A LEGEND

Before His Time:

“CHARGIN’ CHARLIE” BECKWITH

Before His Time:

“CHARGIN’ CHARLIE” BECKWITH

By Irv Jacobs and Ben Rapaport

Introduction

“Chargin’ Charlie” Beckwith was destined to become a Special Forces legend. Introduced to the Army at an early age—he watched polo matches at Fort McPherson, Georgia and dreamed of an Army career—he later turned down an offer from the Green Bay Packers in lieu of commissioning from University of Georgia ROTC. While Charlie would never reach the status of general officer—he was too much of a maverick and burned too many bridges behind—his foresight, courage, and perseverance would earn him a coveted place in the annals of the Special Operations community, writ large.

That said, this article is not a typical replay of Charlie’s exploits, as exceptional as they were. While we have chosen to briefly recount the highlights of his career chronologically to show his impact on special operations, our intent is to focus as well on how Charlie the man engaged, contributed, and reacted to them. To accomplish this, we have presented, in italics, our personal anecdotes related to Charlie, while the general historical facts remain in normal typeface. The first italicized entry from each of us bears our names; thereafter, only the initials are used. The historical facts are generally well-known, and have been drawn primarily from online sources such as Wikipedia, togetherweserved.com, government documents, and Charlie’s obituary. We take full responsibility for the accuracy of this narrative.

Early Career

Charles Alvin Beckwith was born in Atlanta in 1929 and went on to become an all-state football player in high school and a three-year starter at guard for the Georgia Bulldogs. Commissioned in the Infantry in 1952, Charlie spent several years in conventional units, first as a platoon leader in the 17th Infantry Regiment, 7th Infantry Division in Korea following the conflict in that theater, and then as a company commander in the 82nd Airborne Division.

After graduating Ranger School in 1958, Charlie’s fortunes turned and his ascent in Special Forces and special operations was launched. Charlie would eventually become known for establishing 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment, Delta (Delta Force) and, ironically, through the failure of Operation Eagle Claw, indirectly contributed to the institutionalization of joint special operations.

Volunteering for Special Forces and assigned to the 7th Special Forces Group (Airborne) after Ranger School, Charlie deployed to Laos in 1960 as an adviser on Operation Hotfoot (later merged into Blue Light). In 1962, Charlie embarked on an exchange tour with the British 22 Special Air Service Regiment that was to define the remainder of his career in special operations.

The Genesis for Delta Force

At that time, U.S. Army Special Forces engaged almost entirely in unconventional warfare and foreign internal defense, providing advice and assistance to indigenous forces and training them in resistance operations. He deployed with the SAS in the Indonesian Confrontation (and, in the process, contracting leptospirosis which he was not expected to survive), became enamored with the SAS’s practices in organizing, assessing, and selecting personnel, their tough, realistic training, and their execution of counter-terrorist tactics and techniques.

Upon returning from service with the SAS, as a captain, he began a long and, initially, unsuccessful campaign of requesting that U.S. Army Special Forces establish a unit along the lines of the SAS, with direct action included in its missions. His voice went unheard for more than a decade.

The Interim Period

Instead, returned to the 7th Group and, in 1964, promoted to major, Charlie became the Group S3 and set out to change the way that Special Forces trained based on the SAS training and operational model. It was at this juncture that the authors first came to know him and came under his influence.

Ben Rapaport (BR): Having joined Special Forces in Spring 1963 as a 1st Lt., assigned as the 7th Group S-2 (Training), I noted that HQ personnel were anticipating Charlie’s imminent arrival from the UK. I did not know why, because everything and everyone were new to me. Then, one day in he walked. I was staring at a six-foot, three-inch muscular man of few words who spoke rapid-fire in a slight Southern drawl. It did not take long for me to recognize that he was an extraordinary officer, motivated, accomplished, and as serious as a heart attack. For whatever reason, Charlie took a liking to me and began calling me Rap.

Irv Jacobs (IJ): Shortly after Charlie became the S3, I was reassigned from command of an ODA to serve as the Group’s Assistant S3 (Training) becoming, in effect, an agent for converting Charlie’s training ideas and practices into reality. (He called me Jake.) The core of these was to establish a training base near Blowing Rock in western North Carolina, some 150 miles from Fort Bragg, and to rotate the Group’s detachments through it for week-long, diversified, hard-nosed training in the rugged terrain of the surrounding Pisgah National Forest. As a hands-on officer, Charlie could frequently be found roaming the Pisgah terrain checking the training or meeting with his team at the Blowing Rock site to critique it, always with his signature cigarette dangling from his lips.

This training became consequential for the Group’s detachments and personnel that had already begun deployments to Southeast Asia and which were to continue—albeit not under 7th Group command —for the next decade.

BR: It had been well-established that Charlie was always thinking outside the box, always striving to revolutionize SF training. The Pisgah deployment would be unconventional warfare training in which the ODAs would wear civilian clothes, blend into the community, live among them.

He stated one objective to me: “Rap, I want the teams to be able to send and receive encrypted voice traffic using other than our military-approved frequencies. You’re a Signal Officer … make it happen.”

Still a First Lieutenant, this was way beyond my skill set and authority, but I knew this much: the NTIA (Department of Commerce) manages the U.S. Military’s radio spectrum; the FCC, an independent agency, allocates specific frequency bands for amateur and Ham radio operators; and MARS is a DoD ham-radio program. I went to Washington, D.C., met with the FCC, explained the exercise and the importance of Charlie’s unusual objective. I returned to Fort Bragg with written approval that, for the duration of the exercise, ODA radio operators can use MARS radio frequencies to transmit and receive encrypted voice and Morse-code messages. Additionally, MARS operators will be authorized to send and receive Team messages, if asked to do so. I’d just earned another Charlie attaboy.

IJ: It was during this same period that the authors began to know Charlie better and be afforded brief glimpses into his personal life. His sometimes-gruff exterior masked an inner depth of feeling for his fellow human being, but always in the context of accomplishing the mission. And according to Beckwith folklore, when the mission involved extended training in the field – such as the Pisgah training – his family – his wife and three daughters – were not exempt from his dictates: he required them to eat C-rations during his absences.

BR: What I best remember were two things about this Pisgah training. Charlie believed many of us needed better skills in land navigation so, before we deployed, he said, “Rap, find me maps of our exercise area that do not have a UTM grid.” Huh? Well, after a little homework, I learned that they exist, and I obtained raised-relief maps from the U.S. Geological Survey for the participants. (That earned me yet another attaboy from him.) One evening, sitting with Charlie on a forest mountain top, he revealed his personal views of Army service. He asked: “Rap, are you married? “No Sir.” He said: “The Army and marriage don’t mix well.” “Rap, are you religious?” Not very, Sir.” He said: “The Army and religion don’t mix well.”

IJ: From the 7th Group, Charlie volunteered to return to Southeast Asia (Vietnam) in 1965. By this time, both Ben and I were serving in the 5th Group, Nha Trang, Ben commanding the Group Signal Company and I, just having been elevated from a ‘B’ detachment to the Group staff as the S1 (adjutant). (The Group was Provisional until early1965.) Charlie, however, was not slated to join Special Forces in-theater, so one fine day in mid-1965 I received a phone call from Charlie (not yet deployed) pleading to be assigned to the Group – “Jake, ya’ gotta’ get me into SF!” Pulling some strings, I did manage to accomplish that feat, and when he deployed to Vietnam, he was assigned to 5th Group and given command of Project Delta, a highly-trained force of primarily Chinese Nungs that conducted long-range reconnaissance and quick-reaction operations for the Group.

BR: The singular event that still sticks with me is that I flew from Nha Trang to Tan Son Nhut Air Base, Saigon, to meet Charlie on his arrival in country and escort him to Nha Trang. I could not believe my eyes. He exited the commercial aircraft wearing our exclusive jungle fatigues carrying a rucksack and an AR-15. Before I could ask how had he managed to take a weapon from a CONUS arms room, he volunteered: “I zeroed in this weapon at Fort Bragg, and I have no intention of letting it go.”

IJ: Immediately upon taking command of Project Delta, Charlie began to clean house among the existing SF cadre whom he deemed as unfit, but all of whom he would have to replace. In a burst of imagination, he composed a flyer that he wanted to send out to all SF units in the Group soliciting replacements. The flyer, in addition to listing the requirements Charlie established for the volunteers, read: “WANTED: Volunteers for Project DELTA. Will guarantee you a medal, a body bag, or both.” He ran the flyer by me and the Group commander; the latter was of the opinion that there would be no takers. On the contrary, Charlie had to turn people away.

The most well-known of Project Delta’s operations that Charlie led was the successful reinforcement of the ODA at the SF camp at Plei Me, in the Central Highlands of Vietnam about 25 miles south of Pleiku City which, in the larger context, came to be known as the Siege of Plei Me. In addition to the ODA and its “sister” South Vietnamese special forces detachment, the camp was manned by about 400 Civilian Irregular Defense Group soldiers, local Montagnard irregulars. That battle, that began on the night of October 19, 1965, marked the first major confrontation between North Vietnamese regulars and the U.S. Army in Vietnam. It ultimately involved, in addition to U.S. and South Vietnamese SF and the forces they were advising/commanding, the 1st Cavalry Division, significant Army of the Republic of Vietnam forces, and massive close-air support, and it turned out to be the prelude to the Battle of Ia Drang which began in mid-November 1965. (President Lyndon Johnson called Charlie during the siege to congratulate him.)

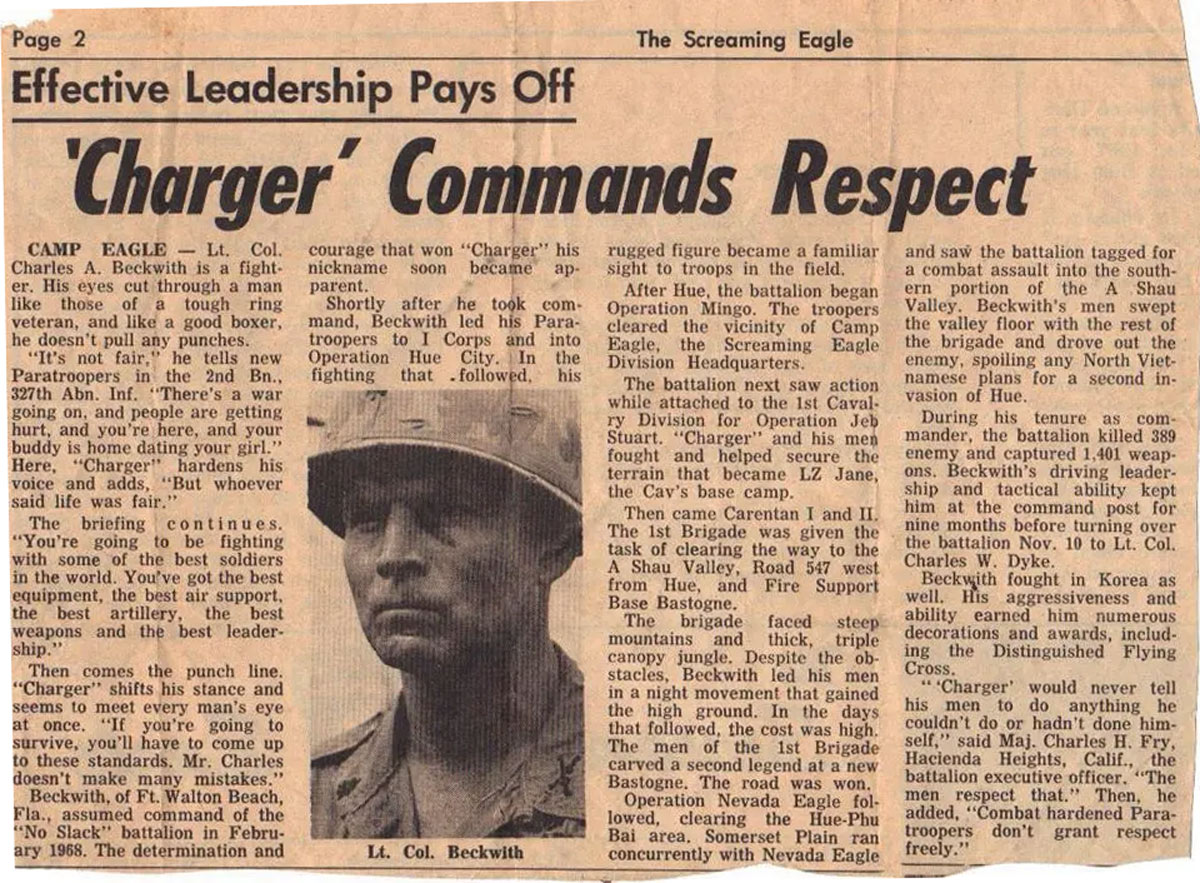

In early 1966, Charlie was severely wounded. He had taken a .50-caliber round to the abdomen and, once again, was given little chance of surviving, but was evacuated to make a full recovery. He went on to assignment to the Florida Phase of Ranger School where, in his inimitable style, he revamped the scripted curriculum to Vietnam-oriented jungle training. But this turned out to be little solace for his warrior nature and early 1968, following the Tet Offensive, found Charlie back in Vietnam, this time commanding the 2nd Battalion, 327th Infantry, 101st Airborne Division. The 2/327 was instrumental in road-clearing operations that paved the way for the establishment of Firebase Bastogne, located along Highway 547 halfway between the city of Hue and the A Shau Valley.

After a stint with the Joint Casualty Resolution Center in Nakhon Phanom, Thailand, in 1973-74, and now a colonel, Charlie returned to Fort Bragg in 1975 as the Commandant of the U.S. Army Special Warfare School, and this is where his fortunes began to rise in earnest in SOF. Beginning with his report to senior leadership after his return from SAS in 1963 which was relegated to the back burner, Charlie continued to tilt at this windmill at every opportunity thereafter, with similar results. However, his tenure at USASWS now put him in a position where he was more likely to be heard.

Delta Force is Hatched

BR: In June 1975, I was the Chief Communications-Electronics Officer, USA John F. Kennedy Center for Military Assistance, Fort Bragg; at the time, the legendary General “Iron Mike” Healy was the Commander of the Center, and Charlie was the Commandant of the Special Warfare School. One day, Charlie called stating that he was developing a special-mission unit and asked if I knew and would recommend an SF communicator for this unspecified unit. I chose SFC Angel Candelaria, my senior NCO in the office; he was interviewed and accepted. (Candelaria carried the SATCOM radio in Operation Eagle Claw.) During my tenure, there were rumors of another unit in development, Blue Light. Army DCSOPS, LTG Edward C. Meyer came to Fort Bragg, and MG Robert Kingston (General Healy’s replacement) briefed him on both developing units. General Meyer chose Delta and quashed Blue Light.

In the late 1970s, with international terrorism on the rise, Charlie was finally given the green light to form his proposed counter-terrorism unit, and in November 1977, Delta Force was officially established by Beckwith and Colonel Tom Henry, the co-developer of the unit. Delta was based on the SAS direct-action model, but included hostage rescue, specialized reconnaissance, and covert operations. It was headquartered at Fort Bragg, interestingly enough in what had been the post stockade, an already fairly secure facility.

After activation of Delta, no time was lost in implementing an assessment process from among an initial set of volunteers. Those who passed the initial screening were put through a grueling selection process in early 1978, involving land navigation problems in mountainous terrain while carrying increasing weight to test their endurance, stamina, and mental resolve. An initial training course was held from April to September of that same year, and in the fall of 1979—some two years after activation—Delta was certified as fully mission-capable, ready to perform its initial missions.

BR: In June 1996, as a LTC assigned to DCSOPS, the Pentagon, I was charged with oversight of Active, Reserve, and National Guard Special Forces communications. In September, my boss, MG Charlie Bob Myer, instructed me to join an already-established, DCSOPS-led planning committee to fund Delta. I would be the Signal representative among several Infantry and Armor officers. It was a time when DoD and the Army were seeking ways to save money. On my very first day, I was told that the proposed plan was to issue Delta handheld AN/PRC-6 and the manpack AN/PRC-10, Korea-vintage radios that had been in storage at Anniston, Alabama Army Depot for many years. I immediately left the meeting and went to my boss to report this bizarre proposal. His guidance: “Ben, do what is necessary.” I decremented an Army communications program, redirecting $6.4M to the embryonic Delta. In December 1978, I got a surprise phone call from Charlie who, in his customary terse manner said: “Rap, I got the money, thanks, and Happy Hanukkah.”

Into the Cauldron – Operation Eagle Claw

IJ: During the period that Delta Force was moving toward its goal of mission-capability, both Ben and I had retired from the Army, I then being employed by a training management firm in downtown District of Columbia and Ben by a research-and-engineering firm in the DC environs. We had not seen Charlie in several years. One day, while sauntering through the DC business district on a lunch break in early 1980, I happened to glance into a doorway on M Street and, lo and behold, saw Charlie loitering there. We reengaged, and when I asked him what he was doing lurking in the doorway of a business in downtown DC, he responded with his covert, self-effacing smile (yes, Charlie smiled occasionally!) and an innocuous response that left me scratching my head. It was only a month or two later that it became evident that Charlie—and, no doubt, several Delta operators—had been performing reconnaissance training in advance of Operation Eagle Claw.

BR: It’s hard to believe, but the Special Forces community is quite small. MSG Hugh Gordon was my First Sergeant when I commanded the Signal Company in Vietnam. He told me that he was an ROTC Instructor at the University of Georgia when Charlie was an ROTC cadet there. In 1980, retired, I was working for a Defense contractor that had the task to make recommendations to improve Delta’s communications. My firm chose me to conduct the study. As I was parking my rental car at Delta HQ at Fort Bragg, here was Hugh, now a Wackenhut employee and Delta security guard. We talked of old times, and he told me that after the Eagle Claw mission, Charlie returned to Fort Bragg, and they reunited, reminisced, and shared a bottle of Wild Turkey. As they drank, Hugh watched Charlie cry, not so much for the failed mission, but for the eight who died in the Dasht-e-Lut desert.

If Charlie was to have gone down in flames, nothing could have been more cataclysmic than Eagle Claw, the failed operation to rescue the 52 Americans taken hostage on 4 November 1979 – shortly after Delta became mission-capable – and held in the U.S. Embassy in Tehran. Volumes have been written on the whys and wherefores of that operation that took place in late April 1980, but, in brief, it failed because of unexpected weather, maintenance problems within the helicopter contingent, command-and-control problems among the multi-service component commanders, and the tragic collision of a helicopter and a ground-refueling aircraft, resulting in eight fatalities and three WIAs. Charlie was the ground force commander for the operation, leading almost one hundred Delta Force personnel and a number of other special operators.

BR: In the early 1980s, Irv and I wound up in the same research-and-engineering firm in Northern Virginia, supporting mainly DoD agencies. In the late 1980s, Charlie was in DC. We hadn’t seen him for several years, but he knew where we worked, visited the company, and gave us an unclassified, but detailed, account of what went wrong in the desert. He still had not found himself at peace.

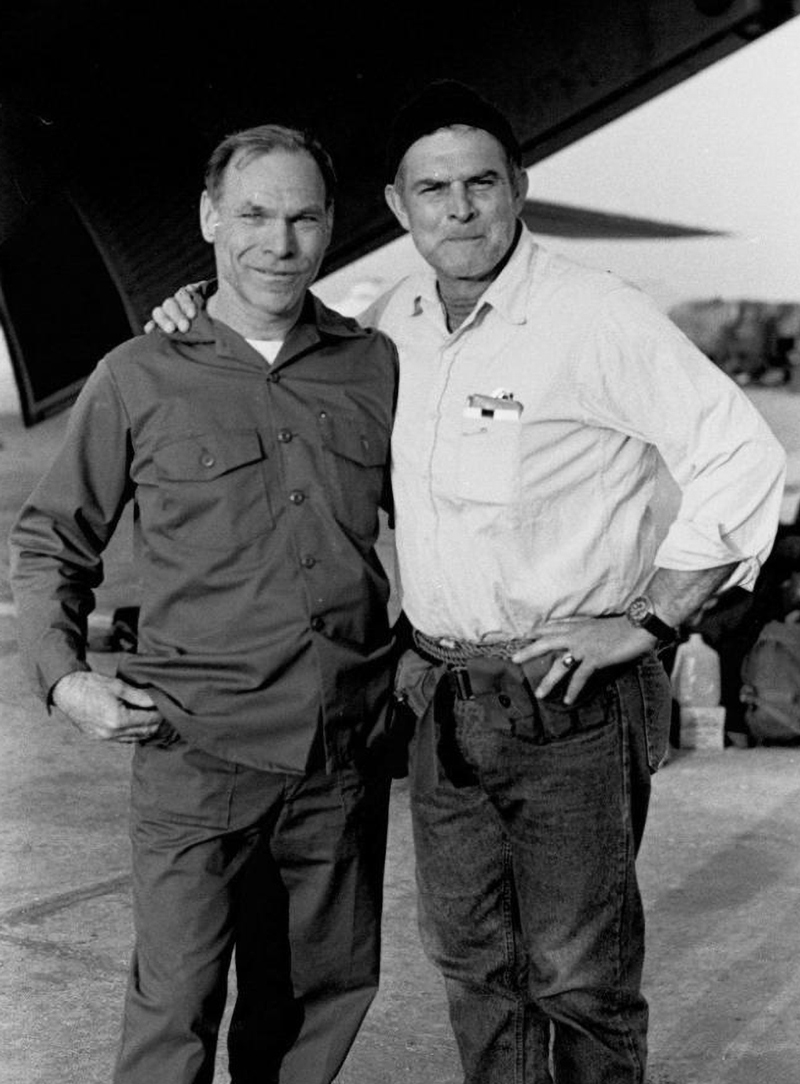

At left, Army Major General James B. Vaught, who was the Joint Task Force commander for Operation Eagle Claw, and at right, COL Charlie Beckwith, who had been appointed as the ground force commander, before the start of the mission in April 1980.

While Eagle Claw itself may have failed, it yielded some very specific force-structure lessons that have been institutionalized within special operations and proven themselves time and time again:

- Most importantly, Eagle Claw highlighted the inability of the service components to cohesively work together. This resulted, in April 1987, in the establishment of the U.S. Special Operations Command, a unified combatant command with four subordinate service component commands and one sub-unified command, Joint Special Operations Command. Delta Force, created by Beckwith, is under the operational control of JSOC.

- Creation of the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment, to remedy the lack of well-trained Army pilots capable of low-level night flying.

- Creation of the Joint Communications Unit, to standardize and ensure interoperability of the communication procedures and equipment of JSOC and its subordinate units.

Operation Eagle Claw effectively ended Charlie’s military career. Disillusioned with the outcome of the operation, he retired from the Army in 1981 and formed a security consulting firm in Austin, Texas. He died peacefully in his sleep at home on June 13, 1994, but he is definitely not forgotten. He had begun beating the drum for changes in Special Operations early in his career, and continued to do so while being thwarted at every turn. But through his foresight, initiative, and perseverance, he forever changed the nature of Special Forces training, and he ultimately created an elite counter-terrorist unit that set the bar for similar units worldwide. It’s no surprise that a November 12, 2020 Business Insider article included Charlie Beckwith as one of the “3 legendary leaders who made America’s special-operations units into the elite forces they are today.”

Charlie, The Man

Throughout his military career, Charlie was known for using colorful, graphic, often outrageous language, and it was this turn of phrase that frequently defined him. You’ll find many of his memorable quotations online, but here are just two examples. “Make a simple plan, inform everyone involved with it, don’t change it, and kick it in the ass.” After the conclusion of the disastrous Eagle Claw mission, Charlie met President Carter who thanked him, and Charlie asked if he could tell the President something. When granted permission, Charlie said, “Mr. President, me and my boys think that you are as tough as woodpecker lips” (Hamilton Jordan, Crisis. The Last Year of the Carter Presidency, 1982).

To complement this narrative, we’ve included how several others viewed Chargin’ Charlie Beckwith. The following comments from the media are listed in no particular order of relevance.

- “The mettle of the man [Beckwith] is best evidenced by his decision to abort in the desert. In militarily untenable circumstances, he unhesitatingly elected life of his command over personal martyrdom in a historical footnote. One can only speculate where a lesser soldier would have led us” (“Reader Comes to Beckwith’s Rescue,” MR Letters, Military Review, January 1984, page 69).

- “Beckwith said the mission was doomed by too much internal bickering among bureaucrats who did not have enough experience with high-risk missions. …I do regret not putting my foot down more often,” he said in 1982. But when asked if he objected to history’s portrayal of him as the leader of a calamitous mission, Beckwith replied with characteristic bluntness: “It’s the damn truth” (“Obituary: Col. Charles Beckwith; Led Failed Iran Raid,” Los Angeles Times, June 14, 1994). The New York Times announced his death on June 14, 1994: “Colonel Charlie Beckwith, 65, Dies; Led Failed Rescue Effort in Iran.” In it Charlie remarked: “It was the biggest failure of my life. I cried for the eight men we lost. I’ll carry that load on my shoulders for the rest of my life.”

- “As [U.S. Navy Captain Paul B.] Ryan (The Iran Hostage Rescue Mission: Why it Failed, 1985) puts it, once the American servicemen were inside the embassy ‘it was certain that the Iranian guards would have been met by a stream of bullets’, and in the words of ‘Chargin’ Charlie’ Beckwith—another commander of the operation—the Iranians would simply have been ‘blown’ away. When asked by Deputy Secretary of State Warren Christopher at the 16 April briefing what would happen to the Iranian captors. Beckwith reportedly replied, ‘we’re going to shoot each of them twice, right between the eyes’” (David Patrick Houghton, US Foreign Policy and the Iran Hostage Crisis, 2001, page 9). This last was in keeping with the sign that Charlie kept on his desk at Fort Bragg, which Kai Bird pointed out in The Outlier (2021, page 528): “Kill ‘em all. Let God sort ‘em out.”

- “I knew Charlie and his men—their attitudes, their skills, their competence, and their leadership—and I have no doubt that if we could have gotten them to Tehran, they would have pulled it off. There is ample evidence from former hostages interviewed that suggests that the rescue attempt would have been successful” (Eric L. Haney, Inside Delta Force, 2002, page 256). CSM Haney was a member of Delta who took part in that operation.

- “Fourteen years earlier [1980], on his dream mission, on the sands of a place named, Desert One, in Iran he [Charlie] had watched his Operation Eagle Claw go up in flames in an accidental collision of two aircraft. His Delta Force had gone on to many successful missions since that searing failure. He was tough—of mind and body—surviving severe wounds in two wars and slaying bureaucrats who stood in the way of soldiers’ needs. He was ‘old SF,’ and he was an honorable man” (John H. Corns, Our Time in Vietnam, 2009, 63). (LTG Corns and Charlie crossed paths several times during their respective careers.)

- And finally, as Colonel Jesse L. Johnson so precisely states: “That was Charlie Beckwith’s true legacy— not the failure of Eagle Claw, but the success of the changes that he fought for in its wake— changes that would save many American lives over the next four decades. He never got over it, though— Desert One” (Warfighter. The Story of an American Man, 2022, page 153).

You can see a short clip of Charlie on C-SPAN, (c-span.org), December 31, 1989, discussing the aborted mission, and listen to a 1990 online interview with Charlie at texashistory.unt.edu.

Charlie is honorably mentioned in Billy Waugh and Tim Keown, Hunting The Jackal (2004). He was awarded the USSOCOM Bull Simons Award and inducted into the Ranger Hall of Fame in 2001, into the Commando Hall of Honor in 2010, and designated a Distinguished Member of the Special Forces Regiment in 2012.

We will always remember Charlie, the man, the myth, a soldier of incredible talent, foresight, resilience, courage, leadership, and bravery, a larger-than-life American version of a British SAS operator. He was, indeed, a legend before his time. v

Postscript: Members of Charlie Beckwith’s family have read the draft of this article and have consented to its publication.

Delta Force: A Memoir by the Founder of the U.S. Military’s Most Secretive Special-Operations Unit

In this acclaimed memoir, Col. Charlie A. Beckwith tells the story behind the creation of Delta Force—the vision, battles, and hard-won lessons. He takes readers inside the formative years of America’s premier counterterrorism unit—from the bureaucratic fights to the high-stakes missions that shaped its legacy. It’s an unfiltered look at the man, the mission, and the elite force he built from the ground up.

Available for purchase on Amazon in hardcover, paperback, Kindle, and audiobook.

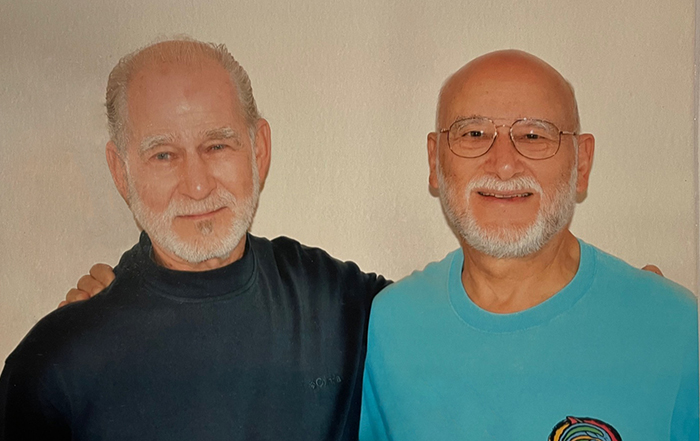

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Irv Jacobs is a retired Infantry officer, and Ben Rapaport is a retired Signal Corps officer.

Had several engagements with Charlie–Robin Sage DEC 75; he was my interrogator at Selection in APR 79; several personal stories from 80 in the unit. He was gruff, but also a superb warrior leader and kind in his own way. I repaid some of that by writing his DMOR in 2012–he was our founder–I was ashamed no one else had taken that action earlier.

[…] Article on “Charging Charlie”. The Special Forces Regiment has produced a number of ‘Legends’ over the past several decades of its history. One of them is Charlie Beckwith – probably best known as the commander of Delta Force. Two people, Irv Jacobs and Ben Rapaport, who knew Beckwith provide some personal anecdotes about him in an article published by the Sentinel (Dec 2025).https://www.specialforces78.com/a-legend-before-his-time-chargin-charlie-beckwith/ […]