“Another died in my place.”

Part 1

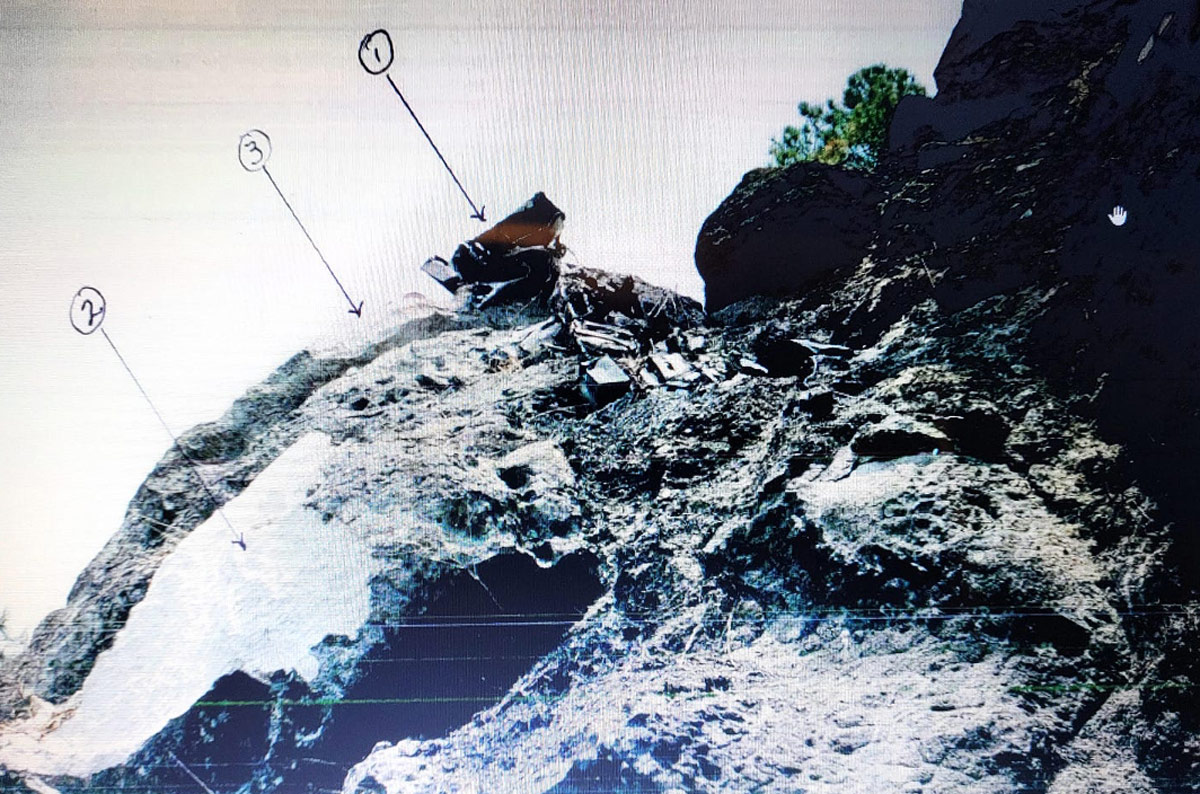

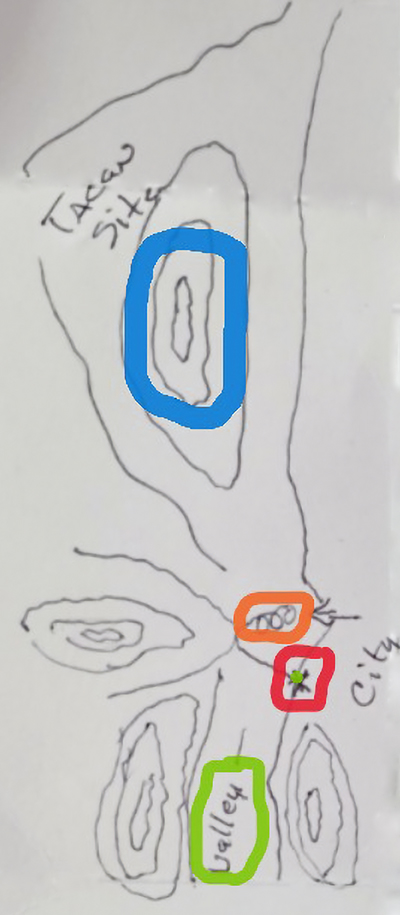

Located atop Cerro de Mole in Honduras, TACAN was a highly classified U.S. radar and communications intercept site. A single dirt road led from the town of La Paz up to the site whose elevation is 6,631 feet. (Credit: Google Earth)

By Greg Walker (U.S. Army Special Forces, Ret.)

“I will add this about Medevac crews past and present, when we receive a request for help, we will respond to the best of our capability, we will find a way to help if at all possible. Our mission requires risk-taking beyond most other aviation units. The 5 years I spent flying Dustoff was the most rewarding of my military career.” — Ken Kik, Flight Medic, 571st Medical Company (Air Ambulance)

“When in command—Command. Do not ever give in to the wrong course of action, despite pressure and opinions of others. Command is not a popularity contest. It is a responsibility. First, the mission was not a life-threatening mission and should not have been approved.

“Once the XO decided to launch a second attempt, although the wrong decision due to weather conditions, he now went down the slippery slope of high risk by pushing the pilot to fly the mission. Pressuring the pilot in command was yet again unprofessional and poor leadership. Once he was aware the co-pilot was not NVG qualified, another qualified crew should have been used if he persisted to order the mission.

“Again, it still would have been wrong to launch. By approving a non-qualified crew, the XO made a fatal decision which was also a violation of regulations. Never let enthusiasm overcome capabilities. Never.

“The XO’s actions resulted in the death of those brave Americans who never, ever, should have launched. He should have been severely punished and not only relieved.” — Major General (Ret.) Kenneth R. Bowra, https://gsof.org/kenneth-bowra-bio/

Prologue

On May 13, 1991, a California National Guard MEDEVAC crew was tasked to provide then nighttime air evacuation of a non-emergency Army soldier from a mountain top radar site in Honduras. Aborting the first attempt due to poor weather, the crew was released for the night, and a ground evacuation was arranged. Against Army aviation regulations and the MEDEVAC SOP for the 4/228th Aviation Battalion to which the CAL Guard crews were attached the executive officer for the 4/228th pushed for a second attempt. It resulted in the deaths of the three female crew members and the severe injury to the crew chief, the only survivor of the accident. This is their story.

As Operation Desert Shield began (August 2, 1990–January 17, 1991), both Army Reserve and National Guard MEDEVAC units began being called up for duty with both CONUS and OCONUS taskings. On November 21, 1990, the 126th Air Ambulance Company, California National Guard, was sent to Fort Bliss, Texas. Its mission was to assume the duties of the 507th Medical Company (Air Ambulance) as the 507th (AA) was being deployed for Operation Desert Shield and what became Operation Desert Storm.

“The first MEDEVAC unit to deploy to the Persian Gulf region was Delta Company, 326th Medical Battalion, 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault). Maj. Scott Heintz, who had taken over just one month prior, was the commander. He and the first three aircraft and crews arrived on 20 August and immediately assumed MEDEVAC alert.

“When the 326th received its deployment orders, it had one Forward Surgical MEDEVAC Team (FSMT) of three aircraft on temporary duty with the Joint Task Force Bravo in Honduras. Heintz received permission to recall those aircraft. With operations still ongoing in Central America, the 571st Med Det (RA) at Fort Carson, Colorado, was directed to self-deploy three UH-1Vs to Honduras.

“As active-duty units deployed into the theater, both USAR and ARNG units were rapidly activated to fill in at Army garrisons in the United States and Europe. The 126th Med Co (AA), California ARNG, was activated and sent to Fort Bliss, Texas, and Fort Sam Houston, Texas, assuming the home missions of the 507th. It also deployed three aircraft to Soto Cano Air Base in Honduras. On that deployment, a 126th crew was lost while flying a night rescue mission on 13 May 1991, and Capt. Sashai Dawn, 1st Lt. Vicki Boyd, and S.Sgt. Linda Simonds were killed. The crew chief survived and was recovered by rescue forces the next morning.

“When the 326th received its deployment orders, it had one Forward Surgical MEDEVAC Team (FSMT) of three aircraft on temporary duty with the Joint Task Force Bravo in Honduras. Heintz received permission to recall those aircraft. With operations still ongoing in Central America, the 571st Med Det (RA) at Fort Carson, Colorado, was directed to self-deploy three UH-1Vs to Honduras. 1st Lt. The 571st deployment took five days, with stops in San Antonio and Brownsville, Texas; Vera Cruz, Mexico; Belize City, Belize; and then into Soto Cano Air Base in Honduras. The crews flew at 90 knots and logged twenty-six flight hours in route. At Soto Cano, they assumed MEDEVAC duties for the next three months until replaced by another group of 571st pilots and then eventually crews from the 54th Med Det (RA) from Fort Lewis, Washington, and the 126th Med Co (AA) from the California ARNG.” — Call Sign “DUSTOFF”: A History of U.S. Army Aeromedical Evacuation from Conception to Hurricane Katrina, by Darrel D. Whitcomb, https://medcoe.army.mil/borden-tb-dustoff

However, the MEDEVAC crews coming from the Reserves and National Guard to support missions in Southwest Asia and Honduras faced significant obstacles. One active-duty aviation officer assigned as an advisor to the 347th Med Det (RA), USAR, from Miami, Florida, deployed then to Saudi Arabia in December.

“Capt. Randy Schwallie, an active-duty officer previously assigned to the Flatiron Detachment at Fort Rucker, Alabama. As DESERT SHIELD began, he saw a message stating that the 347th needed an active-duty advisor for their upcoming deployment, and he volunteered. He reported ASAP to Fort Stewart to ship out with the “Dolphin Dustoff,” as they were known. Upon the unit’s arrival in Saudi Arabia Schwallie began encountering and resolving as best he could the challenges Reserve and National Guard MEDEVAC units were facing—these were similar in nature to what the 126th crews at Soto Cano encountered upon their arrival.

“I am becoming increasingly aware of the lack of aviation support that we are receiving through our chain of command,” he wrote in his personal log. “We have not been able to get good weather reports, tactical locations of the refueling points, or information about the aviation intermediate maintenance unit that supports us. I am starting to understand the saying that “medical aviation is a stepchild that no one wants to own…We serve two masters; the medical and aviation communities, but we don’t seem to serve either one very well.” Using personal connections within the aviation community, Schwallie was able to get his troops some briefings on aviation operations, airspace control, and the enemy forces arrayed to the north of them. He was not getting any of that data through the medical chain.” — Call Sign “DUSTOFF

MEDEVAC support for the U.S. clandestine war in Honduras

At Soto Cano, CPT Sashai Dawn was experiencing the same shortcomings. Upon the crews’ arrival Dawn, per the crash report, met with the 4/228th’s battalion commander. He stated in his interview, conducted on May 17th and while he was on mid-tour leave, he was “pleased with the experience level of the incoming unit”. Further, he noted the pilots averaged 1500 hours of flight time and were on average 35 years of age. It was noted in his interview the last rotational MEDEVAC unit’s “high time” aviator possessed only seven hundred hours in the air. The battalion commander himself possessed 18 years of military service with 3400 hours of flight time.

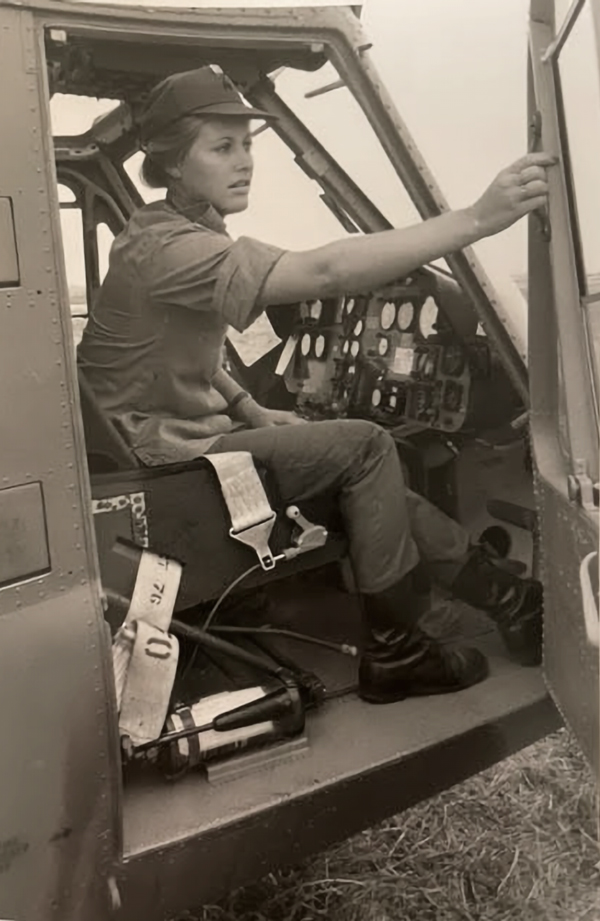

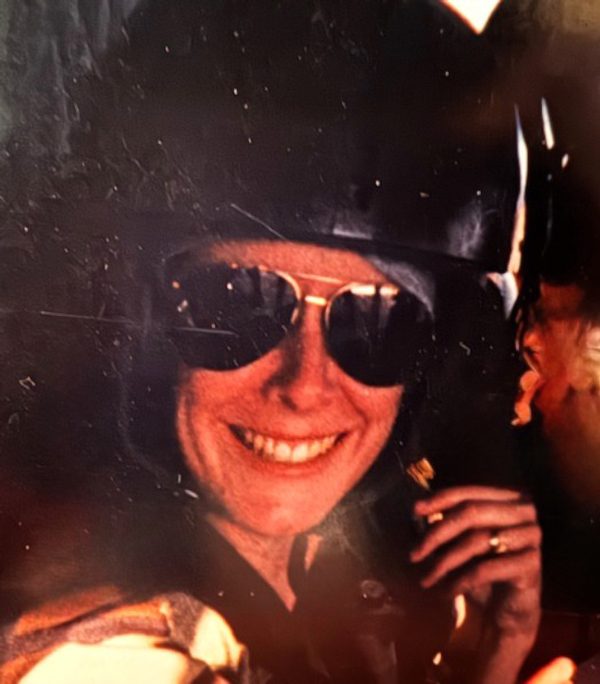

CPT (P) Sashai Dawn had over 1500 hours of flight time as a MEDEVAC pilot and was being considered to take command of her CAL NG unit upon coming off Active Duty. (Credit: Family Archives)

He instructed CPT Dawn to “ensure her crews received an adequate local area orientation… and that all her crews flew from Soto Cano to Macora, both day and with night vision goggles “because he expected the majority of MEDEVAC missions to be flown from Macora since that was the location of the heavy engineer equipment and road-building project.”

How to kill an aircrew and then cover it up

When informed during his interview that 1LT Boyd’s NVG credential had run out of currency (shortly after her arrival in Honduras), the battalion commander said “he felt, however, this was probably due to weather (April/May) as the end of April and the first week of May had very poor flying weather, and “very little could be accomplished.”

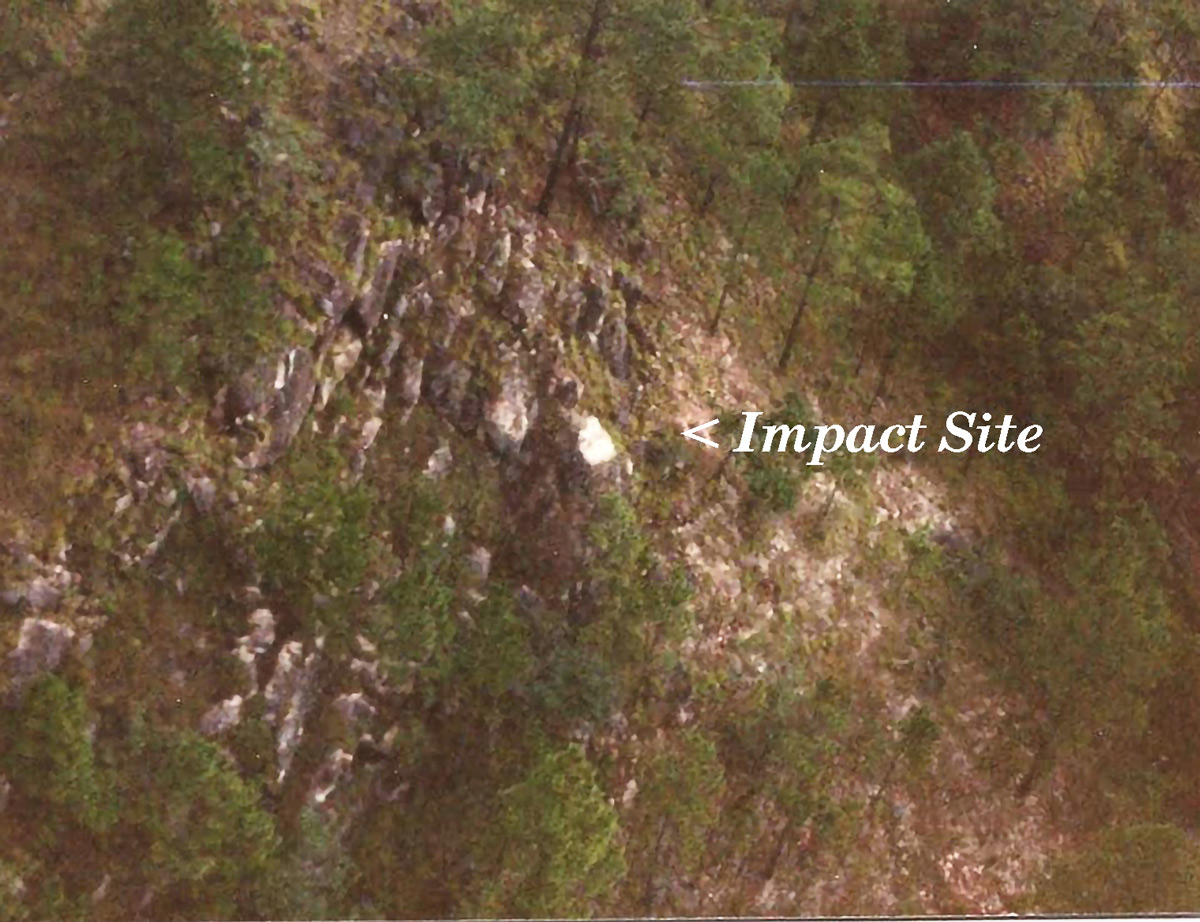

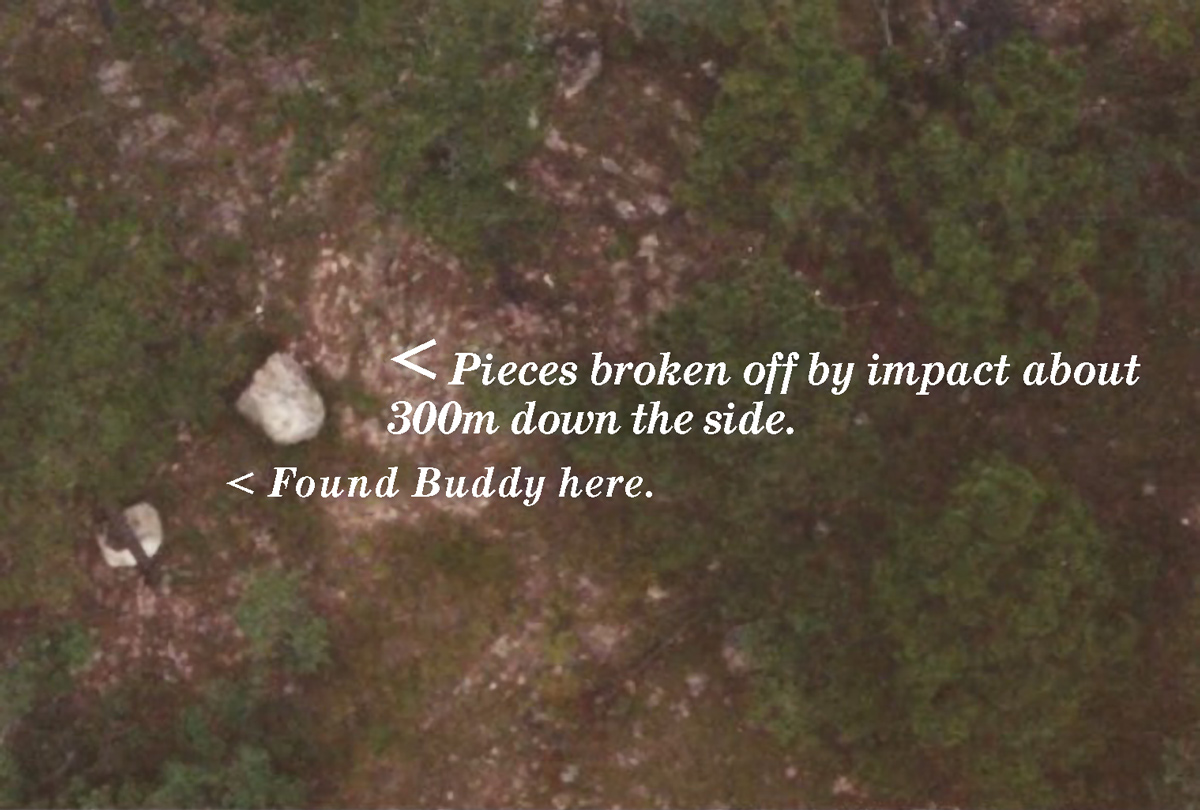

UH-1H/#640 impacted a massive mountainside boulder at over 100 knots. One investigator told survivor SPC Buddy Jarrell, the crew chief that night, it was the worst aircraft crash he’d seen in 30 years on the job. (Credit: Buddy Jarrell)

The commander of the 126th Medical Company, the parent unit for the detachment serving in Honduras, told accident investigators that all those deployed had accomplished check rides and other pre-deployment preparations so these “wouldn’t arise while they were in-country.” Still, the commander informed investigators CPT Dawn had verbally reported to him that the three crews’ orientation upon their arrival was limited. Dawn elaborated saying the orientation was not as extensive as she believed it should have been to include orientation flights where the crews were simply passengers in a Blackhawk and the promised Instructor Pilot, a pilot (IP) who is a highly experienced aviator and is responsible for training and evaluating other pilots, and an IFE, or In-flight examiner. An “Instrument Flight Examiner” is a pilot who is qualified to evaluate the instrument flight proficiency of other pilots.

This was a major issue for CPT Dawn as, per the accident report, “The unit had scheduled an IP to go with the detachment to Honduras, but a week prior, a decision was made not to send an IP because they [the 126th Medical Company at Fort Bliss] understood that an IP and IFE was available in-country.”

The 126th unit commander stated he had flown with both crew members [CPT Dawn and 1LT Boyd] as an evaluator and did not detect any real problems. The crash report summary of this conversation offers he (the unit commander) was not uncomfortable with the crews deployed to Honduras “however, he probably would not have attempted the mission with the crew that suffered the accident.” It is noteworthy that the summary does not present any narrative as to why the unit commander felt this way given his laudatory observations made earlier. For example, was he referring to the pilot/co-pilot? Or was he referring to a nighttime MEDEVAC attempt which the pilot/co-pilot had not been properly orientated for by the 4/228 due to poor weather in April and early May and the fact 1LT Boyd was not re-certified NVG wise by the 4/228th despite this capability crucial to MEDEVAC operations? And why did the XO recall Dawn’s crew rather than alerting the 2nd Up crew? And why provide them with a conventional UH-1H which unlike MEDEVAC UH-1Vs did not have radar altimeter capability? The context of the 126th unit commander’s remarks was clearly missing in the summary of his interview.

1LT Vicki Boyd, copilot, was a well educated and capable flight scheduler and aviator. (Credit: Family Archives)

The unit commander stated he was unaware of which Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) the detachment was to use “but thought it was the 507th’s, integrated with the 4/228th’s.” In short, he had no idea as to which MEDEVAC SOP the three deployed air crews fell under command and control wise. He did say CPT Dawn had called him about crew selection two weeks earlier and he had told her what to take into consideration. He was under the impression “that the Medical Detachment belonged to, and was to take its guidance, from the 4/228th Aviation Regiment.”

The 126th unit commander had 5,500 total flight hours and departed CONUS on May 14th to meet with the unit at Soto Cano Air Base.

SSGT Linda Simonds was an extraordinary flight medic and well liked by her peers. (Credit: Family Archives)

Nowhere in the accident report is found any documentation or interview summary detailing 4/228 sponsored orientation flights other than a “ride-along” by any of the three crews to include either daylight or nighttime NVG assisted flights to the TACAN site on Cerro la Mole, just 9.2 miles from Soto Cano.

Host unit negligence and a weak executive officer

The NVG issue is a significant factor in what occurred on May 13th, the night of the accident. The 4/228 did not do much flying in April/early May, and because an in-country IP was unavailable to the crews, 1LT Boyd’s NVG currency lapsed once in-country. Per Army Aviation regulations night vision goggles (NVGs) are not allowed on an aircraft if even one crew member is not NVG current, as night vision operations require all crew members to be trained and qualified to ensure crew coordination and safety. The non-current crew member cannot safely operate or assist in an NVG-assisted mission, as they lack the necessary training for the modified environment and the use of the equipment.”

On the first MEDEVAC attempt to TACAN the effort was made during the early hours of evening and was flown under Visual Flight Rules, or VFR. Meaning—the pilot is flying by visual reference to the ground and sky without relying on instruments. It requires pilots to maintain a certain distance from clouds and have adequate visibility, with specific weather minimums that vary depending on the airspace class.

4/228 UH-1H #640 at Soto Cano just days before its fatal crash on May 13, 1991 at Cerro la Mole. #640 was a conventional aircraft with no MEDEVAC specialty configuration nor the crucial radar altimeter capability necessary for MEDEVAC missions. (Credit: Ken Kik)

At approximately 2130H the medical officer on duty for the Soto Cano Hospital received had received a call from the TACAN radar site. The caller offered a 28-year-old black male was complaining of back pain and a swollen abdominal area and a MEDEVAC flight was requested as a favor rather than arranging ground transportation. Although the soldier’s reported illness was not life, limb, or vision threatening the first MEDEVAC attempt launched but returned to base due to poor weather. Upon discussion with the chain of command ground evacuation was authorized. Thirty minutes later the physician on duty was notified a second air evacuation was being attempted per the authorization of the 4/228th XO. At 2300H, the doctor re-contacted TACAN and asked if the MEDEVAC had been completed? When told no, he called Warrior Operations and it was only then, an hour and a half after the second launch, the doctor was told all contact had been lost with the aircraft shortly after take-off.

CPT Dawn had aborted the first launch and returned to Soto Cano roughly twenty minutes after take-off. This due to heavy cloud cover at 3500 feet in and around Cerro la Mole. The TACAN site elevation was 6, 447 feet. Per the accident report her decision was accepted by the unit’s executive officer who was the OIC that night given the 4/228 commander was on mid-tour leave/absent from Soto Cano.

Note: During research for this story the identify of the executive officer (XO) that night was established. As the Army crash report redacted the majority of names of those interviewed, per policy, the author has chosen not to identify the XO although the families of those lost have been duly informed of his identity.

When the XO initiated and authorized the second and fatal attempt just hours later that night, CPT Dawn informed him of 1LT Boyd’s NVG currency being out of date. This meant no one on CPT Dawn’s aircraft could have onboard or use night vision assistance for a second attempt. According to the air traffic controller (ATC) at Soto Cano that night, and contrary to the urging of the 4/228 XO that the weather had cleared to the degree a second attempt could be made, “the weather was bad and the TACAN site was fogged in until 0100–0200 the next morning [May 14th].” The ATC went on to describe the weather station, the tower, and the GCA facility at Soto Cano Air Base was calling the TACAN site “every 10–20 minutes questioning them about the weather at the site.” Although ground evacuation had been authorized and was being arranged and the medical officer on duty at the hospital clearly did not consider the reported illness/injury to be life-threatening given his communication with TACAN ninety minutes after the second launch had occurred, it becomes evident a great deal of command pressure was being channeled through the 4228th’s leadership to make the MEDEVAC happen.

Impact site (white) of Dustoff 01 as taken by flight medic Ken Kik in a later deployment. (Credit: Ken Kik)

After the fog cleared TACAN’s lookout in its tower reported seeing a fire to the south of his position. No one at TACAN had been made aware all contact with the aircraft had been lost at 2255H. TACAN’s ability to accurately describe the weather conditions from its location was minimal. They could see only what the weather conditions were at the site and above it. They could not see what conditions (cloud cover, for example) existed below their line of sight.

Pushing the limits and pressuring the pilot for no good reason

Per the 4/228th’s MEDEVAC SOP “The approval to launch MEDEVAC rests with the 4/288th chain of command…the OIC, Communications Center and JTF-BRAVO will ensure that MEDEVAC request procedures are followed and that missions are transmitted per this SOP…[and finally] The 4/228th Commander will ensure compliance with this SOP and resolve problems between the MEDEVAC section and other JTF-BRAVO elements.”

In the summary interview with a 4/228th officer and pilot (1000 flight hours) he told investigators the MEDEVAC crew, S-3 Operations Officer, and other personnel discussed and concurred with CPT Dawn’s decision to abort the first attempt as clouds were encountered at 5,500 feet. CPT Dawn determined she was not going to climb any higher since the elevation/landing pad at TACAN was 1200 feet higher with no visibility noted at the decision point to abort.

At 2115H, according to the CQ log, the Emergency Operations Center with the 4228th acting commander (XO) in concert contacted Warrior Operations stating a directive from the 4/228th chain of command to monitor the weather as a second attempt would be authorized if it cleared. At 2125H, Warrior Operations called TACAN and was told they had three miles visibility and a 1500-foot ceiling. However, in the ATC’s statement he confirmed TACAN was socked in below the TACAN site with harsh weather and was not predicted to see any change until 0100–0200 in the morning.

The accident report itself states in its Role of Weather section (DA Form 2397-11-R) “The accident occurred at night. The moon had not risen and with a 500-foot overcast condition with haze and smoke, most likely the horizon was not visible to the crew.”

Crash site located in the early morning hours on May 14th by a four-man QRF from JSOC/the 2nd Bn, 7th Special Forces Group and SPC/flight medic Ken Kik. (Credit: Ken Kik)

Specific online aviation weather data (such as a METAR report) for Soto Cano Air Base on May 13, 1991, is described as:

General Climate and Aviation

Context

- Wetter Season Start: May 13th is the beginning of the wetter season at Soto Cano Air Base, which typically lasts until late October. The chance of a “wet day” (at least 0.04 inches of precipitation) is 27% or greater during this period.

- Typical May Weather: May in Honduras is generally warm to hot, with an average daily high of around 89.4°F and a low of 71.1°F. The climate often involves a mix of partly cloudy to mostly cloudy skies with a chance of showers.

- Night Flying Conditions: One search result mentions that a helicopter crash on this date was attributed to “nighttime flying conditions in difficult terrain.” This suggests that visibility or terrain challenges may have been a factor in some operations around that time, possibly due to darkness or cloud cover.

- On May 13, 1991, the moon was in a Waning Crescent phase with an illumination of approximately 1%. The new moon occurred on the following day, May 14, 1991.

Further —

- Location and Mission: In 1991, the 4-228th Aviation Battalion was headquartered at Soto Cano Air Base, Honduras, with a mission to support U.S. military groups in Central America through air assault, air movement, MEDEVAC, and contingency operations. The environment was considered a “low intensity conflict” zone.

- Operational Context: The unit faced challenging conditions, including adverse weather, jungle, and mountainous terrain, and possible insurgent/bandit activity.

- Night Vision Goggle (NVG) Use: Operation Just Cause in Panama (Dec 1989), which involved elements of U.S. Army aviation and occurred shortly before 1991, is noted as the first time night vision goggles were used in actual combat operations. This indicates that NVG operations were a relatively new and evolving aspect of general Army aviation practice around that time, and specific SOPs would have been critical for their safe and effective implementation.

- Training Concerns: An Army report from around that time, specifically concerning crashes in Panama in February 1990, cited concerns about corner-cutting on pilot training and an “erosion of skills and confidence,” leading to potential pilot error. This suggests that unit-specific SOPs would have been essential for maintaining safety standards, a 4/228th SOP included in the accident report which the unit did not follow leading up to and including the night of May 13, 1991.

An unnamed 4/228th officer/pilot told investigators that two (names redacted) unit officers “talked with the PIC [CPT Dawn] about aided versus unaided flight and the PIC indicated she felt comfortable going unaided.” Upon learning from Dawn her copilot’s NVG currency was out of date the XO offered another pilot who was current. It was then that CPT Dawn offered she wanted to keep her crew together but required a replacement aircraft as hers had a malfunction light come on during the return flight to Soto Cano earlier. A UH-1H from the 4/228th was made available (#640) and reconfigured for MEDEVAC equipment.

The second attempt was launched with the XO’s authorization. It should not have been. Whether a fire team leader, squad leader, platoon sergeant, or platoon leader/company commander your job is to prevent your troops from doing something contrary to regulations, policy, procedure, and SOP. This did not occur between the XO and CPT Dawn—in fact, just the opposite took place per the accident report.

At 2250H, an interviewed officer stated he monitored two transmissions by 1LT Boyd which were made in a strained voice. She is reported as saying “Left bank,” and within seconds, “There are 26 pounds of torque.” At this point, according to crew chief and survivor Buddy Jarrell, UH-1H 640 impacted a massive boulder at over 100 knots and with over one hundred Gs of force. The accident report reflects the internal communication traffic as listened to by the tower personnel.

What happens to the human body

- For brief moments: A brief pulse of one hundred Gs, lasting only milliseconds, can be survivable, though still potentially causing severe injuries.

- For longer durations: Sustained 100 Gs of force would be fatal, crushing the body’s internal organs and overwhelming the circulatory system.

The impact force was so immediate and high that all three females’ pelvises were crushed. These types of forces are encountered in high-energy, blunt-force traumas such as motor vehicle accidents, falls from significant heights, or crushing injuries.

#640 impacted head on with this massive boulder while attempting to evade crashing into Cerro la Mole to the north. Bits of wreckage are indicated and the resulting fire was so intense heat-wise that metals melted/fused together. (Credit: Ft. Rucker Accident Report)

The 4/228th officer concluded his statement saying “the decision to launch the second attempt at the MEDEVAC mission was really more the PIC’s than any other individual. Command pressure to complete the mission did not exist [Italics mine].”

Those familiar with writing and reading official reports might recognize the word-play in this statement, particularly the emphasis regarding Command pressure not being a factor whatsoever.

The accident board concluded that the crash was human error—individual failure. Specifically, “The pilot’s actions were the result of her overconfidence in her own ability to fly the aircraft and assist the copilot with navigation. The copilot appeared to be disorientated as to their location and the location of the road they wanted to follow.”

However, the findings also pointed out a fraction of the 4/228th command failures to have followed its own MEDEVAC SOP. In its second Finding the board stated Present but not Contributing to the accident was this. “The local area orientation provided the 126th Medical Detachment on arrival in-country was inadequate and not in accordance with the 4/228th Aviation Regiment Standard Operating Procedure (SOP). Some unit members received no orientation or a partial orientation while others received theirs as a passenger in a UH-60 aircraft where they were unable to see and navigate. Also, they had not conducted the night vision flight to and from Macora as directed by the battalion commander.”

The board made it clear “The Findings listed below did not contribute directly to this accident; however, if left uncorrected, they could have an adverse effect on the safety of aviation operations.” The accident report included a statement that no other or further investigations were necessary despite the investigators knowing a collateral board was required due to the loss of life directly connected to the crash.

In short, the board’s conclusions and placement of blame on the pilot /copilot was an unmitigated lie meant to protect the truly responsible parties involved. The report omits eye-witness accounts to conversations at Soto Cano regarding command pressure; offers subjective private opinions of CPT Dawn in specific; presents critical factors as fact that are refuted by the survivor and flight medic Ken Kik; and is a report slanted in bias. Meaning it is an official account that selectively chooses information or data to support one side and that side was the 4/228th Aviation Battalion at that point in time.

The most glaring as well as unpalatable example of in-house bias and inaccuracy at the 4/228th comes from a former company commander at the unit who had interacted with CPT Dawn at briefings. The officer, in a 2025 email, stated “The 126th Med. Co. only arrived in Honduras on April 17, 1991. They were NOT serving in a conflict or with an active hostile force…Even the Official US Army Accident Report (910513-2312-6815640 (Copy-C) dated 23 Dec 1991) confirms there was no hostile threats to the mission and the crew did not fly with weapons or was the crew armed.”

Factually the U.S. clandestine/covert war in Honduras had been going on for over ten years. The Contra War was just winding down in 1990. Soto Cano SOPs in May 1991 made it clear no U.S. personnel could travel outside the gates unless they had a fully armed MP escort and a very good reason to do so. Finally, Buddy Jarrell, the sole survivor, affirmed with the author that he’d drawn his M16 for the mission and the pilot, copilot, and flight medic were likewise armed, per MEDEVAC policy, with their sidearms. And the report itself states the Threat level was “Low—None”.

Note: What it signifies:

- High Security/Stability: The region is considered stable, possibly friendly territory, or an area with overwhelming air superiority.

- Reduced Risk: Enemy air defense systems (SAMs, AAA) are likely absent or ineffective, and enemy aircraft aren’t expected to contest the airspace.

- Mission Focus: The mission can focus purely on its objective (delivery, reconnaissance, VIP transport) without extensive counter-threat measures.

What it doesn’t mean:

- No Hazards: It doesn’t eliminate all dangers, such as weather, birds (BASH), or accidental encounters, but it removes the man-made threat of attack.

- Total Complacency: Crews still maintain situational awareness (SA) and follow procedures; “low” still means some potential exists, even if extremely remote.

In simple terms: “Go fly; we don’t expect anyone to shoot at you, but keep your eyes open anyway.”

Throughout the 1980s the U.S. conducted a counter-insurgency operation in Honduras against both internal and external (Sandinista Nicaragua) threats. By 1990, the Contra War was ending and along with it U.S. military support to include a history of cross-border operations from southern Honduras across the border into Nicaragua. These were most often conducted by 2nd Battalion, 7th Special Forces, then stationed at Soto Cano and JSOC Special Mission Units (DELTA/SEAL Team SIX). It was not uncommon for MEDEVAC crews to mask their aircraft ID markings and fly, fully armed per MEDEVAC SOP, into Nicaragua to evacuate wounded SF combat advisors or CIA officers.

U.S. Army MEDEVAC aircraft, during the ten-year insurgency and Contra war mounted from southern Honduras, would often strap M-60 light machine guns to the deck when entering Nicaraguan air space to rescue/recover U.S. personnel advising the Contras. They were not mounted but rather “carried” and could be used if necessary by the crew chief in hand-held mode.

Per the survivor, CPT Dawn and her crew were armed per SOP and in fact then SP4 Jarrell’s M-16 was recovered, bent into the shape of a “U”, at the crash site.

The report’s mission briefing statement clearly states the Threat level on May 13th was “Low – None”. And the JTF-BRAVO SOP during this same time period restricted any U.S. travel outside Soto Cano, especially at night, without a fully armed MP escort. Further, the TACAN site featured a platoon of MPs, again fully armed, to ensure the safety of the site and its personnel from insurgent attacks. As for accident report stating the crew was unarmed as claimed, a response to my query to the Fort Rucker FOIA team affirmed accident investigators/reports do not mention or account for weapons or munitions. And MEDEVAC regulations/policy states crews can fly armed with personal weapons which CPT Dawn and her crew did. This given the still uncertain nature of the environment bandit/insurgent wise.

The Army MP platoon at TACAN was fully armed as a perimeter security force. (Credit: AFEM for Honduras FB page)

But it is this retired officer’s comment regarding CPT Dawn, sent in an email thirty-four years after the crash, which illuminates the dark side of the unit culture at the senior leadership level in the battalion regarding not only the 126th Medical Detachment but female aviators such as CPT Dawn and 1LT Boyd.

“As a Captain, I attended the staff meetings with CPT Dawn periodically after her arrival and before the accident. From my encounters with her she was definitely headstrong, a bit cocky and didn’t like to be crossed or questioned. She was what I would call “Hot-Crazy” Definitely a hot 10, but also a bit crazy–scary!”

D. Joyner, who served at Soto Cano and knew the aircrew, posted this good-hearted and complementary observation on the AFEM for Service in Honduras FB page:

“I was there as well, CPT Dawn and crew was way too nice to a bunch of Freight-Train PFC’s always trying to pick em up at the Blackjack club. Very classy with her rejections, lol.”

Several now retired Army aviation pilots the author spoke with offered this keen insight. Female aviators have always had to work twice as hard as their male counterparts to earn respect. Mr. Joyner’s recollection illustrates the other obstacle they faced and addressed professionally.

Note: CPT Dawn was not located by the JSOC team and flight medic Ken Kik at the crash site. It was felt she had either been thrown further away from the point of impact or, according to the accident report, captured. The report notes the capture of a Honduran national by the MP element on the road below the crash site in the early morning hours. The Honduran was turned over to the host country police authorities. It is unknown why he was inside the perimeter and attempting to avoid detection. A former MP who was stationed at Soto Cano at this time described to this author that Honduran nationals were a concern and frequent encounters with them by the MPs took place. “We never knew if they were looters, or bandits, or insurgents, or just showing up because they were curious,” he said.

Dawn’s remains would not be discovered until the tail boom of the aircraft was x-rayed at Soto Cano by the Fort Rucker investigation team. She had been dismembered upon impact and her torso, burnt beyond recognition, had been forced from the cockpit back through the passenger compartment and into the tail boom itself.

1LT Boyd’s body was discovered by the JSOC team and flight medic Ken Kik. According to Kik it was clear she had survived the crash although thrown 225 feet, still in her seat, downhill. Kik described it was evident Boyd had gotten herself out of the seat, removed her helmet, and then crawled/fell twenty-five feet further downhill. Because the 4/228th XO refused multiple times to launch a MEDEVAC immediately upon the discovery of two possible survivors on the mountain, Kik believes 1LT Boyd died of her injuries during the hours after the crash and the JSOC team getting onsite. According to Kik, had he been hoisted into the crash site much earlier Boyd may have had a fighting chance to survive her injuries. It was 1LT Boyd survivor Buddy Jarrell heard calling for help as he lay three hundred yards downhill, gravely injured and surrounded by the torrent of flames the aircraft’s punctured fuel cell was feeding.

SSGT Simonds was killed upon impact. SPC Kik located her body on the mountainside.

SPC Buddy Jarrell was thrown over 300 yards down the mountainside. That he survived his injuries, recovered from them, and remained on Active Duty until his retirement (E7) is a miracle in and of itself.

The officer’s subjective comment as quoted is indicative even years later the culture at the 4/228th was biased as well as unacceptable as held by certain members at the command level.

Due to name redactions, it is possible but unknown if this individual was interviewed for the accident report, or in some other manner contributed his disparaging thoughts regarding CPT Dawn and/or 1LT Boyd. Regardless, they demonstrate serious unit cultural problems at that time and the practice of laying blame on the doorstep of the dead.

The hand-drawn illustration from Buddy Jarrell of the crash. The “OOO” is #640 as it banked hard left to avoid impacting Cerro la Mole. The helo swiftly lost altitude while gaining speed and barely avoided crashing into a cliff face on the western side of the valley. CPT Dawn regained control and began to climb but by then it was too late. #640 impacted the eastern cliff face at over 100 knots (the report offers 90 knots but Jarrell was told by an investigator their air speed was higher). (Credit: Buddy Jarrell)

A public relations nightmare

The fatal crash of a MEDEVAC aircraft in Honduras was front page news. In addition, that three female aviation personnel were killed drew even greater attention. The personnel files of all three women were requested by both media and congressional members. The accident report’s conclusion, that CPT Dawn became distracted while attempting to assist her copilot with navigation duties and by doing so flew into the side of a mountain made it a cut and dried event. Pilot error. No more, no less.

In 2025, SFC (ret) Buddy Jarrell recalled what truly occurred adding much of his official statement to investigators was heavily edited.

Jarrell offered CPT Dawn flew to La Paz as they could see the town’s lights. She was hoping to find the road that led up to the TACAN site and simply follow it. They did find the road per both Jarrell, who was lying on his belly looking down and using the aircraft’s landing light for illumination, and the internal communications traffic between Dawn and Boyd as presented in the report.

They had made several attempts to fly up the valley but the terrain and tree cover made it impossible to keep the road in sight. Jarrell recommended to CPT Dawn that they abort the mission as it was becoming too dangerous. Dawn’s response was curt, adding they would try one more time. Jarrell recalls seeing Cerro la Mole appearing right in front of the aircraft. Dawn made a sharp adjustment to the left, placing the aircraft at an estimated 30-degree angle. The MEDEVAC helo began losing altitude while also picking up speed. They missed impacting into a cliff on the west side of the valley, but as Dawn regained control of their decent and began to climb they crashed into the cliff side on the east side of the valley.

Note: The report states CPT Dawn never located the road. But elsewhere in the report the internal communications traffic between pilot and copilot states clearly they had. And Buddy Jarrell’s recollections decades later confirms the road was indeed, for a very short period of time, located and attempted to be followed.

Jarrell remembers trying to push SSGT Simonds into the crash position but she kept sitting straight up. “There was a lot of screaming over the headset and then the next thing I knew I was lying on my back, in the dark, watching a river of fire coming downhill toward me from the punctured fuel cell. I heard someone, I thought it was Linda, calling for help. There was nothing I could do but yell back that help was coming.”

Part II — Crash survivor William “Buddy” Jarrell and flight medic Ken Kik tell their stories for the first time in 34 years.

Ken Bowra and Greg Walker (Photo Credit: Greg Walker)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR — Greg Walker is an honorably retired “Green Beret”. He served in El Salvador in the 1980s and during Operation Iraqi Freedom. His awards and decorations include the Combat Infantryman Badge (X2), the Special Forces Tab, and the Legion of Merit. Upon retirement Greg returned to college and in 2009 began working as a case manager and patient advocate for the SOCOM Care Coalition. Today, fully retired, Mr. Walker lives and writes from his home in Sisters, Oregon, along with his service pup, Jasper.

The Reconnaissance Cast: Greg Walker- Interview with SF historian and 7th Special Forces Group Vet

Bud Gibson’s YouTube channel “The Reconnaissance Cast” is a fantastic resource for those interested in firsthand accounts from MACVSOG/FORCE RECON and Aviation Veterans!

Leave A Comment