Ambassador William E. Colby

By Lewis Sorley

Excerpted from Indochina in the Year of the Dog—1970, pages 77–86, with permission.

William E. Colby (CIA)

William Egan Colby was born into an Army family in 1920. He got off to a good start (when his father was stationed in China) at a school whose motto was: “Tientsin Grammar School, fight we must, or Tientsin Grammar School, bite the dust.”

Colby graduated from Princeton, served in the OSS during World War II (parachuting into German-held France and Norway to assist partisans), graduated from Columbia University Law School after the war, then soon joined the newly-established CIA. Early postings in Italy and Sweden were followed by assignment to Vietnam, where he served as Deputy Station Chief, then Chief of Station, Saigon, during 1959-1962. He then became Chief of CIA’s Far East Division before returning to Vietnam to soon become Deputy to the Commander, US Military Assistance Command, for CORDS (Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development Support).1 That meant he was, with the rank of ambassador, in charge of U.S. support for South Vietnam’s pacification program.

The COMUSACV then was General Creighton Abrams. Colby took over his new job from Robert Komer, who had been sacked by Abrams.

What they set about to prosecute was what they called “One War,” meaning not a war of “the big battalions,” as people had referred to the combat operations in the earlier years, contrasting them to an “other war” of pacification and so on. They said combat operations, pacification, and improvement of South Vietnam’s armed forces were all equally important, and all had to progress together, or if not then the overall enterprise was not going to succeed.

As a consequence, the measure of merit changed dramatically from the “body count” of the Westmoreland years to “population secured.” And the “search and destroy” tactics prescribed by Westmoreland were now changed to “clear and hold” tactics, with the “hold” being provided increasingly by the South Vietnamese, and especially their Territorial Forces (Regional Forces and Popular Forces), as U.S. troops were progressively withdrawn.

With Colby’s ascent to the top post in pacification support, the remarkable triumvirate of Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker, General Abrams, and Colby—men of like character, integrity, devotion to duty, and personal modesty—was in place and managing American forces and actions in Vietnam to good effect.

Abrams and Colby quickly established a bond of mutual trust and confidence. “Shortly after Komer left,” Colby remembered, “Abrams drew me aside. ‘You know, I think our relationship is going to be a good one,’ he told me. ‘I’ll make sure it is, General,’ I responded.” And, added Colby, “I was enormously impressed by his grasp of the political significance of the pacification program. Finally we had focused on the real war.”2

Unlike his predecessor, who stuck close to his Saigon villa, Colby was out and about. General William Rosson, then the Deputy Commander to Abrams, liked what he saw in Colby, a man who “was soft-spoken and—unlike Komer—spent a lot of his time in the field, so he didn’t have to rely on reports and knew what was going on.”3

“My evaluation of how strong the infrastructure was, and how strong the enemy was,” Colby confirmed, “was more learned by my frequent visits to the countryside and driving up the roads…than by reading the numbers in Saigon.”4

Ambassador Bunker, too, welcomed Colby’s appointment, citing “his ability to get things done, also his judgment, his analytical powers…his experience.”5 Said a colleague, contrasting the new man with his predecessor, “Komer was always trying to convince you pacification was working, but Colby was trying to make it work.”6 Noted a reporter, “Colby’s recipe for good conversation has two ingredients—his questions and your answers.”

That had followed on an introductory briefing on the pacification program as Colby characterized it soon after becoming Deputy to the COMUSMACV for CORDS. Said General Abrams at a subsequent staff meeting: “I think that [Colby’s briefing] was a splendid presentation. I think it comes out at a most opportune moment.”7

In early July 1968 Abrams had described the ultimate objective at a weekly staff meeting: “I think we probably all agree,” he said, “that in the end what they’ve [the South Vietnamese government] got to get done here is control of their own people and get them secure. The pacification effort is the ultimate effort which has to be made.”8

Later Colby recorded his admiration for Abrams and his grasp of the war and how it should be fought. “It wasn’t until…1968 that we really began to make progress in the real nature of the war there,” he observed. “The intervening years were just confusion and chaos.”

In the aftermath of Tet 1968 Colby was the architect of an Accelerated Pacification Campaign designed to restore the damage done by Tet in the countryside and take advantage of the more favorable situation existing there as a result of the enemy’s severe guerrilla force losses at Tet, but in an abrupt break with earlier practice the plan was not just foisted on the Vietnamese. Rather they were led to develop a viable plan of their own, an approach that gave them a much greater stake in the outcome.

Even John Paul Vann, a professional skeptic, was favorably impressed by the resulting plan. “I greatly endorse the direction that this presentation suggests that we go, and greatly applaud the effort that’s gone into recognizing the basic problems that have got to be countered,” he told Abrams and the other commanders.9

In late September 1968 Abrams assembled his commanders for an analysis of the broader implications of the war. The heart of the briefing was presented by Colby, who described an ominous current situation, one that saw the enemy trying to establish “Liberation Committees” throughout South Vietnam with what he called a “particular sense of urgency.” At this point the Hamlet Evaluation System (a periodic statistical compilation designed to reflect the current status of pacification), while admittedly imprecise, suggested that more than 46 percent of the population was under some degree of Viet Cong influence. Thus, said Colby, “in the event of a cease-fire, the enemy might claim political control of about one-half of the population of South Vietnam.”

Colby then turned to means of reversing this unsatisfactory situation. The Accelerated Pacification Campaign—of which he was the architect, although he did not say so—would seek to eliminate enemy base areas and the command centers of his political effort. A program called Phuong Hoang—known as Phoenix in English and designed to neutralize the Viet Cong infrastructure—would serve as “an essential tool for this action.” A preemptive campaign would be targeted against those areas controlled by the Viet Cong, contested, or heavily infested by VC; its objective was to plant the government’s flag, saturate the areas with military forces, and purge the enemy’s underground shadow government. Territorial security, VCI [Viet Cong Infrastructure] neutralization, and supporting programs of self-help, self-defense, and self-government would thus constitute the counteroffensive.

This was, Colby made clear, a job for the Vietnamese, but one in which American forces could help by screening the pacification areas from enemy assaults and conducting spoiling operations against enemy forces. Phoenix was described by Colby as “a program of consolidating intelligence and exploitation efforts against these particularly key individuals [in the communist infrastructure].” It finally got off the ground, he said, in July 1968 when President Thieu signed a decree.

Having spent the past several months developing his approach, Colby now addressed his presentation most directly to Abrams. “I was not disappointed,” he said later. Abrams “listened intently, following each point with obvious understanding of the essentially political analysis I was giving.” At the end Abrams gave his full approval. When the Accelerated Pacification Campaign began on November 1, 1968, Abrams considered it the turning point at which the government “took the initiative in South Vietnam, the initiative in the larger sense of the total war.”

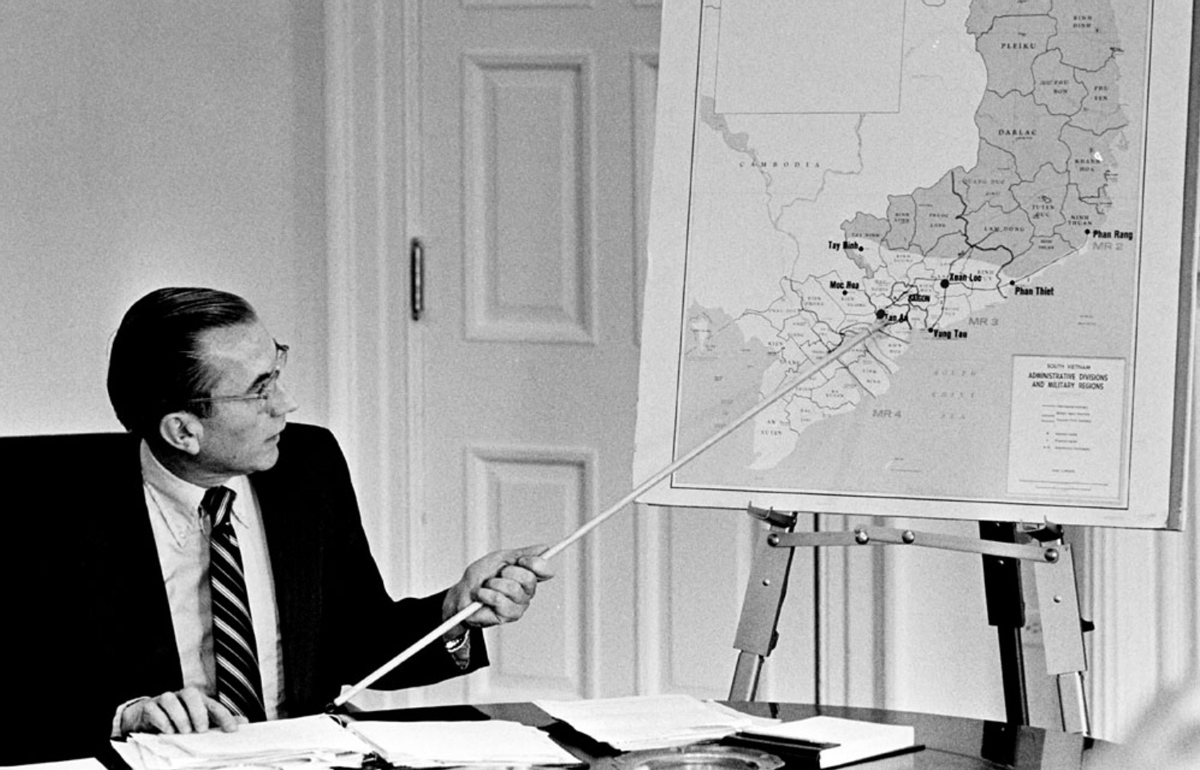

CIA Director William Colby points out Communist advances in Xuan Loc on a map of Vietnam in the Cabinet Room at the White House during a meeting of the NSC regarding the Communist advances in S. Vietnam, Washington, D.C., April 9, 1975. (CIA)

As 1968 neared an end, with the Accelerated Pacification Campaign designed by Colby roaring along, Abrams gave Colby some well-deserved recognition, saying at the weekly senior staff meeting that “this pacification program really bears no resemblance to what was going on last year—as far as results and so on.” And Abrams viewed this as the critical battlefield, cabling Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Earle Wheeler that in pacification “we are making our major effort; so is the enemy. In my judgment, what is required now is all out with all we have. The military machine runs best at full throttle. That’s about where we have it and where I intend to keep it.”

In mid-January 1969 Colby returned the compliment, telling a visiting Ambassador U. Alexis Johnson that “the main point is, as General Abrams tells us, it’s one war. You know, we used to talk about the ‘other’ war, but he’s made it into one war. I think the full strategy here is all of one piece. Pacification is very much a part of the considerations of the regular divisional units.” And, he added at the next staff meeting, “We’ve put the major emphasis over on the RF and PF [the South Vietnamese Regional Forces and Popular Forces].”

Colby identified South Vietnam’s Regional Forces and Popular Forces—components of the Territorial Forces whose mission was to remain in place in their home provinces and districts to provide local security—as key to gains in pacification. General Abrams had made their expansion and improvement his special concern, arranging that they get the modern weapons and other equipment that General Westmoreland had for so long denied them and sending out small military advisory teams to work with the RF companies and PF platoons.

Greatly expanded during these later years, Regional and Popular Forces eventually came to comprise half of South Vietnam’s total armed forces nationwide. “Gradually, in their outlook, deportment, and combat performance,” said Lieutenant General Ngo Quang Truong, “the RF and PF troopers shed their paramilitary origins and increasingly became full-fledged soldiers.” So decidedly was this the case, Truong concluded, that “throughout the major period of the Vietnam conflict” the RF and PF were “aptly regarded as the mainstay of the war machinery.”10

Colby was, as were Ambassador Bunker and General Abrams, very admiring of how President Thieu was pushing pacification in all its manifestations. At a staff meeting in early February 1969 he described how during the past week Thieu had gone to each of the corps areas to review in depth what had been accomplished during 1968 and the plans for 1969. The President said he wanted to maintain the momentum, reported Colby, and put his major emphasis on early elections in all the villages in order to meet the VC liberation committee challenge. Plus, he “explained in some depth that he wanted the people of the country involved in the war by being invited to participate in their own decision making. He kept pounding this in on the various province and district chiefs, that they were not just to boss the people around, that they were to let the people make decisions and get involved in the whole problem.”11

An important initiative in identifying and neutralizing the enemy’s covert infrastructure that was keeping the rural populace under control through terror and coercion was the Phoenix program.

General Abrams often stated his belief in the great value of good intelligence. Colby shared that outlook, and it was at the heart of the Phoenix program. “This was an attempt to regularize the intelligence coverage,” he emphasized, “decent interrogations, decent record-keeping, evidence, all that sort of thing, the whole structure of the struggle against the secret apparatus. This was Phoenix.”12

Critics of the war sought to characterize the Phoenix program as an assassination scheme. Colby stoutly insisted otherwise, including in testimony before Congressional committees. For one thing, enemy who had knowledge of the enemy infrastructure and its functioning were invaluable intelligence assets. The incentive was to capture them alive and exploit that knowledge, not bring in mute corpses. When Congressional committees sent their own investigators to Vietnam, they found confirmation of what Colby had told them. Of some 15,000 VCI [Viet Cong infrastructure] neutralized during 1968, 15 percent had been killed (many in conventional combat actions), 13 percent had rallied (come over to the government side), and 72 percent were captured.13

Colby and John Paul Vann celebrated Tet 1971 by driving across the Delta, from Can Tho to Cau Doc, unescorted, just the two of them on a couple of motorcycles. Vann was by that point, noted Colby, very satisfied with the success achieved in the pacification program, “even to the extent of keeping his mouth shut once in a while, which was an extreme sacrifice for John.” The progress that had been achieved led Ambassador Bunker to observe, in a reporting cable to the President, that “pacification, like golf, becomes more difficult to improve the better it gets.”

In the autumn of 1971 Tom Barnes returned to Vietnam in the pacification program after an absence of three years. He told General Weyand, then the Deputy COMUSMACV, that he was struck by rural prosperity he found then, by the way the Territorial Forces had taken hold, and by the growing political and economic autonomy of the villages. “One of our greatest contributions to pacification,” he said, “has been the reestablishment of the village in its historic Vietnamese role of relative independence and self-sufficiency.”

These developments were not lost on the enemy, as revealed in a captured COSVN [Central Office for South Vietnam, an important enemy headquarters] Directive of October 1971. “During the past two years,” it read, “the U.S. and puppet [meaning South Vietnamese] focused their efforts on pacifying and encroaching upon rural areas, using the most barbarous schemes. They strengthened puppet forces, consolidated the puppet government, and established an outpost network and espionage and People’s Self-Defense Force organizations in many hamlets and villages. They provided more technical equipment for, and increased the mobility of, puppet forces, established blocking lines, and created a new defensive and oppressive system in densely populated rural areas. As a result, they caused many difficulties to and inflicted losses on friendly [Communist] forces.”14 That was a pretty good report card.

Colby, in sharp contrast to his predecessor Komer, proved insightful regarding military aspects of the war. When possible incursions into Cambodia were under consideration, Colby spoke up in support, emphasizing the importance of the enemy’s base areas and lines of communications across South Vietnam’s borders. “That’s the interminable part of this war,” he observed. “Unless you can solve that, you are here forever.” Abrams agreed. “No amount of bombing in North Vietnam is going to cause him to rethink his problem. But if we go in those base areas, he’s got to rethink the whole damn problem!”15

Additional confirmation of what had been accomplished by the South Vietnamese during the Bunker-Abrams-Colby years came from the enemy side. General Tran Van Tra admitted, as quoted in Olivier Todd’s splendid book Cruel April, that by the time of the cease-fire “our cadres and men were exhausted.” “All our units were in disarray, and we were suffering from a lack of manpower and a shortage of food and ammunition. So it was hard to stand up under enemy attacks. Sometimes we had to withdraw to let the enemy retake control of the population.”

Colby left Vietnam in June of 1971, drawn away by a family crisis. In 1973 he was appointed Director of Central Intelligence, a post he held for the next three years in one of the most difficult and contentious periods of CIA’s existence. Deciding that the Agency’s future viability depended on reestablishing its credibility with the Congress, he shared with its oversight and investigating committees the most damaging evidence of past misdeeds from institutional files. That earned him the enmity of some old hands—including, of course, those involved in the wrongdoing—but the admiration and approval of others.

“To say the very least,” wrote Colby in a 1978 memoir entitled Honorable Men: My Life in the CIA, “most of the White House staff and, for that matter, much of the intelligence community, were unenthusiastic about what I was doing. Their preferred approach, bluntly put, would have been to stonewall, to disclose as little as they could get away with, and to cry havoc to the national security about what they couldn’t deny—in short, the exact opposite of mine.”16 The book’s jacket described its author as “one of the most controversial and visible of CIA Directors.”

Colby may have been troubled by his dilemma, but he had no doubt of the correct course of action. “By cooperating, by being as forthcoming as possible, we did get the chance to present the CIA’s case in the most favorable light, place its few abuses in the context of its greater accomplishments, minimize the sensationalism and so protect the Agency from a slew of crippling legislation that I am convinced the Congress might have enacted in the heat of hysteria.” And then there was also this: “As a matter of conscience, I was obliged to cooperate if I were to abide by my oath to support and defend the Constitution.”17

Hal Bean, a senior CIA officer, later recalled those difficult times and how Colby had handled them: “Even during the height of the excessive abuse he was subjected to by staff and members of Congress, he maintained a dignity and calm that few of us could have matched under the circumstances—and he did so with little or no support from those for whom he worked.”

In 1989 Colby published a second book, this one entitled Lost Victory: A Firsthand Account of America’s Sixteen-Year Involvement in Vietnam. In it he described how mistakes in the White House and the Pentagon, including support for the overthrow of South Vietnam’s President Ngo Dinh Diem, the decision to introduce massive U.S. ground forces into the war, and failure to develop a political strategy for rural Vietnam brought chaos to Vietnam and forfeited the support of the American people.

“Even today,” he noted in retrospect, “most Americans believe the cause was hopeless. In fact…South Vietnam defeated the communist guerrillas and threw back a massive North Vietnamese military assault in 1972, after a half million U.S. troops had already been withdrawn.”

Colby’s book of course incensed anti-war elements whose contention was that nothing good was or could have been done in Vietnam, but it in fact constituted a balanced, reasonable, restrained account of the opportunities, accomplishments, and missed chances of a complicated war. In this it was very like the man himself, modest, insightful, and devoted to duty. Wrote journalist Zalin Grant, who had known Colby: “I considered him the most capable and effective American to serve in the Vietnam War.”18

In Vietnam Ambassador William Colby, Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker, and General Creighton Abrams fought as hard as they could for as long as they could with everything that was left to them to try to help South Vietnam win the war. Maybe others in Washington or elsewhere were interested in stalemate or disengagement or some other palliative solution, but these three men and the forces they led were striving for just one thing—victory, defined as a South Vietnam capable of defending itself and determining its own political, economic, and cultural future. In so doing, they by their actions defined stewardship—doing the best you can with what you have to work with, and doing it with selflessness, dignity, and integrity.

Colby met an untimely death under suspicious circumstances, found dead in April 1996. While the official investigation was inconclusive, a further inquiry by Zalin Grant stated very simply: “This was a murder, not an accident.”19

Colby was bade farewell in grand and moving funeral rites at Washington National Cathedral, then laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery. Eulogizing him in a later essay, senior CIA veteran Hal Ford wrote this: “All in all, Bill Colby was a person of integrity, not afraid to tackle tough problems others would duck, and certain that intelligence will remain an honorable and needed profession. Above all, he is to be remembered for his conviction that we Agency people are American citizens first and must be responsive to Constitutional demands more than to any self-created CIA code of separateness. We are all fortunate to have known this honorable colleague. He will be missed, but his integrity and broad vision will remain models for the rest of us intelligence officers and our successors.”20

Vietnam veteran and military historian Colonel Harry Summers added this succinct observation: “Colby won his war. Too bad his leaders did not have his backbone and strength of character to win their war as well.”21

- Under Colby the acronym was soon changed to stand for Civil Operations and Rural Development Support.

- Lewis Sorley, A Better War (NY: Harcourt Brace, 1999), p. 70.

- Ibid., Rosson interview.

- William E. Colby Deposition, in Vietnam: A Documentary Collection: Westmoreland vs. CBS (NY: Clearwater Publishing, 1985), p. 100. Microform.

- Amb. Ellsworth Bunker, Oral History (unpublished transcript).

- Tom McCoy, as quoted in Thomas Powers, The Man Who Kept the Secrets: Richard Helms and the CIA (NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1969), p. 182.

- Lewis Sorley, ed., Vietnam Chronicles: The Abrams Tapes, 1968-1972, p. 55.

- Ibid., p. 16.

- Sorley, Vietnam Chronicles, p. 51.

- Territorial Forces (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1978), pp. 34, 127.

- Ibid., pp. 122-123.

- William E. Colby, Oral History Interview. LBJ Library

- U.S. Congress, Senate, Committee on Foreign Relations, Vietnam: December 1969, A Staff Report, p. 4. Preliminary results for the following year, through October, indicated “the percentage killed was almost double that in 1968.” Ibid. Through 31 July 1972, Mark Moyar established, a total of 81,740 VCI had been neutralized (26,369 killed, 33,358 captured, and 22,013 rallied). See Phoenix and the Birds of Prey, p. 236. Meanwhile the enemy, who were running a real assassination program aimed at innocent civilians, executed an estimated 36,725 through 1972. See Harry Summers, Vietnam War Almanac, p. 284.

- Directive No. 01/CT 71, as quoted in Gareth Porter, ed., Vietnam: The Definitive Documentation of Human Decisions, 2 vol. (Stanfordville, NY: Coleman Enterprises, 1979), p. II:551.

- Olivier Todd, Cruel April: The Fall of Saigon (NY: W. W. Norton, 1990), p. 79.

- William Colby, Honorable Men: My Life in the CIA (NY: Simon and Schuster, 1978), p. 16.

- Ibid., pp. 19, 20.

- Zalin Grant’s War Tales

- Ibid., p. 7.

- Hal Ford, “Bill Colby Remembered: A Personal Recollection,” CIRA Newsletter (Summer 1996), p. 20.

- Harry Summers, “William Colby: He Won His War,” Army Times (13 May 1996), p. 54.

About the Author:

Lewis Sorley, a Vietnam veteran, is the author of A Better War: The Unexamined Victories and Final Tragedy of America’s Last Years in Vietnam and biographies of Generals Creighton Abrams, Harold K. Johnson, and William Westmoreland.

Leave A Comment