A JOURNALIST’S FIRST TRIP TO A COMMUNIST COUNTRY

Laos — My cyclo driver outside the Lane Xang Hotel, Vientiane (Photo courtesy Marc Yablonka)

By Marc Yablonka

This article first appeared in the Hmong Daily News on December 26, 2022.

The night before I flew out of Bangkok for Vientiane, Laos in 1990, I confessed to the director of the UNHCR office at the Hmong section of the Panat Nikhom refugee camp that I was nervous because it would be the first time I’d ever been in a communist country. I had certainly interviewed enough Lao and Hmong refugees, and recorded their horrific stories for my master’s thesis at USC on their plight, to “earn” that nervousness. She just laughed.

And the next morning when I deplaned at Wattay International Airport, spied the big blue-painted barn that then passed for an airport terminal, and spotted several uniformed Communist Pathet Lao soldiers with their typical wide brimmed, red banded, Soviet style dress hats, I didn’t feel any less apprehensive.

I deplaned with a young French-Cambodian woman, Phaly Pao, from Lyon, France. Phaly and her family had escaped Cambodia by boat in the late 1970s during the reign of the despot Pol Pot and his murderous Khmer Rouge. This was to be her first trip home to Phnom Penh. A trip she was going to have to make from Vientiane in a rickety old Russian helicopter since airplane flights between the two Indochinese capitals had yet to be established in 1990.

Phaly and I had befriended one another at the gate of our Thai Air flight at Don Muang International Airport during a delay. Between her very broken English and my high school French, I was able to understand that she was not sure where she would stay in Vientiane.

“Je loge à l’hôtel Lane Xang,” I told her in French. “Why don’t you try there?”

At Wattay, as we walked through the plane’s open door together, we viewed those Pathet Lao soldiers. Phaly appeared a frightened child. She looked up at me and said, “I think I stay at Lane Xang Hotel…with you!”

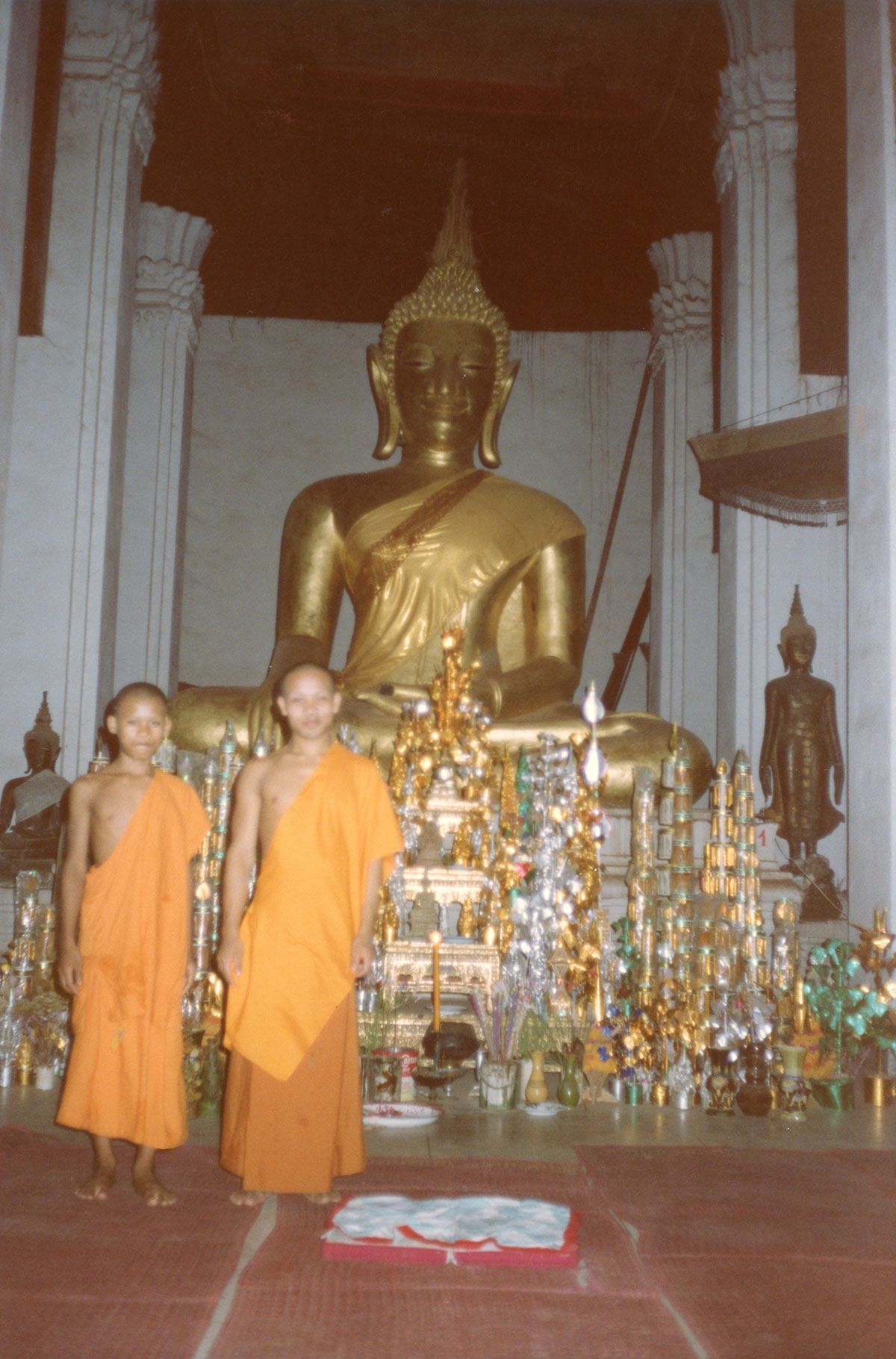

Buddhist monks in Vientiane. (Photo courtesy Marc Yablonka)

The Patuxet Monument, Vientiane. (Photo courtesy Marc Yablonka)

Thirty-two years is a long time, and all I remember is breakfasting with my new friend, touring the Buddhist temples of Vientiane with her, and the desk clerk at the hotel handing me a farewell note from Phaly, whose helicopter I could not see off because I’d arranged to interview the Bishop of Vientiane, Apostolic Vicar Jean Khamse Vithavong, for the National Catholic Register newspaper.

As my cyclo driver pedaled me through the city enroute to its main Catholic church, as I wrote in my book about my time in Laos, Tears Across the Mekong, in 2015, “Throughout the city, loud speakers mounted strategically on decrepit telephone poles, looking like they’d emerged from the French era (which, like the telephones they connected, they indeed had) blared the latest edition of Marxism/Leninism Lao style while thousands of electrical wires meshed overhead in total chaos.”

When my cyclo driver deposited me at the Church of the Sacred Heart, I was confronted by a structure badly in need of a new coat of paint. Its leaning steeple reminded me of Italy’s Leaning Tower of Pisa.

Inside, however, a warm Bishop Vithavong, clad in a blue jumpsuit, greeted me and welcomed my questions about the state of the Catholic Church in Laos. He confessed to me that since 1975, when Laos, like neighboring Vietnam, fell to communism, there had been a “brain drain” in the Church because so many priests and nuns had fled the country in fear for their lives.

I was to meet one of those priests, Father Lucien Bouchard, whom I interviewed for Tears Across the Mekong, 25 years later. But for the most part, the bishop told me, everything was “Bo Pinh Yan.” A typical Lao expression meaning “Everything is okay.” He did, however, admit that the government placed certain restrictions on worship.

Church Of The Sacred Heart, Vientiane (Photo courtesy Marc Yablonka)

Later, while at the Souriya restaurant across the dusty road from the Lane Xang, I spotted Anne Mills Griffith, director of the National League of POW/MIA Families, strategizing with US Embassy types over her search for prisoners of war and our missing in action. I thought of how many broken hearts she must have encountered Stateside and silently wished her well.

One afternoon, I strode into the bar of the Lane Xang, where a group of people were intently listening to the news on CNN, which the Lao government then allowed for two hours a day. I heard the unmistakable sound of cannon fire. My eyes settled on the sole Caucasian gentleman in the bar. Mistaking him for French, I asked, “Qu’est qui se passe?” (“What’s happening?”). In a thick Russian accent, he replied in English, “America attack Iraq.”

Just then, another unmistakable sound occurred. That of a Russian MiG jet soaring loudly overhead. That was not the only time I was to hear a MiG take off from Wattay.

The next day as I again walked into the bar, decked out in the typical journalist attire: shirt with epaulets, cargo pants about an inch too short, and chukka boots, vowing not to blunder in French anymore, I heard a voice from across the room shout at me, “You waiting for a flood?”

That was my introduction to Don Scott, a man so dedicated to the resettlement of Indochinese refugees that it eventually took his life at the young age of 62. Don rattled a lot of cages in Washington, D.C. because he strongly felt that we owed the American brand of freedom and peace to the people from Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia that we had left behind. That we promised to help and then broke that promise in 1975 when we departed Indochina.

But Laos in the 90s was not Don’s first taste of Southeast Asia. He and his wife Marilyn, both UCLA graduates and pacifists, had headed up the San Diego-based Christian group Project Concern’s hospital in Lien Hiep in Vietnam’s Central Highlands during the war. A hospital that often had a Viet Cong cadre in a bed right next to an American soldier’s bed.

At one point, the hospital was overrun by Viet Cong. When that happened, Don rushed out in the middle of the melee, grabbed the AK-47 off one of the VC and tossed it into the jungle. The VC was so frightened that he ran away. The same year I befriended Don, his time in Vietnam was chronicled in a CBS Sunday Night Movie of the Week, “Vestige of Honor: The Don Scott Story.”

Just before I left Vientiane, I had gotten permission through my government minder to visit the wondrous old royal capital of Laos, Luang Prabang, Sadly, it was also the site where most of the Royal Lao family had been systematically murdered by the Pathet Lao.

The night before my flight though, over a dinner of larb, the national dish of Laos, my minder took me aside and whispered, “Mr. Marc, Lao aviation sometime crash.” Mr. Marc quickly changed his mind, flew Thai Air back to Bangkok, where he made plans to report from the second communist city he would soon touch down in: Saigon.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR — Marc Yablonka is a military journalist whose reportage has appeared in the U.S. Military’s Stars and Stripes, Army Times, Air Force Times, American Veteran, Vietnam magazine, Airways, Military Heritage, Soldier of Fortune and many other publications.

Between 2001 and 2008, Marc served as a Public Affairs Officer, CWO-2, with the 40th Infantry Division Support Brigade and Installation Support Group, California State Military Reserve, Joint Forces Training Base, Los Alamitos, California. During that time, he wrote articles and took photographs in support of Soldiers who were mobilizing for and demobilizing from Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom.

His work was published in Soldiers, official magazine of the United States Army, Grizzly, magazine of the California National Guard, the Blade, magazine of the 63rd Regional Readiness Command-U.S. Army Reserves, Hawaii Army Weekly, and Army Magazine, magazine of the Association of the U.S. Army.

Marc’s decorations include the California National Guard Medal of Merit, California National Guard Service Ribbon, and California National Guard Commendation Medal w/Oak Leaf. He also served two tours of duty with the Sar El Unit of the Israeli Defense Forces and holds the Master’s of Professional Writing degree earned from the University of Southern California.

The movie “Vestige of Honor” has been posted to SFA Chapter 78’s YouTube channel in the More SF History playlist. You can view it at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dzm6QJahDkc

Thank you for posting it Debra!