A Combat First:

Army SF Soldiers in Korea, 1953-1955

Part 1

By Kenneth Finlayson

From the ARSOF publication, Veritas, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2013

https://arsof-history.org/articles/v9n1_sf_in_korea_page_1.html

The Korean War is noteworthy in Army history for the first use of Army Special Forces (SF) soldiers in a combat theater. In 1953, ninety-nine graduates from the first two Special Forces Qualification Course classes deployed to Korea as individual replacements. Working alongside their conventional Army counterparts, they performed a variety of missions associated with the training and employment of guerrilla forces. Two, Second Lieutenant (2LT) Ivan M. Castro and Captain (CPT) Douglas W. Payne, paid the ultimate price for their service and were the first SF soldiers to die in combat. Some of the SF men remained in Korea until 1955, nearly two years after the signing of the Armistice. This article documents the experience of the SF soldiers who trained, advised, and ultimately demobilized the guerrillas.1

The Korean War (1950-1953) ended in a negotiated ceasefire with the armies of North Korea and Communist China opposing the forces of South Korea, the United States and the United Nations coalition along the 38th Parallel. The first year of fast-paced, fluid, ground combat up and down the Korean peninsula was followed by a gradual stalemate as the armies of both sides hardened their defensive positions and jockeyed for control of key terrain along the Main Line of Resistance (MLR).2 While the conventional war ground to a halt, unconventional warfare (UW) operations continued on both coasts.

Far East Command (FEC) began to develop an UW capability in early 1951 by taking advantage of the large numbers of anti-Communist North Korean guerrillas on the northwest islands of Korea. This led to the formation of the Attrition Section, Miscellaneous Division, G-3, Eighth U.S. Army (EUSA) on 15 January 1951.3 The guerrilla unit went through a dizzying series of name changes and command relationships; from the Attrition Section, EUSA G-3, to the Miscellaneous Group, 8086th Army Unit (AU), EUSA on 5 May 1951; then to the Guerrilla Section under the FEC/Liaison Group (FEC/LG) (in Tokyo) and the FEC/Liaison Detachment, Korea (FEC/LD[K]) (in Taegu). On 10 December 1951 the section was renamed the 8240th Army Unit, FEC G-2. Ultimately it came under the operational control of the Combined Command for Reconnaissance Activities, Korea (CCRAK), 8242nd AU on 27 September 1952.4 Throughout these many permutations, the focus remained on the guerrillas.

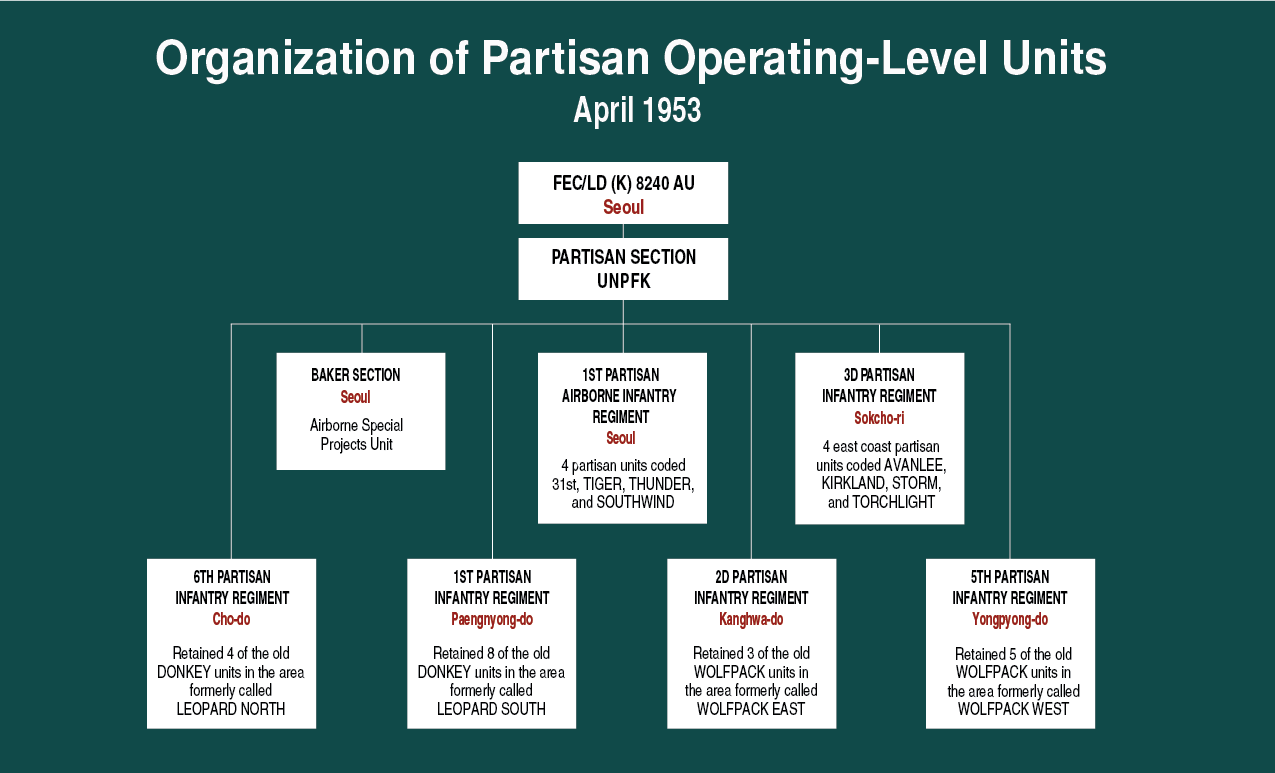

In 1953 the LEOPARD and WOLFPACK units were reorganized into Partisan Infantry Regiments. American advisors worked with the guerrilla chain-of-command at the regiment down to the guerrilla companies. (U.S. Army)

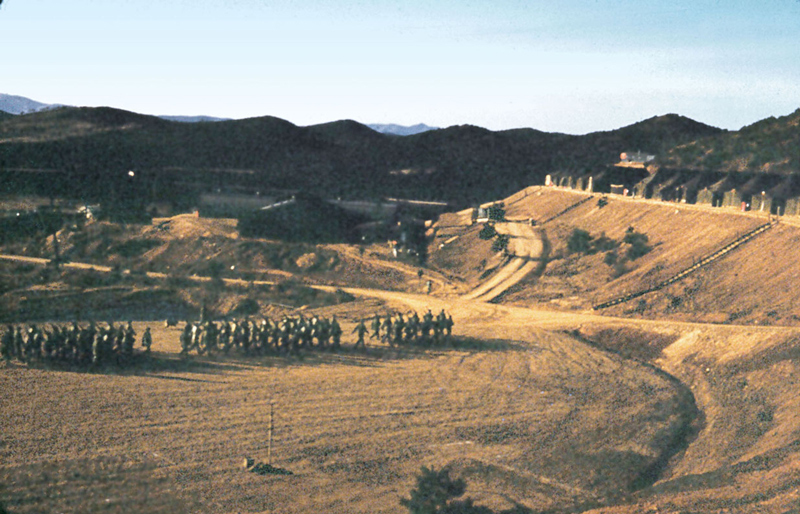

A guerrilla formation. Both LEOPARD BASE and WOLFPACK organizations were supplied and equipped by the U.S. The level of support depended on the unit strength, a number that often varied widely from one day to the next. (U.S. Army)

On 15 January 1953, another unit was formed, the Recovery Command, 8007th AU. The 8007th also used guerrillas to collect information related to UN prisoners of war and gather general combat intelligence. Like the guerrilla command, the Recovery Command fell under the staff supervision of the FEC G-2. In September, 1953 it became the 8112th Army Unit.5 Most of these changes reflected attempts to create a theater-level command to direct UW operations, but had little effect on the basic mission of the guerrillas and the American advisors who trained, supplied and employed them. As the war progressed, the requirements for support grew.

The mission of the guerrilla command, as defined in the Table of Distribution was twofold. The first was: “to develop and direct partisan warfare by training in sabotage indigenous groups and individuals both within Allied lines and behind enemy lines,” and second; “to supply partisan groups and agents operating behind enemy lines by means of water and air transportation.”6 To accomplish these missions, in early 1952 the guerrilla command divided into two elements for operations and support.

Ultimately, three sub-commands controlled guerrilla operations; initially LEOPARD BASE and later WOLFPACK on the West Coast, and Task Force (TF) KIRKLAND on the East Coast. The support element, BAKER Section, was initially located at the EUSA Ranger Training School at Kijang near Pusan, and used C-46s and C-47s to support airborne training and to conduct aerial resupply and agent insertions. BAKER Section later moved to K-16 Airfield outside Seoul, after the capital was retaken a second time.7

On the west coast, LEOPARD BASE, originally called WILLIAM ABLE BASE, was located on Paengny?ng-do.8 Formed in February 1951, it supported roughly twelve thousand men organized into fifteen units referred to as numbered Donkeys. The LEOPARD area of operations was generally above the 38th Parallel to the west of the Ongjin Peninsula, reaching as far north as Taehwa-do near the mouth of the Yalu River that formed the Chinese- North Korean border.9 Eight Donkeys were located on Cho-do and the remaining seven on other islands. An advisor to Donkey 1, Sergeant (SGT) Alex R. Lizardo’s experience was typical.

Enlisting in July 1951, Alex Lizardo attended Infantry Basic Training at Fort Ord, California and Airborne School at Fort Benning, Georgia. Promoted to Sergeant (SGT) within eleven months of enlisting, he was sent to the FEC/LD (K). Arriving in June 1952, SGT Lizardo remained there for the next six months. After returning to Camp Drake, Japan for additional training, he was assigned to LEOPARD in November 1952 to be an advisor to Donkey 1.10

“Donkey 1 was out on Kirin-do. We Americans did not usually accompany the raiding parties on-shore,” recounted SGT Lizardo. “I was not a school-trained Special Forces guy, but I was later awarded the SF Tab [and Combat Infantryman’s Badge] for my time in 8240.”11 His assignment to LEOPARD coincided with the height of guerrilla activity. LEOPARD had been operational a year when the third guerrilla element, WOLFPACK, was organized (January 1952).

Origins of the term ‘Donkeys’

The origins of the term ‘Donkey’ for identifying West Coast guerrilla units are unclear, but its use began early at WILLIAM ABLE Base. One probable origination is related to COL McGee’s first speech to the guerrilla leaders on Paengnyong-do. In that meeting he advised them to not be rash, but instead “behave like the mule which [when entangled in wire] stubbornly, patiently awaits the arrival of outside help.” His interpreter substituted the more familiar ‘donkey’ for mule, and the name apparently stuck. Another possible origin was put forward by an early Donkey leader who stated “the generator of the [AN/GRC-9] radio looked like a Korean donkey or ass. When you crank the generator…you have to ride on the generator which looks like a rider on the back of a donkey.” Regardless of how the term originated, individual guerrilla units began referring to themselves after McGee’s visit as ‘Donkeys.’ Units became identified as a numbered ‘Donkey’ (example: ‘Donkey 6’).

“Darragh Letter,” 13; “UN Partisan Forces,” 93-94; see also Kenneth Finlayson, “Wolfpacks and Donkeys: Special Forces Soldiers in the Korean War,” Veritas 3, No. 3 (2007), 32-40.

WOLFPACK, composed of eight sub-units designated WOLFPACK 1 thru 8, totaled 3,800 partisans.12 The headquarters was on the large island of Kangwha-do west of Seoul. WOLFPACK 1 performed base security on Kangwha-do. The other units were located on adjacent islands south of the 38th Parallel.

“Our mission was to harass and interdict the rear areas. We conducted raids and ambushes and laid mines along the MSRs [Main Supply Routes].” — MAJ Richard M. Ripley

WOLFPACK conducted operations behind enemy lines in the southern portion of the Ongjin Peninsula.13 Armor Major (MAJ) Richard M. Ripley commanded WOLFPACK in the spring of 1952. “Our mission was to harass and interdict the rear areas. We conducted raids and ambushes and laid mines along the MSRs [Main Supply Routes].”14 As the war stalemated, LEOPARD and WOLFPACK grew with the arrival of more anti-Communist North Korean refugees.

By late 1952, the guerrilla units on the West Coast were actively raiding the North Korean mainland to harass the enemy and disrupt traffic along the MSRs.15 LEOPARD reported a strength of 7,002 guerrillas and WOLFPACK, 7,015.16 A compilation of the two unit operational reports for the week of 15-21 November 1952 reflected 63 raids and 25 patrols against the North Korean coast, claiming an estimated 1,382 enemy casualties.17 The increasingly robust partisan forces (and their many dependents), were difficult to control, supply, and feed. The situation dictated a reorganization in order to streamline operations.

In 1953, Guerrilla Command labeled their sub-elements the United Nations Partisan Forces in Korea (UNPFK), but retained the headquarters names LEOPARD and WOLFPACK.18 The separate Donkeys and Wolfpack sub-elements were reorganized into five infantry regiments and one airborne infantry regiment. The non-airborne units were called the Partisan Infantry Regiments (PIR) 1st, 2nd, 5th and 6th. TF KIRKLAND, conducting operations on the East Coast, became the 3rd PIR. The airborne regiment became the 1st Partisan Airborne Infantry Regiment (PAIR). The regiments retained their original North Korean leaders and referred to themselves as Wolfpacks and Donkeys. American advisors worked at the regimental level and below or served as UNPFK staff. It was during this period of reorganization that the request for Special Forces soldiers to serve in Korea was initiated by Brigadier General (BG) Robert A. McClure.

From the beginning of the war, McClure, the Army Chief of the Office of Psychological Warfare (OCPW), closely followed the UW activities in Korea. He was dissatisfied with the guerrilla operations, calling them “minor in consequence and sporadic in nature.”19 The Psywar general was actively working to develop a special operations capability in the Army.

The Headquarters of the 8240th AU in Seoul. The administration and logistical support to the American advisors emanated from this unit of the guerrilla command. (U.S. Army)

The anti-Communist guerrillas occupying the islands off the coast of Korea provided a valuable source of manpower to the UN forces. American Special Forces advisors helped to train the guerrillas in the late stages of the war. (U.S. Army)

Within the OCPW, McClure created a Special Operations Division, staffed with veterans of World War II UW units. On his staff was Colonel (COL) Aaron Bank (the Office of Strategic Services), COL Melvin R. Blair (Merrill’s Marauders), and COL Wendell Fertig and Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Russell W. Volckmann (Philippine guerrilla leaders). After nearly a year of staff work, on 27 March 1952 the Army approved the establishment of a Psychological Warfare Center at Fort Bragg, North Carolina.20

The Center organization included a Special Forces Department responsible for the training of the new ‘Special Forces’ soldiers. Shortly after the founding of the Center, in June 1952, COL Aaron Bank stood up the 10th Special Forces Group (SFG). As trained Special Forces troops became available, BG McClure repeatedly urged the Far East Command to request them, sending messages in November 1952 and again in January 1953.21

FEC finally asked that fifty-five officers and nine enlisted men from the 10th SFG be levied for Korea. COL Fillmore K. Mearns, head of the Special Forces Department, visited Korea in early 1953 to see the guerrilla operations first- hand.22 Soon after his visit, the first contingent of SF troops arrived in theater. Ultimately, ninety-nine Special Forces men, (seventy-seven officers and twenty-two enlisted soldiers) deployed from Fort Bragg in five groups between February and September 1953.23

“We were put in the Far East Intelligence School. The three-week course covered maritime operations, raids, ambushes, demo, and put a lot of emphasis on the Korean tides and their effect on operations.” — 1LT Charles W. Norton

After graduating from Class #2 of the Special Forces Qualification Course, newly-promoted Infantry First Lieutenant (1LT) Charles W. ‘Charley’ Norton reported to Camp Stoneman, CA, enroute to Korea. As part of the fourth cycle, 1LT Norton flew to Camp Drake, Japan by Air Force C-54 Skymaster. There the new SF arrivals received additional training before going to Korea.

WOLFPACK 1 in formation on Kangwha-do. After brief stints as staff officers, 1LTs Charles W. Norton and Joseph Johnson served as advisors with WOLFPACK 1. (U.S. Army)

“We were put in the Far East Intelligence School. The three-week course covered maritime operations, raids, ambushes, demo, and put a lot of emphasis on the Korean tides and their effect on operations,” Norton recalled.24 Not everyone in the class was Special Forces. “There were Military Intelligence guys who were going to run agents into North Korea. We had maybe thirty guys in the class.”25 1LT Rueben L. Mooradian’s impression of that preparatory training was of “two ridiculous weeks of intelligence training and a mission planning exercise to capture a North Korean general.”26 After completing the course, the Special Forces soldiers were sent to the guerrilla command headquarters in Seoul where each received orders.

1LT Norton was assigned to LTC Paul Sapieha’s 2nd PIR on Kanghwa-do. “My first job was as the S-3 [operations officer], which I held for about six weeks. [Second Lieutenant (2LT)] Joe Johnson came out with me. He was the S-4 [supply officer]. His job was to keep track of rice.”27 The 2nd PIR had three battalions; the 1st and 2nd conducting operations and the 3rd battalion providing base security and training new recruits. The guerrillas received marksmanship and demolitions training from the American advisors. After his brief stint as S-3, 1LT Norton moved across the island to advise the WOLFPACK 1 commander. By the time the Special Forces soldiers arrived, the guerrilla command had a well-developed supply system and good medical support.

During World War II, Master Sergeant (MSG/E-7) Robert W. Downey was a medic in the artillery. He was assigned to the 1st PIR in March 1952. “We received our medical supplies through the FEC supply system. We had Dr. Claman [1LT Maurice A. Claman, a surgeon] who covered all the islands on a two-to-four week circuit. Our MEDEVAC capability was good, [light fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters] out of Inch’on Airport back to the 121st Evac Hospital on the mainland.”28 MSG Downey’s duties included medical training for the guerrillas and taking care of the dependents on the island.

“I tried to conduct classes on basic first aid for those selected to act as medics,” said Downey. “More time was devoted to treating the family members present. We saw lots for colds, skin rashes, and infections. There were so many family members around and they constantly needed medical treatment.”29 For the SF advisors, keeping the guerrillas equipped, trained, and fed was their first priority.

1LT Myron J. Layton, another graduate of the second Special Forces Qualification Class, underwent training at Camp Drake, before being assigned to the 6th PIR on Yong-yu-do. “Our job was to keep the training schedule moving, going from one company to another. Raids and ambushes were the main subjects,” said Layton. In addition to training, the Americans were responsible for the resupply of the units on the widely scattered islands. “The LSTs [Landing Ship, Tank] would bring the supplies, 100-pound bags of rice, and we would hump it off the beach. There were C-rations for us,” recalled Layton.30 In addition to rice, uniforms, equipment, and ammunition were given to the guerrillas.

The equipment issued was not always first-rate. “We received uniforms for issue from the hospital. Many had bullet holes in them,” said Layton. “We’d get size twelve boots for guys with size six feet. Most of them wore tennis shoes.”31

Ninety-nine Special Forces soldiers deployed to Korea from the 10th Special Forces Group. COL Aaron Bank, commander of the 10th SFG (2nd from left) and COL Charles H. Karlstadt, Commandant of the Psywar Center and School (4th from left) observe 10th SF Group training. (U.S. Army)

1LT Myron J. Layton (L) and 1LT Murl Tullis were graduates of Special Forces Class #2. Assigned to the 6th PIR in April 1953, Layton found his primary mission was “to keep the training schedule moving” as the war wound down. (U.S. Army)

A young guerrilla with an M-1 Garand rifle. Boots were not the only equipment that was often too big for the user. (U.S. Army)

The author would like to thank the many veterans who gave generously of their time for interviews and provided the photographs incorporated into this article.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Kenneth Finlayson is the USASOC Deputy Command Historian. He earned his PhD from the University of Maine, and is a retired Army officer. Current research interests include Army special operations during the Korean War, special operations aviation, and World War II special operations units.

Leave A Comment