SINGLAUB:

The Jedburgh Mission

Above, Lt. Singlaub hooked to the static line during Ft. Benning's jump training. (Singlaub Collection).

By Jim Morris

Originally published in the August 2020 Sentinel

Editors Note: Major General John K. Singlaub had his 99th birthday on July 10 of this year (2020). He is without doubt the most highly respected man in the Special Operations community. What most people in the community know about him is that he commanded the MACV Studies and Observations Group during the Vietnam War. But that is only an episode in his storied life, and not the most significant episode at that.

Outside Spec Ops he is best known for having publicly stated that President Carter’s plan to pull American troops out of Korea would lead to a second Korean War. Carter fired him, but did not pull the troops out, and we can speculate that thousands of American and Korean lives were saved by that.

What he should be famous for, in the Spec Ops community, is that after the debacle at Desert One, when Delta failed to extract our Iran hostages, he seized the opportunity to sell the Reagan administration on a plan he had nurtured and shaped for years. Today that plan has been realized and is known as the United States Special Operations Command.

This story originally appeared in Soldier of Fortune in 1981. It is the story of his first mission as a first lieutenant and captain in the OSS. Anybody who has run a mission like this will know it is a mission to die for. And he didn’t. Lucky him. Lucky us.

John K. Singlaub wanted to go to West Point real bad. He probably would have, he was told, except that his father was a Democrat. So he ended up as an ROTC cadet at UCLA. He was commissioned and started jump school at Fort Benning, GA, a week after his graduation in 1942. Gung ho to go to war in Europe or the Pacific, his first duty assignment was another frustration to test his resolve to be a career soldier. Second Lieutenant Singlaub was ordered to report all the way to the other end of Ft. Benning, clear over in Alabama. He served as a regimental demolitions officer and platoon leader in a parachute training regiment.

Making the most of his situation, Singlaub quickly demonstrated superior leadership skills under extreme difficulty by organizing successful small commando-type units to act as aggressors on FTXs. This, combined with good marks at UCLA in French and Japanese language studies, soon led to an invitation for Singlaub to volunteer for an unspecified “hazardous mission behind enemy lines.“ Anxious that he not spend the duration stateside teaching others to go to war, he immediately accepted.

In October 1943, Singlaub received orders to report to Washington. After checking in, he was sent to Building Q in the Foggy Bottom complex where the Office of Strategic Services was headquartered. He underwent initial screening and was dispatched later that afternoon to the Congressional Country Club in suburban Maryland, where a rather bizarre battery of psychological testing began. This included close live-fire tests and having explosive charges set off unexpectedly nearby.

Passing those tests, Singlaub recalls, “is a matter of being able to concentrate your mind on the physical things you have to do rather than worrying about whether you were going to get killed.”

Taking a sip of coffee as I interviewed Singlaub in his mountaintop home overlooking the small town of Tabernash, Colorado, I agreed wholeheartedly with that assessment. I once defined soldiering as being able to perform simple mechanical tasks while scared shitless.

Singlaub and others were selected for continued training. Many were sent back to regular military assignments or civilian jobs. The selectees were trucked to a nearby secret compound designated as “B-1,” now the location of the presidential retreat known as Camp David. The OSS training increased in difficulty and intensity, focusing very much on each individual.

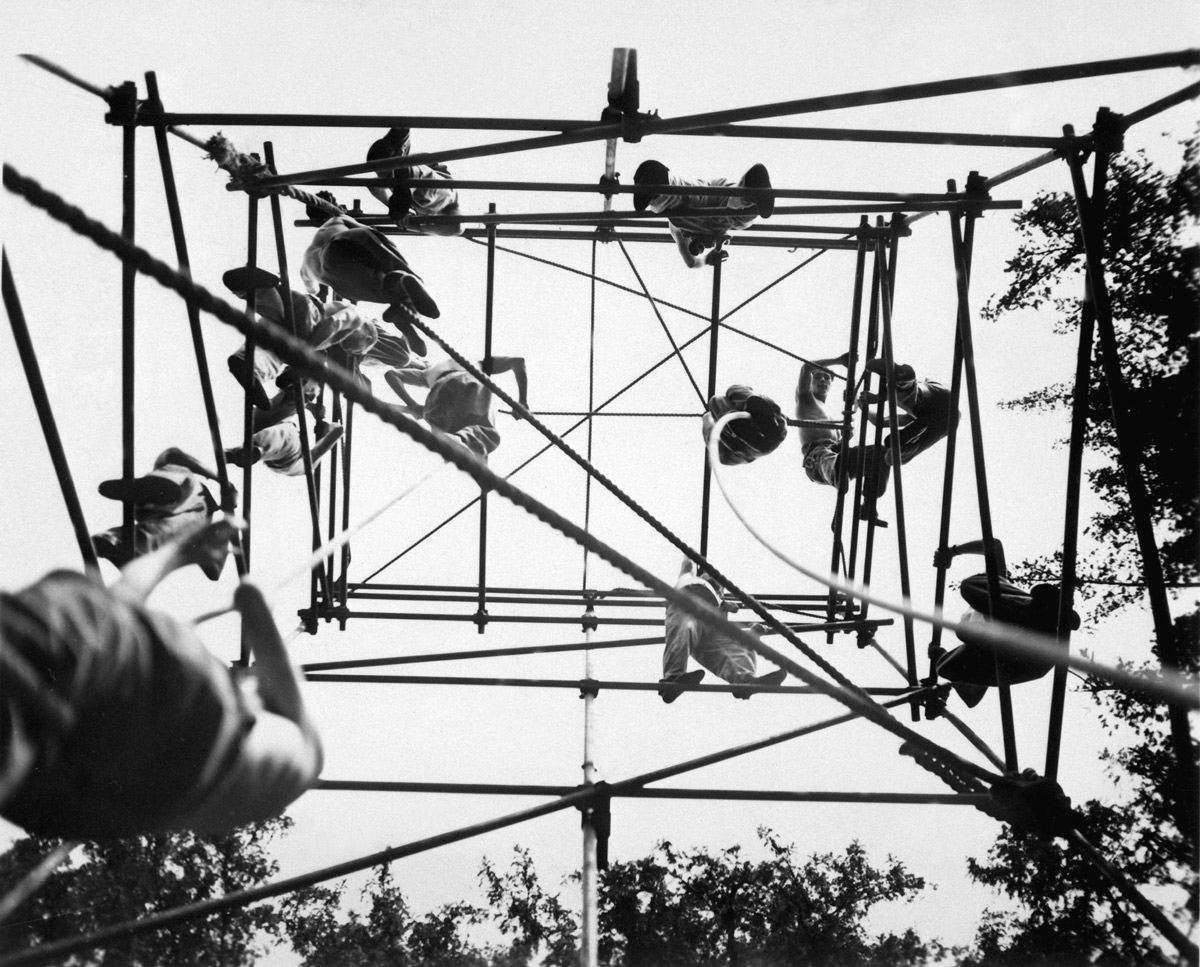

Jedburghs on high bars in obstacle course in Milton Hall, England. NARA FILE #: 226-FPL-MH-23 WAR & CONFLICT BOOK #: 737. ID: HD-SN-99-02396

Trainees like Singlaub who survived B-1 would be sent to Scotland for even more rigorous instruction before being assigned to what was known as a Jedburgh Team, a code name assigned by British Intelligence, taken from the name of a town in Scotland. Jedburgh Teams of three men each — two Allied officers and an enlisted radio operator were inserted behind German lines in Europe to help organize anti-Nazi resistance and carry out sabotage and intelligence-gathering operations. They were one of the forerunners of Special Forces A Teams.

A month after the Normandy invasion, Singlaub’s Jedburgh Team parachuted deep into German-occupied France to prepare partisan support for a southern invasion.

“The invasion of the north had already started, and my first mission was to train the maquisards, and prevent movement of German troops from the southern part of France up toward the invasion beachheads. So, I just cut all the railroads.”

“Blow the bridges?” I asked Singlaub.

He smiled and shook his head. “No, I blew about a foot off of every curved rail in the whole province. Every place there was a curve in the province, or where they had stacks of curved rails, I just chopped a foot off.”

“Took it out of the middle?”

“No, just took it off the end. They just didn’t move. There was no way that they could…”

“Did you interdict truck transport as well?”

“We did, with ambushes on selected roads. We had several Routes Nationale that went through our province. The Das Reich Panzer Division had tried to move through our area, and they were attacked by some of the maquisards before I got there. In retaliation — the Das Reich was an SS division —they moved into the town of Tulle in Correze and lined up all the young men. They numbered ‘em off, made ‘em count off one-two-three and so on. ‘Okay, all number ones are going to be released, number twos are going to labor camps, and number threes are going to be hung, right there.’ And so they started hanging these guys by putting a noose around their necks and pulling them up on balconies.

“Well, there were about a hundred-and-some in each of the three categories, so there were about a 110 who were going to be hung. But I guess the priest who was administering the last rites had some sympathy. So when they had hung 98 or something like that, he said, ‘Well, that’s all.’ ”

The Germans apparently had lost count, Singlaub said. “Part way through this they switched. The ones who were to go free were rejoicing, and the Germans said, ‘Okay, take the number ones and start hanging ones instead of threes.’ The whole thing was a terrible atrocity.” Singlaub said the German brutality continued. “They moved into the province to the north and decided they were going to wipe out a town called Oridor-sur-Glen. They went into the town, rounded up all the women and children and put them in the church, and put all the men in a garage. They stopped a streetcar coming out of Limoges, and everybody that had tickets for that town, they took off the streetcar and put in with the others, machine gunned the men in the garage, set the church on fire, and leveled the town.

“Someone from the garage managed to get out. He was left for dead and then came up from underneath this pile of dead and got out, and gave us these details.

“But despite these atrocities, we had more French maquisards wanting to join our unit than we could handle. They were not deterred. They were just fantastically brave, even though they lacked a lot of the skills that we would have liked them to have. And that was the job.”

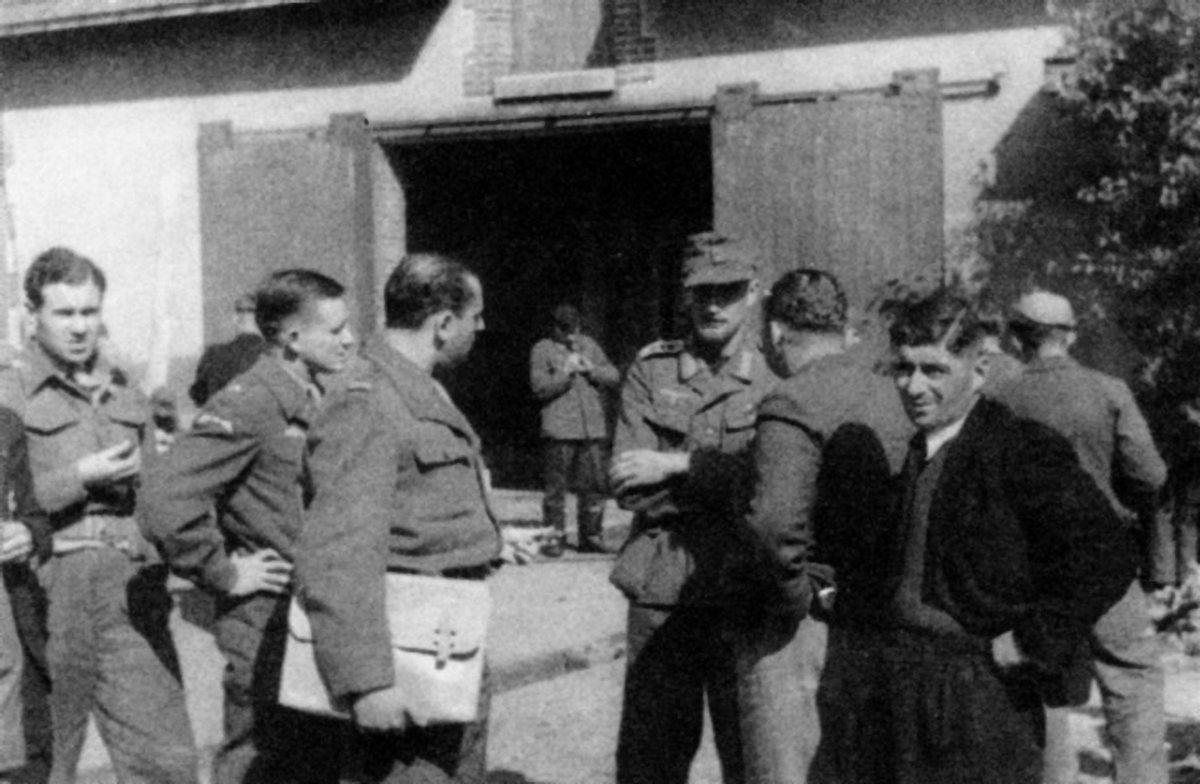

Singlaub (left) and other OSS team members question a captured German, with folded arms. (Singlaub Collection)

I nodded. “Let me ask you, sir, what was your life like on that mission? Where did you live; how did you move around?”

“Well, we parachuted in to a British agent living as a Frenchman. He was a captain in the British Intelligence forces, but was living undercover. He had indicated to London that there was a good potential for resistance in this area, and that he would run the reception committee. He gathered us up and took us to a little farmhouse and introduced us to leaders of this resistance movement.

“Two distinct groups had been brought together. One was a group headed by a regular army captain, in what was called the Armee Secrete (AS). The other leader had been a corporal in the French army, and he was a communist. This was the FTP, the Franc Tireur de Partisan.

“In my province I had a little better cooperation, although it was not complete. The communists would constantly try to steal any equipment drop that was coming into an area. If they found out that I was running an equipment drop for the AS battalion, they would go out and set up a reception committee, lay out the lights, and send signals, in hope that the airplanes would drop, and on at least one occasion they did.

“I complained that the aircraft didn’t come as I’d been told, and London came back with, ‘You must be out of your mind. The pilot claims he dropped the supplies.’ I found out later they had stolen the supplies. The communists were more interested in arming for the war after the war than they were in fighting the Germans in that area.

“With this group of the AS we were not only able to train them, we actually got permission to take the whole battalion on operations with trucks we had captured from the Germans, and trucks that had been made available for farm usage. These were civilians led by a few regular army people, and they had some NCOs who had seen military service.

“They were not just limited to my province. Because that was a rugged area, underpopulated by French standards, many people who had gotten into trouble elsewhere, moved into that area to live with the maquisards.

“We lived in a farmhouse, a very rugged old thing, with no indoor plumbing, of course. We didn’t live with the farmer. They gave us what was, in essence, a barn. That’s where we stayed a majority of the time, when we weren’t out doing the training and the initial reconnaissance.”

“You were a captain by this time?”

“No, I was a first lieutenant, and my Frenchman was a first lieutenant.”

“So that was kind of a lucky break for you in terms of career development, to be essentially a battalion commander when you were a first lieutenant.”

“Yeah, that’s right. Although I was really the adviser.”

I nodded. “I can’t imagine the Germans were not looking for you. Did you have any close calls while you were there?”

“Not during that time. Later on we did.

OSS control officer (left) briefs Singlaub and two other Jedburgh Team members prior to the three being dropped behind Nazi lines in occupied France. (Singlaub Collection)

“Later we got permission to attack four German garrisons that were in our area. And we eventually captured two of them. One was liberated (by the Germans), and one we had under siege, in the town of Egleton. These were garrisons of several hundred troops, a couple of companies.”

“And you would attack with an entire battalion?” I asked.

“Right. We put the town under seige. In two of them the Germans surrendered. We said, ‘you know, this is how many we have around and you’re completely cut off.’ We cut their telephones — they didn’t have radios — and cut their water. They surrendered. It was a great problem what to do with them. Some of the French, who had lost family to the SS battalion, wanted to just execute them. But I insisted, and we moved them out away from the main route, into the country, and kept them until after the war.

“But in the case of this town of Egleton, they had a radio, and I think they had some SS with them in there. I couldn’t crack it. When we moved against them they were holed up in a reinforced concrete school. We used mortars and British anti-tank rockets

“I called for an air attack on this school, after we’d shot out the top, using mortars, and these projectiles, which were anti-tank things. But they were still in there, defying us, so I radioed London and said that we wanted an air strike. One of the reasons I wanted an air strike was that the garrison we had under attack had called for air support, and they came in and strafed us, and dropped butterfly anti-personnel bombs.

“Well, this was pretty terrifying to these untrained maquisards. It was a real problem, and I was afraid that if they kept this up I wasn’t going to be able to keep control.

“So I told London we’d had many attacks. One of them was from a Heinkel He-111, twin-engine plane that came in very low. We could see the rivets on the thing. My Frenchman and I each organized two Bren guns and opened up when it came over us. We sensed that we could either see or hear the rounds hitting it. We knew that we had hit it. But it went off and disappeared.

“We found out later that we had actually hit it, and killed some of the crew, and the thing had crashed before it got back to its base.

“That made them mad, and we had a hell of a lot of air strikes against us. When I reported this to London, and requested that they hit that school, they said, ‘Well, according to you, you’re getting more air strikes from the Germans than the entire Third Army.’

“That was because all the aircraft were moving back from the beaches, and were in fact moving back toward Germany.

“One day we heard, but did not see, an aircraft fly very high over the area. Later I learned that it was an Allied reconnaissance flight for this special (British) Mosquito squadron they had, that did precision bombing.

“That night the anti-maquisard German force was coming up from Clermont-Ferrond, and they broke through, liberated a group in Ussel, and were on their way to this town of Egleton. So, well after dark, I gave the word to break contact and head for the hills. We had a prearranged rendezvous.”

That’s when the French presented him with a bill for all that food and wine.

“We’d been up for three days straight, so we were really bushed. My Frenchman, radio operator and I headed up, and I think that I must have been sleeping while walking, because I just didn’t remember it.

“I do remember getting to a farmhouse. We didn’t go into the farmhouse, we went into the barn, and just burrowed into the hay and went to sleep.

“Well, my radio operator had slept, and he woke up when a German troop came up and banged on the farmhouse and went in and searched the place, looking for maquisards.

Jedburgh's jump from a B-24.

“Of course, he couldn’t sleep. He was terrified, but my Frenchman and I were out cold. The next morning we got up and started toward the rendezvous. Up on some high ground we could see back toward the town of Egleton. We went to an open area, and saw four Mosquitos coming right on the deck. They flew directly to the town, went up into the air, came down, and four of them put their bombs exactly into that school. Absolutely leveled it.

“The trouble is the Germans had already gotten there, and moved on to find out what had happened to the garrisons in these other towns. The only people left at that time were some wounded Germans, and some people taking care of them. Probably less than a platoon had been left behind.

“By this time, after we had gotten permission to attack, and after Paris had fallen to the Allies, the Germans were interested in heading back to Germany. Our orders were to prevent them from getting from the Atlantic coast ports back to Germany by moving through our province. Our province was rugged enough so that we could pretty well stop them. Their main route was to the north, just south of the Loire River. We got permission to move the battalion up and attack Germans moving through that area.

“By this time we were able to move into towns. Generally speaking, when we’d go into a town, I’d take over the Gestapo headquarters, because I’d found that they were usually pretty well stocked, and in pretty good buildings. So they jokingly referred to me as the ‘American Gestapo.’

“We were royally treated compared to the austere eating conditions that we had in England. In England you could only get one egg a week. Well, we were out in farm country, so we could have eggs every day if we wanted. We could have meat. If there was any food available, we were given highest priority in the whole province.

“Later, when we moved into towns, or when we moved into better accommodations, our hosts would crack open a wall that they had sealed up to hide their best wines or their best cognac from the Germans. And they would produce the most incredible wine, just to celebrate the occasion — the arrival of the Allies.

“Eventually we were given instructions to exfiltrate the area. We crossed the Loire River in the vicinity of Orleans. We eventually made contact with some patrols that were on the south side of the Loire River. We crossed on a ferry that had been put into operation — the bridges had all been taken out — and went on into Paris. This was in October of ‘44, something like that.”

Singlaub then began looking for another good mission. “My intelligence officer in the maquisard was an Austrian by birth. He’d spent most of his life in France, but he was fluent in German. He had contacts in Austria. And there were a lot of French that had escaped from the labor camps in Austria, and had gone to the mountains. It was his suggestion that we take our team up there and help set up a resistance in the Austrian Alps, among the French who had escaped. So, I put the proposal to London.”

Singlaub even presented the proposal in person, returning to Paris two days later to await formal approval.

“When we came back to Paris I thought they were going to approve this thing, but apparently the status of Austria was under debate, because of the three-power thing: British-Russian-U.S. interests in that area. So that mission never took place.”

Singlaub returned to England for further training while awaiting reassignment. In December 1944, he volunteered to go to the Far East. Many of the Jeds had already left to go there. First, though, he had some homefront duty to complete. He received 30 days of leave in the States on his way to the China-Burma-India theatre. He and his fiancee, Mary Osborne, were married 6 January 1945, just prior to his new assignment in eastern Asia. He met her before joining OSS and they announced their engagement just prior to his deployment to Europe.

Now World War II was quickly nearing its end. But plenty of adventure lay in store for Jack Singlaub. Among other things, he would be dropping supplies to U.S. operatives assisting a guerrilla movement in French Indochina headed by a man named Ho Chi Minh. He would parachute into what later became North Vietnam. And he would lead a small commando team which made a daring daylight drop onto Hainan Island to free Allied POWs being held by 10,000 of Japan’s Hokkaido Marines.

Once on the ground, with his radio destroyed in the jump, he had the unpleasant task of being the bearer of bad news for the Japanese CO. The United States had dropped the atom bomb, and surrender by Japan was imminent. After refusing to talk with the Japanese lieutenant sent out to take him and his men captive, Singlaub brazenly informed the stunned commander that the tiny commando unit was taking charge of all Allied prisoners and military installations on the island

But that’s another tale.

James-Morris-160px-x-240px

About the Author:

Jim Morris joined 1st SFGA in 1962 for a 30-month tour, which included two TDY trips to Vietnam. After a two year break, he went back on active duty for a PCS tour with 5th SFG (A), six months as the B Co S-5, and then was conscripted to serve as the Group’s Public Information Officer (PIO). While with B-52 Project Delta on an operation in the Ashau Valley, he suffered a serious wound while trying to pull a Delta trooper to safety, which resulted in being medically retired.

As a civilian war correspondent he covered various wars in Latin America, the Mideast, and again in Southeast Asia, eventually settling down to writing and editing, primarily but not exclusively about military affairs.

He is the author of many books, including the classic memoir War Story, now available in Ebook format in The Guerrilla Trilogy, which also includes his books Fighting Men and The Devil’s Secret Name . The Dreaming Circus was released in the summer of 2022 — information available at https://www.innertraditions.com/books/the-dreaming-circus.

Leave A Comment