18D Training Today

Left to right, How Miller, Mike Jones and Lew Chapman (Photo courtesy How Miller)

By How Miller

Imagine, if you will, how excited I was to be invited to tour the Joint Special Operations Medical Training Center (JSOMTC) on my trip to Fort Bragg. Training has evolved tremendously since I became a 91B4S Special Forces Medical Aidman in 1968. Their mission is to merely produce the finest medics in the world.

Thanks to fellow Chapter 78 member, Dennis DeRosia, having invited two head trainers, Mike Jones and Pat Buckles, to join his 91B vs 18D presentation at SFACON 2021 in Las Vegas, they were happy to return the favor and continue the process of highlighting what is on offer for today’s top candidates. My former teammate at A325 Duc Hue in Vietnam, Lew Chapman, and I were treated like extra special VIPs. We helped return the favor with a presentation of what it was like to be a 91B (medic) and 05B (commo man) on an A team at a fun working lunch in their lecture hall.

Dennis DeRosia, center, and along with active duty SWC instructors SFC Michael Jones, left, and SFC Patrick Buckles spoke at the SF Medic Forum at the SFA Convention 2021 at the Special Forces Association Convention on October 24, 2021.

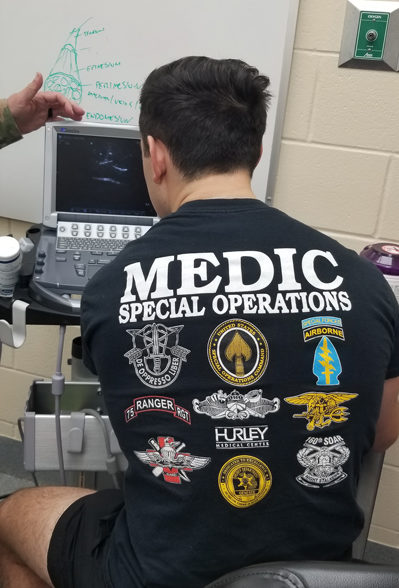

Nowadays this is an integrated SOF training, including providing SOCOM Medics to be Ranger Medics, SOAR Flight Medics, Civil Affairs Med SGTs, and other USASOC Medics, while some will continue on to be 18D Special Forces Medical Sergeants, or Naval Special Operations Independent Duty Corpsmen.

All students go first through the 9-month 68W1 course. That begins with National Registry EMT basic and ends with National Registry Paramedic civilian certification. The civilian certifications are a big improvement for transition back to civilian life after the service. As a 91B in those early days our qualifications were considered more of a state secret, resulting in no civilian authority recognizing our training and accomplishments. That caused many disappointments when trying to build on our experiences when “back in the world”. The 68W1 course culminates in testing for civilian certification in (ACLS) Advanced Cardiac Life Support and (ATP) Advanced Tactical Paramedic, which is a good intro to any medical facility. JSOMTC lays claim to the highest pass rate of any school in the country. In order to maintain the 68W1 MOS, every two years they return for refresher and updates and re-certification.

There are many facets to the training, including many medical subjects, hands-on training, and what we used to call OJT at several civilian hospitals. Experiences at the hospitals can vary from ambulance runs and Emergency Room duty to delivering babies and open heart surgery, depending on what is available when they are working in their assigned areas. There is a heavy emphasis on Trauma care.

A lot of the training is now done online, allowing for students to study and self-test at their own schedule. 100 percent correct answers are required to pass on to the next section (Each block requires a 75% GPA to pass onto the next iteration with an academic review board if you fall under the passing GPA), with reviews available to fill in any info that was missed or misunderstood. The pace of the material is intense, requiring focused attention and good scheduling skills, but this method actually allows for less travel and more studying. The instructors also make themselves available by cellphone or email for an unbelievable amount of time.

For practice, a student starts an IV-on his partner (How Miller)

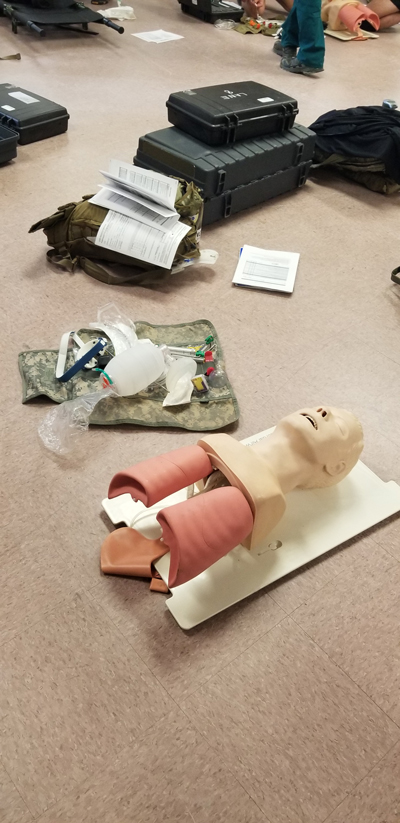

One of the sophisticated manikins used for intubation training. (How Miller)

Our tour started in a very busy training area. Endotracheal intubations and starting IVs were being practiced when we visited one of the activity areas. The intubations were practiced on sophisticated manikins that showed exposed lungs and stomachs.

If one missed the trachea, the stomach would start to fill with air and expose the error. This was done in cooperation with one’s partner. Then the assistant became the intubater. When under fire, this is not an option, so cricothyroidotomies are becoming the go-to choice in combat if an airway can’t be cleared and maintained otherwise. I recall carrying a ballpoint pen in one of my pockets in case I needed to use the empty barrel to keep an airway open. I’m sure they have better ways now.

Starting the IVs was done in a different manner. One partner would actually start the IV on the other, under supervision, and then roles would be reversed and the patient would become the medic. You can imagine that method leads to a lot of care being taken not to hurt the partner in the hopes that he or she will also be that careful. I recall we used that method for lots of procedures, including nasal intubation.

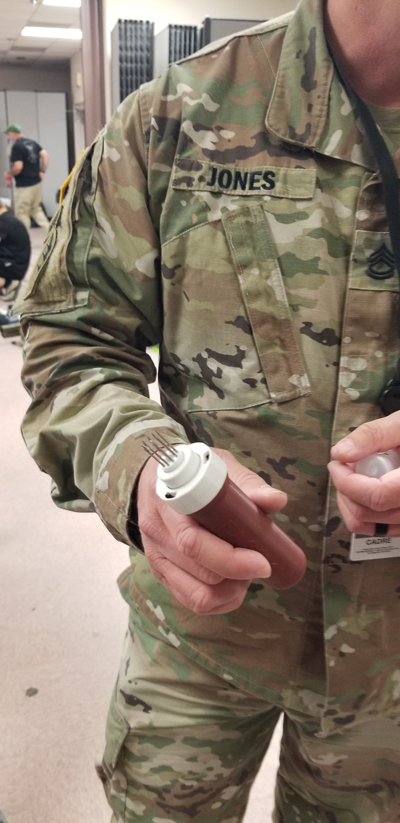

Intraosseous fluid replacement is another innovation that saves many lives. Instead of a medic trying different vein locations to start an IV, which could ultimately prove too difficult to accomplish in the field, some injured soldiers can only be saved by injecting fluids or even blood directly into a bone. The device has a series of spikes along the circumference of the roughly quarter-sized circle, which are only for stability, so it will grab and hold on. In the center is a stiff, large-gauge needle through which the product is delivered.

Intraosseous injector head, affectionately called the “Fast One.” (How Miller)

The force needed to penetrate the bone is provided by the spring-loaded injector. There are a few bones that make for the most feasible sites. The two most preferred are the flat tibial surface along the shin and the sternum. If the soldier is in bad enough shape to need this, it most likely will not seem to hurt as much as it will when being removed. Quite often, the best location will be the sternum because it is easy to reach and provides a stable target.

If you were lucky enough to be selected to be an 18D (Special Forces Medical Sergeant), or an SOIDC (Special Operations Independent Duty Corpsman), another 3 months of Surgical, Dental, Disease and other subjects are in store for you, and could result in you receiving a BS degree. There is even a pathway to earning Physician Assistant credentials later on.

I’m a little murky on the field experiences of an NSOIDC, but I know that an SF medic on an A-team, now an ODA, is as good as it gets. You’re the closest thing to a doctor that many indigenous people will ever see. You can have a lot of responsibility, but you also have comprehensive training to prepare you. You also get all the free ammo you can carry.

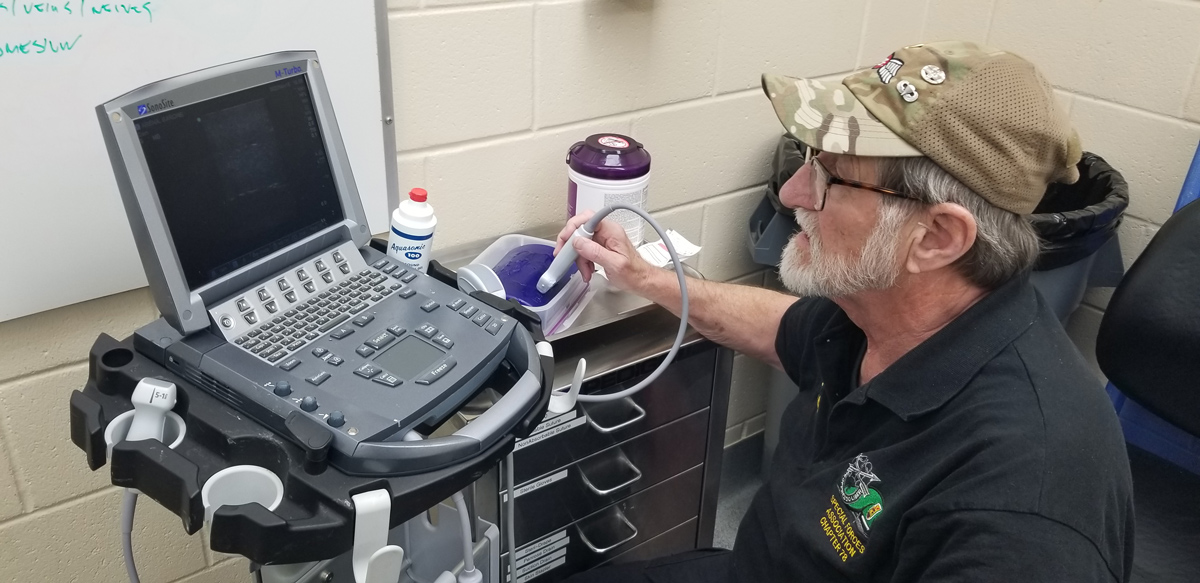

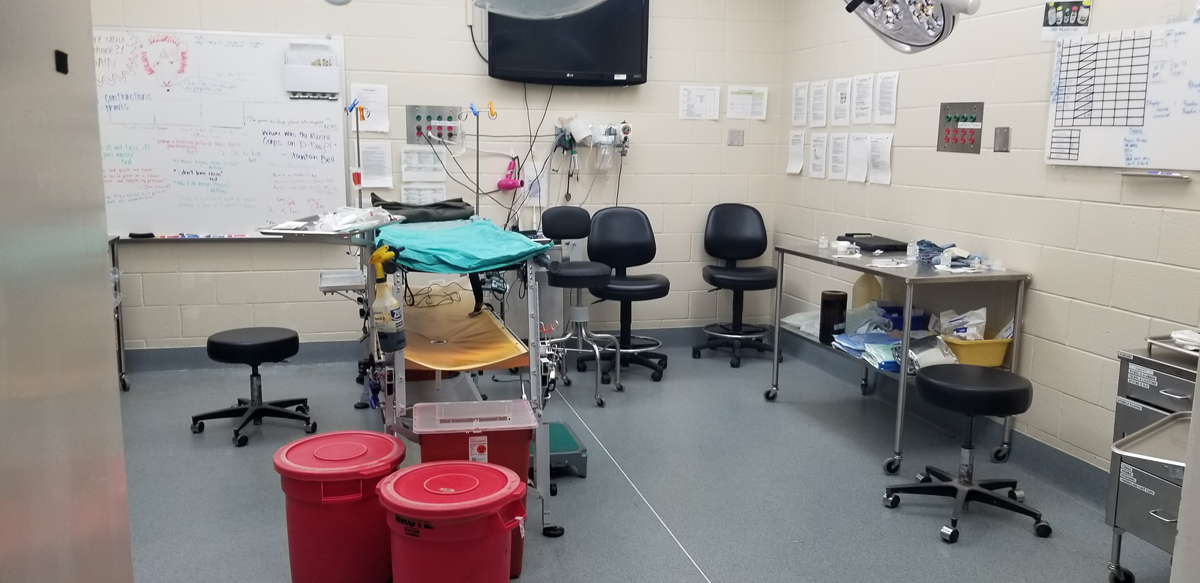

The Surgical section was on a cycle break, but we got to tour the facility and see a couple of the surgical rooms and equipment. The portable sonogram that they use to guide their regional blocks reduces anesthetic use by about 80 percent. There were a few students practicing regional blocks on each other and using the sonogram. When they were done, we got to play with the portable ultrasound as well.

How Miller tries out a sonogram machine. (Lew Chapman)

Regional blocks are a recent addition to potentially lifesaving tools. Besides giving a “local” anesthetic further up the nerves for some surgeries, by knowing the right locations and techniques, a whole area can be numbed, eliminating the need for general anesthesia sometimes. On the battlefield, sometimes a wound can be so painful as to incapacitate a soldier. In some cases, a regional block can numb the pain and allow the soldier to help get himself off the battlefield, freeing up others for a more vigorous defense.

A room in the surgical unit. (How Miller)

When we walked into the lab, which was not being used at the time, I said “Where’s the Lab?”

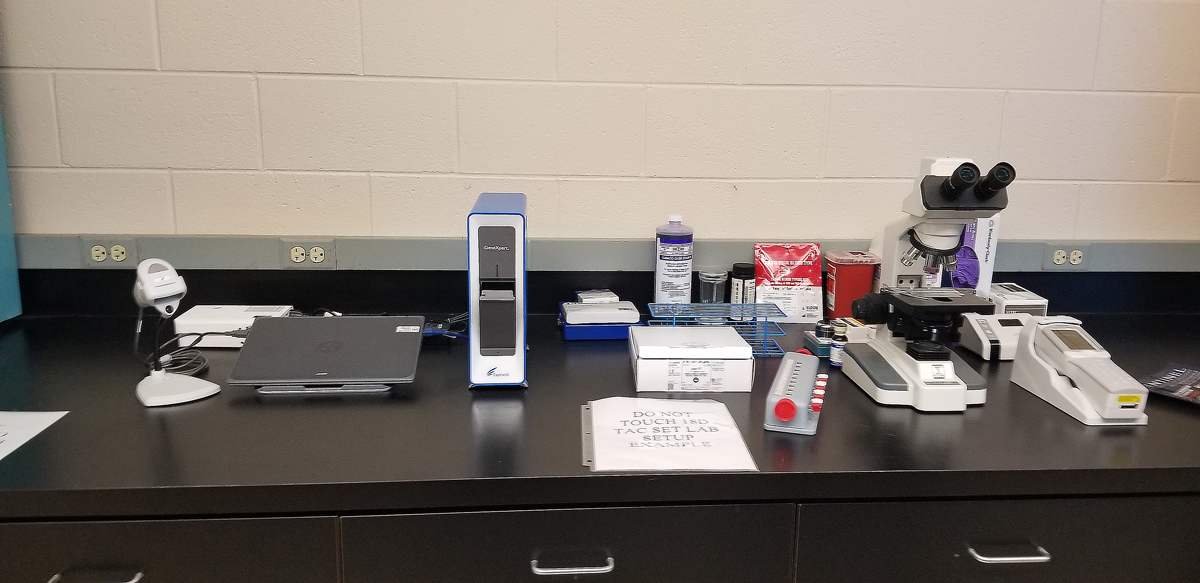

The only familiar things in sight were workbenches, a microscope and a bunch of cabinets. Apparently they still use reagents and centrifuges, but they were packed away, except for those in the ventilation hood. What they use now are a lot of electronic devices that do an incredible amount of analysis of blood samples, for example. They are compact enough to be useful in an ODA lab. These devices are constantly adding capabilities and they are expecting another significant upgrade soon.

Today’s typical lab equipment for blood analysis. Centrifuge not shown. (How Miller)

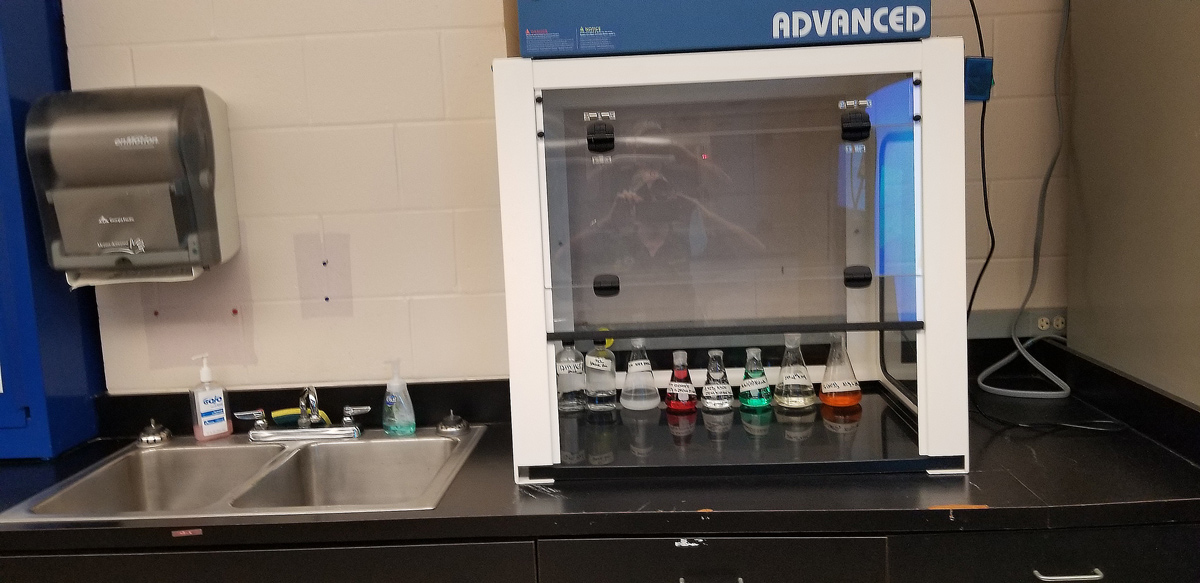

Vacuum hood for reagents.

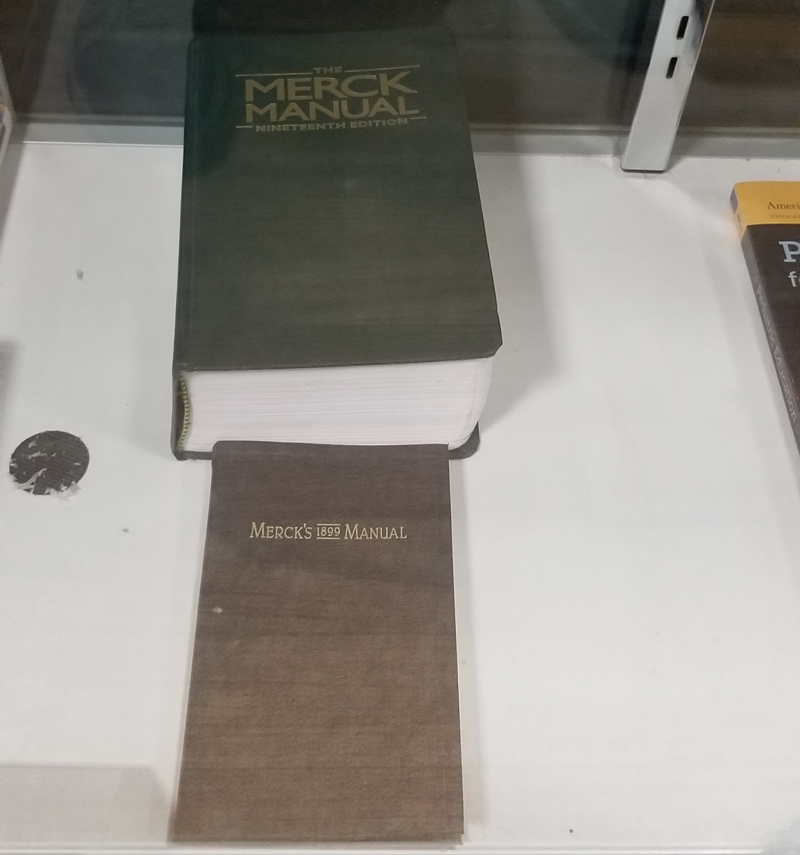

In the hallway were numerous display cases showing the supplies that are typically available for use by the SF Medic. There is everything from syringes and swabs to autoclaves, sophisticated splints, and full kits and packs. I was searching for and delighted to find that the A team bible, the Merk Manual of diagnoses was available. The one we used was the eleventh edition, and a lot of that same information is in the current version.

Some of the available kits on display.

We spent some time looking at the Hall of Heroes, SOF Medics that died in combat. A strong message of how serious the job is.

Later we met with Mike Jones, trainer Mike Jackson, and a group of trainees at Charlie Mike’s Pub. But that’s another story.

Still available to order, the A Team Medic Bible, the Merk Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy (How Miller)

The Hall of Heroes which honors SOF Medics that have died in combat.(How Miller)

About the Author:

How Miller has served as the editor of Chapter 78’s Sentinel since January 2021. Read How’s Member Profile to learn more about him.

I got fired at the Academy of Health Sciences by Steve Bricks Ex for asking the score of the softball game(hell ma’am, I thought if anyone knew it would be you!). I was told to find another job until my advanced course started. So I went to the 600 area at FT Sam and got a job grading Trauma 1 students. Ran every day with SMC Jimmy Jones, Maj Alan Moloff was OIC, and it was a ball! Alan Arline(now DR Arline) wearing his issue swim trunks with one nut hanging out and us laughing our asses off. Rick James was NCOIC and a good friend. At graduation he stuck his tongue in my ear, Bahahahaha. NG tubes were funny as hell, they had a contest to see who could puke the rainbow. It stopped being funny during catheter training. I felt honored to be given a job there. The thing that really impressed me was oral board. Kid from Podunk Tx sits and takes questions from the board, he identified the cause of the illness in this make-believe village, causative bacteria, treatment and prevention. Impressed the hell out of me, and that was 1991.

Rick James now that’s a name I haven’t heard since Ft Sam 93

SF Medics are demigods. There are many circumstances where, forced to choose between an MD and an SF Medic for my treatment, I’d choose the Medic. And this decision harks back to the days when the aidmen were 91Bravos. No offense intended, but it sounds as if the training and the equipment have really ramped up. Appreciate the effort and dedication troops gave and give to become an SF medic.

Graduated the “Special Forces Advanced Medical Training School, Class 67-9 in 29 June, 1967. Complete “phase two 26 August, 1967 as a 91B4S. Off to Vietnam in October, Cai Cai, A431. Out in Mar of 69. went back to college and graduated in 1971 BA in biology. Challenged RN exam in Calif and passed so I became a Registered Nurse. California recognized the quality of SF medic training and if we had “independent duty” as a medic, one was able to challenge the state board exam.

Thank you for this input. I’m currently preparing myself to go into the 18D pipeline if I get selected. been 5 years active army and can’t wait to see what it’s like as a 18D.