Coming to America

By Colonel John Gargus (USAF, Retired)

Originally published in the January 2019 Sentinel

Early in 1949 the family started talking seriously about going to the USA. We always had an open invitation from grandmother Julia, but father’s position had always been that we would have America in Czechoslovakia during our own lifetimes. However, after the Communist seizure of power, life in the USA became very attractive.

Mother acquired her U.S. citizenship by being born in Pennsylvania and her children inherited a claim to full American citizenship provided they established permanent residence in the USA before their sixteenth birthday. That was in accordance with then existing McCaran Act sponsored by one Nevada Senator. I was already completing my fifteenth year and Milan with Vierka were almost ten years old. After the war it was possible for all of us, including our father, to travel to the USA. As a husband of an American citizen, with citizenship eligible children, he could have immigrated to the USA with his family.

But now, with the new communist regime, father’s political past, and the worsening relationship with the USA, our hopes for a departure as a family were gone. We would have to get out of the country illegally and seek political asylum in the West, behind what became known as the Iron Curtain. We learned from listening to broadcasts from exiles in London, Paris, and Munich that West Germany was full of displaced persons camps for people who either escaped to the West or opted not to return to their homes because they came from lands occupied by the Soviet Red Army. Most of them wanted to immigrate to the USA. Many, just like us, had some legal claims to become American citizens. The United States had a problem absorbing all those who wanted to come. Many other countries, Canada, Australia, and places in South America, opened up their gates to ease the demand for passages to the USA. We must keep in mind that commercial trans-Atlantic air travel had not yet been established and passages on ships were fully booked. People had to wait months to get out of West Germany and the number of escapees from the east side of the Iron Curtain kept increasing.

Passports

Our parents understood this, so the first decision became to have all three children get U.S. passports and leave together without stopping in a displaced persons camp in Germany. Then, at a later date our parents would find some way out that could include a stay in one of those camps. We went to a photo studio and had a group passport photo made. Parents cautioned us not to say a word to anyone about our plans because we could face certain repercussions if something went wrong. We all understood that. I don’t know how father communicated with the U.S. consulate in Bratislava, but he learned that the best course of action would be to send me to the USA first because as the summer passed, I had less than one year to get out before my sixteenth birthday. With that decision, we had a new passport photo made just for me. Then grandmother Julia, with some financial assistance from grandfather’s half-brother Steve Mihok from Lorain, Ohio, prepaid my travel to the USA on any available ship. As I learned later, with that done, the consulate in Bratislava became obligated to issue me a passport valid only for direct travel to the United States.

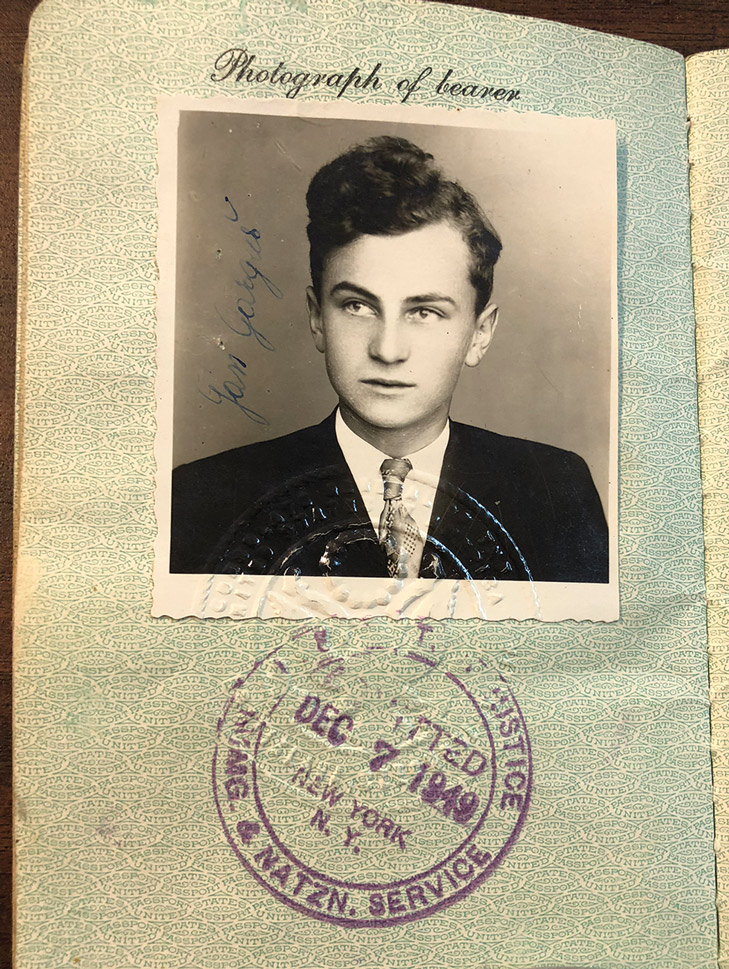

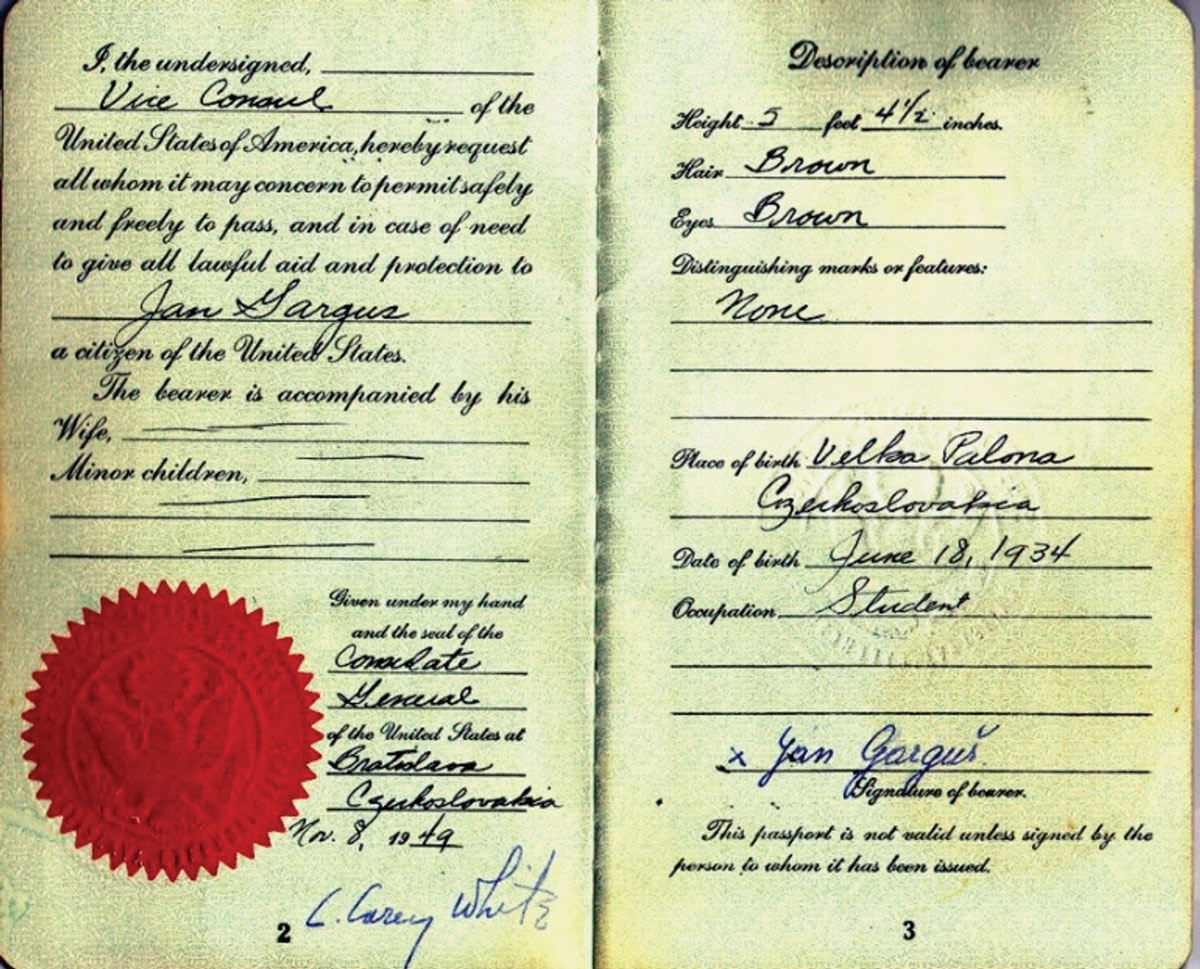

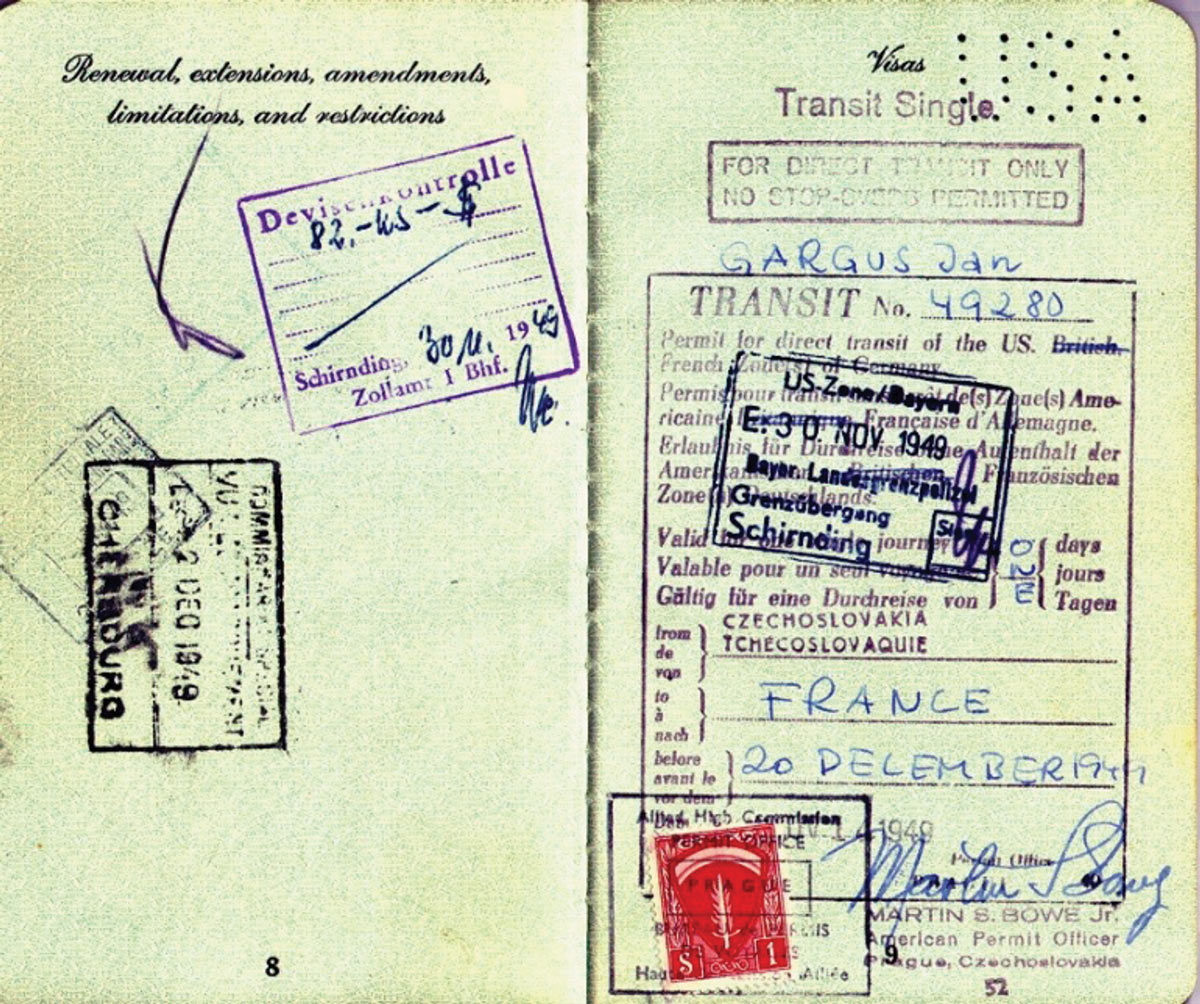

When the 1949-1950 school year began in September, we already had a firm decision to have me travel alone as soon as my transatlantic passage could be arranged. Father and I went to Bratislava and obtained my passport on November 8, 1949. Father had a long private discussion with the U.S. Consul Mr. Carey White. The thing I remember the most was his cautioning me about not telling anyone that I had an American passport. This was to prevent anyone from creating roadblocks to my departure before my time to get to the USA would expire. My passport was good for only four months. If I didn’t make it out in that time, it would have to be renewed, but never past my sixteenth birthday on June 18, 1950.

Pages from young John’s one-way passport to the USA.

In Bratislava we stayed with a Poloma native, a former classmate friend of father, who worked in one of the banks. The story father told him was that we came to the American Consulate because grandmother Julia was signing over some of the family property as my inheritance. Obviously he was not trustworthy enough to be told the truth.

On the way home the train had a long lay over at a station in Zvolen. I toured the station alone and ran into two of my professors who were killing time just as I was. I used the same story about the inheritance to explain why I was not at home in school. I learned from them that they were coming back to Rožč on the same train after getting married in her family’s home village. She was my French professor and he taught history and Slovak literature. When I told my father about this encounter, we decided that I would not get a sick excuse for missing two class days and tell my homeroom teacher the same story. As it turned out, it was not necessary. Our first class was with our homeroom professor Gunda, a good friend of the newlyweds, who proclaimed to the whole class that Mr. Gargus was absent for couple of days because he was inheriting an estate from his American grandmother.

Life in the interim

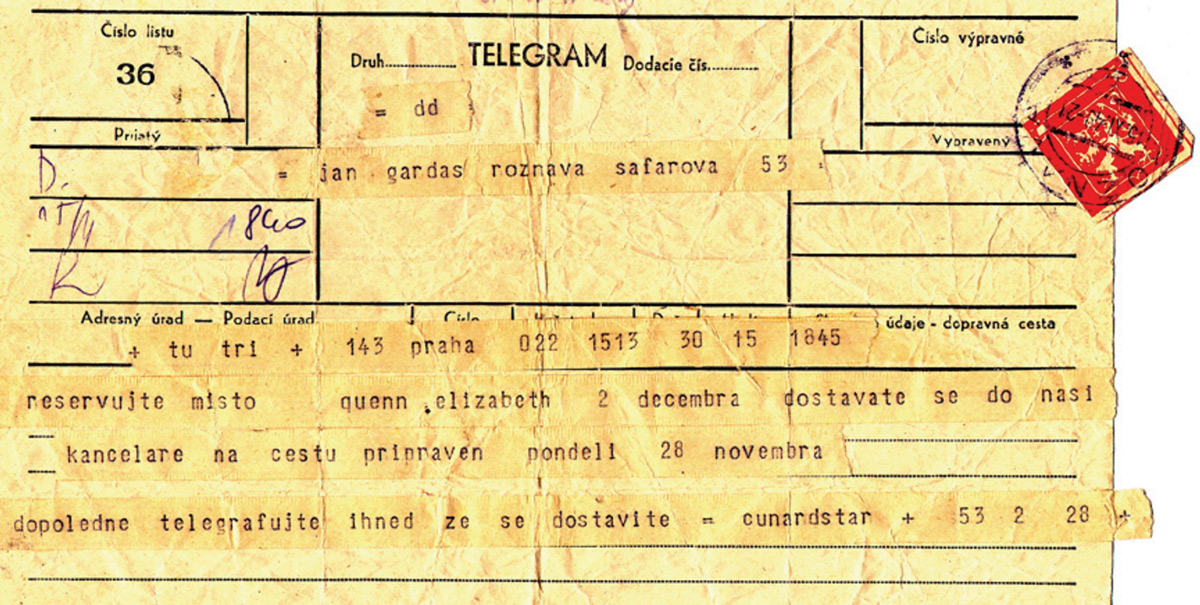

After that our life returned to normal. We did not expect an early departure for me. Winter was coming and I was already looking forward to skiing and ice skating with friends after school and especially during the three week Christmas school holiday. But on November 15 we received a telegram instructing my parents to have me come to Prague on November 28 ready to travel to the USA. Wow, all of a sudden I had only 10 days of school left and then I’d be gone.

A couple of interesting things happened in school just before that. Comrade Andrejkovičá came to our class with a short briefing on a new student club that was just forming. It was for young people who showed support for and solidarity with the youth of the Soviet Union. She distributed membership identification cards and showed us how to fill them out. She also began collecting a 2 crown annual membership fee from everyone. Two crowns bought a small stamp that was then pasted into a dated square showing that annual membership fee had been paid. Before that we had several communist front organizations for students and membership in each had been voluntary. She did not ask for volunteers here. I had never joined any group before and I hesitated here. Three classmates borrowed money from me and I had four crowns in change coming back to me. She gave me a stamp and 2 crowns back in change. I took it and joined the crowd for a 100 percent classroom participation. What could be wrong with joining a club that professed friendship for the Russian youth?

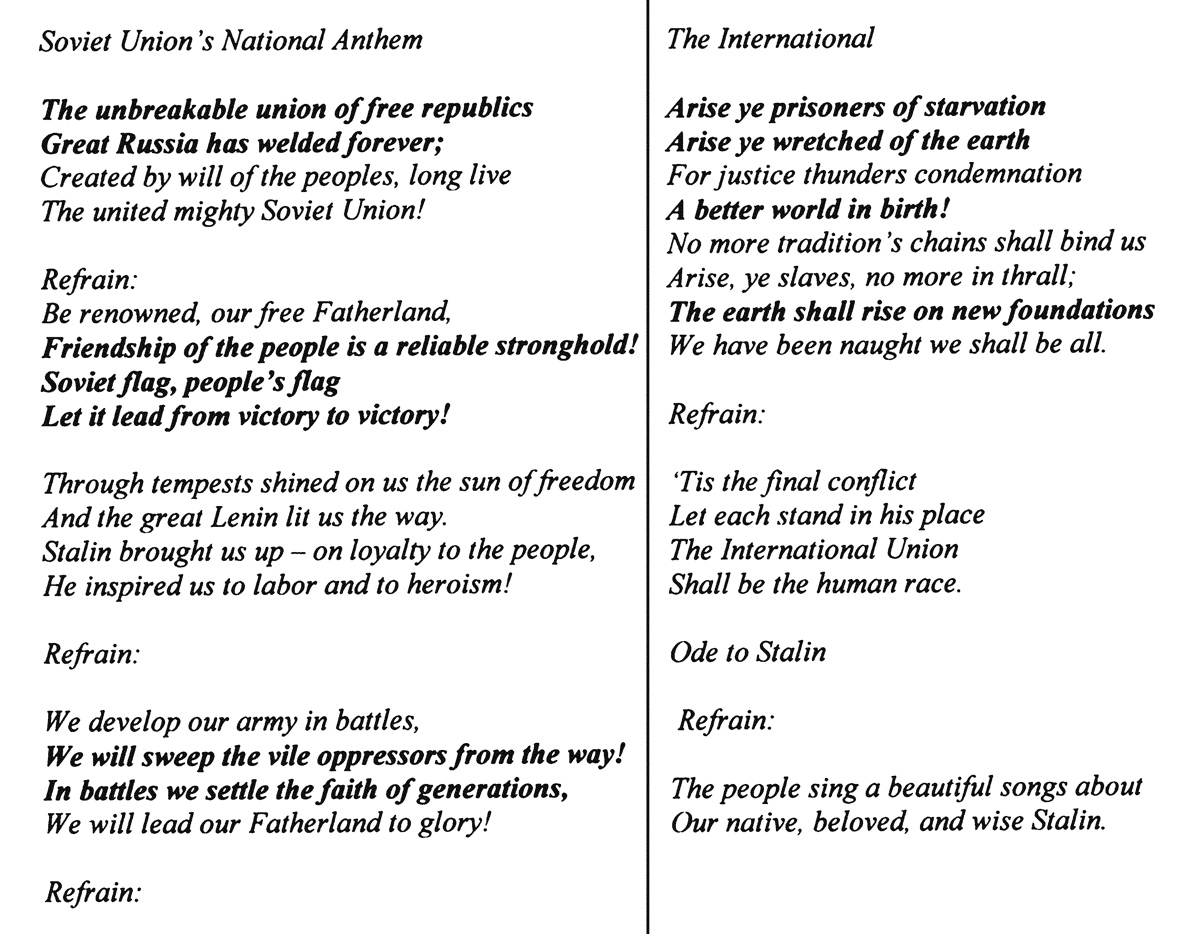

Next event, on Monday, November 21, was our classroom Russian essay for that month. We expected that its theme would have something to do with the Bolshevik October Revolution, but we got something unexpectedly tougher. Professor Bellavina passed out our essay notebooks and wrote the following topic on the blackboard: “The USSR was victorious in the war for peace and the USSR will be victorious in the fight for freedom.” We all cringed and many voiced their surprised displeasure at such a difficult theme that had to be completed in the remaining 40 minutes of class time. But I got a sudden inspiration. Somehow my thoughts focused on the lyrics of the Russian national anthem. That frequently heard song had most of the theme for our assignment. There was also the Communist International with more appropriate lyrics and a few other Russian songs that celebrated Russian victories, and make glowing predictions for a glorious global future from which I could borrow other theme fitting phrases. All I had to do was to pick out the appropriate lyrics and expand them with phrases containing quotes and slogans we were taught to recite in our well received tribute to Lenin. There wasn’t much originality in the collage that came to my mind, but I thought that it would be a good satirical joke to regurgitate many of the exhortations to which we had been exposed.

These are the two anthems I leaned on in my composition. Bold text shows the lines I used. English translation does not do the words justice. They go together much better in the original Russian.

The essay

I began by stating that our essay’s theme was prophetically immortalized in the lyrics of the USSR’s national anthem and I simply wrote down much of its text. I paraphrased the beginning about the unbreakable union of free republics for eternity forged by the vision of the great Russia. Then at the appropriate time I threw in another fitting sentence about the Soviet flag that would lead people from one victory to the next. In between and everywhere, without further identifying the sources, I borrowed from the Communist International about workers arising and righting the wrongs of the past and from several other songs that glorified the accomplishments of the Soviet Union and its fatherly leader Stalin. There was an ode that the people of Russia sang to their wise and beloved leader who would lead other struggling people to freedom in a universal proletarian brotherhood. I also gave some credit to Lenin for inspiring so many to rally to the side of the working class. I concluded that the prophecy of the Soviet Union’s anthem would surely come true and that there would be many more victories until all the people of the world would live in absolute freedom from oppression.

I did not consider my essay to be a masterpiece, just a witty collage of everything we were receiving in our indoctrination to Marx-Leninism. How I would love to have an exact copy of what I wrote that day! My essay received an unexpected praise from professor Bellavina. On the following Thursday, just two days before my departure, she came in with our graded essays and singled me out for writing the best composition ever. She had me read it to the whole class and gave me a big hug. I was embarrassed by all of this, but to my comfort, most of my classmates saw the satire in my literary effort and envied me for coming up with such a clever idea. On the other hand, Bellavina, who thought that my tribute to the Soviet national anthem was a very catchy theme gimmick, must have been gratified by the rest of the easily traceable phraseology of my composition. It clearly showed her that I had learned a lot and that I could recall and use it in an appropriate context. She said that she would have me read it to some of her other classes. I know that she read it to one class on Friday. That was sure the last of it because on the following Monday I was already in Prague ready for my trip to the USA.

My summons for travel to the USA — "Reserved space, Queen Elizabeth, 2 December. Come to our office ready to travel on Monday 28 November before noon. Send a telegram that you will be here."

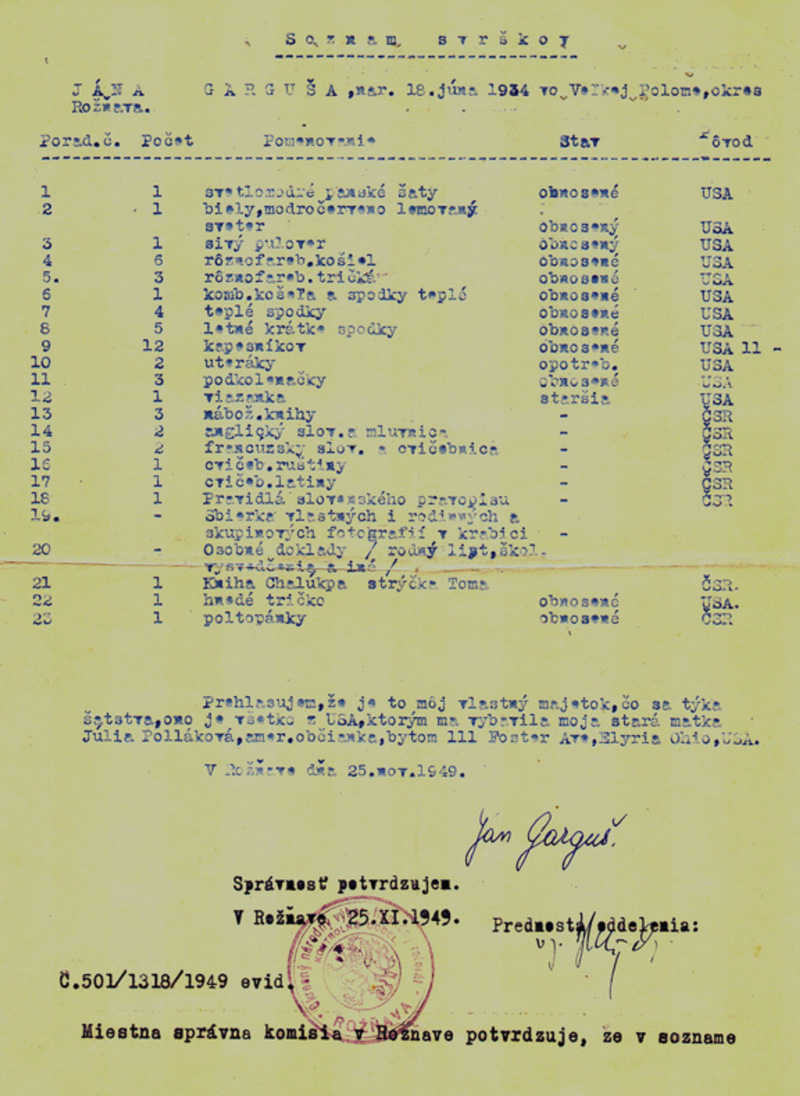

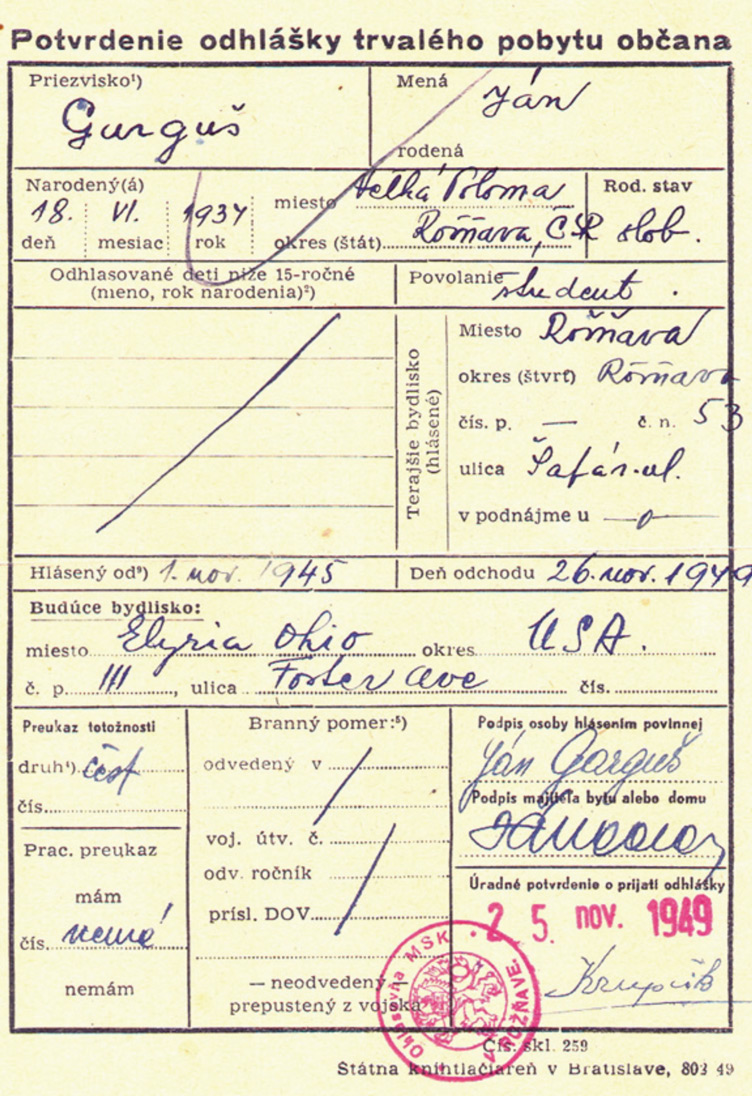

All of a sudden I had so much to do and just a few days left to get it done. Mother took care of my clothing, almost all of which had been sent to us by grandmother Julia from America. We were getting regular packages from her every month. My winter topcoat and cap were the only non-U.S. items I wore on the trip. The only personal things I brought with me were my complete Slovak Republic stamp collection, religious books (New Testament, hymnal and couple of prayer books), Slovak-English dictionary, rules for proper Slovak writing and a parting gift from my parents — a book “Chalúpka Strýč Toma – Uncle Tom’s Cabin”. Father prepared an inventory of everything mother packed in my mid-size leather-look-alike suitcase made out of cardboard. He had the inventory list notarized. He also took me to the chief of police in Rožč to obtain a written statement that I was departing my home to live in the USA, giving my future address in Elyria, Ohio. Father knew the police chief well from his association on the County National Committee.

The notarized inventory listing of what I was bringing with me to the USA.

A police certificate declaring my intention to establish new residence in Elyria, Ohio.

Saying goodbye

Then I needed to say my farewells to several people. Three evenings preceding my departure were dedicated to that. The first night I went to Vyšná Slaná to say good by to the Sopócys, Petráškos and Emericis. The next night I went with my father to Poloma to see the Zatroch and Garguš-Šimšík families. Then on the night before my departure I had about dozen classmates come to our house. I invited them on the last class period of the day. Most thought that I was joking about going to the USA. I had to reassure them that it was really so at the end of the school. They all showed up. Mother made some open face sandwiches and cookies. Father provided some rosebud vine. Drinking age was not a factor at that time. We all had a glass of it.

The next day, Saturday, 26th of November was my last day in school. I went to my homeroom professor Ladislav Gunda and told him about my imminent departure. By that time the word was spreading throughout the school. Curious and some envious students surrounded me during classroom breaks. I got the word that the principal Andrejkovic wanted to see me. I went to his office with professor Gunda. He wished me well. He knew about my mother being born in America. He must have learned a lot about my father’s biography from the Communist Party files because he was a very active party member. He surprised me by telling me that he was also born in Pennsylvania where his father had been a migrant coal miner just as my grandfathers had been. Then he led me to the large office room where I encountered most of the professorial staff. I thanked all of them for their work with me. When the bell rang to resume classes, I was finished. I returned to my classroom for my last period there. I emptied my narrow desk and left the classroom teary-eyed. Most of my classmates walked with me outside along the school fence all the way to the Cathedral.

A few hours later I left our Vinegar House. I was surprised by how many classmates and friends were waiting for me at the gate. They followed us — my mother, father, Milan and Viekra — all the way to the railroad station. My train had about a five minute stopover at the station so there was plenty of time for well wishing and tears. My parents went with me to Prague. Milan and Vierka remained behind with my grandfather.

We spent three nights in Prague with the Zahradnicek family. We learned from them that my godfather Linczényi managed to leave the displaced persons camp in West Germany and immigrate to America. They did not have his address but were sure that he settled in a town that was named after a shoe manufacturer from Czechoslovakia named Bata. He had a shoe factory in that town and godfather was employed by him. The biggest Bata shoe factory in Slovakia was in Svit, the town where he lived with his family before his escape to the West. I was to locate him after my arrival to the USA.

We also learned that Mr. Zahradnicek — my godfather’s brother-in-law — was about to lose his job at the ministry because of ongoing political purging. He anticipated a punishing new job assignment and informed us that he had already made up his mind to send his older son Otto to his grandparents in Poloma so that he could attend gymnázium in Rožnava. He had no future for a follow on education from a school in Prague and hoped that by going to a far away Rožnava he would improve his chances to go to some university. This plan was eventually carried out with success. Otto graduated with my former classmates and became a successful metallurgical engineer. Anita and I visited him and his wife Milena in Prague in 1999.

Preparing for departure

We had a very busy day in Prague on Monday, November 28. We stopped at a bank first and exchanged currency into $89.00. The bank entered this amount in my passport. I had to produce a foreign passport to make this a valid currency exchange.

Then we went to the consulate at the U.S. embassy. We met several officials there and some of them had a detailed discussion with my parents while I busied myself with available magazines full of color photographs of my future homeland. We spent seven of my newly acquired dollars to pay for a non-stop transit visa through the occupied zones of Germany to France.

Then we went to the travel agency where we learned about my travel arrangements to New York. I would be traveling in a company of Slovak Americans who were returning to the USA after visiting families in Czechoslovakia. Father introduced me to a gentleman in his late sixties, Mr. Ševčík, who had agreed to be my adult escort all the way to New York. That arrangement had been made earlier at the U.S. embassy, but I did not see him there. We were going to depart from Prague on November 30 and arrive in Paris on December 1. We would spend the night in Paris and then proceed to Cherbourg where we would catch the Queen Elizabeth on Friday afternoon of December 2. We would dock in New York on Wednesday, December 7. We had no idea who would meet me there. Grandmother Julia and John, who lived together in Elyria in a duplex house, had not yet been notified that I was coming. Father composed a telegram for them right there telling them to expect me at the port of New York when the ship Queen Elizabeth arrived on December 7.

I was very excited over my impending travel. It was finally happening. Leaving my family behind did not bother me that much because I knew that we would be reunited in the U.S. perhaps within one year. Milan and Vierka would follow me soon and mother with father would get out of the country somehow. My thoughts were only of a new life ahead of us in a country that would give us greater opportunities with a better future. These thoughts were reinforced by the assurances of my parents when I departed from them at the Woodrow Wilson railway station. Leaning out of the window of departing train, I lost the sight of them as the train curved away from them.

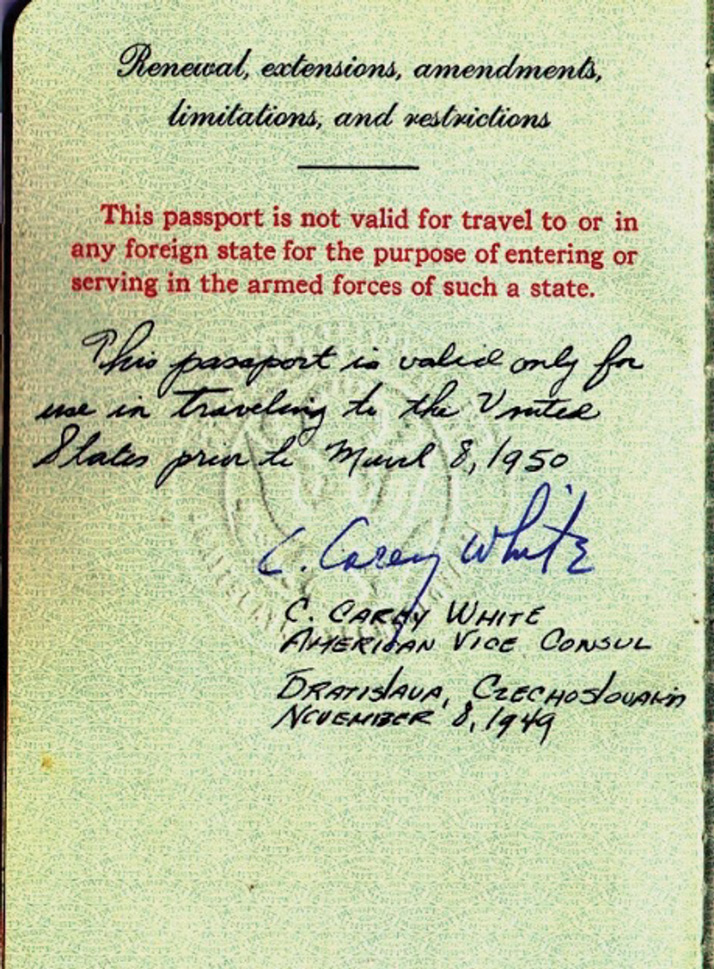

These two pages of my passport show entries made by immigration agents in Germany and in France. Page 8 has an indistinguishable green on green stamp with an initial in a form of letter K. Only the date – 30 November can be made out. This stamp imprint and the mark must have been made by the agents in the hallway outside of our car compartment. Departure from Cherbourg stamp is over the entry into France stamp. Page 9 is devoted to my transit through the occupied zones of Germany.

On the train

There were 26 of us going to the USA that day. Among us were three other boys who were going to join their fathers already living somewhere in the USA. I soon found out that they were not part of our travel group even though they had assigned adult escorts from the members of our group. We were all in one railway car with compartments for eight passengers. I sat on the right hand side by the window and stowed my suitcase in the overhead rack by the door in the opposite corner. That way I had it within my sight all the time. I could not get separated from it. All I had with me was in it. I soon took off my cap and the overcoat and hung it together with the coats of others.

About two hours later we stopped at the border. Immigration agents entered the railroad car and moved methodically from one compartment to the other. Ours was the second compartment. We had our passports ready when they came to us. The first man was interested in the money we had on us. He was stamping something on a passport page and then scribbling on it. I did not get to deal with him because the man who entered the compartment right after him reached for my suitcase and asked whose it was. I moved over to him and opened it for him. He was immediately impressed by the notarized, detailed inventory list that was on top. Nevertheless, he poked his hands here and there feeling around my books and clothes. He did not make a mess of things, but I had trouble closing my suitcase. He had fluffed it up sufficiently that things had to be tightly compressed again before it would close. All that time I had my ready passport under the uncooperative suitcase. By the time I finished and returned to my window seat, the first man who handled the passports was done with the compartment and moved on.

After a while another immigration agent came in and collected all our passports. He left our compartment with them but did not go far. I could see his back through the side window of our compartment. He was talking to someone. His elbows were bent and it seemed like he was shuffling our passport or showing them to some other agent. That didn’t take long and he handed all eight passports to our traveling companion who was standing at the door. He smiled, waved at us and wished us a good trip in Czech. That was it. We sat there for a long time before we heard the sounds of immigration people leaving our car. Then there was another long wait before the train started moving again.

I don’t know exactly when we crossed in to West Germany, but the train didn’t travel very far before we stopped again and new immigration agents came to check our passports and visas for entry into the U.S. occupation zone of Germany. They had us count our money and this time the stamp showed that at border crossing in Shirding I had $82.00 on my person. Agent had no interest in my small crown coins I was carrying with me as souvenirs. There was another long wait before the agents departed from our car and we started moving again.

Mr. Ševčík’s tale

All that time I became a little bit uncomfortable because my escort, Mr. Ševčík, kept wiping his tears and looking right at me. I thought that he was sad because he’d probably never return for another visit. But his look at me was puzzling. Then, as we were on our way once more, he asked the man next to me to change seats with him. He ended up on my left and began telling me a stunning tale. He called me a very lucky young man. Of course I knew that much. But what followed gave me goose bumps. He told me that the reason I was on this train with this travel group was that his wife had died more than two weeks ago and that I had taken her place on the train and on the Queen Elizabeth. He said that our group‘s tour list still had his wife’s name on it not mine and that I was traveling without an exit visa, that he was to send my father a telegram from the first stop in Germany to a friend’s address in Prague if I got stopped at the border. He was thoroughly briefed on my situation at the consulate and agreed with my parents to take the risk.

I was stunned. What he just told me was incredible, but very true. It explained why I had to travel on such a short notice. I don’t remember how I replied to him, but I couldn’t get over it. Thoughts of this kept me up all night. I don’t think I slept a wink the rest of the way to Paris. I realized the great sacrifice my parents made for me and I began to fear the consequences of my departure from them.

I also wondered what would have happened to us after getting to Prague if Mr. Ševčík had not agreed to go along with the family plan. How would have I acted had I known about the potential peril of my crossing the border? Surely, the immigration agents were not diligent enough in examining our passports. They must have thought that we were all Slovak Americans returning from a visit to our families and wanted us to have a pleasant impression of the country. I was dressed in easily identifiable U.S. made clothing. My domestic top coat and cap were hanging on the hook. Obviously I passed as one of the returnees and somehow they did not pay attention to the names in the passports. Was this what my parents and the U.S. officials at the consulate hoped for? Once on the ship, I spoke with the three young boys who were sailing to join up with their fathers. They all told me that the immigration agents questioned them on the train about the reasons why they were leaving the country, where their fathers lived and if they planned to return to Czechoslovakia some day. Mr. Ševčík was right. I was one very lucky guy!

Paris

We arrived in Paris at the north railroad station called Gare du Nord on the first of December. One travel representative met our group and had us follow him to a hotel about two blocks away. I had a small room with Mr. Ševčík. It had only one double bed. After all, it was supposed to be for him and for his wife. We slept together. Even though I was very sleepy and it was cold and drizzly on the street, I was so curious about Paris that I began walking the streets. Walking drove the sleepiness away and I visited various stores, marveled at the variety of merchandise, and used some of my limited French asking basic questions, namely in which direction is the railway station Gare du Nord. Even though I knew that I was getting farther and farther away, I wanted to be sure of the direction I had to go to find the station and the hotel, whose name I did not bother to remember. I stopped in two restaurants to eat and struggled with the unusual script on their menus. I paid with dollars. They were glad to take them off my hands. Finally I made it back to the hotel. Mr. Ševčík was worried about me. It was already getting dark. I was exhausted and I went to sleep very quickly.

We left Paris the next morning and arrived at war-torn Cherbourg early in the afternoon. Damage from the war was still visible at the port and the Queen Elizabeth could not yet come to the piers. She was anchored in deep water about a mile from the shore. We took a ferry to her broad side and filed on board just like in a movie scene, except there was no crowd to wave at us from the pier. Piers, still under repair were at least a mile behind us. It was about 5 p.m. When I made it to the topside from our small four person cabin. It was raining and the land — the European continent — was already out of sight.

About the Author:

John Gargus was born in Czechoslovakia from where he escaped at the age of fifteen when the Communists pulled the country behind the Iron Curtain. He was commissioned through AFROTC in 1956 and made the USAF his career. He served in the Military Airlift Command as a navigator, then as an instructor in AFROTC.

He went to Vietnam as a member of Special Operations and served in that field of operations for seven years in various units at home and in Europe. He participated in the air operations planning for the Son Tay POW rescue and then flew as the lead navigator of one of the MC-130s that led the raiders to Son Tay, for which he was awarded the Silver Star.

His non-flying assignments included Deputy Base Command at Zaragoza Air Base in Spain and at Hurlburt Field in Florida and a tour as Assistant Commandant of the Defense Language Institute in Monterey, California.

He retired in 1983 after serving as the Chief of USAF’s Mission to Colombia, having accrued more than 6,100 flight hours, including 381 combat hours in Southeast Asia. In 2003 he was inducted into the Air Commando Hall of Fame. He has authored two books, The Son Tay Raid: American POWs in Vietnam Were Not Forgotten, published in 2007, and Combat Talons in Vietnam: Recovering a Covert Special Ops Crew, published in 2017. He has been married to Anita since 1958. The Garguses have one son and three daughters.

Leave A Comment