ERNIE PYLE,

The Soldier’s Journalist –

Ernie Pyle and sailors listen to war reports aboard USS Charles Carroll while enroute to Okinawa. (National Archives, 80-G-314410)

By Marc Yablonka

(This story originally ran in the summer 1995 issue of the National Amvet magazine)

From Anzio to Algeria, Sicily to Saipan, no war correspondent in history brought war from the foxholes to the folks back home like Ernie Pyle, whether filing from the cockpit of a B-29 Super Fortress or the mess hall of an aircraft carrier. As a Scripps-Howard Syndicate reporter, Pyle was the first to file “Home-towners”—so-called because the newspapers in the towns and cities of the GIs about whom he wrote always published his stories.

Pyle’s dispatches truly captured the horrors of the Second World War.

“They say you never hear the shell that hits you,” he wrote from Tunisia in April 1943. “Fortunately, I don’t know about that, but I do know that the closer they hit, the less time you have to hear them. Those landing within a hundred yards, you hear a second before they hit. The sound produces a special kind of horror inside you that is something more than fright. It’s a confused form of desperation.”

At 42, almost twice the age of the soldiers whom he befriended and championed, Pyle was extremely thin, disheveled, and down to earth. He loved carousing and drinking with fellow journalists, according to his namesake, the late Richard Pyle, an Associated Press reporter who headed the AP’s Saigon bureau for three years during the Vietnam War.

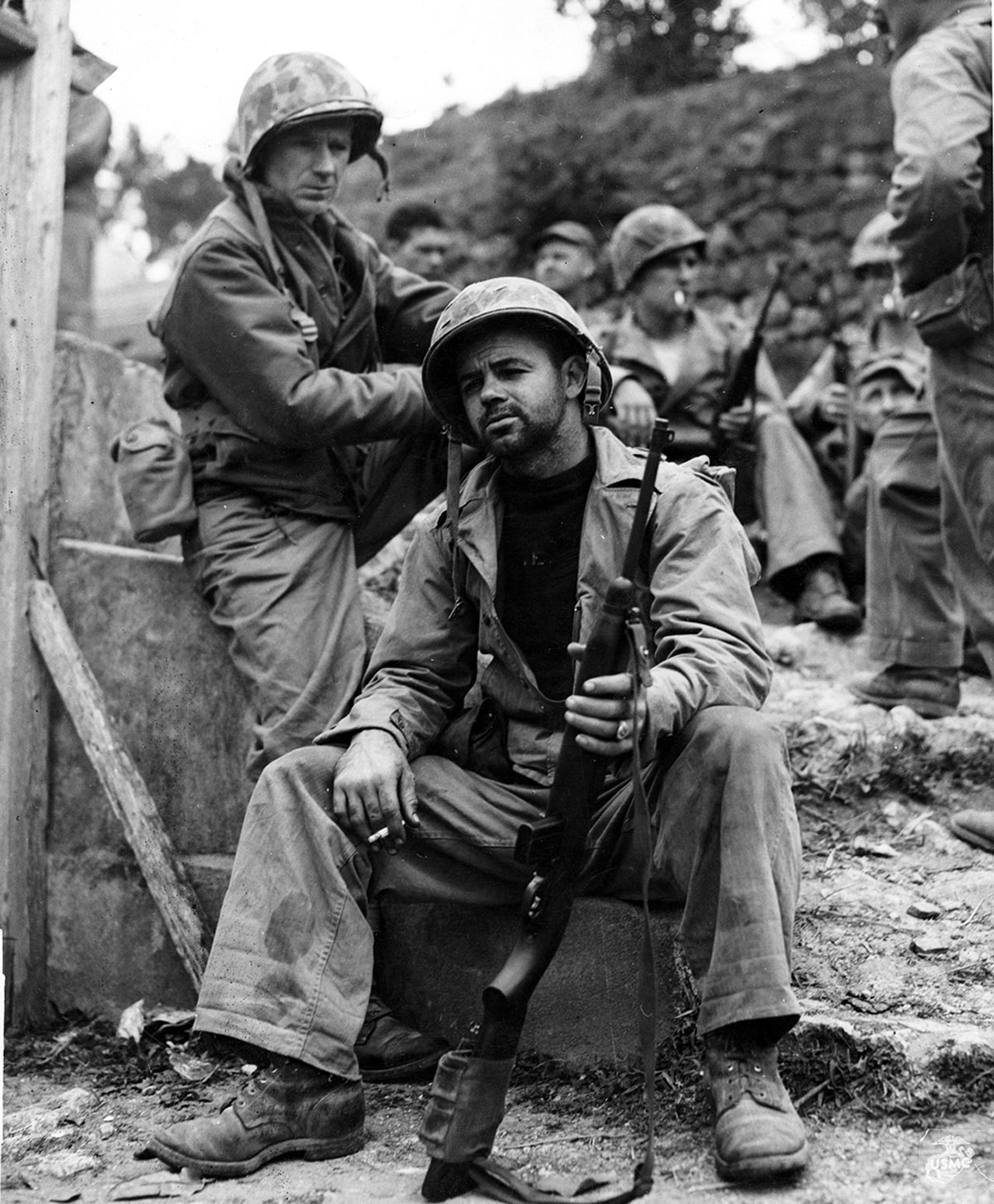

Ernie Pyle rests on the roadside with a Marine patrol. (National Archives, 127-N-116840)

"[He was] graceful about his beloved `god-damned infantry' clogging through the mud, the bomber pilot buffeted by flak, the coxswain steering his landing craft toward the beach," said the AP's Pyle.

He could do so, according to biographer David Nichols (Ernie's War: The Best of Ernie Pyle's World War II Dispatches ), because he didn't care as much about the news as he did about those making it. Added to that was the anonymous tone of previous war coverage that he avoided.

Pyle brought into American homes the crew of a crippled B-29 inching home after being hit by flak from Japanese fighters.

"Five fighters just butchered him. And there was nothing our boys could do about it. And yet he kept coming. How, nobody knows. Two of the crew were badly wounded. The horizontal stabilizers were shot away. The plane was riddled with holes. The pilot could control his plane only by using the motors…somehow, he made it home. He had to land without controls. He did wonderfully, but he didn't quite pull it off," Pyle wrote.

?"The plane hit at the end of the runway. The engines came hurtling out, on fire. The wings flew off and the great fuselage broke into two and went careening across the ground. And yet every man came out of it alive, even the wounded ones."

?Pyle, whose dispatches filled six books, was among the earliest reporters to write that, in addition to its horror, war has a humorous side. One such dispatch, filed from the Mariannas, tells of a GI using an outdoor commode.

"Suddenly he was startled…here he was caught with his pants down…and in front of him stood a Jap with a rifle," he wrote.

"Before anything could happen, the Jap laid the rifle on the ground in front of him and began salaaming up and down like a worshipper before an idol."

According to Pyle, the Japanese soldier had been searching for an American to surrender to and concluded that finding one on a toilet would be the easiest way to give himself up.

Ernie Pyle and PFC Urban Vachon rest by the roadside on the trail at Okinawa. (National Archives, 127-N-116846)

Pyle first reported on troops in the European Theatre. By the end of the war, however, he found himself reporting from the South Pacific on a part of the war he found difficult to understand. For one thing, he spent much of his time aboard Navy vessels where, when the action was nil, life was boring.

“Now we are far, far away from anything that was home or seemed like home. Five thousand miles away from America…twelve thousand miles from my friends fighting on the German border,” he wrote from Saipan in February 1945.

Before Pyle’s transfer to the Pacific Theatre, “so many people wanted so many things!” wrote David Nichols. “People on the street wanted his autograph. Helen Keller wanted to run her hands over his face. John Steinbeck wanted to talk. Wives and mothers wanted information about their husbands and sons. Lester Cowan wanted to confer about problems with his movie The Story of GI Joe (based on Pyle’s book Here is Your War).”

Pyle’s reaction was to retreat from the life the war had made for him.

“I feel sad because it has given me the big things of life, and taken away the precious little things,” he wrote from San Francisco during some well-deserved R & R (rest and recuperation) in January 1945.

“I like people …and so it hurts me to have to shut off the phone calls in a hotel…turn letters over to a secretary…tell old friends that I can’t see them today—maybe tomorrow.”

“Lost a Buddy” sign stands. (U.S. Army Signal Corps)

Ernie Pyle died on April 18th, 1945, almost four months before the war’s end, on the tiny island of Ie Shima during the campaign for Okinawa.

After covering a US Marine advance, he later joined four GIs from the 77th Infantry Division in search of a command post site for the 305th Regiment. A Japanese sniper opened up on them, forcing them out of their Jeep, killing Pyle.

He was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart.

In a dispatch filed two months before his death, of the soldiers Pyle had come to know so well, he wrote, “Each one thinks his war is the worst and the most important war. And unquestionably it is…”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR — Marc Yablonka is a military journalist whose reportage has appeared in the U.S. Military’s Stars and Stripes, Army Times, Air Force Times, American Veteran, Vietnam magazine, Airways, Military Heritage, Soldier of Fortune and many other publications. He is the author of Distant War: Recollections of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, Tears Across the Mekong, Vietnam Bao Chi: Warriors of Word and Film, and Hot Mics and TV Lights: The American Forces Vietnam Network.

Between 2001 and 2008, Marc served as a Public Affairs Officer, CWO-2, with the 40th Infantry Division Support Brigade and Installation Support Group, California State Military Reserve, Joint Forces Training Base, Los Alamitos, California. During that time, he wrote articles and took photographs in support of Soldiers who were mobilizing for and demobilizing from Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom.

His work was published in Soldiers, official magazine of the United States Army, Grizzly, magazine of the California National Guard, the Blade, magazine of the 63rd Regional Readiness Command-U.S. Army Reserves, Hawaii Army Weekly, and Army Magazine, magazine of the Association of the U.S. Army.

Marc’s decorations include the California National Guard Medal of Merit, California National Guard Service Ribbon, and California National Guard Commendation Medal w/Oak Leaf. He also served two tours of duty with the Sar El Unit of the Israeli Defense Forces and holds the Master’s of Professional Writing degree earned from the University of Southern California.

Fantastic article. Marc Yablonka captured the essence of Ernie Pyle and gave me even more insight into a hero of mine.

Mare,

Thank you for your kind words! Coming from a journalist such as yourself, who has chronicled and photographed our Soldiers and Marines in the throes of battle, I’m honored to read them!

Marc

When I lived on Okinawa, we used to go to Ie Shima every year and spend the day cleaning up the grave site.

Ken,

What an honor that must have been for you as a young man! And now, as the proud American adult that I know you to be, I imagine the honor gained from what you and other Okinawans did rests even stronger in your thoughts!

Marc