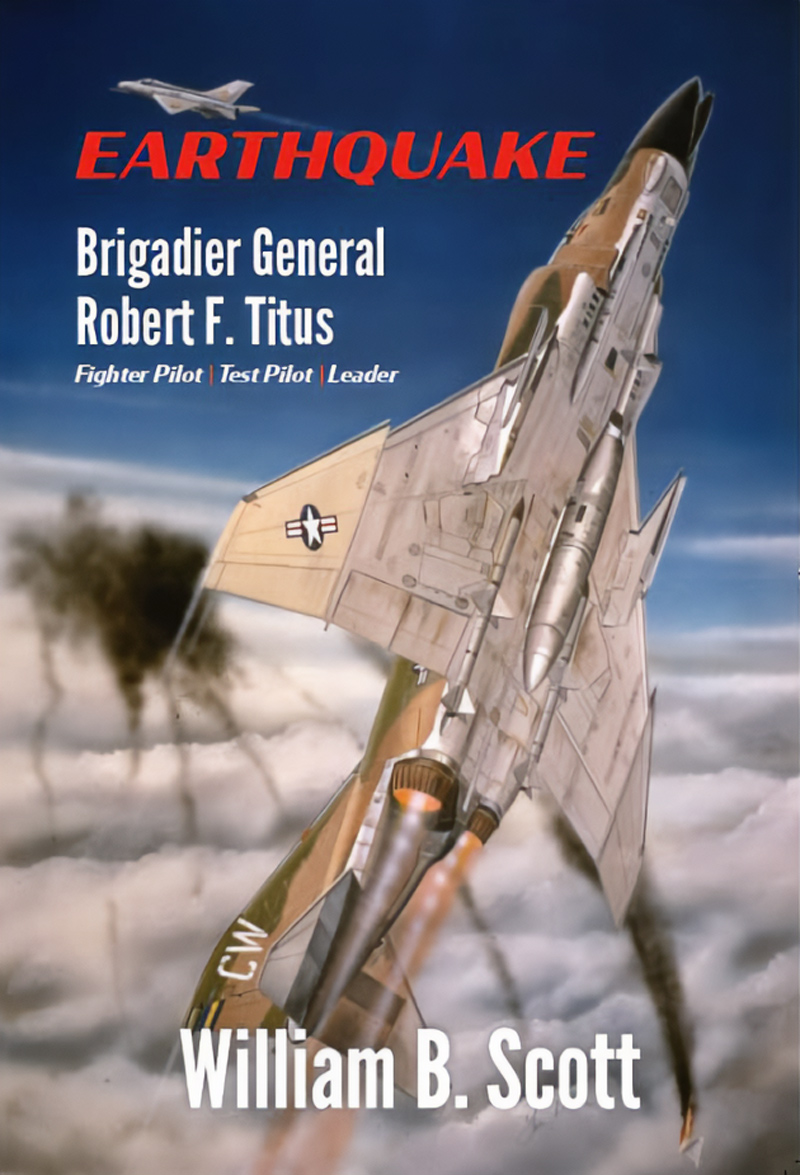

EARTHQUAKE

Brigadier General Robert F. Titus

Fighter Pilot | Test Pilot | Leader

By William B Scott

Special Forces and air-to-ground references excerpted from EARTHQUAKE: Brigadier General Robert F. Titus — Fighter Pilot | Test Pilot | Leader; North Slope Publications, March 24, 2024; VIETNAM—pages 75-77, 86, MG JOE ARBUCKLE ACCOUNT—pages 132-134, KOREA—pages 1-3 and 6-7; used with permission.

BG Robert F. ‘EARTHQUAKE’ Titus

6 Dec 1926 – 8 Sep 2024

Army Paratrooper—82nd Airborne

•

Korean War:

F-51 Fighter Pilot—101 Missions

•

Test Pilot—Century Series &

Zero Launch F-100

•

Nonstop Trans-Polar Flight—

F-100 Fighter

•

Germany:

Nuclear Alert – F-105 Fighter Pilot

•

Vietnam:

Cdr. Skoshi Tigers F-5C;

350 Combat Missions

•

Vietnam:

Cdr. 389th TFS —

Three MiG-21 Kills;

100 Combat Missions in F-4 Phantom

•

Program Officer – F-15 Eagle Fighter

Editor’s note: The brave pilots of both fixed and rotating wing aircraft that were so critical to Special Forces troops on the ground were amazing. Brigadier General Robert F. Titus was one who stood out among these men and went on to have a remarkable and impactful career, as noted in the book Earthquake (his nickname). The author shares this excerpt highlighting his close combat support.

VIETNAM

In April 1966, the 4503rd Tactical Fighter Squadron (Provisional) at Bien Hoa was officially disbanded and the former test unit renamed the 10th Fighter Commando Squadron—which Titus would command—under the 3rd Fighter Wing. Combat missions were all flown by American pilots, while Vietnamese pilots were being trained at Williams AFB.

When Titus left the States, he led a flight of seven F-5Cs to Bien Hoa, refueling in the air several times en route.

“I stayed there [from May 1966 to January 1967] and flew some 300 combat missions—bombing the jungle and targets of opportunity; whatever we had to do,” he said. A significant number of missions were tasked to provide close air support for ground troops.

One dicey mission rescued a MIKE FORCE team, a small unit surrounded by an enemy force. An American officer was calling for air-delivered ordnance or artillery to take out Viet Cong that were “danger close.” However, the area was blanketed with clouds. Titus knew the patrol would never survive without air support—and that was his unit’s primary mission. He carefully descended through the cloud deck, not knowing whether—as pilots wryly joke—“there were rocks in those clouds,” and told the Special Forces commander to call when he heard the aircraft overhead.

The officer did so, Titus pulled the fighter into a 90-270-degree turn to ensure he was on the exact flight path he’d just flown outbound, but going the opposite direction, and ordered the ground commander to “pop smoke.” “Earthquake” spotted the plume, adjusted his run-in track slightly, and dropped two cans of napalm precisely where the trapped soldier directed. The ensuing firestorm significantly dampened Viet Cong attackers’ enthusiasm, allowing the patrol to escape. The F-5C was exposed to small arms fire, but Titus landed at Bien Hoa unscathed.

10th Fighter Commando Squadron "Skoshi Tigers” F-5 Freedom Fighters at Bien Hoa. (Courtesy of the General Titus Family)

The Bien Hoa-based outfit was a detachment of Mobile Strike Force Command, a highly effective Army Special Forces component that routinely conducted quick-reaction raids, reconnaissance, intelligence-gathering, and search and destroy patrols. Comprising a few Green Beret lieutenants, non-commissioned officers and Nung fighters, MIKE FORCE units were named after Special Forces Lieutenant Colonel Miguel de la Pena, who had commanded the first group in 1964. Typically, Nungs—people of Chinese descent—were recruited locally. Many were former French Foreign Legion troops, but others were criminals who had been released specifically to fight the Viet Cong.

Titus accepted the invitation, joining USAF Captain Mark Berent, an F-100 fighter pilot based at Bien Hoa, who had “spent much time with the Special Forces III Corps MIKE FORCE, including going on patrol with them in the Loc Ninh area,” according to Berent’s author website.

Another historically significant Skoshi Tigers mission occurred on July 9, 1966, in support of a complex Army operation designed to lure a sizable Viet Cong force into a trap. Commander of the 1st Infantry Division (The Big Red One), Major General William E. DePuy, had tasked Colonel Sidney Berry to organize an ostensibly vulnerable convoy as bait. Berry “chose the Minh Thanh Road/Route 245, which branched off Highway 13, as the best site for the operation,” according to an official Army history.

Berry notified the local Vietnamese Province Chief of the convoy’s destination, suspecting one of the chief’s staff members was an enemy informant.

Designated Task Force Dragoon, the convoy moved out early in the morning, preceded by artillery and air strikes on suspected Viet Cong ambush positions. At 11:10 a.m., the Viet Cong attacked the string of vehicles—but were surprised to also encounter tanks and M113 armored personnel carriers. A vicious firefight erupted.

Zero Launch F-100 after rocket ignition. The Super Sabre also is in full afterburner. (Edwards AFB, California). Photo via William B. Scott

Titus and other Skoshi Tiger pilots joined F-100 Super Sabres and heavily armed gunships to provide blistering air support, dropping napalm and bombs, and making repeated strafing runs with 20-mm ammo. The battle was ferocious, both on the ground and in the air, requiring pilots to fly multiple sorties.

“I returned to [re-arm and] refuel,” Titus recalled, “and went back several times. It was an hours-long operation.”

The Viet Cong started withdrawing around 12:30 p.m. and attempted to organize a counterattack, which was quickly thwarted.

Twenty-five American soldiers were killed in what’s known as the Battle of Minh Thanh Road. The outgunned Viet Cong regiment suffered massive losses: “238 killed…and a further 300 were believed to have been killed, but the bodies were removed,” according to the Army’s historical account.

That mission earned Titus his third Distinguished Flying Cross, this time with a “Combat V” symbol.

The award citation provides more details than the recipient does:

“…to…Lieutenant Colonel Robert F. Titus…for heroism while participating in aerial flight as a pilot of the 10th Fighter Commando Squadron while participating in aerial flight near Route 13, Republic of Vietnam, on 9 July 1966. On that date, Colonel Titus demonstrated outstanding airmanship and courage in the highly successful accomplishment of a close air support mission under extremely hazardous conditions, including continuous exposure to intensive, hostile ground fire. Colonel Titus executed multiple bombing and strafing attacks on a Viet Cong force which had ambushed a friendly forces convoy. The close air support he provided disrupted the hostile offensive and denied the opportunity for pressing effective attacks on friendly personnel and equipment. The outstanding heroism and selfless devotion to duty displayed by Colonel Titus reflect great credit upon himself and the United States Air Force.”

Characteristically, he dismisses the honor. “I’ve never been much on decorations,” he said. “Sometimes, they ignore [more deserving actions] where you had a hairy experience.” He noted that the value of such decorations was diminished by pilots receiving as many as three Silver Stars and numerous Air Medals for leading combat missions over North Vietnam’s “Route Pack VI”. Titus and other USAF, Navy and Marine Corps pilots flew—and often led—countless missions in that sector, but never received a medal.

The Marine Corps had just the opposite mentality, rarely handing out decorations for even unbelievably valiant combat accomplishments. Titus also made a point of saluting helicopter air crews for flying some of the most dangerous missions of the war—especially search and rescue efforts to retrieve downed pilots and ground forces in dire straits.

Dogfights: “F-4 Phantoms Duel over Vietnam” (S2, E5) | Full Episode. At 16:50 in the video, on May 22, 1967 then-LTC Robert Titus leads a flight of newly gun-quipped F-4 Phantoms on an escort mission over North Vietnam when two MiG-21s attack.

POST-VIETNAM HEADQUARTERS ASSIGNMENT

During a post-Vietnam headquarters assignment, Titus fought long and hard to ensure the USAF’s next-generation F-15 Eagle fighter would be equipped with an internal 20-mm cannon. To underscore how critical a gun-equipped fighter is, when supporting ground troops, the book includes this account by US Army Maj. Gen. Joe Arbuckle (Ret.):

Although not available to [Titus] in 1973, an example of a gun-armed fighter having a major positive impact was related by retired Army Major General Joe Arbuckle, an advisor with a South Vietnamese unit, charged with calling in air strikes:

“On 30 Mar 72, the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) launched the largest offensive of the entire Vietnam War. Over 120,000 NVA troops assaulted across the border into South Vietnam on three major axes. They came with tanks, heavy artillery, anti-aircraft weapons, etc., and the assault lasted until Oct 72. The NVA was aided by the local Viet Cong in coordinated attacks against us.

“At that time, the only combat troops left on the ground were us [American] advisors. I was then detachment commander for Advisory Team 22, and we only had 55 advisors on the entire team spread across II Corps from Qui Nhon on the coast to Pleiuku, Kontum, Tan Cahn, etc. near the Ho Chi Minh trail. We were soon operating with two- and three-man advisory teams attached to South Vietnamese units.

“The NVA hit our Corps with at least three divisions totaling over 50,000 troops. The ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam) were surprised and overwhelmed; many of them dropped their weapons and ran. We were always concerned about the ARVN running and leaving us behind. Within the first three weeks of the assault, we lost nearly half of our team, mostly WIA’s (wounded in action), but some KIAs (killed in action), and three-fourths of the Corps territory.

“I immediately relinquished command and was sent to where the action was happening, to include…time on the ground at fire bases English, Crystal, Two Bits, etc., in Binh Dinh province, and finally to Phu Cat District. I directed hundreds of air strikes.… It was a wild time and we advisors were in remote areas fighting and existing with the ARVN. A PRC-25 radio was our lifeline for air support and evacuation. It is estimated our combined…efforts killed or wounded 20-40,000 NVA troops in II Corps, mostly due to airstrikes, during this period.

“Our advisor motto: ‘First in, last out.’”

Lance Corporal Johnny Jones, an AN/PRC-25 radio operator for D Battery, 12th Marines, relays the message for artillery coordinates. (US Marine Corps photo)

Arbuckle vividly recalled one particular battle near Fire Base English. During the Easter Offensive outlined above, then-1st Lieutenant Arbuckle and another American advisor were flown to a hilltop overlooking a stream and large farm building surrounded by trees.

“We knew the enemy was in those trees,” he said. “I contacted a FAC (Forward Air Controller), who called in several F-4s. I directed airstrikes on enemy positions…but each time the F-4s pulled up, after dropping their bombs, a .51-caliber anti-aircraft gun would start shooting at them. I couldn’t spot that [enemy] gun.”

The F-4s called “Winchester”—no remaining ordnance—and announced they were departing.

“I told the FAC to have the F-4s make a gun run on the farmhouse. The FAC came back, ‘No cannons on F-4s!’ I couldn’t believe it!

Fortuitously, a Navy or Marine Vought A-7 Corsair checked in with the FAC. Arbuckle directed the pilot where to drop several bombs, while searching with binoculars for that deadly .51-caliber AA gun.

“I finally spotted it next to the building in the middle of a dry rice paddy,” he said. “But it was in a covered ‘spider hole’. The cover would be moved, and the gun would fire at the [fighters] when they pulled up. Then the cover would drop back down. I saw the muzzle flashes; that gave them away.”

The A-7 had expended all of its bombs but had a 20-mm cannon. Arbuckle directed the pilot to strafe the hidden gun site, but his rounds missed on the first run. A quick correction call and the A-7’s second gun pass “stitched right across the spider hole. No response from the gun after that.”

An ARVN interpreter later told Arbuckle that the .51-caliber gun was in place to protect the building, which housed an NVA headquarters consisting of 20-40 people.

“That’s an example where a cannon made a believer of me!” Arbuckle asserted.

For his professional, highly effective direction of air assets to eliminate a major NVA facility, Arbuckle was awarded the Vietnam Cross of Gallantry with Silver Star, one of two he received.

Awarding then-1st Lt. Joe Arbuckle (tall officer at far left) the Vietnam Cross of Gallantry with Silver Star. (Courtesy of the General Titus Family)

KOREA

Earlier, during the Korean War, Titus flew F-51 “Mustangs” and F-86 “Sabres”. Most F-51 missions were air-to-ground, and the Mustang’s oil cooler was vulnerable to small-arms fire.

- Early 1952

- K-46 — Hoengsong Airfield

- South Korea

It was to be another routine combat sortie north of the Demilitarized Zone that divided Korea, searching for railroads, trains and trucks hauling materiel to enemy troops at the Front. The mission: interdict whatever was moving ammunition, guns, food, etc. to Chinese and North Korean troops. That meant bombing and strafing targets designated by mission planners, as well as targets-of-opportunity.

The force of U.S. Air Force hunters consisted of three North American Aviation F-51 Mustang fighters carrying one 500-pound bomb under each wing and a full load of linked .50-caliber ammunition. Armed with six .50-caliber Browning machine guns, the single-engine, long-range Mustang was one of America’s primary fighter aircraft rushed to Korea, immediately after the North invaded. Later, when jet-powered North American F-86 Sabres arrived, the F-51 reverted to a full-time fighter-bomber role.

First Lieutenant Robert F. Titus had flown numerous combat missions in Korea, and always brought his fighter back to K-46, a 3,000-foot gravel and dirt airstrip carved from a riverbed. His aircraft had collected a few holes from anti-aircraft and small-arms fire on previous missions, but nothing serious.

That run of good luck was about to end.

After bombing and strafing enemy transports and rail lines in North Korea, the three-ship flight was southbound, returning to base. Titus noted his fighter’s engine temperature was climbing rapidly. The Mustang’s cooling system had taken small-arms hits and fluid was streaming behind the aircraft. It was only a matter of time, before the big piston-driven Allison engine would overheat and seize up.

“My feet were getting hot” and the altimeter was unwinding smartly. Not waiting for the 12-cylinder powerplant and massive four-blade propellor to suddenly freeze, Titus jettisoned the canopy, stood on the seat and “went over the side,” he recalls. The horizontal stabilizer whacked the inside of one ankle, “but it didn’t break anything. It was a minor wound and I didn’t bother with it.

First Lieutenant Titus and his F-51 Mustang “No Sweat” in South Korea. [K-46 — Hoengsong Airfield,1952]. (Courtesy of the General Titus Family)

“What was interesting, nobody saw me [bail out]. There were only three of us [in the flight]. The other two guys saw the airplane crash, but didn’t see me get out.”

The pilot immediately pulled his ripcord and checked the parachute canopy blossoming overhead. Then he hit the ground—hard. “I was much lower than I thought. I might have been as low as a hundred feet. Maybe higher, but it was pretty low.”

About any other pilot would have broken an ankle or leg, bailing out so close to terra firma. But Titus was no typical Air Force pilot. At the end of World War II, he’d been trained as a paratrooper and had made numerous jumps as a member of the U.S. Army’s elite 82nd Airborne Division. More about that later…

A quick self-assessment confirmed he had no major injuries. “My immediate concern was, ‘Where the Hell am I?’” he said. “I’m somewhat concerned, obviously, wondering what I’m going to do. First up: What are my resources, my assets?”

The downed pilot didn’t have long to wait for a bit of high-velocity direction. “I see these guys coming toward me, and they’re wearing quilted pajamas. So, I pull my pistol and go bang, bang and they go brrrrrrrt!”

Oh shit, this is not good. I’m gonna buy it now!

Titus’s standard-issue Colt 1911 .45-caliber semiautomatic was no match for Chinese troops armed with full-auto machine guns. He took off, firing on the run, and dived into a bomb crater. Peeking over the rim confirmed that enemy soldiers were closing on his position. As luck would have it, he’d parachuted into the Demilitarized Zone, a stretch of disputed territory near the 38th Parallel, which separated allied and enemy forces.

To avoid being shot or captured, “I figured I’d better hunker down.” But those enemy troops had spotted him and were approaching—fast.

“Then I hear an American voice: ‘Keep your head down and crawl this way.’ I was just north of some friendly positions—an area dotted with Marine [Corps] bunkers. They laid down suppressing fire,” driving away the bad guys, while Titus crawled to the bunker.

The grounded pilot was now miles from his air base, prompting a question: “What the Hell do I do now?” A Marine pointed to a road, “and next thing I knew, I was hitching a ride south on the MSR.” That Main Supply Road was the primary north-south link between troops on the front lines and rear-area supply depots. Trucks routinely traveled it, hauling rations, ammunition “and whatever the troops needed.

“Earthquake” Titus and the F-51 he flew on the final official USAF Mustang flight. (Courtesy of the General Titus Family)

They used to haul them right through our base,” Titus remembered. “We would trade things [with drivers], like whiskey for guns. We had whiskey, they had guns; we wanted guns.”

- Titus claims the numerous close air support and interdiction missions he flew in the Mustang were fairly routine. Obviously, one was considered exceptional, because it warranted a Distinguished Flying Cross, one of four he eventually earned in combat. On March 3, 1952, near Sohui-ri, he led a flight of three F-51s down through dense clouds to attack an enemy position. Ultimately, according to the DFC award citation, “Lieutenant Titus personally destroyed two heavy mortar positions, two bunkers and an ammunition dump.”

A low-level mission searching for targets-of-opportunity also hardly qualified as “routine.” The flight spotted several enemy bunkers dug into a ridge and immediately attacked. As pilot Bob Herman pulled off from a strafing run, he called, “There’s another one at the top.” Titus was hosing a target lower down, glanced up and saw muzzle flashes from the bunker above him. “I put my pipper on it and gave it a good burst [of .50-caliber rounds]. It really was a little late for that. I needed to yank it and get the Hell out of there. I thought I was going to hit the ridge but didn’t.” Postflight, a crew chief pulled a tree branch and leaves from the F-51’s oil-cooler inlet. Titus literally had flown through treetops along that ridge line.

In his twenties, the pilot had adopted a fatalistic attitude that would remain through a career fraught with such close calls. “I was never [concerned] after the fact,” he explained. “I’m on the ground. I’m walking. I’m not worried about what might have been.”

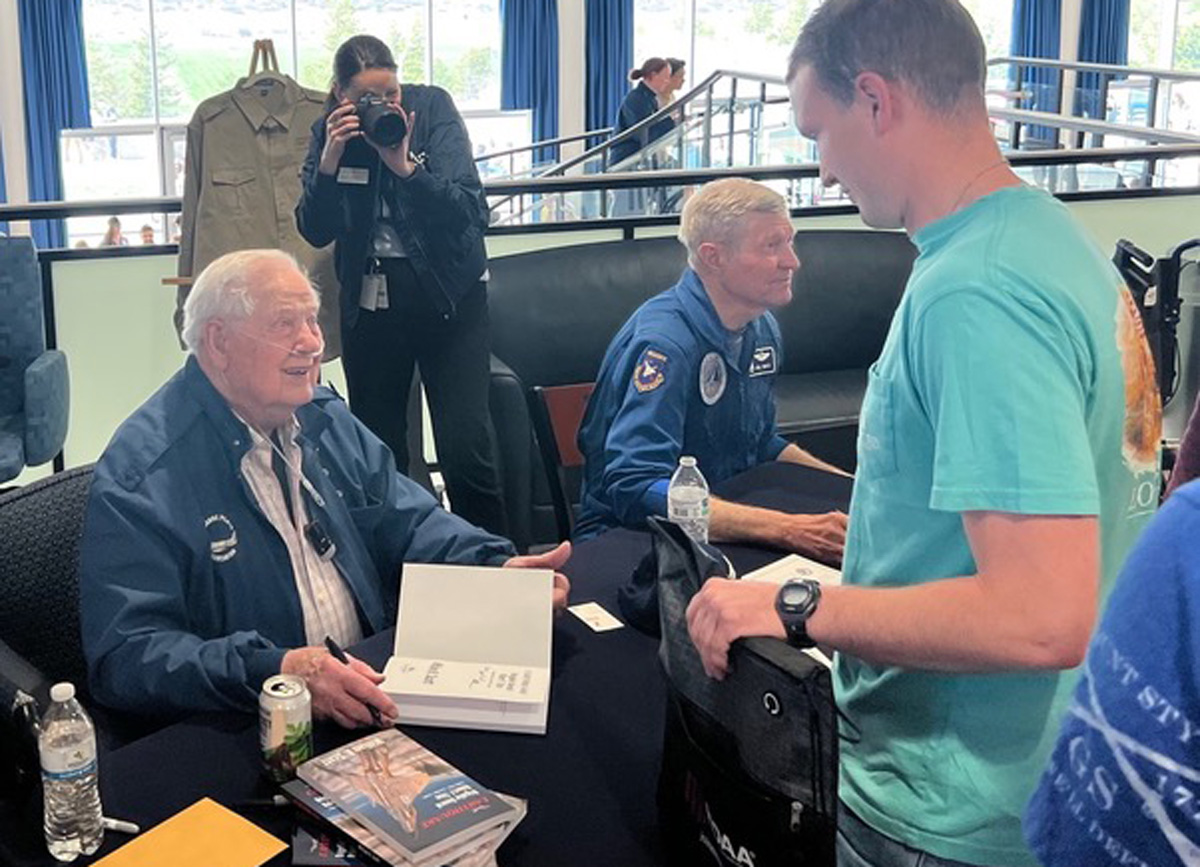

Brigadier General Robert F. Titus (USAF-Ret.) and “Earthquake” author Bill Scott signing books at the U.S. Air Force Academy, following an “Heritage Moment” event that honored Gen. Titus (25 April 2024). Each Class of 2024 AFA cadet received a copy of the book as he/she entered the Arnold Hall theater that day.

General Titus passed away a few months later on 8 Sept. 2024 and is interred at the USAF Academy cemetery. (Courtesy of the General Titus Family)

About the Author:

William B. (Bill) Scott is an author and consultant, following a 22-year career with Aviation Week & Space Technology, where he served as Rocky Mountain Bureau Chief and wrote more than 2,500 articles on aerospace, flight testing, and military operations. A graduate of the U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School and a licensed commercial pilot, he has logged 2,000 flight hours on 81 aircraft types and holds a B.S. in Electrical Engineering from California State University–Sacramento.

Bill has co-authored Inside the Stealth Bomber: The B-2 Story (nonfiction), Space Wars: The First Six Hours of World War III and its sequel Counterspace: The Next Hours of World War III. His solo-written novel The Permit, published in 2012, was inspired by the tragic death of his eldest son. He has written three nonfiction books, License to Kill: The Murder of Erik Scott (released in 2020), Combat Contrails: Vietnam (released in 2021), and his most recent book Earthquake: Brigadier General Robert F. Titus, Fighter Pilot | Test Pilot | Leader was released in March, 2024. More about his work can be found at www.williambscott.com.

During his nine years in the U.S. Air Force, Bill flew classified nuclear-sampling missions, worked at the NSA on satellite communications security, and served as a test engineer on fighter and transport aircraft programs. He later managed flight test programs for General Dynamics, Falcon Jet, and Tracor Flight Systems.

Bill and his wife, Linda, live in Colorado. They have two grown sons, Erik and Kevin. Tragically, Erik was killed in July 2010 in a senseless and horrific incident that profoundly changed their lives.

Leave A Comment