16 SF KIA

FOB 4/CCN

August 23, 1968

Larry Trimble with his team ST Rattler. The team was on Marble Mountain on the night of August 23, 1968. They took out the enemy mortars being dropped on the base. Without this the casualty rate at FOB 4 would have been much higher. (Photo courtesy Larry Trimble)

By John “Tilt” Stryker Meyer,

One Zero of Spike Team Idaho

(2021, April 27, sofmag.com, https://www.sofmag.com/17-sf-kias-august-23-1968-nva-through-the-wirefob-4-ccn/)

As the first flare ignited over the camp, Sergeant Patrick N “Pat” Watkins, Jr., made out an NVA soldier standing in the door of the BOQ. “He was wearing a breech-cloth and bandana,” recalls Watkins, and was holding an AK-47. The NVA didn’t see Watkins, who crawled backwards down the hall.

Passing one room, Watkins saw a young officer dead in his bed, impaled by a jagged piece of two-by-four that a satchel charge blew through his chest, literally nailing him to the bed.

Crawling outside, Watkins saw NVA at the TOC (Tactical Operations Center) pouring heavy gunfire into the Special Forces troops trying to awake and counterattack. As he headed toward another BOA, an NVA sapper spotted him and “for some reason…he threw a satchel charge at me instead of shooting me with his AK.”

Watkins rolled out of harm’s way as the sand absorbed much of the blast. When the NVA saw Watkins still alive, “he threw a grenade at me; again, I was amazed that he simply didn’t shoot me. He must have been high on drugs or something, that’s the only thing which explains it.”

Several survivors of the attack felt many of the NVA soldiers were drugged to enhanced their fearlessness.

OJT Pistol Practice

After the grenade exploded, Watkins pulled his .45. “Hell, I had never hit anything with a pistol before. I remember the instructors telling us to shoot low, so I aimed, fired several rounds and finally lucked out and hit him. Talk about miracle hits!”

Still another NVA threw a grenade at Watkins. This time, Watkins was so close to the sapper that he rushed the NVA, knocking him down and taking his AK-47 before sending him to the big rice paddy in the sky.

“After awhile, it all started to run together in my mind. I remember a radio operator named Hoffman, who stood up to go to help one of our guys who was crying for help. He only made a few steps before he was hit. At one point, we had a guy hit real bad who was screaming for help. But, the NVA were using him for bait. Anyone who went to help him was shot or shot at pronto.”

SF medic Sergeant First Class Robert L. “Bob” Scully, “was hit real bad, there was gray matter lying around…we had to get him to the dispensary ASAP.” But the dispensary was on the south side of camp, and the NVA controlled the TOC which lay in between. A medic named Henderson gave Scully an I.V. “I had to put my hand over his mouth to keep him quite, because there were so many NVA,” he recalls. Later, Henderson carried Scully to the dispensary.

“I’ll tell you one thing, the SF medics were their usual outstanding selves. One medic got a DSC for driving around camp, picking up the wounded and getting them back to the dispensary under heavy constant fire,” Watkins said.

This tragic story of the most Green Berets killed on a single day during the Vietnam War had remained shrouded in secrecy for 25 years until this exclusive SOF report.

Sixteen U.S. Special Forces Soldiers were killed 23 August 1968 in the top secret Command and Control North (CCN) outpost in Da Nang when three North Vietnamese Army (NVA) sapper companies executed a well-planned night attack, featuring a daring infiltration into the camp.

Top Secret CCN

The veil of secrecy had remained over this strike for two reasons: It occurred inside the top secret CCN compound, and there were embarrassing breaches in security, without which the attack would not have been so deadly. During a lengthy guerrilla war, even the best of troops and their commanders can become lax, an error the NVA dramatically exploited at CCN.

Only the outstanding heroics of individual Green Berets and some of the indigenous troops assigned to the Recon Company prevented the casualties from exceeding 16.

CCN was under the auspices of the Military Assistance Command Vietnam — Studies and Observation Group (MACV-SOG), which oversaw classified missions run by multiple-service, unconventional warfare troops throughout Southwest Asia, including Laos, Cambodia and North Vietnam.

In Green Berets at War, former Special Forces Captain Shelby L. Stanton notes those special operations also extended into Burma and “Yunan, Kwangsi, Kwangtung and Hainan Dao Island in China.” The majority of the personnel running the missions were Green Berets who were funneled through the 5th Special Forces Group in Nha Trang–the command headquarters for all conventional Green Beret assignments such as A comps along the border, to the top-secret Phoenix project. As men arrived at CCN, they signed formal agreements not to write or speak of these top secret operations for 20 years.

By August 1968, there were six Forward Operating Bases (FOBs): FOB 1 in Phu Bai, between Hue and Da Nang; FOB 2 in Kontum; FOB 4 in Da Nang; FOB 5 in Ban Me Thuot; and FOB 6 in Ho Ngoc Tao, north of Saigon. FOB 3 was in Khe Sanh, which was shut down in June. FOB 3 became Mai Loc.

In 1968, six-man or eight-man Spike Teams and Hatchet Force (company-sized elements of Green Berets and indigenous mercenaries) were launching from the FOBs or their respective launch sites on classified missions, missions that varied from area and point reconnaissance to POW snatches, wiretapping, installation of trail sensors, destruction of NVA fuel lines and attempts to locate American POW camps.

Arch Enemies

By that year, the NVA knew well of MACV-SOG troops. In Laos alone, intelligence estimates were of 40,000 NVA and Pathet Lao soldiers and attached personnel who worked the Ho Chi Minh Trail complex. Part of their job was to attack the MACV-SOG teams.

As far back as 1966 — when mass media in the United States were still reporting it as a civil war — the NVA amassed a battalion attack against the final Special Forces A camp in the A Shau Valley, thus clearing the most significant supply and troop infiltration route into I Corp in the northern sector of South Vietnam. Without that route, the NVA could not have launched the massive Tet Offensive in 1968.

Because of the strategic importance of the A Shau Valley, MACV-SOG placed a premium on targets run in that AO. For Spike Teams assigned to those missions out of FOB 1, they were the most difficult and risky of targets: The NVA controlled the area, there was no friendly artillery support, and the triple-canopy jungle covered steep, mountainous terrain that soared above 5,000 feet in rain forests often cloaked with clouds, thus curtailing or precluding the use of air power.

The menace of the A shau Valley targets was dramatized in May 1968, when an entire Spike Team disappeared and another team was devastated by heavy NVA firepower while searching for the first team.

Whenever the NVA tangled with a MACV-SOG team, they suffered heavy casualties. Thus, the NVA knew the MACV-SOG teams and C&C teams knew and respected the abilities of the NVA. Clearly, the NVA wanted to hurt these elite teams — and hitting them at home would be hitting them where it hurt.

Unbeknownst to SF personnel at FOB 4, shortly after Tet in 1968, the NVA built a sand table of FOB 4 in the Marble Mountain caves to organize the 23 August attack. Marble Mountain was on the south side of FOB 4. Highway 1 bordered the western perimeter; an NVA POW camp was situated to the north of FOB 4/CCN, while the China Sea lapped lazily onto the white sandy beaches of the compound’s eastern front.

The Enemy Next Door

Marble Mountain was honeycombed with caves and trails. South along the China Sea, the beaches were flat. Abruptly, the two rugged peaks of Marble Mountain jutted up, and cradled between them was a pagoda, complete with monks who protested whenever U.S. troops got too close to their holy temple — but apparently didn’t seem to mind having NVA or Viet Cong cadre around.

In support of the conclusion that the NVA had infiltrated agents inside the camp is the fact that the NVA launched this attack when the number of soldiers within FOB 4 had swelled well beyond normal: There was an enlisted promotion board held the previous day; all of the FOB commanders, executive officers and their respective S-3 and S-2 officers held their monthly meetings earlier in the day; that, in addition to the fact the population had grown when the CCN headquarters was recently moved from downtown Da Nang to FOB 4, thus making it FOB 4/CCN.

“By the time the NVA sappers hit the camp, there had to be at least twice, maybe three times as many Special Forces troops in the camp as were normally assigned there,” recalls Watkins, who was in his second tour with MACV-SOG, at that time out of FOB 1, and had appeared before the promotion board earlier in the day.

The spirit earlier that fateful day was “typical of any promotion board gathering,” Watkins said. “There was a lot of drinking, a lot of partying, and general hell-raising” by Special Forces troops. With any promotion board, the drinking was usually heavy because many soldiers hadn’t seen each other for extended periods of time, and at these gatherings, they tended to make up for the months apart during one day’s heavy drinking.

Inside Without A Shot

As America’s elite partied into the night, NVA sappers quietly prepared for their attack. One company dressed in white loincloths, with white headbands and a piece of white material attached to their AKs. The last company wore red.

The NVA troops began infiltrating through the thin wire in the southeast corner of the camp. For months, locals who worked at FOB 4 returned home through the wire. On that night, the NVA marched right into camp, heavily armed and carrying satchel charges.

Sometime after 0100 “all hell broke loose,” said former Green Beret Sergeant Ronald D. “Red” Podlaski. “At first, I though we were taking incoming.” What many thought were incoming rounds were satchel charges exploding throughout the compound.

One company attacked the American recon huts, which sat in three north-south rows on the eastern side of the camp. Another company of NVA hit the TOC, destroying it and damaging the commo center. Other sappers hit the officers’ quarters and transient barracks at the northwestern quadrant.

Podlaski was a team leader in recon company at FOB 4/CCN. The NVA sappers with satchel charges went up to the front door and threw charges into each plywood hut, which housed two to six GIs.

A medic who was staying with Podlaski that night later recounted: “We were lucky. The front door on our hootch had an extra-strong spring on it, so that the door was hard to open… When the sappers came to our hootch, they pulled open the door and threw the satchel charge. But the spring was so strong, the door closed so quickly that the charges bounced off the door and blew up the front steps.”

There was so much confusion and pandemonium that the medic and Podlaski didn’t realize what had happened outside. “Hell, when we ran outside we didn’t realize the steps had been blown away, so we fell ass over head,” Podlaski recalls.

As Podlaski and the medic fell, an NVA sapper opened fire on full automatic, shooting high: “He fired where he thought we were going to be running. If we hadn’t fallen, he probably would have gotten us…Running recon in CCN, we had plenty of close calls in the field,” said Podlaski, who ran more than a dozen targets in Laos and Cambodia during his tour with MACV-SOG, “but I remember hitting the sand and disbelieving that the closest call of all of em was right there in camp, in CCN, when that sapper opened up on us. Unbelievable!”

A South Vietnamese CCN recon team member killed the sapper, as the indigenous troops rallied from their quarters.

Watkins was asleep in the BOQ along the northern quadrant of the camp because the transient billets were packed with people who had gone before the promotion board earlier in the day.

Like Podlaski, Watkins and several of the officers “were awakened by the explosions,” Watkins said. “thought we were taking incoming at first. Then, I realized we weren’t taking incoming and simultaneously, I regretted having given my Swedish K [to a friend] that night.

“All I had was my old Colt .45, which was in my flight survival vest…the NVA had knocked the air conditioners out of the wall and pushed several satchel charges into the building through the holes…”

As Watkins crawled down the hallway, several explosions ripped through the building. He rubbed his eyes in disbelief as he saw two officers looking out a nearby window. “I told the officers to get down on the floor or they weren’t long for this world.”

By then men in the camp began to put up flares, lighting the camp-turned-battlefield.

At some point, an AC-130 Spectre gunship with fore miniguns and two 20mm cannons arrived over CCN.

“Specter did a hell of a job,” Watkins said. “They dropped flares and caught some NVA, in the wire, plus they were able to hit a couple of pockets of NVA in the camp.”

Damage at FOB 4 after the attack (Photo courtesy Larry Trimble)

Good Morning, Vietnam

At first light, Lieutenant Colonel Roy Bahr led a relief force from FOB 1 down the coast of the China Sea into FOB 4, clearing all NVA sappers who had escaped along the beach from the camp after Spectre arrived.

Also at first light, SF troops tracked two NVA soldiers to an outside latrine at the northeast corner of the compound. Accounts of this are mixed: One officer said the NVA killed themselves with a frag grenade; a second account said the SF troops opened fire on the latrine, venting pent-up anger over the carnage wrought by the daring NVA night attack.

Staff Sergeant Robert J. “Spider” Parks returned to FOB 4/CCN shortly after first light. “It was a sight I’ll never forget,” Parks reminisced recently. The road into camp ran from the highway along the northern edge of the perimeter, with turn-offs for the helicopter pad, headquarters, and at the eastern end of the road, for the NCO club, mess hall and Recon Company.

As Parks walked down that road “it looked like a hazy movie scene. There was a haze hanging over the camp–you could still smell the cordite from all the weapons fire. People were running around, some of them still dazed by the night’s tragic events…

“There were still some sappers around in the camp and snipers firing down from Marble Mountain. The NVA fired on the ambulances leaving camp as well as the one pulling in. People in the camp got organized and linked up with the relief force Colonel Bahr brought in from Phu Bai.”

Parks pulled out his camera and took pictures of the dead enemy, including the NVA soldier Watkins killed with his .45. Some are included here.

Later that day, Watkins and several SF and indigenous recon troops went to Marble Mountain and found the sand table the NVA had used to rehearsed their attack on FOB 4/CCN.

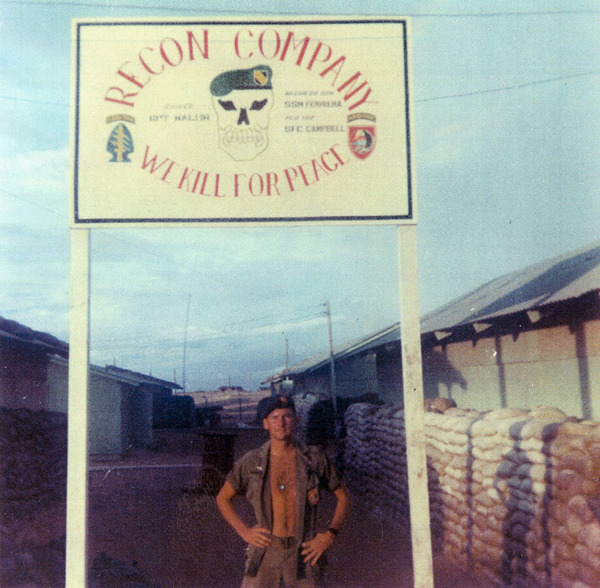

Chapter 78 member Doug LeTourneau standing under CCN’s new entrance sign which he built and put up to replace the sign lost in the attack. (Photo courtesy John Stryker Meyer)

The Enemy Within

There were several facts about the attack which were confirmed by Watkins and numerous survivors interviewed shortly after the FOB 4/CCN massacre:

- “It was obvious they had worked months on the attack…the NVA had good intelligence from inside the camp which helped them pick that night for the attack,” Watkins said.

- Prior to the attack, warning about security problems along the southeast perimeter, where locals walked through the barbed wire, were ignored. Additionally, the local security force appeared to cooperate with the NVA instead of defending the camp. NVA weapons and satchel charges had been cached inside FOB 4/CCN.

- The attack could have been worse: Some NVA troops carried maps which the local Viet Cong had drawn upside down. Thus, they ignored the indigenous recon billets at the southeastern corner of the compound, instead hitting the BOQ at the northern side of the compound. “That was a major mistake, because the recon indig reacted quickly and severely hurt the NVA that night. In ‘68, the indig at FOB 4 were outstanding and they stood tall that night,” Watkins said.

- “We were very fortunate in another aspect,” said Bahr, “because after our commanders meeting, many of us flew back to our FOBs. Thus, when we heard about the attack, I was able to put together the reaction force. We flew down in Kingbees (Vietnamese-piloted H-34s) before first light…otherwise the losses could have been much more crippling.”

- Many SF troops reacted slowly because there was too much boozing the previous night.

- The total of 16 SF troops killed at FOB 4/CCN “was the heaviest USASF loss in a single incident in SF history,” according to Green Beret magazine. Plus, “In the subsequent three days, eight more USASF were killed, six at Duc Lap”–Special Forces A Camp (A-239).”

According to Green Beret, those killed at FOB 4/CCN were:

- Ssgt. Talmadge H. Alphin, Jr.

- Pfc. William H. Bric III

- Sgt. 1st Class Tadeusz M. Kepczyk

- Sgt. 1st Class Donald R. Kerns

- Sgt James T. Kickliter

- Master Sgt. Charles R. Norris

- Sgt Maj. Richard E. Pegram, Jr.

- 1st Lt. Paul D. Potter

- Master Sgt Rolf E. Rickmers

- Spec. 4 Anthony J. Santana

- Master Sgt. Gilbert A. Secor

- Sgt. Robert J. Uyesaka

- Ssgt. Howard S. Varni

- Sgt. 1st Class Harold R. Voorheis

- Sgt. 1st Class Albert M. Walter

- Sgt. 1st Class Donald W. Welch

ABOUT THE AUTHOR — John Stryker Meyer entered the Army Dec. 1, 1966. He completed basic training at Ft. Dix, New Jersey, advanced infantry training at Ft. Gordon, Georgia, jump school at Ft. Benning, Georgia, and graduated from the Special Forces Qualification Course in Dec. 1967.

He arrived at FOB 1 Phu Bai in May 1968, where he joined Spike Team Idaho, which transferred to Command & Control North, CCN in Da Nang, January 1969. He remained on ST Idaho to the end of his tour of duty in late April, returned to the U.S. and was assigned to E Company in the 10th Special Forces Group at Ft. Devens, Massachusetts, until October 1969, when he rejoined RT Idaho at CCN. That tour of duty ended suddenly in April 1970.

He returned to the states, completed his college education at Trenton State College, where he was editor of The Signal school newspaper for two years. In 2021 Meyer and his wife of 26 years, Anna, moved to Tennessee, where he is working on his fourth book on the secret war, continuing to do SOG podcasts working with battle-hardened combat veteran Navy SEAL and master podcaster Jocko Willink.

Visit John’s excellent website sogchronicles.com. His website contains information about all of his books. You can also find all of his SOGCast podcasts and other podcast interviews. In addition, the website includes in stories of MACV-SOG Medal of Honor recipients, MIAs and a collection of videos.

Leave A Comment