A Combat First:

Army SF Soldiers in Korea, 1953-1955

Part 2

Above, 8007th personnel, left to right, 1LT Sam C. Sarkesian, 1LT Warren E. Parker, CPT Francis W. Dawson, 2LT Earl L. Thieme and 1LT Leo F. Siefert at Camp Drake, Japan. The men are graduates of Class #3 of the Special Forces Course. (U.S. Army)

Part I — A Combat First

In “A Combat First” Kenneth Finlayson for ARSOF’s Veritas magazine, brings out the details of that inception of PSYOP and SF as enduring institutions within the army. Ultimately, 99 Special Forces men, (77 officers and 22 enlisted soldiers) deployed from Fort Bragg in five groups between February and September 1953. Thus SF began its first combat roles under that name.

By Kenneth Finlayson

From the ARSOF publication, Veritas, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2013

https://arsof-history.org/articles/v9n1_sf_in_korea_page_1.html

The lack of quality equipment did not significantly affect UW operations. At this late stage of the war (mid-summer 1953), the interest in fighting was rapidly waning. The Special Forces soldiers focused on training the PIRs. The large guerrilla presence on the islands figured prominently in the Armistice negotiations. The presence of anti-Communist elements on islands off their coastline particularly rankled the North Koreans. Post-Armistice control of these islands was a contentious issue. Consequently, the U.S and South Korea continued to keep a military presence on the off-shore islands during the discussions.

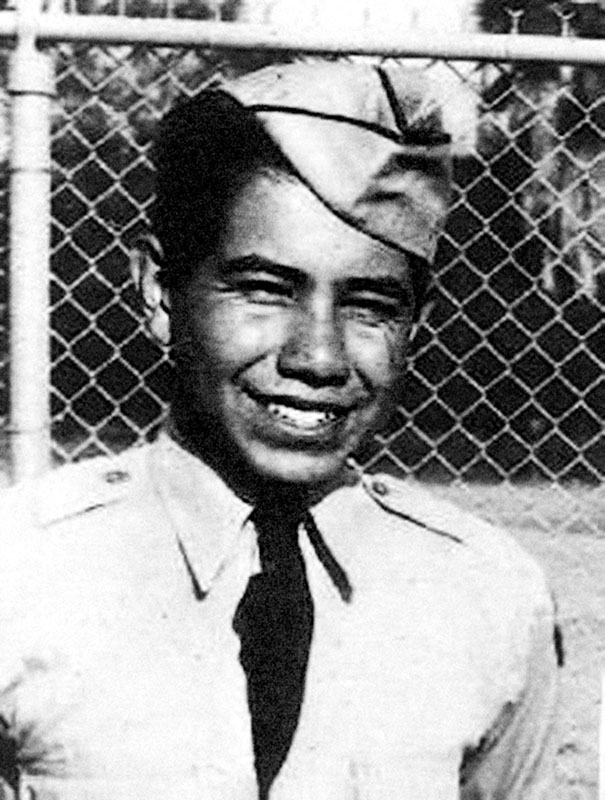

The Special Forces personnel in the first three rotations experienced a higher operational tempo and a greater threat from the Communist forces. Two Special Forces soldiers in the early cycles became casualties during operations in 1953. Infantry 2LT Joseph M. Castro with WOLFPACK 8 was killed on 17 May 1953 while crossing a rice paddy dike during a daylight operation on the mainland. Infantry CPT Douglas W. Payne died on 21 July 1953 when his base on Sui-do was attacked and overrun by North Korean forces. These were the first two Special Forces soldiers to die in combat and the only fatalities among the SF deployed from Fort Bragg. After their deaths, guerrilla command directed American advisors to “use judgment and caution” if accompanying their guerrilla elements during operations on the mainland.32

Those SF who came in the final two levies from Fort Bragg experienced the war’s drawdown. The guerrillas were not interested in being the last casualties of the war. In the months before the signing of the Armistice on 27 July 1953, the number of raids on the mainland declined dramatically. While working with the guerrilla units on the islands was the primary SF mission, not all the Special Forces soldiers ended up as advisors.

2LT Joseph M. Castro was killed while on operations with WOLFPACK 8. He was the first Special Forces soldier killed in combat.

Above left, 2LT Earl L. Thieme (foreground) and an unidentified enlisted man check their map during a reconnaissance northe of Seoul in the winter of 1954.

A number of the SF soldiers were assigned to the guerrilla command Tactical Liaison Office (TLO). Small U.S. Army intelligence teams inserted North Korean and Chinese defectors and some South Koreans on foot through the frontline infantry divisions to collect battlefield intelligence about the enemy in front of the UN units. The experiences of the Special Forces soldiers performing TLO duties were explained in Veritas Vol. 8 No. 2.33 A few SF troops were assigned to the 8007th AU, whose varied missions included the recovery of downed UN pilots, the gathering of information on UN POWs, and the collection of general battlefield intelligence.

“There was very little done to prepare to go; no special training, no advance briefings. Once we were on orders, we got some leave and then reported to Camp Stoneman.” — 1LT Earl L. Thieme

1LT Earl L. Thieme was part of the third group of SF soldiers levied for Korea in March 1953. Trained in the 10th SFG at Fort Bragg, Thieme recalls that “there was very little done to prepare to go; no special training, no advance briefings. Once we were on orders, we got some leave and then reported to Camp Stoneman.”34 When 1LT Thieme got to Camp Drake, Japan, he discovered that he was being assigned to the 8007th AU Recovery Command. Their mission was to gather information on Prisoner-of-War camps in North Korea where Americans might be held. Four other Special Forces soldiers, CPT Francis W. Dawson, 1LT Warren E. Parker, 1LT Sam C. Sarkesian, and 1LT Leo F. Siefert also served with Thieme in the 8007th. “The FEC G-2 gave us the mission. He told us it was Top Secret and to get over there ASAP,” said Thieme.35 At the 8007th headquarters in Seoul, the men got their assignments. The unit conducted agent insertions on both coasts to find and verify Communist POW camps in North Korea.

Landing on many of the rugged islands could be a dangerous operation. The recovery of downed pilots by the 8007th AU often meant landing on island without a prepared dock area. (U.S. Army)

8112th AU Recovery Command Patch

1LT Sam Sarkesian commanded the 8007th AU Recovery Command Team #1. He was sent to Cho-do (West Coast) with a sergeant and two enlisted men.36 His mission was two-fold: to establish escape and evasion nets for downed U.S. and UN pilots, and to gather intelligence on camp locations. Confiscated Korean junks were used to insert agents on the mainland. They were to return to a pre-arranged point after a specific number of days for pick-up. After recovery, the information they gathered would be collected and processed. Most of Sarkesian’s agents failed to return for extraction.37 His area of operations changed after the Armistice, when all friendly troops were evacuated to new sites south of the 38th Parallel.

1LT Reuben Mooradian had to move his guerrillas from Yo-do south to Yuk-do. There he assisted with the training of 1st PIR until leaving for the 77th SFG at Fort Bragg in July 1954.38 As the guerrillas left the South Korean islands, they were replaced by ROK Marine and Army units.

With the signing of the Armistice, 1LT Sarkesian moved his unit south from Cho-do to Paengny?ng-do. From there he continued to insert agents until leaving Korea in March, 1954. “We learned a lot of lessons, but we did not accomplish very much. Unfortunately, the lessons learned were not put into any official documents,” Sarkesian said. “We expended a lot of energy for little result. I wish we had better briefings and training before we went. There was a total lack of coordination.”39 Similar missions were run on the East Coast by other elements of the 8007th.

1LT Reuben L. Mooradian received two weeks of training at the Far East Command Intelligence School before joining the 1st Partisan Infantry Regiment on Yo-do. (U.S. Army)

1LT Sam C. Sarkesian, commander of Detachment #1, 8112th. He was responsible for the establishment of escape and evasion networks and the resue of downed airmen.(U.S. Army)

1LT Warren E. Parker commanded a detachment on the East Coast at Sokch’o-ri. His mission was to gather battlefield intelligence. He coordinated with the Navy to escort his motorized junks during insertions and extractions.40 Parker’s detachment did not train the personnel being inserted. The agents were dropped off shortly before they left on their mission. The 8007th provided security, some supplies, and transported the agents to their insertion point. Some material supplied to the agents was quite valuable.

1LT Earl Thieme remembered several trips to Tokyo to collect gold and wristwatches for the agents going on missions.41 Thieme was assigned through two unit designation changes; 8007th to 8112th on 24 September 1953 and then 8112th to 8157th on 5 January 1955.42 Although airdropping agents behind the lines was discontinued after the Armistice, the ground and sea insertions continued until 1955. The majority of the Special Forces personnel continued working with the guerrillas.

By summer 1953, the Armistice negotiations were almost done. The ranks of North Korean partisans, some of whom had been on the islands since 1950, had been greatly reduced by losses and desertions. Many of the newcomers were South Korean. “The leadership was still people who came out of the north,” noted 1LT Charley Norton, “but the replacements were made up of guys from Seoul and Inch’on who were dodging the ROK Army [draft]. The partisans were a lot better deal.”43 MAJ Richard M. Ripley recalled that, “things were locked in as far as the war went. The guerrillas knew the country was going to be divided in the end, so it was tough to ask them to sacrifice too much.”44 Still, unauthorized raids on the mainland continued after the Armistice, because a handful of Americans could not prevent them.

“When we got there, there wasn’t much of the war left,” noted 1LT Charley Norton. “The Koreans could sense it was winding down. Still, we continued to run operations against the mainland. Usually about ninety partisans would go. This number was dictated by the number that could fit on a fishing [sailing] junk. Usually thirty per junk, with one motor junk pulling three fishing junks. We gave the fisherman rice to use their boats.”45 The raids were against the North Korean Army and Border Constabulary units manning the coast. The advisory mission after the Armistice entailed demobilizing the armed guerrillas, a delicate, complex and sensitive mission.

With the cessation of hostilities, the South Korean government faced the dilemma of assimilating large, well-armed, American-trained guerrilla units composed primarily of North Koreans as well as displaced civilians. The South Korean solution was to assimilate the guerrillas units into the ROKA, an action that involved relocation. 1LT Charley Norton recalled, “The transition was a very messy thing. The ROKs needed to get control, but it took from July 1953 to April 1954 to process the partisans for the transition. They did not replace the U.S. forces [advisors] so we stayed with the partisans, keeping them supplied and trained until the spring of 1954.”46 Some of the guerrilla leaders were given commissions in the ROK Army, which helped maintain order within the units during demobilization and movement off the islands. It was a lengthy and painstaking process that tested the mettle of the American advisors.

Roll call for a guerrilla unit. As 2LT Maurice H. Price found out, the guerrillas would attempt to pad the numbers in formation to get a larger share of the food resupply. (U.S. Army)

Towing a sailing junk. Often one motorized junk would tow three sailing junks on an operation. (U.S. Army)

2LT Maurice H. Price, a Regular Army officer who later served in Special Forces, was assigned in September 1953 as a company advisor in the 2nd PIR on Kyo dong-do. Specifics about the demobilization process were lacking. “Initially, all we had were rumors [about demobilization],” Price said. “Every day one of the NCOs would go to Kangwha-do [2nd PIR headquarters] but there was nothing official at first.”47 The two principal tasks involved getting an accurate headcount for each guerrilla unit and collecting crew-served weapons, pyrotechnics and ammunition before leaving the islands. Neither was easy.

“The distribution of rice was the rationale for the weekly headcounts. It was clear that we were getting inflated numbers,” Price recalled. “Early one morning, one of my NCOs went out with an interpreter while we were holding formation in my company. From a hilltop they watched as one hundred guerillas double-timed across the island after our formation ended to join the other company before we went over to count them.”48 Accounting for weapons and ammunition proved just as difficult.

“The island [Kyo dong-do] once had gold mines and there were small caves all over the place to hide weapons and pyro,” Price remembered. “It took a while to find the stuff and collect it. We had ordnance [weapons maintenance] teams come out and the storyline was that they were there to inspect the machineguns and mortars. In reality, we were getting it under our control.”49 For Price, the advisor role was a mixed blessing. “The training was valuable, but the isolation could be tough,” he said. “Demobilizing the guerrillas was a brutal business. At times you had to be a bald-faced liar.”50 The preparation began in January 1954 and picked up speed until March.

1LT Norton along with Wolfpack 1, (some five hundred guerrillas and families), and the 2nd PIR (eight hundred plus dependents) were shipped by LST to Cheju-do, the primary reception and processing point for partisans transitioning into the ROK Army.51 2LT Maurice Price likewise accompanied his guerrillas south.

“The movement was done in one day from Kangwha-do. It was a contract deal; the [WWII-era] Navy LST had a Japanese crew. Charley Norton and I were the only Caucasians on the boat,” Price remembered. “When we arrived, the ROK Army and Navy were waiting for us. The Good Samaritan stuff ended at that point. Most of the guerrillas were strip-searched when they came ashore.”52 After this mission, 2LT Price finished up his tour as a rifle company executive officer with the 2nd Infantry (Indianhead) Division. He left Korea for Fort Bragg, where he was assigned to the 77th SFG. His experience as a guerrilla advisor contributed to his later assignments in Special Forces. What was missing was a formal program to collect and use the experiences gained by the advisors.

“At the [initial] selection process at Camp Drake, we were told not to expect publicity. It led to the ‘silent professional’ mentality,” Price recalled. “When we were debriefed on leaving the 8240th, we were told not to talk about the tour. They placed heavy emphasis on our not drawing any attention to our experiences.”53 Consequently, the knowledge and lessons learned by these first SF advisors were not disseminated to the 10th and 77th SFGs.

The Korean War was the first employment of Special Forces to a combat theater. All SF soldiers sent to Korea were individual replacements working with other Army personnel detailed to guerrilla elements. No SFOD-Alphas (ODA) deployed to Korea for the war. “There was never any plan to run twelve-man teams,” recalled 1LT Charley Norton. “We could have effectively employed one ODA per regiment, but the teams were all back at Fort Bragg [77th SFG] or enroute to Germany [10th SFG].”54 This was due in large part because, throughout its existence, guerrilla command was never configured along doctrinal lines established in the Army’s Field Manual 31-21, Organization and Conduct of Guerrilla Warfare where the ODAs could have been properly employed.55

The late arrival of Special Forces-trained personnel in the last months of the war makes it difficult to evaluate the effectiveness of the SF training programs. Their commitment to FEC demonstrated that the partisan advisory mission was a valid UW skill. It showed the Army that SF could train indigenous forces to support conventional forces. These same skills form the cornerstone of the Special Forces UW mission today.

The author would like to thank the many veterans who gave generously of their time for interviews and provided the photographs incorporated into this article.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Kenneth Finlayson is the USASOC Deputy Command Historian. He earned his PhD from the University of Maine, and is a retired Army officer. Current research interests include Army special operations during the Korean War, special operations aviation, and World War II special operations units.

Leave A Comment