THE SLAVER’S WHEEL: Sully in the Congo

By Jack Lawson with Sully deFontaine

Excerpted from The Slaver’s Wheel: A Green Beret’s True Story of His CLASSIFIED MISSION in the Congo, JNM Media (March 22, 2018), Chapters 20-21, with permission from Jack Lawson

Editor’s Note: In 1960, Belgium granted the Congo its independence under pressure from the United Nations, knowing that the country was woefully unprepared and would likely devolve into multi-tribal conflict. Green Beret Sully deFontaine with his small team was sent on a secret mission to rescue missionaries and others from the ensuing ethnic cleansing to rid the country of the hated white colonists. All manner of horrors awaited those that were to fall victim.

The “Slaver’s Wheel” lays out the situation and the effectiveness of the mission. These two chapters suspensefully tell of just one incident from the mission. The whole book is well worth the read.

Standoff

Robert One, this is Robert Four, come in!” Frenchy’s voice crackled over the radio from the small airport at Coquilhatville to where Sully had moved the team. The call awakened Sully, Clement and Mazak. Sully looked at his watch; it was 4:45 in the early morning hours of July 19, 1960. He shook his head in disbelief.

Sully leaped off his cot and grabbed the radio handset. “This is Robert One, go ahead Robert Four,” he answered.

“Robert One, I just had a call from a group of people in Gwante calling for help. It sounds like they’re in real trouble. I’ve confirmed twelve people including nuns, a priest and some missionaries. The message was weak, but he made it clear that his missionary outpost is under attack by a large group of rebels. The rebels are threatening to kill them.”

“Robert Four, did you tell them to mark their location with a white cross or flag?” “Affirmative, Robert One.”

“Okay Robert Four, we’re on our way!” Sully relayed. “How the heck did Frenchy pick that call up at this time in the morning?” Sully wondered aloud, shaking his head in disbelief.

“He’s sleeping with his headset on!” Clement said chuckling.

As only one aircraft was available in Coquilhatville, Sully and Mazak took off in it, heading toward Gwante.

Sully left instructions with Captain Clement that as soon as another aircraft arrived at Coquilhatville from Brazzaville, it was to be immediately refueled and he was to fly out to assist them.

Despite seeing no flag or marker in the area of Gwante or any building resembling a church or mission, the pilot set the aircraft down on a dirt road bordering the village to conduct a search. Sully got out of the plane with two hand grenades concealed in his pockets while Mazak covered him with a submachine gun. Sully briefly searched the village and found no one. Still concerned that the people may be in hiding, Sully told Mazak to search the village further while he proceeded to search from the air.

When Sully left him at Gwante, Mazak was carrying a medical backpack, a radio, grenades, a submachine gun and more ammunition than most Special Forces soldiers would take with them. It was like Mazak had once confided to Sully: “I always carry one more knife, one more grenade and twice as many magazines as the guy next to me. That’s how I’ve stayed alive this long.”

Mazak was to radio him if he found the evacuees at Gwante. After flying ten miles east of Gwante, Sully caught a glimpse of a white flag fluttering from a church steeple in the neighboring village of Mombaka.

The pilot landed on a narrow road leading into the village, the tree branches on the sides of the road scraping the wings. Coming to a stop in a clearing about a hundred yards from the church, Sully got out, and the pilot turned the aircraft and readied for takeoff.

Outfitted in his British safari suit and armed only with the two concealed grenades and the pistol in his medical bag, Sully approached the church. A middle-aged priest with snow-white hair ran toward him. His smock was drenched in blood, his face was bruised and cut, and one eye was swollen shut.

“Are you who I radioed for help?” he asked Sully. “Yes, I’m Robert. Where is everyone, Father?”

“In the church. Come this way,” the priest said. He beckoned as he turned and both men hurried to the church door. The priest took Sully aside and described their ordeal.

“When the rebels came into the village we barricaded ourselves inside the church, but they broke in and beat us for it. Six of the women are sisters of this church. All of them and others have been abused by the rebel soldiers. I am afraid that some will not live very long. They’re all badly in need of medical treatment. We have bandaged them, but I think two of the elderly sisters have internal hemorrhaging.”

Sully handed the priest his medical backpack, telling him to do the best he could with what was in it and that he would try to radio for more help from Coquilhatville.

The priest told Sully that he believed there were about a hundred rebels terrorizing the village. He also reported that the commander of the rebel forces had said he would return to kill the priest and the others. They had tried several times to get out of the village and escape into the jungle, but were chased back each time.

Calling for Help

Sully heard the sound of rifle and machine gun fire close by and, realizing that he had little time to spare, called the pilot on his radio handset.

“Jake Nine, this is Robert One, come in.” Sully received no answer and called again, “Jake Nine, this is Robert One, come in please!” There was silence. He called again, ‘’Jake Nine, do you read me?”

This time the message from Jake Nine was garbled. Sully called for Mazak.

“Robert Three, this is Robert One. Come in.” Sully called Mazak and waited, but received no answer. “Robert Three, this is Robert One. Come in, over,” Sully repeated.

“Robert One, this is Robert Three, I read you but your signal is two by four,” meaning Mazak’s reception was poor. Sully suspected there was something wrong with his radio.

“Robert Three. I’ve found the evacuees. I’m at Mombaka, ten kilometers due east of Gwante. Have the Belgians send a platoon of Para Commandos immediately, and I need another plane here as soon as possible. My radio is on the blink. Have Jake Nine land the plane now. The situation here is not going well. Do you copy?”

“Roger, Robert One. I read you. I’ll radio Jake Nine and the Belgians in Coquilhatville immediately!”

“Are they sending help?” the priest asked.

“Yes,” replied Sully. He turned to the priest and told him the plane would have room for only six passengers. “Get the sisters ready to move. We’re going down by the road to load those injured the worst on the plane. But the rest of us will have to go into the jungle and hide until more help can get here.”

Sully organized the small group of refugees, moved them out of the building and down the road to where the aircraft would land.

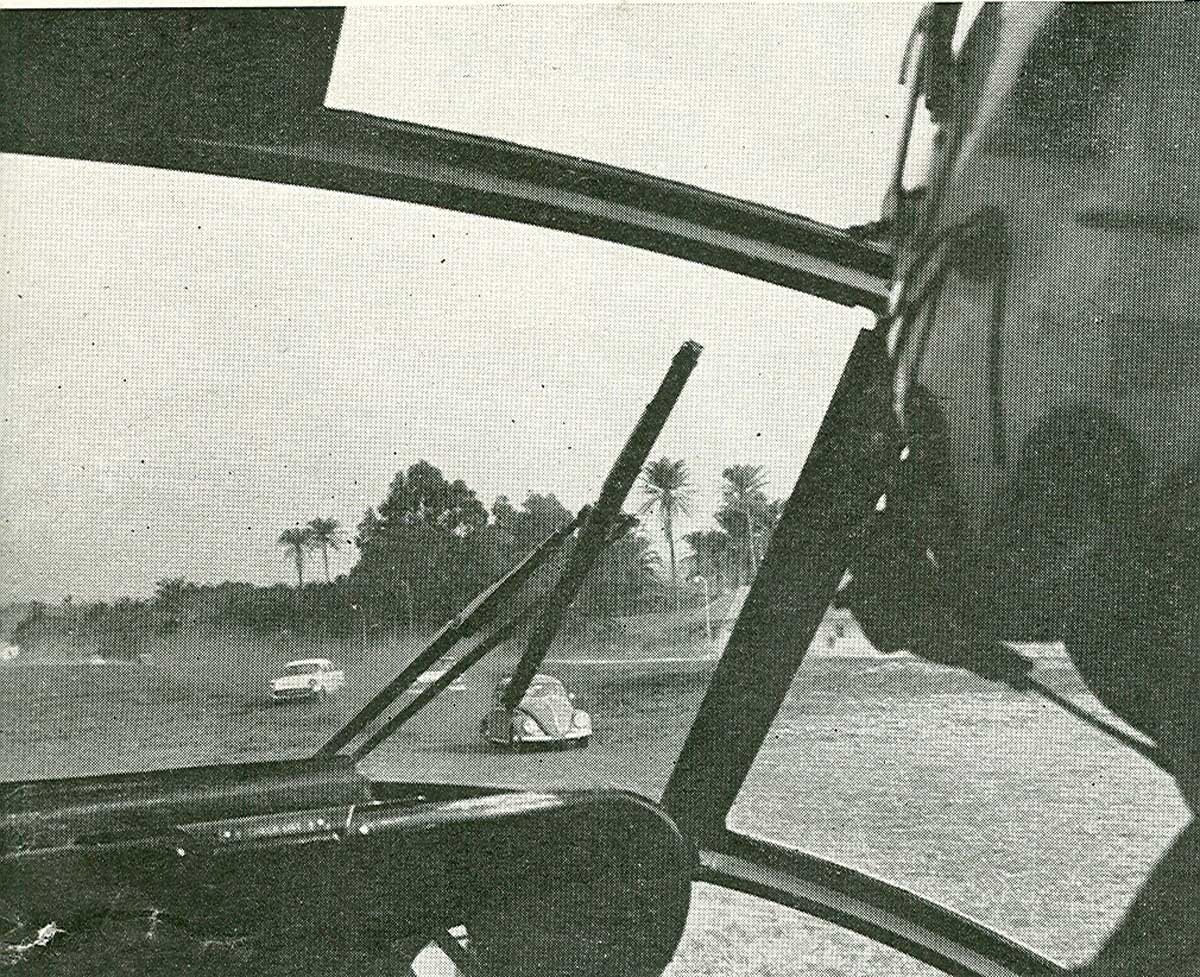

American Congo Missionaries, who had been hiding from rebel soldiers for days, drive madly for the U.S. Air Force rescue helicopter after finally contacting authorities by two-way radio, desperate for evacuation.

U.S. Air Force Pilot George Meyers runs back to his helicopter with the people of Vanga, Congo in pursuit. The other pilot and captain Albert Clement, U.S. Army Special Forces, are running alongside him to the left out of camera view.

Evacuees scream from the aircraft door at other refugees to hurry to the aircraft. Not shown in this picture are the rebel soldiers and villagers racing towards the rescue helicopter to attack them.

A cloud of dust stirred and the engine loudly droned as Jake Nine landed his plane and turned it for takeoff. Sully sprinted to the plane and, over the engine noise, yelled instructions to the pilot.

“Jake, my radio is not working. I’m going to put some of these people on your plane. Get them to the hospital in…” “Robert, behind you!” Jake Nine yelled to Sully, pointing.

Sully turned to see a horde of rebels charging toward them from about a hundred yards away. They began firing their weapons in the air as they ran toward the evacuees.

“Get airborne now, Jake!” Sully yelled, quickly closing the airplane door. The pilot gave the aircraft full power and was airborne in a matter of seconds.

Sully raced back to the priest and nuns as the rebels came closer.

“Kill the whites! Kill the whites!” he heard them chanting. The words would be etched indelibly in his mind.

A surge of adrenaline hit Sully. He placed himself between his evacuees and the heavily armed approaching rebels. In addition to rifles, pistols and machine guns, each one of the rebels carried a machete. The rebels continued toward them, firing recklessly at the plane and into the jungle. Sully quickly turned his medical bag displaying the Red Cross toward them. The group’s charge slowed when they saw the Red Cross, and they came to a stop in front of the refugees. The petrified refugees crowded behind Sully in search of some mental comfort for protection.

Sully and the Commandant

Sully singled out a tall Congolese who appeared to be the leader of the group. Sully approached him speaking in French and Lingala. “I’m Robert. Are you the commandant?”

“I am Major Kimba,” he said to Sully in Lingala.

“Could we talk over here?’’ Sully said, gesturing to a place away from his rebels, not wanting them to hear the conversation. “You will address me as Major Kimba!” the major barked, glaring at Sully. The major appeared intoxicated and reeked of alcohol. “Of course, Major Kimba,” Sully replied.

“That is better,” the major said with a smirk. “Could we talk alone Major Kimba?”

The major began laughing loudly. ‘’Yes,” he said, “but it will make no difference.”

“Major Kimba, I’m a French-Canadian and here to help these people with their medical needs. These people desperately need medical attention. They need to be taken to a hospital. Then they will be no problem to you,” Sully said, as the two began slowly walking away from the rebels.

“They will not need medical attention in a short time. They will not be a problem much longer. We are going to kill them,” the major said, laughing loudly.

Sully, in his bush hat, safari shorts and shirt, looked every bit the neutral French-Canadian medical officer, but it had little impression on the rebels. As they strolled away from the rebels, Sully quickly surmised that any further pleading would get him nowhere, as he suspected the rest of them were also intoxicated. Worse, Sully suspected his request for mercy would get him killed along with the people he was there to rescue.

As they came to a stop, Sully calmly removed a grenade from his vest, straightened the ends of the pin and pulled it from the grenade in front of the major’s eyes. Holding the fly-off lever down to prevent the grenade from exploding, he grabbed the major’s hand, put the pin in it and closed the major’s fingers over it. All Sully had to do was release the grenade from his hand, the lever would pop off and the grenade would explode in seconds. Sully figured he could create a standoff and buy them enough time for help to arrive.

“You know what this is, don’t you Major Kimba? If you do anything more to those people or if you kill them, you will die with them,” Sully calmly told the major.

The major, a former corporal or sergeant in the Belgian Congo Army, was well acquainted with the powerful explosive device Sully held up to his face. The major opened his hand and stared in horror at the grenade pin he held, and then looked at the grenade Sully was holding. The rebels behind him saw the grenade and began to panic, moving away.

“Don’t move!” the major yelled to his men.

The major started to move away in an attempt to run, but Sully grabbed him by the front of his shirt, thrusting the grenade right by his nose and slowly starting to release his grip on it.

“If you try to get away get away from me Major Kimba, I will shove this grenade down your pants!”

The petrified major’s eyes bulged as he wet his pants. He yelled again to his troops, “Shut up and don’t move a muscle!”

A tense, two-hour standoff followed, marked by silence and the periodic punctuation of rebel troops yelling and firing their weapons into the air. Each time the rebels became unruly, the major begged them to stop.

The American MK II Al “Pineapple” fragmentation grenade Sully was holding weighs only twenty ounces. But after holding the grenade for two hours in the midday sun and drenching humidity of Central Africa, it began to feel as if it weighed a hundred pounds.

Sully changed the grenade from one hand to another, but each minute passed like an hour. Pushed to his limits, Sully was wondering how much longer he could continue to hold the grenade. Major Kimba was starting to lose control of his troops.

As adrenaline coursed through Sully’s veins, his head began to ache. He was beginning to feel that his threat was going to fail. He could hear the rebels talking among themselves about shooting Sully, Major Kimba and the refugees. Over and over, he thought, “Where are the Belgian troops?”

Just after Mazak talked to Sully, he told Frenchy to contact the Belgians at Coquilhatville to send help. Mazak’s and Sully’s handset radios were not powerful enough to allow them to talk directly to anyone but Jake Nine or Frenchy, and Sully’s radio was no longer working.

“Robert Three, they’re going to airdrop a platoon of Para Commandos into the Mombaka,” Frenchy said, relaying the Belgian captain’s message to Mazak.

“Tell him to forget the air drop, Robert Four. His men will be too vulnerable to ground fire from the rebels. Just tell him to send them in one of the Otters. Have them stop in Gwante to pick me up on their way.”

“Roger that Robert Three!” Frenchy signed off. A few minutes later, Frenchy radioed Mazak again.

“Robert Three, this is Robert Four. The Belgians can’t pick you up, and they can’t get to Sully for an hour. Do you copy?”

“Roger, I copy. Tell the Belgians to forget it. Send an Otter directly to Robert One’s position! I’m heading to Robert One on foot,” Mazak said.

Jungle Monster

Sully’s safari jacket was drenched with sweat. It had been more than an hour since he’d pulled the pin on the grenade and started the standoff. Most of the women were in urgent need of medical attention. He was now worried that they would die if they stayed out in the baking sun much longer without water. Sully did not dare take the chance to move anyone; the standoff was on a razor’s edge.

The major was as scared as if the devil himself were standing in Sully’s boots. His troops were growing agitated as the situation moved into the second hour.

“Major Kimba, if you order your troops away from here and come with us, I will release you as soon as we’re far enough away,” Sully said in a low voice.

“I don’t know how much longer my troops will take orders from me. You heard them talking,” he whispered to Sully. “They are discussing killing everyone, including me!”

Mazak knew from the radio transmission that Sully was in dire straits. The life of his commanding officer was in peril, along with the evacuees.

“Robert Three, this is Robert Four,” Frenchy’s voice crackled over Mazak’s radio.

“Go ahead, Robert Four.”

“The Otter just got to Coquilhatville. They’re refueling now, but it will be about another hour before they get to Robert One.”

There was silence as Mazak pondered what to do. He could wait an hour for the Otter to pick him up and fly to help Sully or he could run there. The jungle was thick and virtually impenetrable, but Mazak remembered seeing a machete in one of the villager’s huts.

“Robert Three, do you copy?” Frenchy asked after no reply.

Mazak replied, “Robert Four. Send the Otter directly to Mombaka. I’m moving there on foot.”

At that, Mazak ran to the villager’s hut, grabbed the machete and then ran east on the road for about two kilometers until it turned sharply north. He tightened his webbing straps and set off into the jungle.

A few kilometers into the jungle, Mazak began to wonder if he’d made a mistake. He was chopping, hacking, tripping and falling but moving slowly through the thick jungle bush toward Mombaka. He drove himself mercilessly, fearing he would not get to his commander in time. He was soaked with sweat and covered with vines and green slime from the jungle foliage. The worst of it was the “wag a rukkie” bush, so named by South African Afrikaners as it literarily means “wait a moment.” Its hook-like, needle-sharp thorny seeds tear clothing, lacerate the skin and then break off under the skin’s surface. After a few days each seed begins to ferment, creating an infection until the seed pops out simply from touching the skin. It leaves a horrendous hole. This is Mother Nature’s African way of propagating itself.

Just as bad was the buffalo bean. The brown, bean-like seeds hang from trees and have prickly hairs that shoot into the skin causing days of relentless itching. Amazingly, water buffalo virtually subsist on this bean in parts of Africa.

Mazak saw the tails of a dozen venomous snakes slithering away from him as he fought his way through the dense vegetation. The odd thought of how many snakes had struck at him but missed flashed through his mind.

Finally, Mazak saw the signs of village life come to view in the form of jungle paths and trees that had been chopped down for firewood. He picked up the pace and soon was on the outskirts of Mombaka. As he approached the village he looked up and saw two aircraft circling. He bent down and cautiously observed the area. There was no one in sight, but he knew something had gone wrong.

Exhausted, but moving in a crouched position, he made his way to the edge of the jungle and peered through the thick foliage. He spotted the group of rebels and the tiny band of refugees facing each other on the road with Sully and a big Congolese man standing between them. Mazak crept around the rebels alongside the road until he was in a position behind Sully.

He quietly maneuvered himself even closer to Sully’s position. He peered through the thick vegetation to see Sully threatening the largest of the Congolese with a grenade. Mazak’s clothes were ripped, he was drenched with sweat, out of breath and his mind raced, contemplating his next move. Just then the rebels pulled out their machetes and began advancing toward Sully.

“Stand still!” Mazak heard the officer yell at his troops.

This time they did not obey their commander’s orders but continued moving toward Sully and the refugees.

As one hour grew closer to two, Sully knew his repeated threats were losing effect on the rebels. The other plane had arrived about five minutes earlier and was circling overhead alongside Jake Nine’s aircraft. The rebels became increasingly agitated on sight of the second aircraft and intensified their threats and shouting. Sully’s hands were aching from holding the live grenade. It felt as though an eternity had passed since this started.

Each time the major had tried to move away from Sully, Sully pulled him back between the evacuees and his troops, again threatening to detonate the grenade. The hot sun had taken a toll on everyone. Sully silently cursed. Where the heck were the Belgian troops? He changed the grenade from his left hand to his right hand one more time and began to recite a prayer in his mind.

‘’Stand still!” the major shouted in a last feeble attempt to control his troops. Sully watched as the rebels drew their machetes and slowly moved forward. He knew that they were seconds away from the rebels killing the major, himself and the refugees in the most gruesome way. As they drew upon them, the priest began to pray out loud. Everyone knew the final moment was near.

A Rustle in the Undergrowth

Just when Sully thought all was lost, he heard a rustle in the undergrowth next to the road. The clamor turned into a tremendous thrashing sound as a filthy Sergeant Stefan Mazak sprang from the undergrowth to Sully’s side and fired a burst from his submachine gun in the air. He was spewing foul language that Sully knew could only come from former French Foreign Legionnaire Stefan Mazak.

Sully released his grip on the major who ran screaming toward his men. As physically drained as he was after the standoff, Sully threw the grenade he’d been holding into the middle of the rebels. The explosion was deafening. Taking the cue from Sully’s action, Mazak leveled his weapon and fired directly into the rebels. The rebels who weren’t killed or wounded ran for their lives into the jungle, more frightened from their superstition of this “thing” than the gunfire.

Mazak was a fearsome sight and almost unrecognizable to Sully. His clothing was torn, his face and arms were bathed in sweat mixed with dirt and blood, and he was draped with vines as if they were growing from him. He looked like a jungle demon out for vengeance, as he cursed and fired his submachine gun in every direction.

As Mazak changed magazines and fired into the retreating rebels, Sully pulled the second grenade from his pocket and threw that too, then grabbed his pistol from his backpack. The rebels were tripping over their dead and wounded trying to get away.

Shrapnel from one of the grenades hit Sully in his thigh and hit Mazak in the midsection of his back. Fortunately, they were only flesh wounds. Mazak, still screaming torrents of abuse, chased off the rebel soldiers. He returned to Sully’s side where they both faced the retreating rebels, shooting at any who paused to fire.

Sully turned to Mazak and told him in French, “Good God, Stef, you were the last person I thought I’d see!” Sully grinned at Mazak’s appearance.

“You look like you’ve been to hell and back. You got here just in the nick of time, Stef. I thought we were finished.”

“Sorry I took so long to get here. The plane and the Belgians were going to take so long. I finally decided to come here on foot.”

“Stef, my radio isn’t working. Give me yours. I’ve got to call the planes in before these guys regroup and come back.”

Mazak pulled off his backpack and handed his radio to Sully.

“Jake Nine, this is Robert One, land immediately. Who’s the other Jake up there?”

“This is Jake Three, Robert One. I’m flying the Otter.”

“Well it’s sure good to hear from you again, Jake Three. I want you to land after the Beaver takes off. Do you copy?”

“Roger that Robert One. Quite a show you guys put on down there. Best fight I’ve seen in a long time. I would have paid big money to see that, but I had free ring side seats up here!” Jake Three laughingly said.

The pilot of the Beaver landed, and Sully put the worst injured of the evacuees on board his plane. After they took off, Jake Three landed the bigger Otter.

Sully smiled and chuckled at Mazak’s ragged appearance. Mazak started laughing too as he peered down at his clothes. He noticed the blood running down Sully’s leg.

“You’ve been hit, Sully!” Mazak exclaimed.

“I think it’s just a flesh wound Stef, probably from one of my grenades.”

“Think I caught some of it in my back too, Sully.” Sully looked under Mazak’s backpack.

“I can’t tell Stef, you’re covered with so much dirt and sweat. I’ll look at you on the plane. Let’s get out of here.”

With their guns trained on the jungle, they retreated toward the last plane. Miraculously, none of the hostages had been hit by the rebel’s gunfire. Just before he got on the plane, Sergeant Mazak fired one long burst from his submachine gun to keep the rebels’ heads down and give the plane time to take off.

Mazak had been hit in the back by shrapnel. Sully bandaged Mazak’s wound and his own as they flew to Coquilhatville.

I saw you holding the grenade up to that guy’s face, that’s pretty crazy, Sully!” Mazak said.

Sully laughed.

“I got the idea from Jack Hemingway, Ernest Hemingway’s son. When we were in France in World War II, he told me he got into a dispute with the Communist leader of the French resistance movement. This guy refused to have his men surrender their weapons like the anticommunist French Partisans had done after the war was over in France.

“The Allied High Command had ordered Jack to meet with the Communist leaders to demand the surrender of their weapons also. They met in a small house and the meeting turned into an argument where the Communists pointed their weapons at Jack. Jack pulled the pin on a grenade, threw the pin on the table in front of the Communists and said, ‘If I’m going to die, everyone will die!’ Jack held the grenade out in front of the Communists threatening to drop it on the table if they shot him. They agreed on the spot to turn in their weapons. They thought he was crazy!”

Mazak laughed. “I’ll have to remember that one the next time I’m outnumbered!”

The Flight to Coquilhatville

On the flight to Coquilhatville, one of the elderly sisters incoherently repeated her ordeal of being assaulted by one of her fourteen-year-old choirboys. She told Sully that the boy had taken part in mass for years but had joined Lumumba’s rebels in “ridding the Congo of the foreign devils.”

Upon their arrival at Coquilhatville, Belgian Army medics were swarming around the Nuns and Priest attending to their many cuts, a few fractured bones and abrasions.

Despite their hasty first aid bandages, both Sully and Mazak were still bleeding from their wounds. There was so much blood on the plane and on everyone’s clothes, the medics just assumed Sully and Mazak picked it up from their passengers. Both their clothes were soaked with sweat and Mazak was covered in slime and dirt from his run through the jungle.

Seeing Mazak crouched down and in obvious pain, but redressing Sully’s wounded leg, two Belgian medics scurried over to attend to them. Sully had been struck in the lower leg by grenade shrapnel or a bullet. Whatever it was, it had gone straight through his leg without hitting a bone, the medics told him, as they bandaged his wound.

Mazak was extremely lucky. A piece of shrapnel had struck him in the back, just to the left side of his spinal column, hit one of his ribs and glanced off after ripping holes in his safari jacket and tearing a horrendous looking chunk of his skin off.

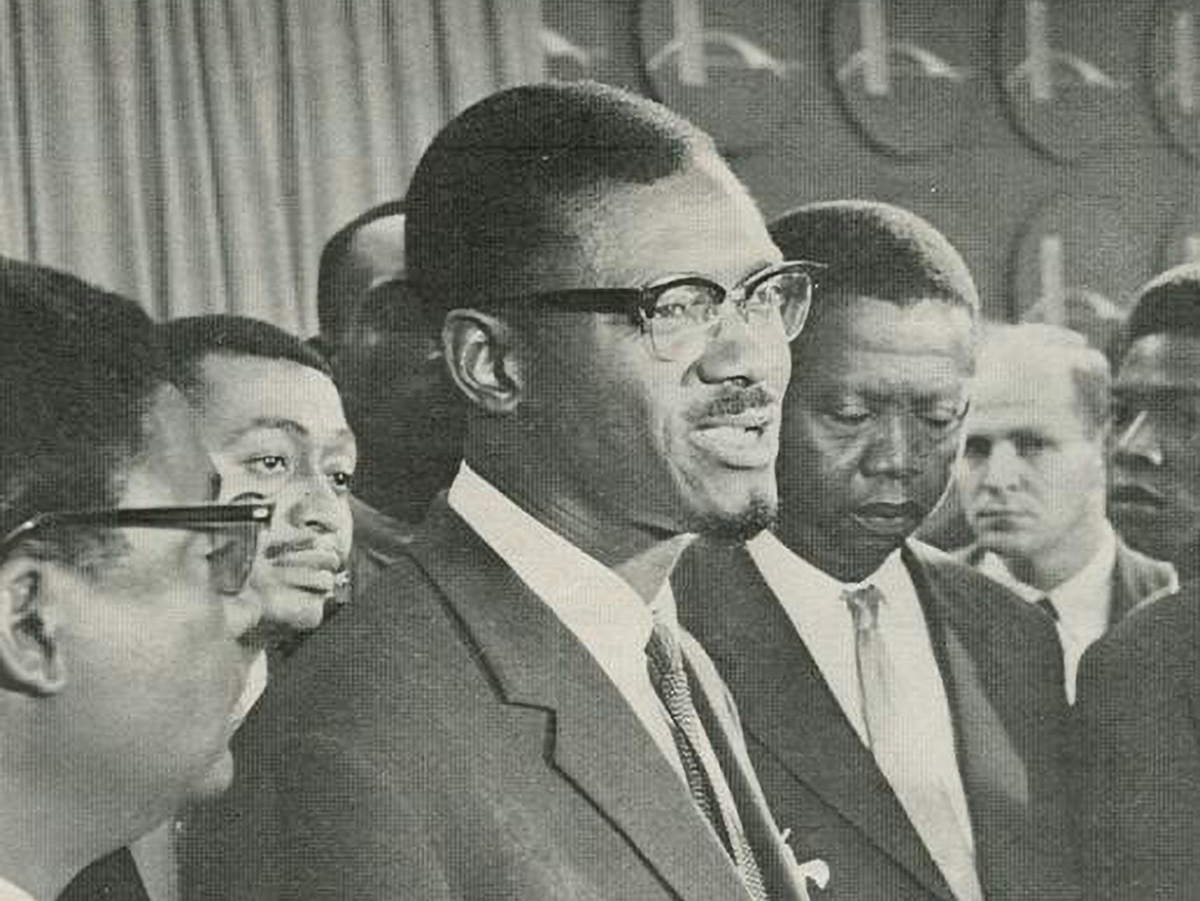

Patrice Lumumba at the 1959 Round Table Conference in Brussels.

On July 20, 1960, Sully was informed that Belgian troops were to depart the Congo in three days. The United Nations peacekeeping troops had arrived, but they were ineffective against the rebels. Tensions mounted between the Congo rebel army and the UN troops, and the situation was deteriorating rapidly. Even the UN troops fortified their positions and isolated themselves in their compounds whenever possible.

The day after the standoff with Lumumba’s rebel soldiers at Mombaka, Sully encountered Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba for the first time at Coquilhatville. Lumumba looked far from being the man responsible for so much bloodshed and for fueling the fire of anti-foreign sentiment among the Congolese.

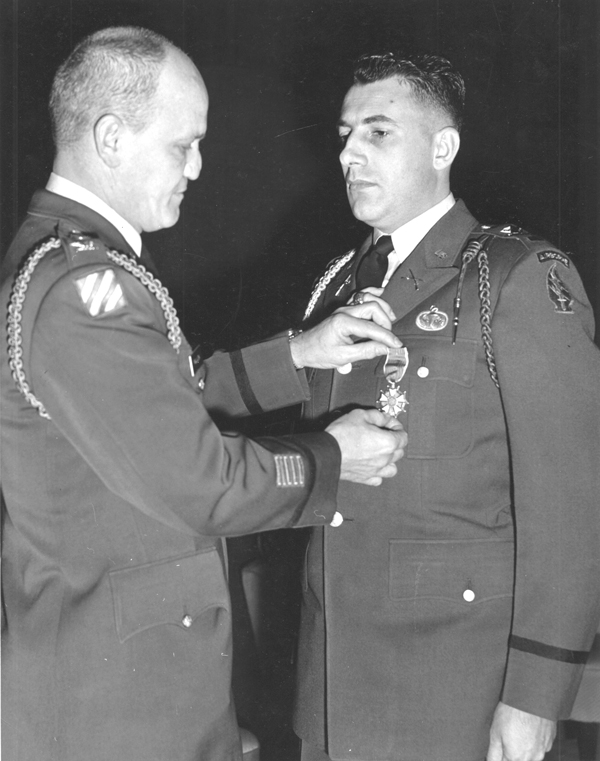

Sully deFontaine received the Legion of Merit from Colonel ‘Iron Mike’ Paulick, Commander of the 10th Special Forces, in a secret ceremony at Bad Tölz, Germany. At the time of this action, the political situation in the world was such that regardless of their use of force in defense of themselves and their evacuees, the sensitivity of Special Forces personnel engaged in combat operating in the newly independent former Belgian Congo would have had severe political repercussions and caused great embarrassment to the United States.

Because of the classified nature of this operation, only a small secret ceremony was permitted. The citations awarded gave the appearance that this operation was part of a peaceful United Nations mission, which it was not. The United Nations came in after this mission’s conclusion.

At Mombaka, Sergeant Mazak received shrapnel wounds to his spinal column from a grenade explosion which he recovered from after receiving treatment from Belgian Army Medics at the Belgian held airstrip at Coquilhatville, Congo. Sully deFontaine was wounded either by a bullet or grenade shrapnel passing through the calf of his leg during their furious fire fight and was also treated by Belgian Army Medics.

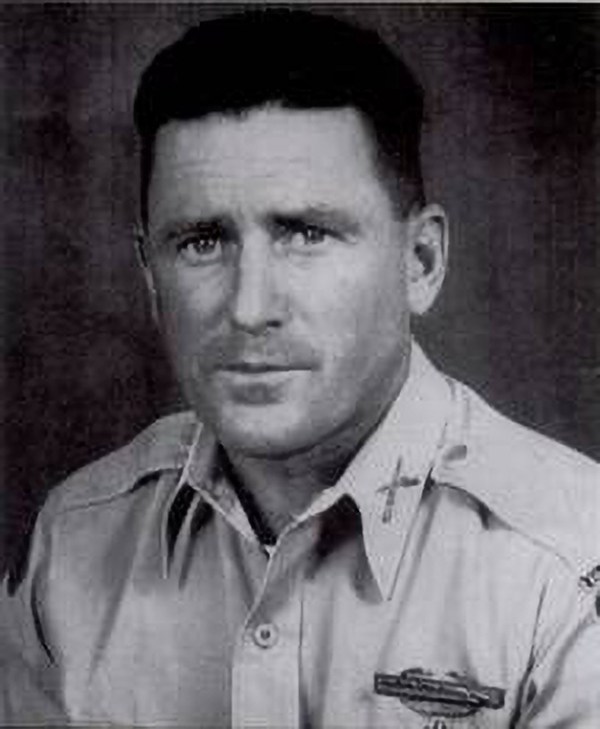

Sergeant First Class Stefan Mazak and Captain Albert Clement, pictured at right, the two other Special Forces members of Sully’s rescue team.

As part of Special Forces procedure, Sully was put in command even though he was of junior rank to Clement because of his previous time spent in the Congo. In some cases, enlisted men have become the unit commander over high ranking officers if they are more familiar with and have more knowledge of the particular Special Forces mission. All were fluent in French, the predominant language spoken in the Congo. Sully also spoke native Swahili and Lingala.

These men accomplished a mission that no one else in the world, including the United Nations, was able to do. By the time the United Nations brought troops in to restore order, Sully and his team had completed their rescue of 239 people from certain death.

Sully deFontaine, pictured in the photo at right, receiving the Legion of Merit from Colonel ‘Iron Mike’ Paulick.

Sergeant First Class Stefan Mazak

Captain Albert Clement

About the Authors:

Sully deFontaine

Born in Belgium to French parents and trained in 1943 by the British Special Operations Executive and Special Air Service (British SAS), Sully has been awarded over 20 U.S. and International decorations and has recently been inducted into the Special Forces Hall of Fame. Sully is a retired U.S. Army colonel and lives with his wife in the southwest United States.

In March of 2018, Sully deFontaine was presented the United States Congressional Gold Medal in front of the leaders of the United States Congress. Sully earned this out of respect for his achievements and service as a 17-year-old Frenchman in service to the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the predecessor to the Central Intelligence Agency.

In February of 2018 the Las Vegas Nevada Special Forces Association Chapter 51 was named the Las Vegas Nevada Sully H. deFontaine Special Forces Association Chapter 51. Sully deFontaine passed away on April 22, 2019. He was laid to rest with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery on October 19, 2019

Jack Lawson

Jack Lawson served in the United States Air Force as a missile electronics and nuclear weapons arming technician. He was later a member of a Foreign Legion counter insurgency unit during an anti-communist guerrilla war in Africa. Jack has authored two other books. He and his wife live in the southwest United States.

My name is SFC M. Scott Cameron, I knew Sully for many years. Through the years I heard many of his stories and exploits but for some reason I never heard this one. Over many lunches and dinners we would talk about many things other then the military. Sully had a way about him that you just knew that he was a man with many secrets and many adventures.

RIP my friend