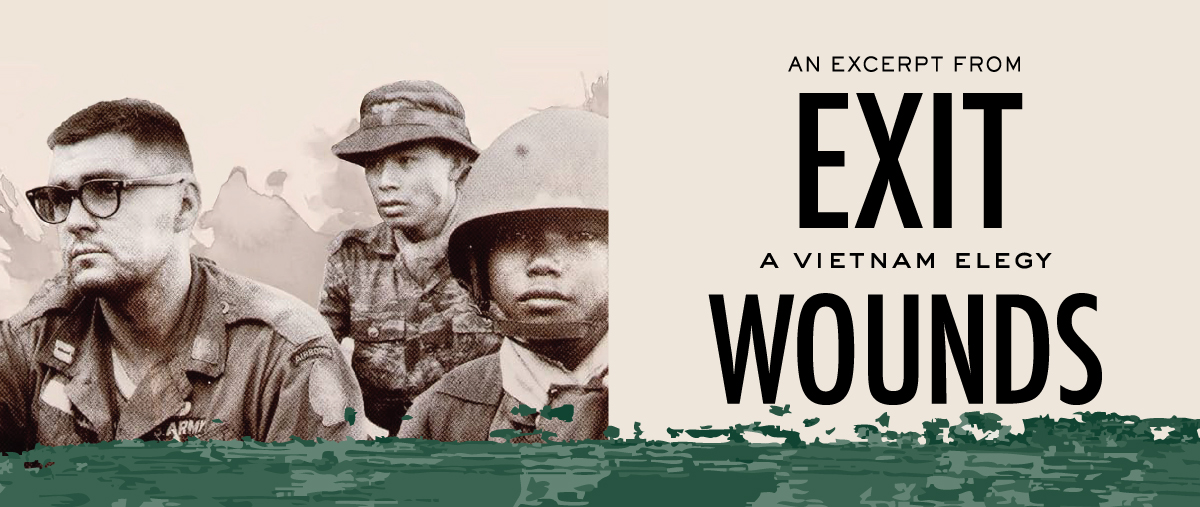

By Lanny Hunter

From, Exit Wounds: A Vietnam Elegy, published by Blackstone Publishing Inc., October 10, 2023, pages 1-20, reprinted with permission.

ONE

Night Medevac

August, 1965, II Corps, South Vietnam

I knelt in the chill, middle-of-the-night blackness near the chopper pad. Y-Kre, my Montagnard interpreter, knelt beside me, clutching my medical kit. The sandbagged perimeter of Detachment C-2, directly to our rear, was little more than an invisible, ominous presence. I shifted my M16 in my hands, conscious of the fact I had been flipping the safety on and off in a nervous rhythm. I hated night medevacs. I didn’t feel that good about daylight runs either, but the night belonged to Mister Charles.

The request for a medevac from Duc Co created special apprehension. Situated near the Cambodian border, Duc Co was always in trouble. I had been rousted from my hootch by the duty officer. The E-6 in the commo bunker vacated his chair. I sat at the single sideband, keyed the mike, and gave my call sign. “This is Column, over.” The voice of the medic was sheathed in static. A Montagnard soldier had been shot “right between the fuckin’ eyes.” Incredulous, I began the military communication tango. “Please verify that transmission. Over.”

The medic confirmed the location of the wound. The soldier was alive and his vital signs stable. “Can you come pick him up? Over.”

I hesitated. “I’ll see if the Dust Offs will fly. Out.”

I called operations at Camp Holloway and explained the situation. It was only a Yard who was wounded, not an American. It gave everyone an out not to risk a night medevac. I hoped the pilots would decline the run. To my chagrin, they said they’d fly. I wished I had refused the medic’s request. I had counted on a Dust Off pilot to refuse. He probably didn’t want to go either. It was difficult to show timidity in front of comrades. People were killed by courage, cowardice, bravado, bad luck, carelessness, and incompetence.

I strained to hear the sound of the Dust Off’s approach. The first inkling was the subtle pulse of rotors against my ear drums. The increasing roar of the engine never overcame the gut-tightening whop-whop-whop of the rotors. Landing lights flashed on. The chopper had a white oval with a red cross emblazoned on the nose, not that the emblem prevented the Dust Offs from being fired on. The Huey touched down on the perforated-steel plate. Y-Kre tossed my medical kit through the hatch. We had barely clambered aboard when the chopper lifted off, tilted tail-up, and headed southwest toward Cambodia.

The crew chief passed me a headset. I slipped off my beret and adjusted the headphones, listening as the pilot tuned past frequencies. Armed Forces Radio gave encouragement: Keep your weapon clean, guys. Static interference. A snatch of some guy wailing about winners and losers and times a-changin’… Advice on foot care: Your feet may save your life. The pilot settled on Tony Bennett: I left my heart in San Francisco… It could make you weep.

I settled back against the bulkhead, cradling my M16, and marveled afresh at the skills of chopper pilots. Ignorance of another’s expertise makes a mundane skill seem a marvel. The pilot flew on a specific azimuth at an airspeed calculated in knots and at an altitude intended to avoid flying into a mountain. The sky above was black. The jungle below was black. There were no landmarks. No mountain silhouettes. The pilot flew into the black abyss of Indian Country. Flying into unknown but miscellaneous, plausible catastrophes.

Unexpected weather, for starters, changed every calculus. Mechanical difficulty lurked inside the Lycoming engine. A chopper could also be downed, given the right circumstances, by anything from heavy automatic weapons to small arms. An injury to one or both pilots was very possibly an end-of-life calamity. Damage to one rotor would make the chopper uncontrollable. If the Jesus nut was shot off, both rotors would be lost and the Huey would drop like a rock. If a single round clipped the cable that drove the tail rotor, the unopposed torque of the lift rotors caused the fuselage to spin like a top, faster and faster, and the chopper hit the ground like a carnival ride run amuck. Victor Charlie, secluded in his jungle hideaway, listened to the rotors and plotted direction and distance and kept in touch with comrades. Our chopper had been on the same azimuth for fifteen minutes. Our departure point had been C-2, Special Forces headquarters for all the teams in II Corps. The VC could lay a ruler on a map. We were either headed for Phnom Penh, capital of Cambodia—out of the question—or Duc Co! The dinks weren’t stupid. We were targeted. Dread was my constant companion, especially at night. Over the length of my tour, fatigue warped dread into doggedness.

The headset squawked as the pilot made contact with A-215 at Duc Co. The pilot had found these few acres of sovereign Special Forces territory. A friendly needle in a hostile haystack. It may have been routine to them, but it amazed me. But then, he couldn’t insert a chest tube. The gunners slid open the hatches and the cold, damp wind sent a chill through me. They racked their M60s as the pilot initiated his descent. A misty rain engulfed us. My heart pounded, knowing we were corkscrewing between mountain peaks. The camp, with several generator-powered lights, became visible—a few sandbagged buildings, berms, bunkers, and trenches, all hacked out of the jungle. Even from the air it looked primitive and dangerous. Isolated. Vulnerable.

Lights flashed on to identify the LZ, and the Huey veered toward the chopper pad. The rotors whipped up muck as the pilot settled in. He shut down the engine to wait for us, and the pad went dark. Y-Kre and I dropped to the rain-soaked ground and were met by the team medic. He wore a tiger suit. No rank. No insignia. No name tag. Typical of many Special Forces troopers, in an effort to bond with the Montagnards, he had added native gear to his uniform. A strip of Montagnard loincloth was looped at his neck; a bone amulet hung at his chest. Brass bracelets dangled from his wrists. The troopers respected tribal customs, ate tribal food, studied local dialects, and participated in various Montagnard rituals. Their unique mission and isolation challenged them to live on the edge, and they developed a lifestyle that went with it.

Bill Patch, the light colonel who commanded the Special Forces detachments in II Corps, tolerated the slack comportment. He referred to his men as “the best of the best.” He understood them—individualistic, unconventional, and iconoclastic—and what happened to them in the bush. Patch also understood that regular line officers at Military Assistance Command-Vietnam (for the most part) neither understood nor supported the Special Forces mission. Beyond their congenital distaste for elite troops, the Special Forces way of life was guaranteed to annoy the most sympathetic. “Sometimes,” Patch admitted, “the guys go a little native. But they do a helluva job. It’s hard, dirty, and bloody. They work their asses off. The bastards are only one, determined assault from being overrun.”

Y-Kre and I followed the medic through the camp. A-Team compounds were like nothing else on earth. Designed to be defended against overwhelming odds, the sandbagged, concertina-wired, zigzagged-trench perimeter overlooked cleared fields of fire rigged with tanglefoot barbed wire, command-detonated Claymores, trip mines, foo-gas, and detonating cord. Bunkers with interlocking machine guns anchored this killing zone. Communications trenches connected to inner defensive positions, should the perimeter be breached. Pre-sighted mortars were dug into deep pits in the center of the compound. As many as seven or eight languages and dialects were spoken within a single camp. This polyglot mixture included not only American and Vietnamese Special Forces troopers, but also native laborers, mechanics, Bechtel civilian contractors, various Montagnard tribes, Nùngs, and Filipinos.

Nùngs were a warrior class of ethnic Chinese who had lived in Vietnam for centuries. They were hard-dying men who had a well-earned reputation as thoroughly tough killers and mercenaries. The Special Forces hired them as scouts, bodyguards, and ambushers. The Nùngs were also recruited to form a rapid reaction unit called the Mike Force, so-called for the letter “M” in the phonetic alphabet, which in this case stood for “mobile.” They were the highest-paid non-American troops in South Vietnam. Filipinos were often hired and trained by the Central Intelligence Agency and used routinely to staff its Asian operations. Their presence was a virtual declaration that if the place wasn’t actually owned by the CIA, the Company was definitely involved in the action.

This motley collection of characters inevitably included VC agents and sympathizers. There were victims and victimizers of all types: criminals, pimps, whores, petty thieves, murderers, psychotics, and poltroons. All were tough. Some were vicious. Camp regulations were the only law and had to be enforced by the A-Team commander and his men. A goodly number of native women inhabited the camps. Some were spouses, some were girlfriends, some were whores, some were VC, and some were refugees from the fighting in the area. Most were on the payroll in some capacity—maids, cooks, laborers, washer women, and cleanup details. The actual number of Montagnard soldiers was never more than a couple hundred. These isolated compounds were like daggers pointed at the throat of the VC and NVA, daring them to counter the threat.

The medic had placed the wounded Montagnard in the teamhouse. My jacket was soggy, and I dropped it over a couple of jerry cans. I renewed my acquaintance with Dick Johnson, the captain who commanded A-215. I met some troopers I didn’t know. One sat tilted back in a chair at a table, cigarette dangling from his mouth. “Doc, did you bring the mail?”

“No.” I reddened, realizing my blunder instantly. I should have stopped by the C-2 mail room to see if there was mail for their team. No standing order existed to get mail to isolated camps. But failure to seize any and every opportunity was inconsiderate. Careless indifference. Inexcusable. Almost unforgivable.

“Shit!” The chair dropped forward with a bang. The trooper furiously stubbed out his cigarette in the base of a hacksawed 155 shell-casing and stormed out. There was silence from the other men. No words of annoyance at my failure to pick up the mail. But no words to gloss over the rudeness of their teammate either. For that trooper—for all of them at that moment—a mailman was more important than anyone who showed up with two bars on his collar, even a doctor.

The wounded Montagnard was conscious. He had a small blue-black hole, just as the medic said, “right between the fuckin’ eyes.” I rolled him to one side. There was no exit wound. He responded cogently to my questions, as Y-Kre interpreted. I went over him quickly. He exhibited no gross neurological deficits. Vital signs were stable. What to do? Nothing, really. I started an IV and added antibiotics to the saline.

As I got the Montagnard on a stretcher, Dick Johnson told me I had a call from the C-Team. He led me to the commo bunker. The communications sergeant at C-2 reported that one of Herb Payne’s Nùngs had been gutshot on patrol. “Gimme the coordinates,” I said.

Johnson pushed a paper and pencil in front of me, and I jotted down the information. I pressed my lips against the mike. “Stand by. Over.”

“That’s a rog,” came a cheery singsong reply.

I handed the coordinates to Johnson and his top sergeant. They consulted a map in the dim, yellow light of a naked bulb. “It’s about twelve klicks from here,” Johnson said. “Probably just inside Cambodia.”

We went to the chopper, and Johnson and the pilot studied the map. After a moment, the pilot nodded.

“I’ll tell the C-Team,” Johnson said.

The pilot tightened his safety harness. “I’ll notify Holloway.”

We loaded the wounded Montagnard onto the chopper. A drizzly dawn broke as we pounded aloft. Y-Kre covered the Yard with an additional blanket, knelt close to his ear, and whispered in Rhade.

The Dust Off zeroed in on the coordinates. A short time later, we settled into a jungle clearing marked by yellow smoke. The wounded Nùng was piled aboard. Lifting off, a bullet beyond the clearing shattered the thigh of a door gunner. He pitched forward out of the chopper and hung suspended by his safety harness. The other gunner sprayed long deafening bursts of covering fire from his M60. Afraid the expanding catch-bag would jam his weapon, he tore it away. Smoking brass spewed into the air.

Y-Kre and I tried to haul the wounded gunner aboard by his safety harness, but he was dead weight. Perched at the open hatch, with the pitching chopper and the brass underfoot, I was afraid I would fall out. The pilot tried to set down, but every time he skimmed a clearing, we took ground fire. He set an azimuth for the C-Team.

I let the door gunner dangle and turned to the Nùng, probing his belly wound with a finger. It popped into his abdomen. Bleeding seemed minimal. Y-Kre applied a pressure dressing. The Nùng’s pulse was thready and weak. I started an IV and wrung in a unit of albumin, the olive-green aluminum container collapsing in my hands like newsprint. A plasma expander, albumin was a lousy substitute for blood, but the best I could do. I tossed aside the empty albumin packet and switched to Dextran, adding antibiotics to the infusion. The Nùng was muttering in Mandarin, but Y-Kre could communicate with him in Vietnamese. I sat back and watched the leg of the door gunner’s fatigues fill up with blood.

Sergeants Cope and Franklin, two of my senior medics, waited at the C-2 chopper pad. The pilot hovered as the medics, struggling against the rotor blast, cut the door gunner free from his harness. They looked at me and shook their heads. I told myself that it was a mortal wound from the instant he was hit. The pilot settled onto the perforated-steel plate. We off-loaded the Montagnard and Nùng.

I leaned back into the hatch and yelled at the pilot above the roar of the engine. “Do you want me to get your gunner to Graves’?”

“We’ll do it!”

I motioned to my medics, waiting at the edge of the chopper pad. They returned with the body—a soggy mess of flak vest, jungle fatigues, and clotted blood. Y-Kre and I stretched him out on the deck of the chopper. I removed one of his dog tags, pried open his jaw, and placed the tag on his swollen tongue. I taped his mouth shut with army-green tape, and we carefully wrapped his body in an army blanket, making certain it was neat and in good order, with edges folded and tucked. I couldn’t look the chopper crew in the face. Y-Kre and I dropped to the ground. We watched the Huey lift off in tender inches and gently swivel east toward Camp Holloway.

I brought my hand slowly to my forehead in salute as the chopper gained altitude.

Y-Kre studied my face. With his limited medical knowledge and his absolute faith in me, he said, “You did all.

TWO

Letter from a Ghost

January 1997

The letter came to my home in Flagstaff, Arizona, where my family and I had moved in 1971 after I completed a dermatology residency. I handled the slightly soiled envelope warily, noting postage from the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. I went upstairs for privacy, feeling the weight of the envelope. I dawdled… Finally, carefully, I opened it. The letter was in ballpoint on lined notebook paper.

January, 1997

Boun-M’Bon

Dac Lac Province, Vietnam

My Dear Brother Lanny Hunter,

I always remember my brother Lanny Hunter and hope that you still remember me. You brought me to the Lake Biên Hòa to be baptized in the name of Jesus Christ. You and I worked together at Detachment C-2 Camp in Pleiku. During that period I actively worked for the US Green Beret Commando Airborne Force. Maybe you can recall it.

During my employment with you, you did give me some good advices. I should thank you. For the present time, I am in poor miserable conditions. Thus, if you feel some sympathy for me and have a kind concern for me, please help me.

I was detained in the reeducation camp from 1975 to 1985 at Camp Number Three located in Tân Kỳ District, Nghệ Tỉnh province. My family is very poor now, brother. Lack of everythings. But my wife and eight children still steadfast trusting to our Lord. I myself still firmly believe in God by the name of Jesus Christ my Savior. Continue pray for me and my family that may God help me to have more understanding in God’s word and live completely correct according to the guide of the Christians in New Testament.

The government isn’t yet allow us to develop the Church of Christ and do not give us certificate. I still try my best to serve the Lord. We study Bible in the family, house to house together. I continue to preach from house to house. I spend my own money to go back and forth from my village to Buôn Mê Thuột to mobilize our Christians there.

My love to you, brother,

Y-Kre Mlo

I clutched Y-Kre’s letter in my hand, sinking into a hollow self. I went downstairs and slipped out onto the deck. Sat down. Put my head between my knees. Took deep, slow breaths. It was dry season now in Vietnam’s Central Highlands. In northern Arizona, it was winter. Four inches of snow extended to a western ridge, the expanse broken by rock outcroppings and scattered ponderosa pines. The San Francisco Peaks, sacred mountains of the Navajo and Hopi, soared above the Colorado Plateau. The low-hanging sun yielded some warmth as it torched the underbellies of clouds. Reflection from the snow turned the landscape red. Vietnam, three decades before and ten thousand miles distant, but always with me in bits and pieces, came back with a vengeance.

I reread Y-Kre’s letter. His tortuously scrawled words, like fiery pokers, rekindled embers buried in the ash heap of my memories. The setting sun flamed out. A chill settled over the plateau, doubly penetrating because of Y-Kre’s bleak letter. I shivered. A frost formed on my soul as I returned to my study and a crackling cedar fire.

THREE

Mǫi

I tried to imagine Y-Kre, now in his midforties, after ten years in the grip of his communist captors. I met him on my first day at Detachment C-2, a relatively recent Montagnard recruit for the Strike Force. He was fifteen or sixteen years old—a man by Montagnard standards. He stood about five and a half feet tall, with skin the color of creamed coffee and thick black hair. He had a ready smile. Quiet, soft-spoken, polite, handsome, and winsome, he had acquired the habit of shaking hands and did so at every opportunity. He had been trained as a medic, but his real value lay in his language skills. He spoke not only a dozen Montagnard dialects, but also Vietnamese, French, and enough English to be better at it than anyone else around. His syntax was muddled, but he had a remarkable vocabulary. He once showed me a vocabulary list he was studying: oppression, downtrodden, persecution, intervention, punished, hellno, fuckyes, and shitstorm. With Y-Kre at my side, I could communicate with almost anyone who materialized out of the highland haze, although occasionally he would say, “Not understand, Doc.”

The Montagnards evolved as a distinct, ethnic culture from aboriginal, Mon-Khmer, and Malay-Polynesian peoples. They were self-sufficient, hardy, intelligent, primitive, superstitious, and fiercely proud, and had preserved their culture almost undiluted into the modern era. The millennia had passed them by, and they lived in isolated villages scattered throughout the highlands that crossed the borders between Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia.

The word Montagnard is a French term meaning “people of the mountain.” There were about forty tribes; among them were the Rhade, Jarai, Bahnar, Koho, Mnong, and Stieng, speaking almost as many dialects. They inhabited thatch-roofed huts of bamboo raised on stilts. Pigs and chickens were penned beneath the huts. A communal longhouse occupied the center of each village. Larger than all other structures, its soaring, steeply pitched, thatched roof was shaped like the blade of an ax to symbolize strength. The size of the longhouse, in comparison to those in surrounding villages, demonstrated the village’s prosperity. All matters of importance for village life took place there. It served as a school for teaching tribal customs. Even though Montagnard society is matriarchal, only males could enter the communal longhouse. Adolescent boys could stay there until they married, as could adult widowers.

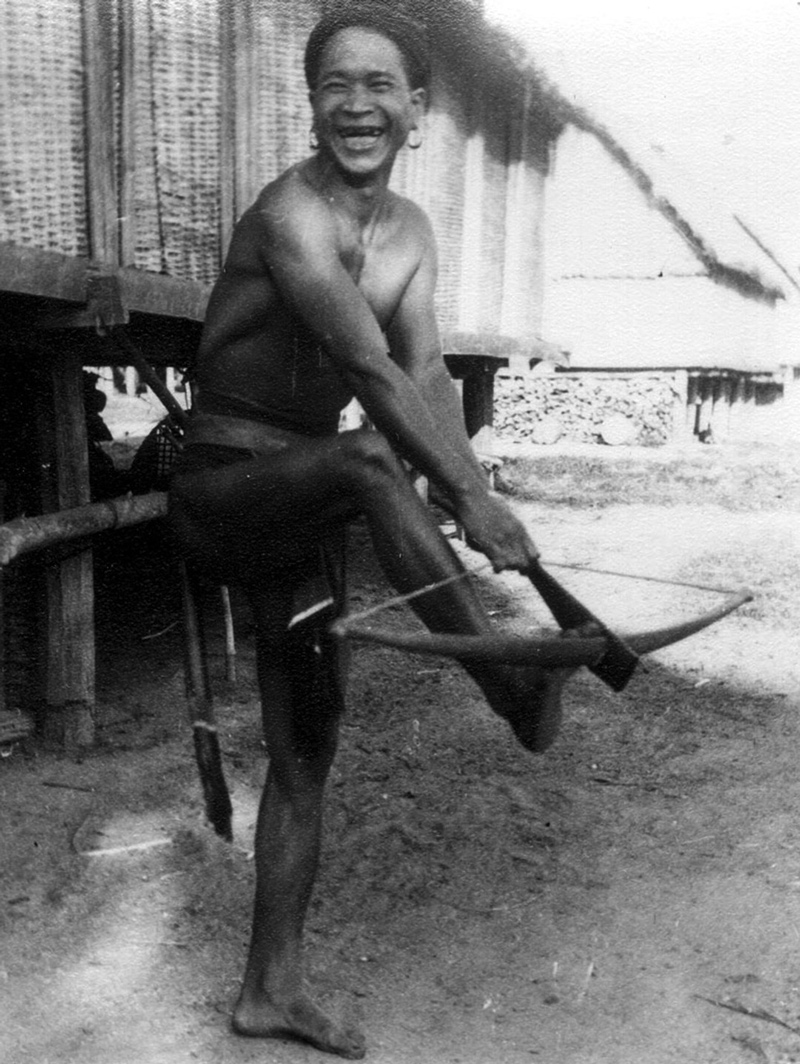

Montagnards lived by slash-and-burn farming. They augmented their diet with wild fruits, plants, roots, lizards, snakes, dogs, and rats. They raised their own tobacco. They crafted crossbows, arrows, knives, and spears. Large game was brought down with arrows tipped in poison extracted from a jungle plant. Skill with a shuttle and loom created coarse cloth for loincloths, robes, and blankets. Bracelets and other jewelry were fabricated from brass. Their brew of choice was rice wine, concocted by fermenting rice in large clay crocks. The mash was layered with bamboo leaves and topped off with water. Bamboo straws were thrust to the bottom of the crock to suck water through the mash, the leaves filtering out the largest particulate matter.

The Vietnamese regarded the Montagnards as mǫi (savage). They had both repressed and neglected the Montagnards for twenty centuries. Discrimination was institutionalized. For their part, the Montagnards wished to be left alone. They had well-established intertribal connections, and their longing for independence was an open secret.

Montagnard villager in the Central Highlands, 1965. Source: Author’s personal file, 1965.

The CIA conceived the idea of arming the Montagnards in 1960. They hoped to persuade the tribes to join the cause of South Vietnam and provide a military threat to the VC and NVA infiltrating the Central Highlands. The effort was in full swing by 1963. In executing this program, thousands of Montagnards were catapulted into the twentieth century. Recruits were taken out of their loincloths and outfitted in tiger suits. Jungle boots were placed on thickly calloused feet. They exchanged their crossbows for carbines and their spears for grenades. They were trained in marksmanship, patrolling, squad maneuver, fire discipline, and rapid response drill. Some were trained to operate crew-served weapons. Others served as radio operators, medics, and interpreters. Montagnard units were officially designated the Civilian Irregular Defense Group, or CIDG. They were placed under the command of the Special Forces.

The Special Forces referred to the tribes as Yards, but it was a term of affection, not a pejorative. We called the CIDG the Strike Force and referred to individual troopers as Strikers. We were a good fit. The Yards tended to like Caucasians, harking back to days when French colonials offered them protection from the Vietnamese. When I and my Special Forces comrades lived and worked among the Montagnards, it was clear they despised the condescending Vietnamese.

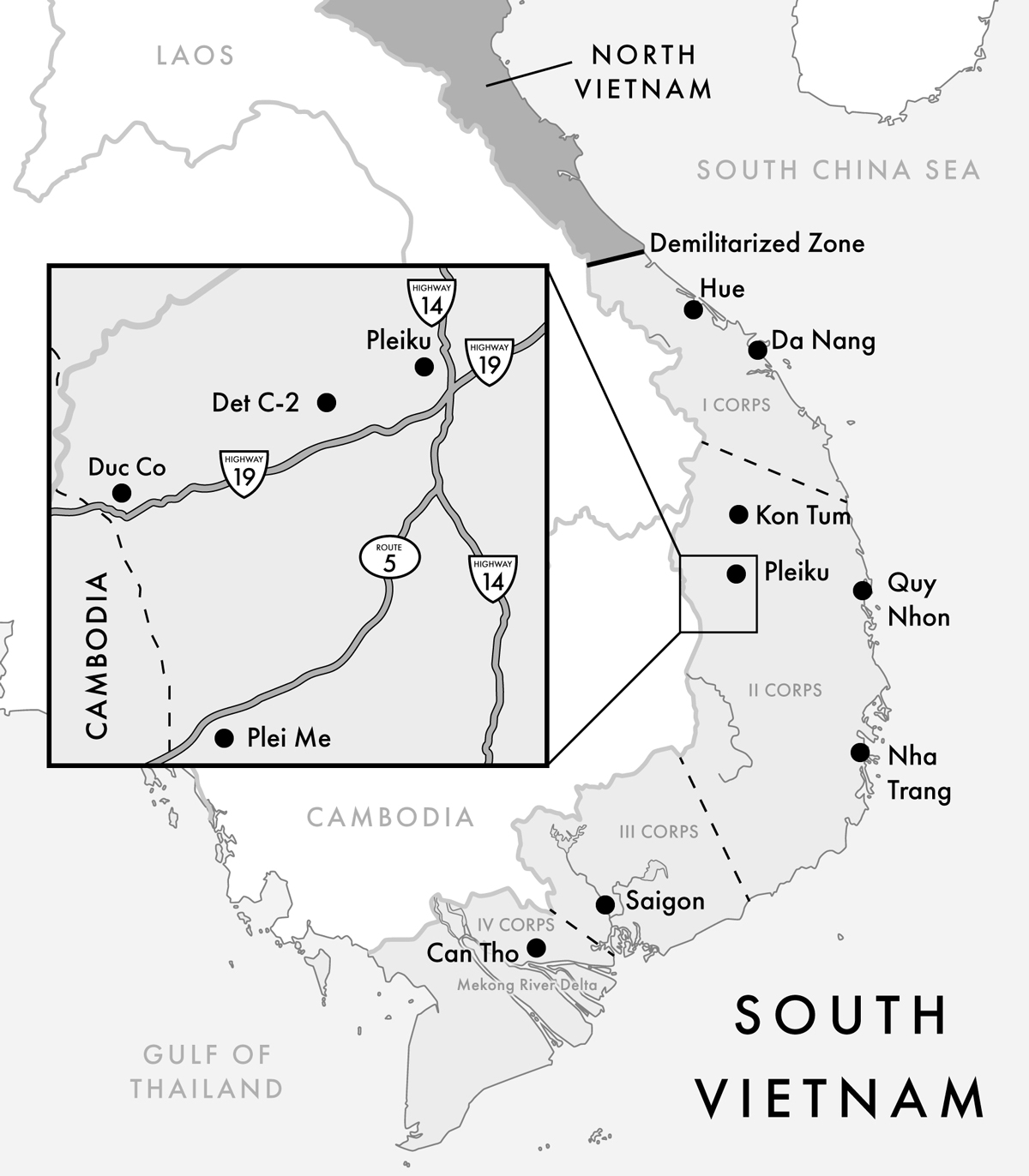

Detachment C-2, my duty assignment when I arrived in-country in July 1965, was in the middle of Pleiku province. It was some fifteen kilometers west of the province capital, Pleiku City, and thirty-five kilometers from South Vietnam’s border with Cambodia and Laos. Those borders were clearly delineated on a map. For boots on the ground, there were no visible geographic distinctions. It was all a blurred, bloody battlefield. The twelve-man A-Teams under C-2 command were strategically scattered along the Cambodian and Laotian frontiers.

Tactical Map, South Vietnam, 1965/66. Map designed by Larissa Ezell.

C-2 consisted of about thirty troopers garrisoned in a sandbagged, bunkered, rectangular compound about the size of a football field. I stepped off the Huey that ferried me in and eyed a hand-painted, wooden sign that arched over the gate: Bù Lại Sự Tổn Thắt Là Kiểm Soát Được Những Vùng Hẻo Lánh. The translation underneath read, The Risk of Loss Is Worth Control of Remote Areas. In 1965, that didn’t feel like bravado.

I walked into the compound, suitcase and M16 in hand, challenged by armed Nùngs. I met my commander, Bill Patch, and was rapidly absorbed into my duties, which included two almost incomprehensible realities: the Montagnards and the Montagnard Hospital. My personal introduction to the Montagnards and their culture was Y-Kre Mlo. He was Rhade. In the Rhade language, gender was always incorporated into the name. “Y” meant mister and preceded all male names. His first name was pronounced ee-cray. Literally translated, it was Mister Kre. It was as if I were always called Mister Lanny. Very quaint. Very useful.

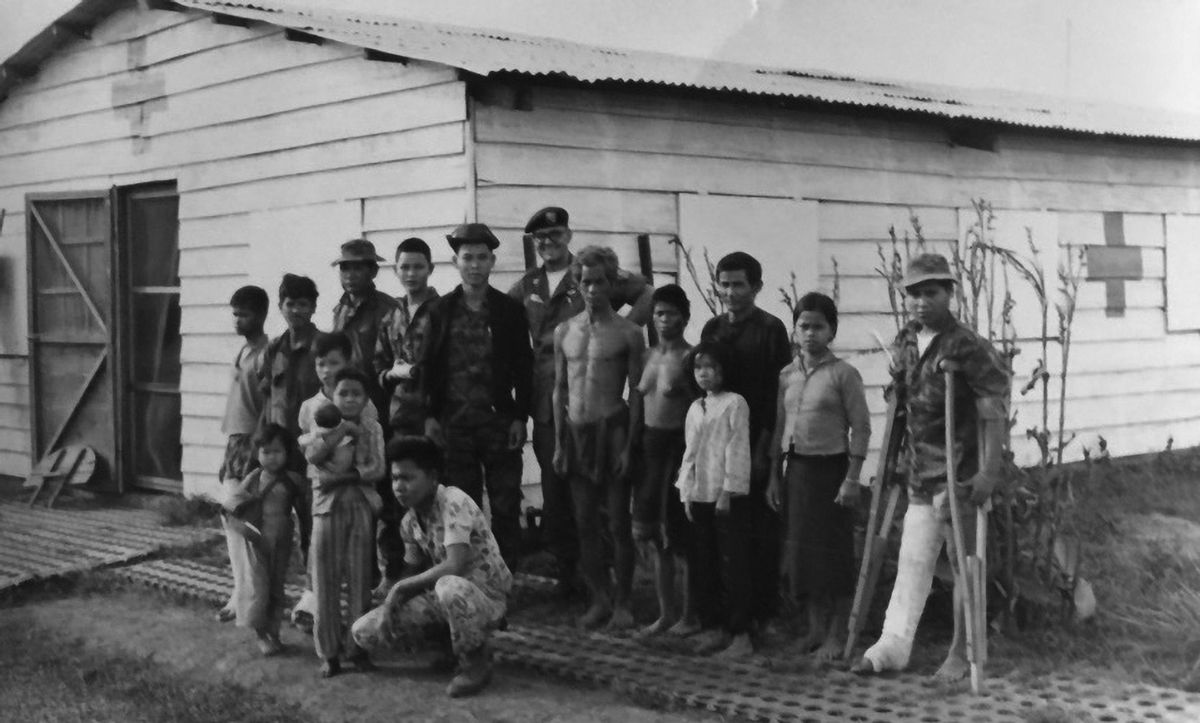

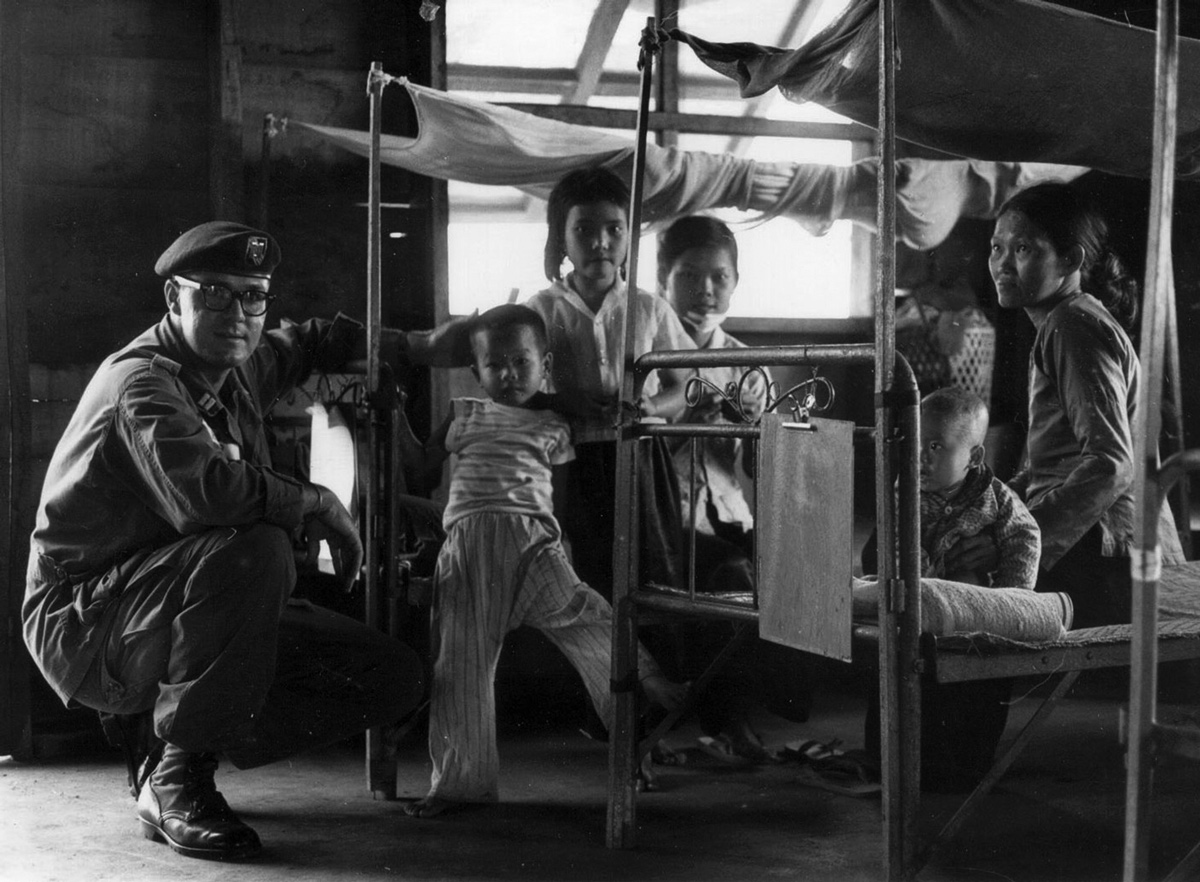

Capt. Lanny Hunter with Y-Kre Mlo, Detachment C-2, South Vietnam, July 1965. Source: Author’s personal file, 1965.

Y-Kre quickly became indispensable to me in the performance of my duties. A crude hospital for wounded CIDG soldiers was established at Detachment C-2, as they were generally discriminated against at Vietnamese hospitals because of their ethnicity. Two small wood-frame, whitewashed buildings, identified with red crosses, were constructed outside the C-Team compound. This meant, of course, they were outside the perimeter and unprotected—a particular concern at night. Emergency care and procedures were done in the C-Team dispensary, which had a small surgical unit, field X-ray machine, and medical laboratory. Convalescent care was done within the hospital buildings. Each building had about twenty metal cots. Wood-fired stoves provided a source of heat and a cooking surface. Patients (and their families) cooked and cleaned.

Capt. Lanny Hunter with patients and family members at Montagnard Hospital, Det. C-2, 1965. Source: Author’s personal file, 1965.

Y-Kre essentially administered the Montagnard Hospital. He was my medical right hand and my alter ego. With my medicine and his language, the word went out that at C-2 there was medical care, food, clothing, compassion, protection, enthusiasm, and optimism. We could be trusted. The little hospital became a magnet for all Montagnards, not just battle casualties. It was a given that VC were among my patients. The wounded streamed in. Gunshot wounds, frag wounds, mines, booby traps, punji stakes, burns, and knife slashes.

I was also confronted by the sick, the weak, the maimed, the ruined, the orphaned, and the lost. I took care of abrasions, fractures, monkey bites, snake bites, and water buffalo gorings. I treated fungal infections, pneumonia, diarrheal illness, lice, liver failure, leprosy, plague, dengue fever, malaria, typhoid, encephalitis, tapeworm, hookworm, schistosomiasis, and scabies. There were illnesses whose etiology I could only guess at—or hadn’t a clue—and which I had no way of properly treating. There were old women with teeth stained by betel leaves and areca nuts, commonly used as mild stimulants. There were babies, sick or defective, starting the arduous journey of their lives with little hope and even less advantage. There were big-eyed children whose stoicism in the face of the war and its ravages could tear your heart out.

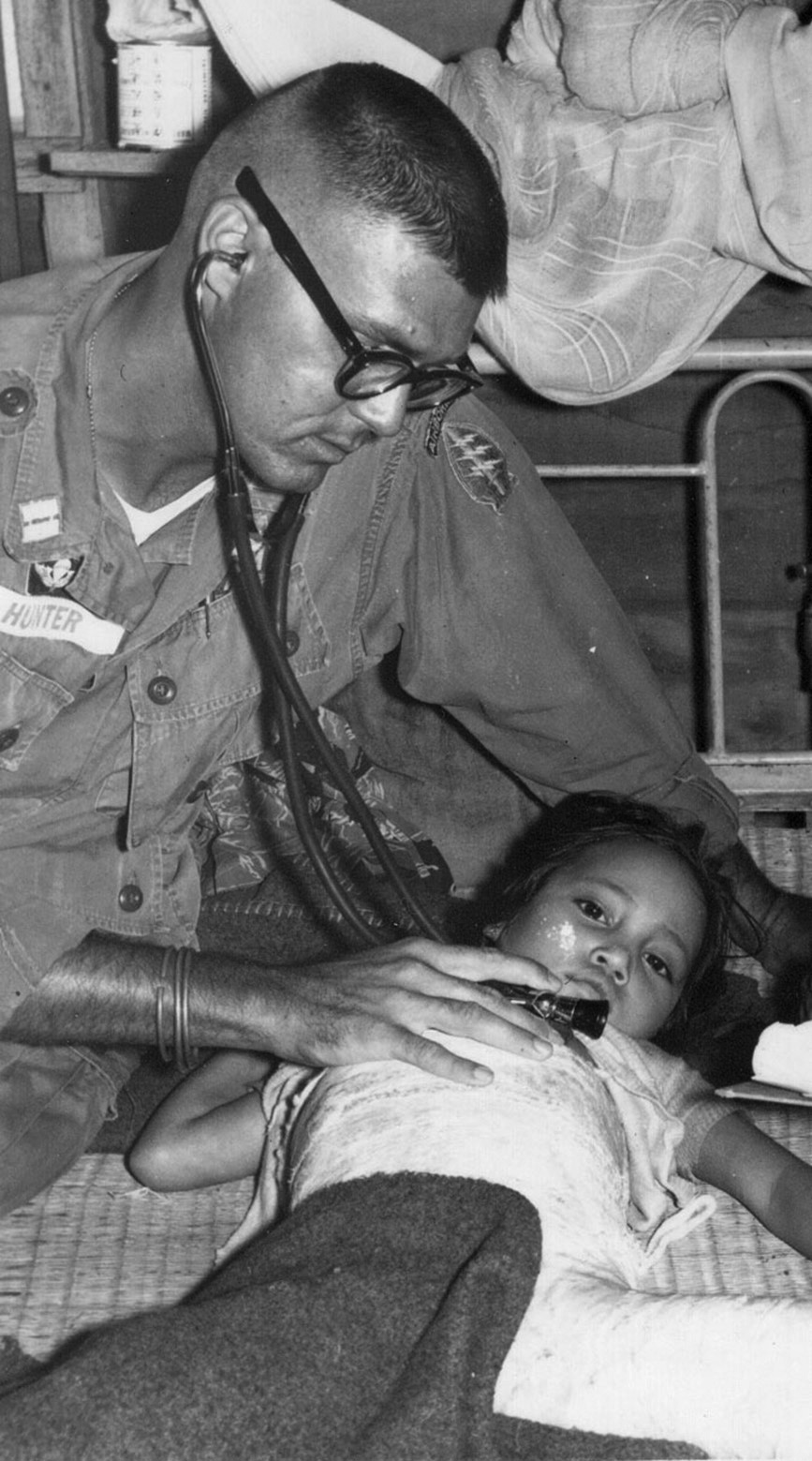

Capt. Lanny Hunter at Montagnard Hospital, Det. C-2, with patients and family, 1965. Source: Author’s personal file, 1965.

Y-Kre shared my risks. He never refused to climb on a chopper or go on a mission—no matter how cockeyed. I became his mentor in the English language, Western culture, medicine, American policy, and finally religion. He informed me about the world of the Montagnards, their yearnings for independence, and his own ambitions. He was my comrade-in-arms, a passable medic, and my interpreter. Above all, Y-Kre knew the Central Highlands. If we had to go to ground, he knew where. Over time, he became a friend and protégé. He also became my Christian brother.

Capt. Lanny Hunter with Montagnard girl in spica cast for hip injury, Montagnard Hospital, Det. C-2, 1965. Source: Author’s personal file, 1965.

The dying cedar coals in my study in Flagstaff left me lost in thought. I concluded, knowing it would quicken a troubled past, that I must help Y-Kre. Poor, brave, tragic Y-Kre. Help him? The last time I helped him I set him on the path that produced this terrible letter. Perhaps the best way to help Y-Kre was to stay out of his life. I was ignorant of the current political situation in the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Perhaps even a letter from me, let alone other assistance, would place him in danger once again. But, I could only take him at his word. Thus, if you feel some sympathy for me and have a kind concern for me, please help me.

The United States government made policy in Vietnam, both the getting in and the getting out. America held the marker for South Vietnam. But I held the marker for Y-Kre Mlo. Maybe I could help him. Maybe not. But I knew I had to try. If he had the courage to persevere, I must at least try to meet him on his journey. I had to go back.

Ambiguity is a motherfucker.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR — Lanny Hunter is one of the most highly decorated medical officers of the Vietnam War, having been awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, Bronze Star-V, the Air Medal, Purple Heart, Combat Medical Badge, and the Vietnamese Gallantry Cross with Gold Star. He has lectured in medical, military, educational, civil, and church venues. Hunter has written several works, including Living Dogs and Dead Lions, My Soul to Keep, and Stories of Desire and Narratives of Faith. He lives with his wife, Carolyn, in Denver, Colorado.

Leave A Comment