rowe during his first medical exam after his escape.

Once back home in Texas, now Major Rowe told a throng of reporters “I have already asked to be sent back to Vietnam. I feel the experience I have gained over the past five years will be very beneficial. I have gained a wealth of knowledge I could never have gained in any other manner.”

Rowe’s request was denied. Instead, he found himself assigned to the Army General Staff Office of the Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence. He later worked on the Army’s POW/MIA program. In 1974, he resigned his commission and ran for state office in Texas. He was badly beaten. Afterward, Susan recalled, he decided politics were not for him. Heavily in campaign debt, Rowe returned to a steadier form of income than his writing could provide. Affiliated with the 20th Special Forces Group (ABN), Rowe had been working occasionally as a consultant, lending his expertise and quick mind to a variety of projects. As U.S. special operations began to shift gears in 1981, he returned to active duty to develop a program for personnel who might be captured during the conduct of their missions.

Rowe’s unique experiences, dynamic personality, and unshakable commitment to serve where his country most needed him now fit in perfectly with the Army’s desire to reevaluate its position on survival, escape, resistance, and evasion, or SERE. He soon became a constant presence at Camp Mackall, the secluded and rough Special Forces training center that would come to host his SERE program.

After his arrival and hands-on effort to begin turning the tide against Communist revolutionaries seeking to topple the government of President Cory Aquino. On April 7, 1989, Colonel Nick Rowe wrote the following in a letter to Dan Pitzer. “I’m either Number 1 or Number 2 on their list at JUSMAG and have taken the actions available to me to make it more difficult for them…Their targeting instructions are for an officer, involved in the counter-insurgency effort. DAO and JUSMAG are ground zero. It is many things here, but not dull.”

On April 21, 1989, Nick Rowe died at the hands of the Communist New People’s Army. The story of his assassination to be presented in the May issue of the Sentinel in “Part II – Death in Quezon City.”

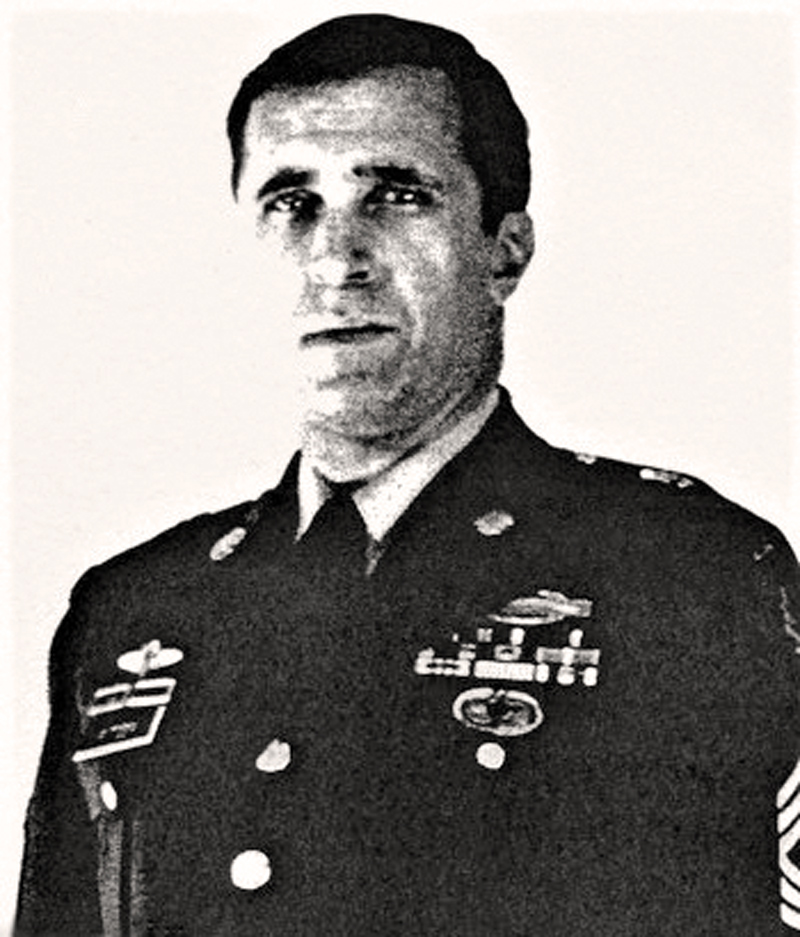

About Command Sgt. Maj. Daniel L. Pitzer

Dan Pitzer was born on November 23, 1930, in Fairview, West Virginia. He enlisted in the U.S. Army on December 10, 1947, leaving active duty on June 22, 1949, and then returned to active duty from November 6, 1949 to September 10, 1950.

He was again recalled to active duty on August 22, 1951, and served with the 2nd Medium Tank Battalion of the 1st Cavalry Division in Japan and South Korea until November 1960, followed by service with the 319th Artillery Regiment at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, from January to June 1961.

Command Sgt. Maj. Daniel L. Pitzer

Sgt Pitzer next completed Special Forces training, and then served with the 5th Special Forces Group at Fort Bragg from December 1961 to August 1963. He was then deployed to South Vietnam from August 1963, until he was captured by Viet Cong forces and taken as a Prisoner of War on October 29, 1963.

After spending 1,475 days in captivity in South Vietnam and Cambodia, MSG Pitzer was released on November 11, 1967. He was briefly hospitalized to recover from his injuries at Fort Bragg, and then served with the 6th Special Forces Group at Fort Bragg from June 1968 to March 1971.

His final assignment was with the 5th Special Forces Group at Fort Bragg from March 1971 until his retirement from the Army on June 19, 1975.

Dan Pitzer died on March 9, 1995, and was buried at Lafayette Memorial Park in Fayetteville, North Carolina.

Alfred Clark “Al” Mar was born in the United States. He was the son of Chinese immigrants. Al served in the 11th Special Forces Group (ABN). In the late 1950s, Sergeant Mar volunteered to serve in Vietnam with a special project using all-Asian Special Forces soldiers. The project was run out of Okinawa where the 1st Special Forces Group (ABN) had a forward deployed battalion. After serving in the Army, Mar earned a master’s degree in industrial design from the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, California. His masters thesis was building and launching a working 2-man submarine. Upon graduating he went to work for an industrial design firm in Los Angeles in 1967, and upon moving to Lake Oswego, Oregon, he joined Gerber Legendary Knives as a designer. Mar was responsible for a number of innovative Gerber designs to include the Gerber Mark 1 boot knife. Leaving Gerber he established Al Mar Knives, becoming the first specialty cutlery designer in the United States to offer original, exceptionally high quality knives and other edged tools.

Al Mar died in 1992 from a brain aneurysm. His Color Guard was arranged for by myself as both a close friend and confidant of Al’s and as a member of Company A, 1/19th Special Forces Group (ABN). Mar had supported the unit for some time and was an honorary member of our company.

Nick Rowe turned to fellow "Green Beret" Al Mar to co-design and produce the now legendary AMK SERE folder.

When Al and Nick Rowe were collaborating on what would become the AMK SERE Folder I was privy to the discussions and prototypes being conducted and shared between the two “Green Berets.” They became good friends along the way, with Al designing a limited edition Rowe Commemorative Knife to honor Rowe after the colonel’s assassination in 1989. Fewer than 50 sets of this, the rarest of AMK’s project knives, were made. I was asked to write the booklet that described Nick’s life and accomplishments that went into the beautiful shadow box.

The Al Mar SERE folder was the first such knife accepted for use by Special Forces. Fifty unmarked knives with rubber grips were delivered to Colonel Rowe at SERE. The commercial version would feature Micarta grips and the AMK “chop” on the blades.

The evolution of a cutting edge for SERE

The Crusader from Anglesey Lite Tactical and Hunting Gear is, in my professional opinion after several months of carry and use, the fitting evolution of the concepts Nick Rowe and Al Mar explored in their pursuit of a sturdy, reliable, well constructed small knife for SERE applications.

First, it is a fixed blade knife. This means there is no locking system necessary and when unsheathed it is ready for use immediately. It also means the knife is quiet – there is no loud “click” of a locking system being engaged. This is a major plus if you are in an escape or evasion situation.

Second, the false edge is sharpened, and I mean sharpened. This provides for faster and deeper penetration whether used as a make-shift spear for hunting game or close quarters applications with an enemy.

The Crusader’s grip panels are formed from Grolite (G-10). The steel is 440C, properly heat-treated and with the correct edge geometry for a knife designed for hard use and re-honing. The grip panels were co-designed by a veteran special operator with 12 years experience on the U.S. Secret Service Counter Assault Team, or “CAT”.

A trainer version, or “Blue Knife”, is made from the exact same materials as the Crusader is available and allows for realistic training. Anglesey takes a perfectly good Crusader and grinds down the edges. They then use blue blanks to do the grips and use blue Cerakote for the overall blade. It actually costs more to make the trainer than the Crusader, according to the maker.

A nicely thought-out thumb platform allows for swift indexing of the blade and its point during the draw. Sheathwork is Kydex and is very nicely formed and fitted to each blade.

Set #2 of the limited edition from Al Mar in honor of his friend, Nick Rowe.

As Al Mar pointed out to me time and time again during our visits — “Always remember that Form and Function go hand in hand. Of the two concepts, it is the latter which will determine whether or not you can trust your life to your “silent partner”. Your knife is first and foremost a cutting tool. Treated with respect, given the proper care before, during, and after use, it will serve you well.”

For more information and ordering you are invited to contact angleseyknives.com

The Anglesey Crusader

The Crusader is 21st Century successor to the AMK SERE folder and is pictured here with the Nick Rowe memorial coin Al Mar designed and had produced for the limited edition Rowe Memorial set.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR — An author and Special Forces historian, Greg Walker served with the 10th, 7th, and 19th Special Forces Groups (ABN). He retired in 2005. He is a Life member of the Special Operations and Special Forces Associations.

Today, Mr. Walker lives and writes from his home in Sisters, Oregon, along with his service pup, Tommy.

Great story Greg I was in the Philippines in 1989 with Nick the day prior to his assassination. He was a true supporter of what we were doing there in that region. It was a sad day for all of us the day we got the radio message.

De Oppressor Liber

Hi Ken, I’ll be sure to pass this message on to Greg. He may or may not see your comment on the website. Regards, Debra

What a great article, thank you for writing and sharing. I was in the 1st Ranger Bn in 1986 and attended the SF SERE C Course with a very small class of just SF guys and then me. Our class advisor was none other than Dan Pitzer. He would spend as much time as he could sharing stories with us and the importance of taking the training serious. It wasn’t hard sense the resistance training was not fun and sure felt real at the time. It was sad to hear about Nick and then years later to hear Dan passed. I am glad I kept Dan’s signed copy of Five Years to Freedom. Thanks again

Dave

Thanks for your comment. It will be forwarded it on to the author Greg Walker.