Those Who Face Death: The Untold Story of Special Forces and the Iraqi Kurdish Resistance by Mark Grdovic

The Kurdish Woodstock & Operation Viking Hammer

By Mark Grdovic

An excerpt from Those Who Face Death: The Untold Story of Special Forces and the Iraqi Kurdish Resistance by Mark Grdovic, published by Copper Mountain Books, 08/15/2025 , pages 111-115 and 117-124.

Editor’s note: The mission was to engage Saddam’s troops in the North of Iraq during the 2003 invasion and prevent their use in the south against the advancing coalition. Operation Viking Hammer was to eliminate Ansar al-Islam, Islamic radicals who were enemies of the Peshmerga. This would free up troops to use against Saddam that would otherwise need to stay in place to keep Al Ansar at bay.

CHAPTER 11

THE KURDISH WOODSTOCK

To win any battle, you must fight as if you are already dead.

—Miyamoto Musashi

I got up just before sunrise, even though i’d been lying awake for far longer. I felt like I had the weight of the world on my mind, and I felt nauseous—partly from apprehension and partly from lack of sleep. I made a cup of coffee to warm my hands from the 45-degree cold night air and climbed the ladder to the roof of the PUK building headquarters on the outskirts of Sulaymaniyah where we had established our SOTF headquarters. I took ten minutes, admiring the mountains in the distance, centering myself, and preparing my mind for the day ahead.

I thought to myself how beautiful Sulaymaniyah was as its lights sparkled in the distance. The morning twilight highlighted the ring of mountains that surrounded the valley. The short-lived springtime grass transformed the area into a lush green landscape in beautiful contrast to the normal drab gray-brown rocky outcrops or snow-covered terrain. I watched a pack of roughly twenty feral dogs roam the outskirts of the PUK compound, training their squad of new puppies to announce any movement along the perimeter.

As I finished my coffee, I considered how much we had done to get to this moment. I was largely responsible for the plan up to this point. Had we done everything we could to prepare for what was ahead? What was the week ahead going to be like? It was surreal to think about the attack that we were about to conduct. I kept asking myself if we had done everything we could to prepare. Would the attack be successful? I couldn’t help but think of the expression I kept hearing the Kurds use: “inshallah,” if God wills it.

It was time to go. I came down from the roof, and we loaded up in vehicles for the two-hour drive to Halabja.

As we arrived in town, it was impressive to see so many Peshmerga assembled for one battle. Approximately 10,000 Kurdish forces were closing in on Halabja at this point, staging to conduct the attack. No doubt it put quite a burden on the infrastructure to support these people. They all still needed to eat and have water, so there was additional pressure from the logistics of it all—a growing momentum that served as a reminder that the attack needed to happen.

Halabja looked like a Kurdish version of Woodstock—there were Kurdish guys living in every little building and camping out on the lawns next to the buildings with small tarps. When evening came, they built hundreds of campfires with broken wooden trash to warm themselves and cook their last meals of whatever food they found. Everyone stared into the fires, hypnotized by the flames and lost in their own thoughts.

For the last few days, the teams had been conducting some harassment operations with mortars and crew-served weapons and close air support when we could get it. Fortunately, the day before the actual ground attack, we got word that we would finally be receiving the desperately needed lethal aid. The US government had acquired the former Soviet-style weapons and ammunition months ago in Eastern Europe and now the Air Force was finally going to deliver the goods. Not only was it a huge morale boost, but practically speaking, guys had been talking about going into this attack with only a few magazines, which is obviously not what you want to be carrying. Better late than never. The planes landed at the Suly West airfield and our convoy moved the aid by truck. As we distributed the lethal aid at Halabja, morale went sky-high. It was one step closer to where we wanted to be for the attack.

LTC Tovo meeting with Kok Mustafa and the prong commanders in Halabja. Note the blank side of his map on the Iranian side of the border.

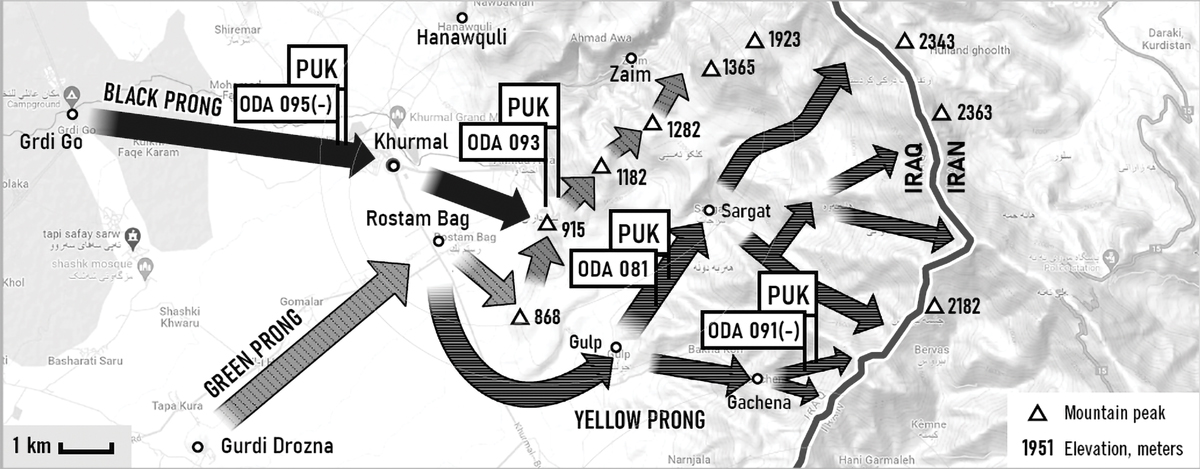

Soon after we arrived, we got bittersweet news. The IMKI was going to stay out of the fight, but the IGK was all in with Ansar. Unfortunately, our missile strike on the 21st had bad timing. One of the missiles struck their headquarters while they were holding a meeting to vote if they should join or separate from Ansar. We learned it also killed Saddam’s liaison officer to Ansar who was in attendance. The IGK alliance created a new problem for us. We had an entire new set of enemy positions on the north flank that we hadn’t planned for. A decision was made to split ODA 091 to support the Black Prong and the newly added Orange Prong on the northern flank. The team leader, CPT Eric Fellenz, remained with the Black Prong and Team Sergeant MSG Kevin Cleveland assumed responsibility for the Orange Prong.

Around midafternoon, word reached us in Halabja that Jalal Talabani was trying to broker a ceasefire between the PUK and Ansar with the IGK. When the PUK commanders on the ground heard the news, they did not receive it well. The time for talk had passed. Tovo headed back to Sulaymaniyah to explain why this was no longer an option. He was successful and returned a few hours later.

I was lying on the cold concrete floor, chilled and wide awake. It seemed no one else was sleeping around me, either. Somewhere around 0400 I could hear the first of several people start to stir and check their equipment again. Everybody knew what we were about to do. The air was calm, but the trepidation was palpable.

It felt like we were a medieval army attacking a walled city at first light. You could look out and see hundreds of small campfires. There was a strange calm that was distinctly different from the buzz that had been in the air all week as both sides had sporadic engagements with each other. Now, by contrast, it felt like the night brought a temporary period of uneasy calm over the entire region. It was unsettling.

Everything seemed to almost stop. Suddenly, the world had shrunk and the only things that mattered in that time were what was in your immediate vicinity. The three men sitting near you, quietly checking their gear, trying to eat something or sleep. There was no other world than this one, right now.

As I got myself together and collected my kit, I saw Bafel Talabani. I had developed a considerable amount of rapport with him by this point. I genuinely liked and respected him. He was a critical connector for us because of his English skills, but it’s a disservice to him to say he was just an interpreter. As the son of the leader of the PUK, he didn’t need to be here, but he was. His cousin Lahur was the same way. They seemed to always be at the most important place at the right time. They felt a responsibility to be a part of this fight. In fact, Bafel’s father wasn’t happy with him for allowing himself to be in the middle of the danger.

“Where are you going to be during the attack?” I asked. “I’ll be with 081,” he responded in his British accent.

I nodded. I knew that meant he’d be with the Yellow Prong. “How much ammo you got?” I asked.

“Four,” Bafel revealed. I had ten magazines for my M4, which did him no good as they were a different caliber of ammunition than his AK-47. I hated the fact that we had different rifles. My mind hastened back to the Cold War era when 10th Group used to maintain AK-47s for every Special Forces soldier, specifically for the unconventional warfare missions in Europe.

Prior to deploying, lessons from Afghanistan were starting to emerge where simply firing your M4 in a sea of AK-47s could put you at considerable risk because they sound very different. In the middle of a huge firefight with AK-47s, as soon as you hear an M4 fire, it’s instantly clear an American is shooting. The Taliban in Afghanistan quickly learned that killing an American also meant cutting off the close air support. Back at Fort Carson, I suggested we consider going in with AK-47s for these reasons. As we discussed this, Tovo thought we would really want our M4s because they had superior optics on them. I pointed out that we could put those optics on the AKs, but it didn’t matter because it wasn’t an option. In 1996, 10th Special Forces Group turned in all of their operational AK-47s because the prevailing belief was that they wouldn’t need them again.

MAJ George Thiebes (center) oversees the sand table brief for the attack on Ansar al-Islam.

Sometime prior to this, I had actually talked to Bafel about getting me an AK-47, because I would have preferred to not stand out as the lone American with an M4 amongst a group of Peshmerga.

When I asked, Bafel shot back, “I would love to give you an AK, but my government is just not that comfortable giving you that type of lethal aid. I’ll see if I can get you guys a bolt-action rifle or something.” I must give Bafel credit for his sarcastic wit and sense of humor. In all seriousness, he explained that giving me an AK-47 would mean literally taking one out of the hands of a Peshmerga.

Now as Bafel was getting ready to leave the PUK HQs in Halabja and join up with the Yellow Prong, I reached into my ammunition pouch and pulled out a grenade. “I feel bad that I can’t give you any ammunition, Bafel, but at least I can give you this. I hope you can give it back to me when this attack is done.” I could see the gratitude in his eyes as he accepted the grenade.

His reply spoke to this moment of friendship. “Thank you. Grenades might be a good thing to have,” he said simply.

“Good luck,” I replied, as he moved out to join 081.

By now, everyone was awake and moving around. The calm was over and we were now bracing for the storm. It was mechanical. Everyone knew what to do and was getting it done. At certain points in life, time either seems to speed up or slow down. This was a fast morning and time sped up and seemed to gain momentum, especially during the last hour. My thoughts raced through all the preparation we had been doing and everything that lay ahead of us. Now, there was simply nothing more I could do. It’s like studying for one of the biggest—if not the biggest—exams of your life. At a certain point, you have to close the book and hope like hell you’ve done enough preparation, because it’s about to start.

As I looked out across the field at thousands of Peshmerga, any anxiety I had now started to subside. I wasn’t sure if we would be able to do this in time to stop Saddam, but I was confident that Ansar’s reign of terror over Halabja was about to come to an end.

Map: the Green Yellow and Black Prongs

CHAPTER 12

OPERATION VIKING HAMMER

On difficult ground, press on.

On encircled ground, devise stratagems.

On death ground, fight.

—Sun Tzu

It was still dark as we made the five-minute drive up the dirt track to the top of Gurdi Drozna. The outpost atop the hill provided a bird’s-eye view to the start of the battle. I was standing alongside LTC Tovo, Kok Mustafa and the Charlie Company Commander, MAJ George Thiebes. We watched as the thousands of Peshmerga in long convoys of pickup trucks jockeyed for positions along the narrow roads. A few dump trucks had been converted into makeshift armored personnel carriers with sandbags and steel plates. Toward the front of each prong, a group of approximately one hundred men assembled. These would be the spearheads for each of the prongs.

At 0600 exactly, the single D-30 artillery piece fired a round, signaling the start of the attack.

The visit to Gurdi Drozna to see the Ansar al Islam defenses.

THE GREEN AND YELLOW PRONGS

The objectives along the Green Prong’s axis of advance included hills 868, 915, 1182, 1285 and 1365. The hills on the military maps were named based on the elevation of their peaks, depicted in meters above sea level. The Green Prong started their attack toward the first objective, hill 868. The sun was just starting to rise as the prong started taking some sporadic machine gun fire from the first line of enemy forces. The PUK responded with a volley from their 107 mm Katusha rockets, 106 recoilless rifles, 23 mm anti-aircraft gun, and 82 mm mortars. Within ten minutes the first aircraft was overhead. A Navy

F-14 dropped a single bomb on a position blocking the Green Prong and, in an instant, the fighting position was completely destroyed.

The other defenders higher up the valley had full view of the display before them, like fans watching a sporting event in a stadium. In the distance a B-52 dropped a line of bombs along the length of one of the higher ridgelines. I couldn’t help but wonder, now having seen firsthand what was coming, if their extremist fervor was starting to waver as the reality of the situation started to sink in.

At the base of hill 868, the prong’s commander, Kok Abdulla, remained crouched behind a rock wall with one hundred Peshmerga and ODA 093. As the fires shifted to hilltop 915, a B-52 dropped its ordnance on the next hilltop behind that, hill 1182. Kok Abdulla blew his whistle and the assault force of Peshmerga and Special Forces, following their commander, went over the wall and started the attack.

The Yellow Prong, with ODAs 081 and 091, was already moving about two kilometers to the southeast of the Green Prong. The Yellow Prong’s objective was to seize the town of Gulp, which sat on a crossroads to the entrance of two valleys—one of which led to Sargat and the other to Gochina. ODA 081 and a contingent of Peshmerga were to seize Sargat and the chemical/biological testing facility and ODA 091 with their Peshmerga would take Gochina.

The Green Prong’s advance and subsequent objectives would take them along the north side of the valley that oversaw the Yellow Prong’s advance toward Sargat. This would allow the two prongs to support each other with fires. SSG Chris Crum was an engineer and demolitions sergeant from ODA 081. He was one of three men who would move with ODA 093 on the Green Prong to help coordinate their efforts. In addition to the array of equipment the ODA had with them, Crum also had his M82 Barrett sniper rifle. The rifle fired .50-caliber match grade, armor piercing, explosive incendiary rounds. The rounds were originally intended for targeting vehicles and helicopters. The round explodes after penetrating a target, hitting the occupants with burning shrapnel as well as potentially igniting any fuel or ammunition.

With the thirty-pound rifle in hand, SSG Crum followed the Peshmerga. In addition to the rifle, he carried seventy rounds, his radio, a couple grenades, a pistol, and some water. Combined with his body armor he was carrying approximately eighty pounds of gear. The Peshmerga, by comparison, had no body armor, carried relatively little ammunition, and had no radios or water. He knew keeping up with them in the steep terrain would be a challenge.

Within minutes, the Peshmerga closed the distance and were flooding over their position, engaging any enemy who might have survived the air strike. As they advanced up the hill, a young Peshmerga about twenty-five meters away from the Americans exploded. They were advancing across a minefield and the craters from the air strikes slowed their movement. On the top of the hill, the Peshmerga swiftly directed the team members along a path between the small rock piles denoting buried mines. There were hundreds of them.

Looking through the scope on his rifle, Crum could see the Yellow Prong below had already cleared Gulp and was pressing up the valley. The ground around him was littered with dead Ansar fighters. There was little time to take stock as they had to push on to hill 915 to maintain contact with the Yellow Prong’s advance. As the group crested the top of hill 915, the convoy from the Green Prong had driven up to meet them. After a quick resupply of ammunition and water, the element decided, in the interest of time, to tactically drive toward hill 1182 until they made contact.

In the valley below, the Yellow Prong was met with a hail of machine gun fire from a small hill near the entrance to the village of Gulp. The Peshmerga instinctively started running toward the fire. Suddenly the charge was interrupted by the sound of a low-flying jet breaking the sound barrier. The group stopped charging to look up and see the aircraft.

When a fighter rips through the air, the sound is more than loud— it’s violent. Imagine the sound of tearing paper, only thousands of times louder. You can also tell when a fighter spots its intended target. The way it flies distinctly changes to something much more deliberate and aggressive. Watching the aircraft roaring overhead, it felt like we had brought mechanical dragons with us and suddenly unleashed them on the enemy.

As the hilltop exploded and the machine gun went silent, the screaming Peshmerga charged forward along the road into the village. One of the NCOs from ODA 081, SSG Mark Giaconia, was following the Peshmerga assault. His mind made a note of the gunfire to his far left on the high ground and he could hear the distinct sounds of Chris Crum’s Barrett sniper rifle. He wondered how his team was holding up, but then his mind quickly returned to his own situation as he noted the severed body parts of enemy fighters along the road.

Members of ODA 081 and 093 on the Green Prong during operation VIKING HAMMER. SSG Chris Crum takes aim with his Barrett 50 cal. Sniper rifle (lower right).

As the Yellow Prong entered Gulp and moved among the multitude of buildings, they came upon a mosque in the village center. Several dead fighters lay in twisted positions around the perimeter and inside the building. Among the dead were piles of leaflets in Arabic. On the cover were propaganda images: burning American and British flags and a picture of the World Trade Center collapsing. As the group inspected the mosque, another convoy of Peshmerga from the Yellow Prong, along with ODA 091, broke off to the right and continued toward the town of Gochina, roughly two kilometers from the Iranian border.

The Green Prong advanced to just below the crest of hill 1182. Despite the earlier air strikes, the top was still manned by a handful of fighters. The Peshmerga engaged the positions with their 106 mm recoilless rifle and heavy machine guns, causing the fighters to take cover behind a rock formation. SSG Crum spotted the group of fighters with his Barrett sniper rifle and estimated their range as 1400 meters. His first few rounds hit a few feet to the right. The impact caused the rocks to fragment, trigging the fighters to move farther to the backside of the hill.

As the Yellow Prong advanced up the road in the valley toward Sargat, they came under intense fire from the high ground on their left. The team sergeant spotted the fighters and directed the team to fire their M240 machine gun and MK-19 at the positions. SSG Giaconia was carrying an M21 sniper rifle. Looking through his scope, he could make out the bearded fighters taking cover on the hilltop. He could distinctly see them engaging the Green Prong. He inhaled, then slowly exhaled as he squeezed the trigger. The round struck its target and the fighter fell to the ground.

From hill 1182, Crum recognized the sounds of the MK-19 and realized it was 081 and the Yellow Prong. They were both engaging the same group of fighters from two sides. As the fighters took cover from the MK-19 rounds, Crum sighted in on two of the Ansar fighters. Making the adjustment from his last engagements, he fired one round and then another. This time he hit both targets. Crum and his teammates from the Yellow Prong continued to suppress the remaining enemy as the Peshmerga moved closer for their final assault. After they cleared the final positions, the Peshmerga secured hill 1182.

Continuing toward Sargat, the Yellow Prong had to advance through a curve in the valley that took them out of supporting view from the Green Prong. After the previous engagement, SSG Giaconia started to grow concerned that the columns were beginning to get separated from each other. He had lost contact with the other two elements from his ODA, one under the control of CPT Brian Rauen and the other under the team sergeant’s control. He was unable to reach anyone on the radio. Just then, as Sargat came into view, the column came under intense fire from their front. Somewhat channelized by the terrain, the members of the prong had little terrain that provided suitable cover.

He quickly took cover behind a small rock wall. The fire was significantly more intense than anything he had previously experienced. The sheer volume of bullets flying back and forth looked like a horizontal rainstorm. SSG Giaconia, completely exhausted from the twelve hours of fighting, was feeling a dark wave come over him. Despite all his previous brushes with death, this was the first moment when he truly felt like they might not survive. Then CPT Rauen, the team leader of ODA 081, somehow sprinted through the hail of bullets, dodging gunfire to dive next to his guys behind the wall. CPT Rauen was attempting to rally his team, telling them they had to get up, get moving, and press forward to some cover about twenty meters off the road.

Although the situation was incredibly dire, Rauen’s surprising calm and positive demeanor triggered something in Giaconia. It reenergized his resolve that they were going to survive this fight, or at least go out fighting. Rauen again took off running amidst the hail of gunfire to his next position. Giaconia realized immediately the captain had dropped his map. A moment later, Rauen returned, running through the fire again. Over the cacophony of gunfire, Giaconia shouted “You’re going to get killed! I would have brought it to you.”

CPT Rauen shrugged off his concern and responded, “I needed my map.”

Giaconia and the Peshmerga with him continued to take fire as they darted from one position to the next, eventually low crawling to get to their final covered position. They were collocated with CPT Rauen, Bafel Talibani, and Randy from the CIA. Bafel was on the satellite phone with his father and Randy joked this would be the last time he would accompany Green Berets on an operation. The valley echoed with the sounds of a heavy machine gun firing from a bunker on the high ground, most likely a Soviet-era 12.7 or 14.5 mm Dshka machine gun.

The Untold Story of Special Forces and the Iraqi Kurdish Resistance | Mark Grdovic

The Team House hosts Jack Murphy and Dave Parke have a conversation with Mark Grdovic, who recounts his experiences as a member of the 10th Special Forces Group during the Iraq War, particularly focusing on their operations with Kurdish forces.

The Team House is a weekly livestream/podcast focusing on U.S. Special Operations, intelligence, and military experiences. Episodes are available on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and YouTube, and other major podcast platforms.

They realized if they didn’t destroy the gun, it was going to destroy them. They hatched a plan to run the couple hundred meters back to their pickup trucks, drive the trucks to the base of a piece of high ground and then carry the M2 .50-caliber machine gun, tripod, and ammunition up the hill to engage the enemy gun. The team’s medic, SSG Ken Gilmore, and communications sergeant, SSG Blake Kramer, joined Giaconia and made the mad dash toward the trucks under fire. As they ran with tracers moving past them in both directions, it dawned on the NCOs there was a fair likelihood of accidentally being shot by a confused or frightened Kurd. They started shouting in hopes of not surprising the Peshmerga by running toward them.

As they reached the trucks, the group loaded up and prepared to drive closer to the base of a nearby high ground. As they started forward, a burst of fire hit the windshield and exited the passenger’s window without hitting anyone in the cab. They sped 300 meters to the base of the hill and dismounted. With their weapons slung on their backs, Kramer lifted the entire eighty-pound gun and the attached sixty-pound tripod and hefted the entire assembly over his shoulder. Gilmore and Giaconia grabbed as many ammo cans as they could carry and directed half a dozen Kurds to do the same.

Fighting the forty-five-degree rock scree and mud slope, the group clambered 300 meters up the hill. Exhausted and enraged, they dropped their heavy loads to the ground. Instantly, the three-man team went to work. One man straightened the tripod and adjusted the gun in its cradle while another scanned for the target and the third opened the ammo cans and placed a belt into the feed tray. Within a minute Kramer was plunging effective fire onto the enemy bunker 600 meters away. Through his M21 sniper rifle scope, Giaconia watched as bullet after bullet fired from their .50-cal passed through the bunker where the enemy fire was originating. He watched as the bullets entered the building and passed out onto the other side. The sound of their gun echoed across the valley, drawing the attention of the Ansar fighters, who understood the threat it now posed. Despite the barrage of enemy small arms, the three NCOs wisely sank as low as possible and continued to pour fire into the bunker. After 200 rounds, the enemy gun was finally silent. From their vantage point, they now watched as the Peshmerga assault force flooded over the enemy defenses and arrived at the Sargat facility.

As they made their way to back to Sargat to link up with the rest of the team, one of the Kurds named Wahab stopped them. He had been following along during the firefight trying to catch up to the Americans. Wahab presented them with what can only be described as a charcuterie plate of meat and cheese. Mark looked at him in utter disbelief. “What is this?”

“I figured you might be hungry,” Wahab offered. “I know Brian [CPT Rauen] likes soda, so I brought him a soda, too.”

The soda tasted especially sweet as the group took a short and much-needed break to have some lunch and regroup. They sat a few feet from the facility, which by now was a large pile of rubble with a fence around it. Gunfire several hundred meters away reminded them that fighting was still underway. The trucks that had functioned as personnel carriers earlier were now ambulances. As the trucks stopped, a steady stream of blood flowed off the tailgate and pooled in the road. The team’s medics looked at the wounded and did what they could. A casualty collection point had been established near the first objectives of the day and was manned by the battalion surgeon, MAJ Rick Ong, and his surgical team. They dealt with dozens of wounded, some walking miles with gunshot wounds to reach the collection point.

As the trucks departed, the team did a cursory search of the facility. The team leader decided to delay the facility inspection for the exploitation team that would come in the following morning. Hundreds of charred and mutilated enemy bodies lay all around the facility.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

LTC (RET) Mark Grdovic served with the US Army for over 23 years, including 19 years as a Special Forces officer. He served with the 10th Special Forces Group, the US Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center, US Army Special Operations Command (USASOC), Special Operations Command Central (SOCCENT) and the White House Military Office (WHMO). His experience includes multiple deployments to Bosnia, Iraq, and Afghanistan and crisis response operations in Europe and Africa. Since retirement in 2012, he has served as a defense consultant and contractor supporting USSOCOM in a variety of capacities. LTC (Ret.) Grdovic holds a Master’s degree in National Defense Studies from King’s College London. He lives in Florida with his wife, Gretchen.

Visit www.markgrdovic.com for additional details LTC Grdovic and his book Those Who Face Death, to read additional reviews, to view bonus material from the book, to request a speaking engagement, or to order his book.

LTC (Ret.) Mark Grdovic shared stories about his time in Iraq during Task Force Viking at the 2022 Special Forces Association Convention in Colorado Springs.

[…] At this link, Mark shares with us Chapters 11 and 12, from the personal and immediate lead-up to Operation Viking Hammer to eliminate Ansar al-Islam, and the exciting beginning parts of the battle. […]