Air Operations for the Son Tay Raid

By Colonel John Gargus (USAF, Retired)

Originally published in the November 2016 Sentinel

Planners of the bold attempt to rescue American prisoners of war from North Vietnam on November 21, 1970 put together a small joint special operations force that was believed to be just right for the task. They never anticipated that their carefully orchestrated operation would balloon into what became the largest nighttime operation of the Vietnam War up to that date. Even though today’s military historians laud the raid on the Son Tay prison camp as a model for a successfully executed joint special operations mission, they do not address the extremely large air support it generated. Instead they focus their attention on the meticulous small force training of this joint service force in Florida and on its great professional performance during the raid itself.

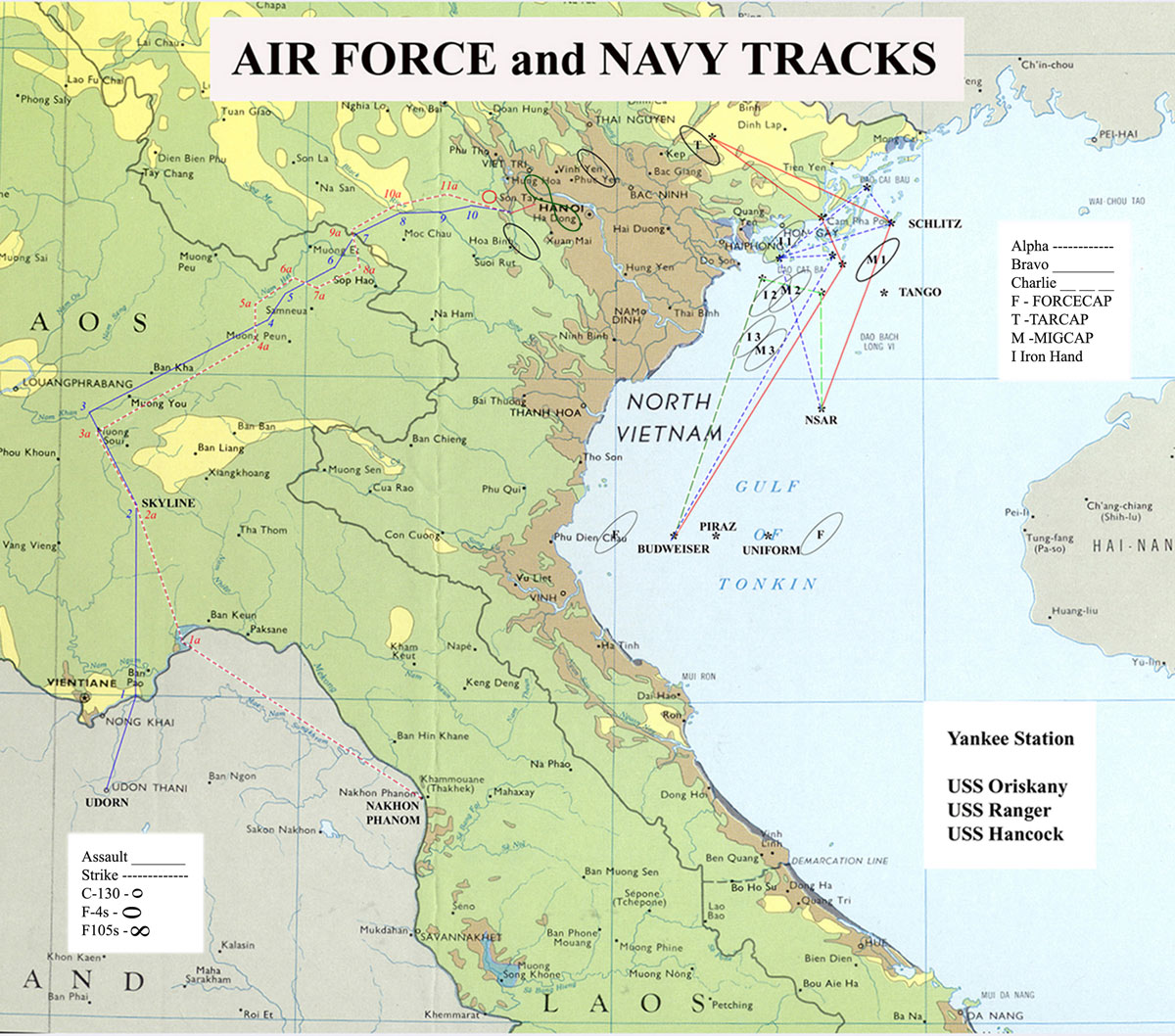

The well-conceived Operation Ivory Coast plan called for a small joint force of Army and Air Force Special Forces to train in Florida. This had to be done away from Vietnam to ensure top secret security for the project. Once ready, the force was secretly inserted into the war zone for execution with minimal support from the US forces conducting the war. The Green Berets did not require any Army support because they brought everything they needed with them. They were secretly flown into a well-guarded isolation facility at the staging base at Takhli in Thailand. Air Force requirements were more involved because in theater air assets had to be borrowed to execute the raid under a new name called Operation Kingpin. Only two Combat Talon C-130s and two College Eye EC-121s flew in from the States. Helicopters and fighter aircraft had to be provided by theater units, hopefully with minimal impact on their war operations. After all, the raid was planned to be just a one night event. The Navy did not participate in the stateside planning and training, however, the planners wanted to have the carriers in the Gulf of Tonkin launch few aircraft to provide a diversion for the raiding aircraft which would enter into North Vietnam from Laos.

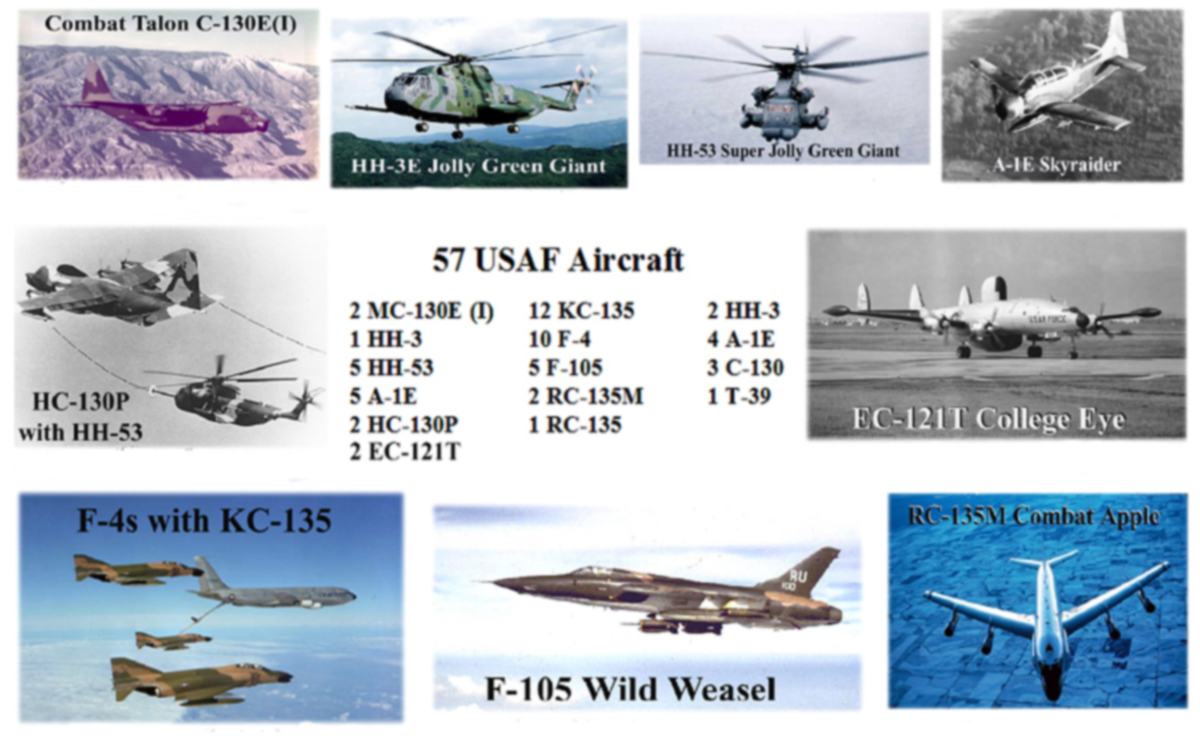

The most directly involved aircraft numbered only 15. There were two very special Combat Talon MC-130s with highly classified navigation and electronic systems that allowed them to operate inside of the heavily defended North Vietnamese air space. One Talon would escort the Assault Formation which had 56 Army rescuers in five Jolly Green Giant HH-53 helicopters and one HH-3 helicopter. The other would escort the Strike Formation with five A-1E fighters that would provide low level protection for the ground troops in the objective area. The planners always wanted to have a couple of high flying jets to protect the low flying formations against the North Vietnamese MIG interceptors. These high flyers would not only discourage the enemy against launching the MIGs, but would also invite a high altitude surface to air missile (SAM) response that would not impair the ground and low flying activity in the objective area. The two stateside College Eye EC-121T radar platforms were needed to monitor the Son Tay area from the Gulf of Tonkin and provide the high flying jet fighters vectoring against any enemy interceptors that would take off to challenge the aircraft fleet.

Theater coordination for the raid did not take place until November 1 when the top three planners departed for Southeast Asia to brief the top officials who commanded our country’s military services. They were: Army Brig. Gen. Donald D. Blackburn, Special Assistant for Counterinsurgency and Special Activities (SACSA), under whose domain the raid plans generated; and Air Force Brig. Gen. Leroy J. Manor, Commander of the Air Force Special Operations Forces (AFSOF), who became the chief of the raiding Joint Contingency Task Group with his deputy the legendary Army Col. Arthur D. Simons. The reception from the limited number of key officials whom they briefed in on the daring plan was overwhelming. All offered unlimited support for the rescue plan. Army General Creighton Abrams, who directed the overall war effort from Saigon, was disappointed that the Army raiders did not need any of his troop support other than allowing the ready to execute force into his area of responsibility and ensuring utmost security for this important operation. The Seventh Air Force promised the trio unquestioned support and made sure that all Air Force units gave the raid coordinators everything they asked for without asking any questions. That opened the floodgate of enthusiastic support for the raid from the selected few who were tasked to support it.

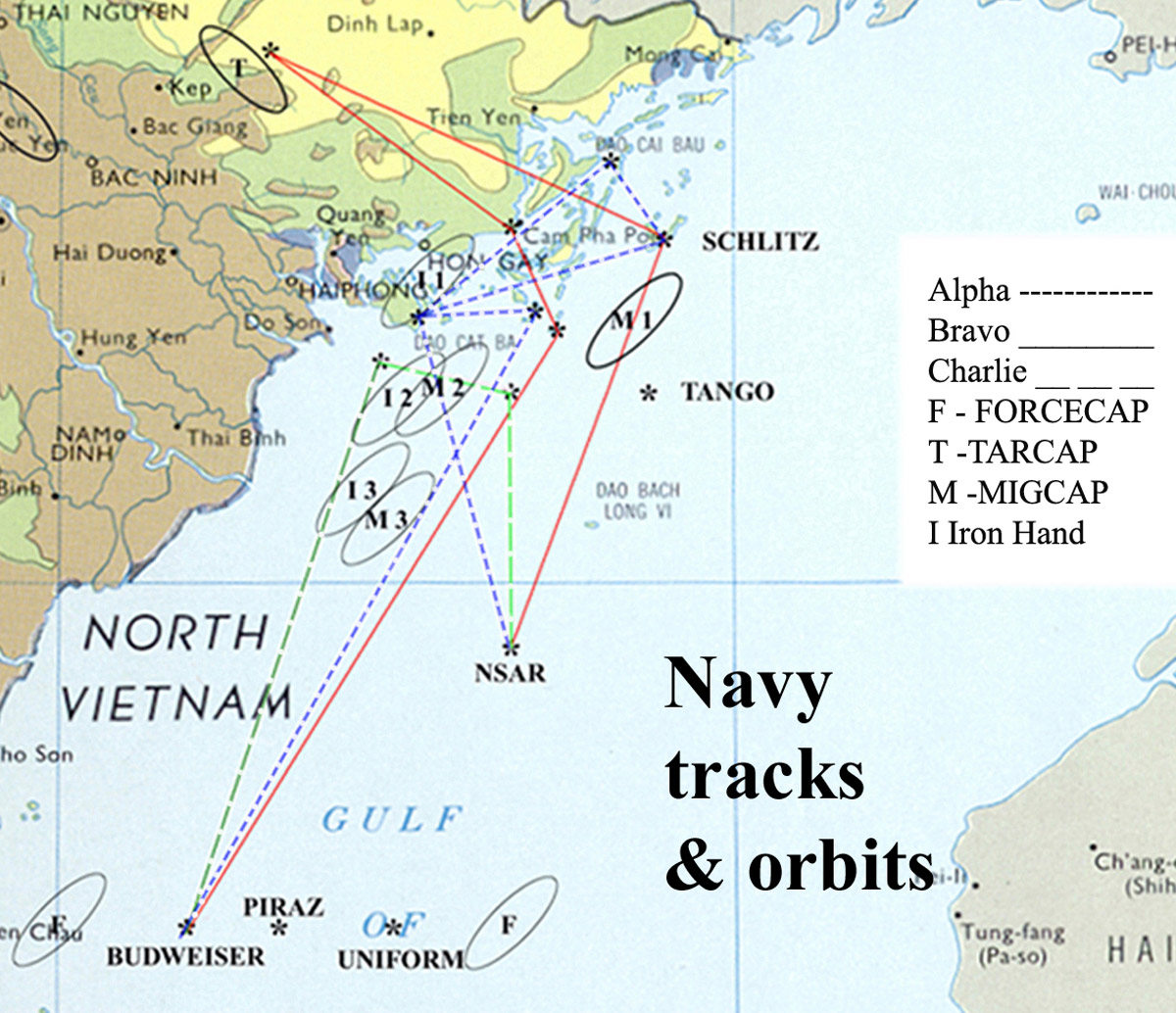

On the way home, Gen. Manor and Col. Simons stopped at the Yankee Station in the Gulf of Tonkin. There, Admiral Frederick A. Bardshar, Commander of Task Force 77, promised them very encouraging support to stage a credible show of force from the Yankee Station to distract the enemy from focusing on the incursion of the raider force into the Son Tay area from the west. He welcomed the idea of sending his pilots north of the 20th parallel because there was an ongoing self-imposed bombing pause for targets in Hanoi and Haiphong areas since 31 March 1968. He knew that his pilots would love to hit those lucrative targets before rotating back to their home ports. However, the raiders had very strict rules of engagement. The only ordnance the Navy was authorized to dispense were Mark 24 flares to make the North Vietnamese wonder what kind of an attack was being staged. They were not allowed to attack any ground targets. However, their pilots could defend themselves against enemy interceptors and SAMs if they challenged them.

BG Donald D. Blackburn

BG Leroy J. Manor

COL Arthur D. Simons

By November 17, just three days from the night of the raid, the planners were ready to task the needed Air Force units for their support. As one of the briefers and a member of the air operations planning staff, I was astonished at what ensued with the invited planners of each Air Force unit we included on our operation. Their enthusiasm for what we were about to do was incredible. All were eager to fly into the restricted target zone north of the 20th parallel. They assured us that their fighter pilots would be eager to fly into this forbidden zone even with the strict engagement restrictions for our small scale surgical operation. They were not allowed to attack opportune targets outside of the small Son Tay geographical area. What was even more incredible for me was when these planners from Udorn, Korat and U-Tapao bases returned on the following day with their concept for our raid support. In Florida we started with such a small number of aircraft and now we were advancing past that special operations requirement for minimal, but optimum force. I worked with each planner on incorporating their flight tracks into our fixed and carefully orchestrated timing and inbound routes for the raid. This timing was designed to take advantage of the 0200 shift change for the prison guards.

Only the two HC-130P takers for helicopter refueling on the way in and out remained as we planned for in Florida. The number of couple of F-4 fighters we wanted for high altitude bait for SAMs and for ensuring that the enemy’s interceptors did not get launched against us increased to ten. There would be two packages of five F-4 MIG killers that would launch in two waves, ensuring that there would be four of them high overhead throughout the ground operation, with one off to the side as a replacement spare if someone got shot down. Next, because we anticipated a SAM defense from the enemy, we needed F-105s to fly a missile suppressing mission. That package came to five more aircraft to cover the 30 minute time period we planned to be on the ground. Naturally, these fifteen newly added aircraft required refueling support. Shockingly, this added another twelve KC-135 tankers. These would be deployed, not only over Laos to support the jets from Thailand, but also over the Gulf of Tonkin to refuel three Air Force C-135s and any Navy aircraft needing emergency fuel. Normally, there was one RC-135M, Combat Apple from Okinawa flying over the Gulf monitoring all electronic transmissions from North Vietnam. It had Vietnamese speakers on board who translated voice transmissions and issued MIG warnings to friendly aircraft. This RC-130M maintained continuous contact with the command post at Monkey Mountain near Da Nang. Brig. Gen. Manor was going to be commanding the raiding force from there. His command post back up, Col. Norman Frisbie was going to be on board of Combat Apple One. We needed a spare Combat Apple. So on the night of the raid, there would be two RC-135Ms flying over the gulf. In addition, we decided to have all the electronic traffic generated by the raid recorded and for that we needed a specially configured RC-135 from U-Tapao, Thailand. Finally, we must add to this growing number three regular C-130s that were used to shuttle the planners and troops between the Thai bases as well as the T-39 for Brig. Gen. Manor’s staff. This brought up our originally planned 15 aircraft to 57.

One thing we did not plan on was the approaching Typhoon Patsy. Because of that nature’s event Brig. Gen. had to move the raid up by 24 hours. It was either that or postpone it for several days. Such postponement would carry with it potential for a mission compromise. Preparations for an unprecedented nighttime operation from five Thai bases was sure to generate some suspicions among the servicing flight line crews. There would be too many available days for speculations if the mission did not go early. This was one of the reasons we did not get to review the Navy plan for the raid which did not became available to us until we were in our pre-departure crew rest. I learned of it after we landed at Udorn empty handed. Incredibly, the Navy surpassed the Air Force in the number of aircraft they launched. They employed 59 aircraft, two more than the Air Force, to provide a very convincing diversion to our attack on Son Tay.

The Navy had three carriers at the Yankee Station in the Gulf of Tonkin: The USS Ranger, the USS Oriskany and the USS Hancock. They launched twenty-two A-7 attack aircraft on three tracks dropping only flares. These fighters required six dedicated carrier based A-7 takers and seven land based tankers from Da Nang. One of them was KA-3B and six were EKA-3Bs that also provided electromagnetic jamming of enemy radars. They flew two E-1B radar platforms to direct four F-4 MIG killers. Five A-7s flew Iron Hand SAM suppression missions. Eight fighters (six F-8s and two F-4s) flew protective orbits for the Yankee Station and for all other airborne aircraft. Finally, there were four A-7s dedicated to rescue and one EP-3 from Guam, which had the same mission as the Air Force’s Combat Apple from Okinawa. Consequently, not counting the always ready rescue helicopters, the Navy launched 59 aircraft to support the Son Tay raid.

Counting the five Air Force aircraft flying over the Gulf of Tonkin that night, the North Vietnamese radars had 63 distracting targets to look at in the east while the Florida trained Attack and Strike Formations with only 13 aircraft sneaked into Son Tay undetected. None of the planners who started working with these 13 aircraft anticipated the employment of 116 to support the 56 men we put down on the ground. Likewise, none of us anticipated to return home empty handed.

About the Author:

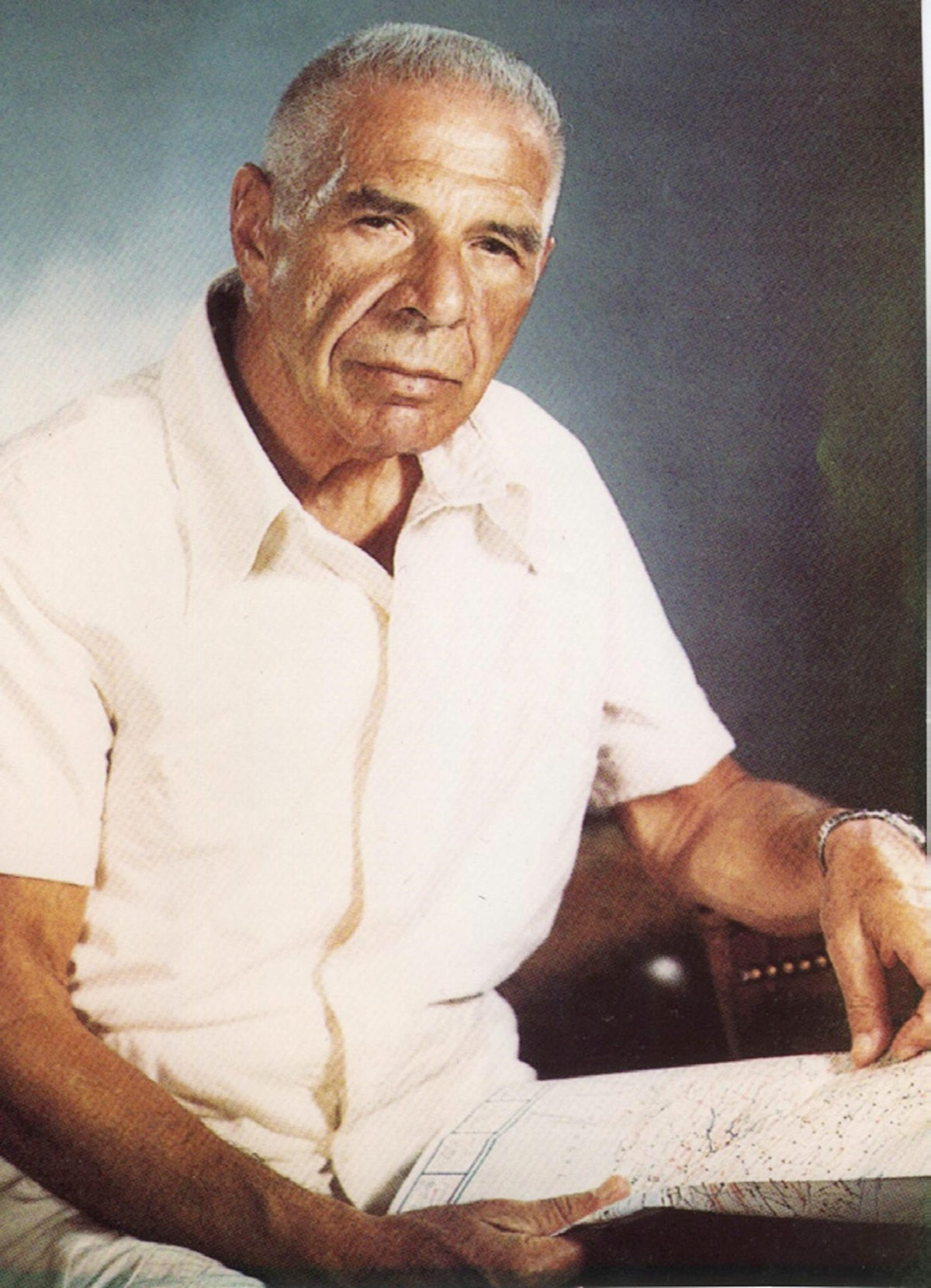

John Gargus was born in Czechoslovakia, from which he escaped at the age of fifteen when the Communists pulled the country behind the Iron Curtain. He was commissioned through AFROTC in 1956 and made the USAF his career. He served in the Military Airlift Command as a navigator, then as an instructor in AFROTC. He went to Vietnam as a member of Special Operations and served in that field of operations for seven years in various units at home and in Europe. He participated in the air operations planning for the Son Tay POW rescue and then flew as the lead navigator of one of the MC-130s that led the raiders to Son Tay. His non-flying assignments included Deputy Base Command at Zaragoza Air Base in Spain and at Hurlburt Field in Florida, and a tour as Assistant Commandant of the Defense Language Institute in Monterey, California. He retired in 1983 after serving as the Chief of USAF’s Mission to Colombia. He has been married to Anita since 1958. The Garguses have one son and three daughters.

JohnGargus

Flight hours: More than 6100 hours (381 Combat flying hours in Southeast Asia and 105 flying hours with the Colombian Air Force).

A partial list of Colonel Gargus awards and decorations:

- Silver Star

- Distinguished Flying Cross w/OLC

- Bronze Star

- Defense Meritorious Service Medal

- AF Meritorious Service Medal

- Air Medal w/5 OLC

- AF Commendation Medal

- Presidential Unit Citation w/OLC

- Navy Presidential Unit Citation

- AF Outstanding Unit Award w/2OLC

- Combat Readiness Medal w/OLC

- National Defense Service Medal

- Vietnam Service Medal w/4 Service Stars

Foreign Awards

- Spanish Aeronautical Merit Cross with White Badge

- Republic of Vietnam Air Service Medal

- Republic of Vietnam Air Force Navigator Wings

- Colombian Air Force Aeronautical Merit Cross

- Colombian Air Force Navigator Wings

Leave A Comment