STARS:

Surface to Air Recovery System

By Colonel John Gargus (USAF, Retired)

Originally published in the April 2019 Sentinel

Surface to air recovery system (STARS) was the most exciting operational capability of the early C-130 Combat Talon aircraft. Each one of the eleven crew members had a role in this unusual event. Regretfully, it was never employed during the Vietnam War for its designed purpose to recover stranded personnel from otherwise inaccessible hostile environment. Live personnel recoveries were staged only for the VIPs and air crews that were most likely to end up stranded deep inside of enemy territory.

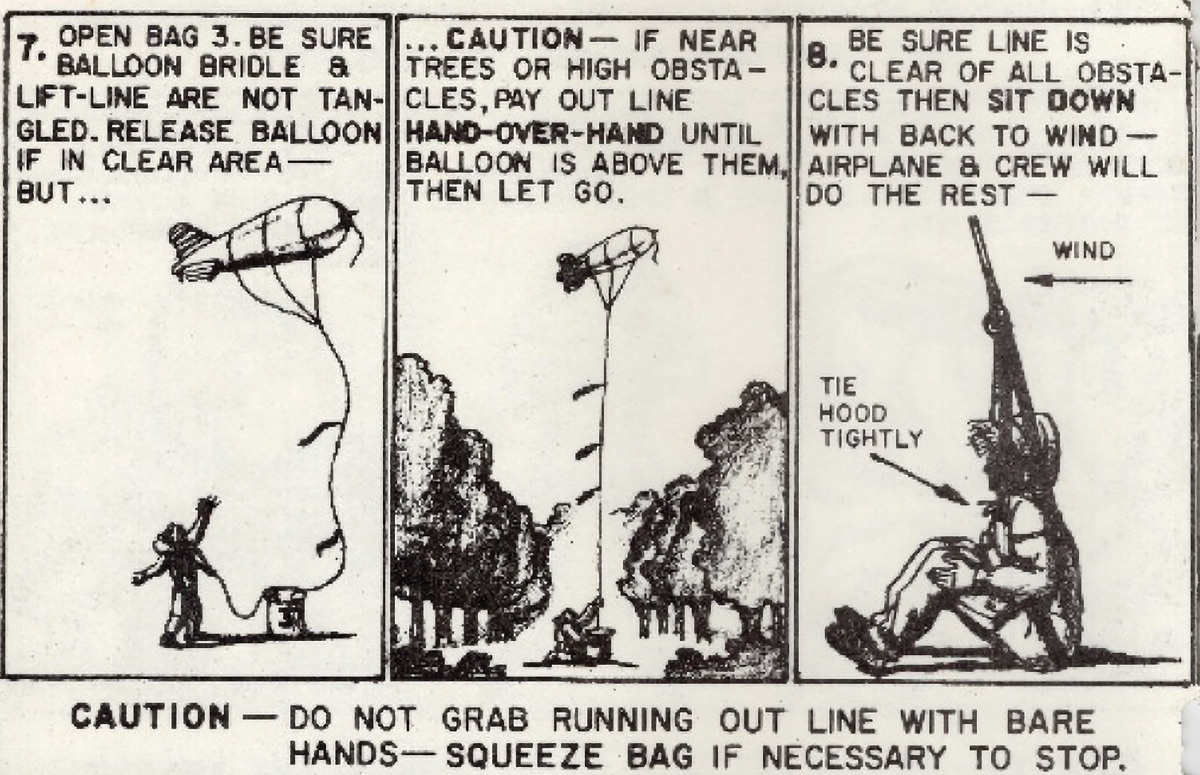

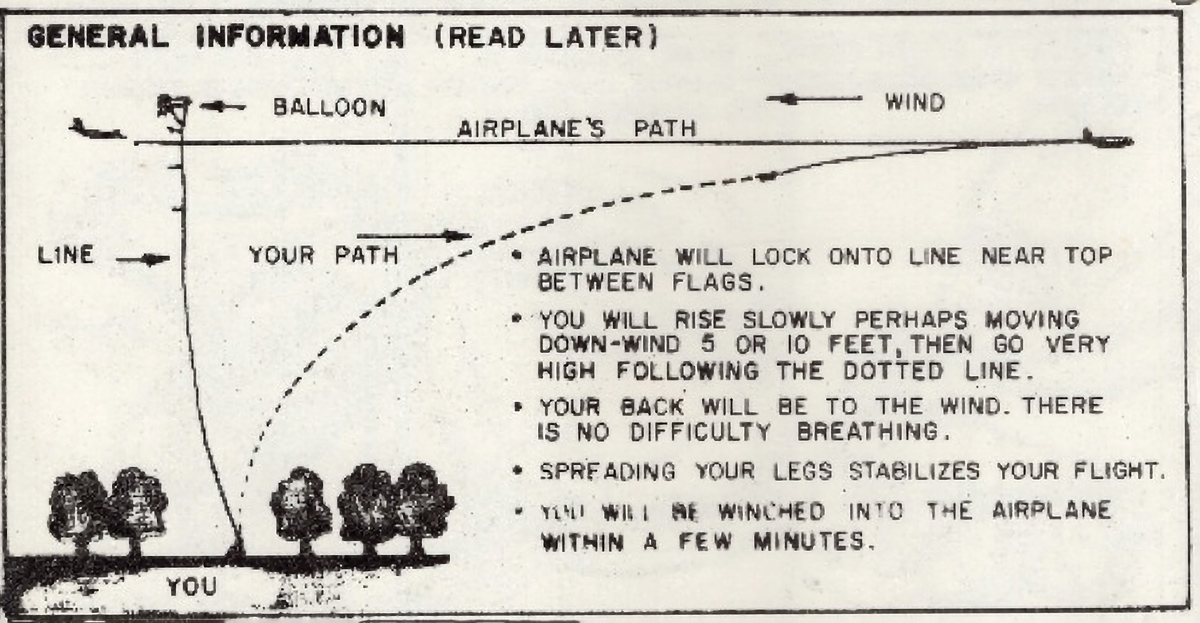

Ideally, a Combat Talon would air drop a one or a two man Fulton recovery kit to a survivor and then 20 minutes later return to intercept a 500 foot long lift-line for a ground to air extraction. This time was believed to be sufficient for an able bodied survivor to unpack the kit and follow enclosed instructions to don the special harnessed suit connected to an inflatable balloon by a 500 foot long nylon braided lift-line. The kit’s helium containing canister was included for that purpose. Fully inflated balloon would hoist the lift-line to the level of the rescuing aircraft and the survivor was instructed to sit down facing into the wind and wait for an exhilarating lift off.

A page from the Skyhook kit instructions on how to assemble the Skyhook for recovery. Photo courtesy of Stray Goose International (SGI)

Meanwhile, the Combat Talon’s crewmembers would make their own preparations.

Two loadmasters would secure themselves with restraining harnesses on the lowered ramp ready to secure the lift-line to the equipment that will bring the survivor inside of their aircraft.

The second flight engineer would become the winch operator who will control the reel in of the lift-line with the trailing survivor suspended at its end. Behind the flight engineer is the third pilot who will serve as the safety officer. He will monitor the movements of the ramp crew, interpret their hand signal communications and relay the recovery progress to the cockpit crew through the intercom.

Loadmasters do not wear headsets because the intercom cables could restrict their movements on the ramp.

During demonstration pick-ups the electronic warfare officer and radio operator observe the operation from their crew positions at the bulkhead of the cabin because they have no assigned duties. However, on pick-ups inside of hostile air space they would play key roles in keeping the aircraft out of harm’s way.

Then the electronic warfare officer would monitor transmissions from enemy radars and provide warnings of impending attacks and the radio operator would assist him and maintain contact with a controlling ground based or airborne command post.

Up in the cockpit, the map reading navigator would don a restraining harness and open the overhead escape hatch through which he will have to retrieve the trailing upper portion of the lift-line.

The radar navigator would determine the wind direction and velocity and guide the aircraft for a head wind approach to the survivor and his already lift-line tethered balloon.

The two pilots with the flight engineer between them would begin to strain their eyes, trying to locate the deployed balloon and the three red flags on the lift-line just below it. For nighttime pick-ups there would be three pulsating strobe lights spaced in the same lift-line location.

Once spotted, the flags, or the strobe lights, must be perpendicular to the horizon to ensure that the aircraft is headed upwind. Consequently, if the flag alignment stretches at an angle from one o’clock to seven o’clock position, the aircraft must make a track correction to the right until the flags are aligned from twelve to six o’ clock position.

Once that is done, the intercept flying pilot aims for the middle flag and ensures that the lift-line gets engaged between the 24 foot span of extended “V” shaped yokes for a safe slide into the nose mounted locking mechanism.

In case of a miss, the lift line gets cut by sharp blades imbedded in the cables that are stretched between the aircraft’s nose and its wing tips. This prevents the lift-line getting wound up around the spinning propellers.

Also included in the Skyhook kit instructions, this diagram illustrates the aircraft snagging the line and taking the man in tow. Photo courtesy of Stray Goose International (SGI)

The first sensation the survivor experiences is a gentle lift one feels on an upward curve of a playground swing. This wink of an eye moment is followed by a rapid vertical acceleration that measures less in “G” forces than the opening shock of a parachute. This vertical ascent can clear a 30 foot tree 5-10 feet behind the sitting survivor. Then the vertical lift transits in to a rapid upward curved path that propels the survivor well above the aircraft’s flight level. It is then followed by a downward fall along a diminishing sine wave curve until the survivor’s path gets stabilized behind the aircraft at its flight level. The first downward path along this sine wave curve frightens the survivor because its descending movement increases his body’s velocity and diminishes the forward pull on the line, giving him a sensation that he is freefalling and is no longer connected to the lift-line.

The sudden jerk on the lift-line ruptures the balloon and the loose end of the line slaps down on top of the aircraft’s fuselage. The map reading navigator has to retrieve it into the aircraft by sticking out the upper part of his body through the escape hatch into the 135 mile slips stream. He has a tied down pole with a hook to help him to pull the line that ends up draped on either side of the fuselage into the cockpit for clean-up. He has to remove the remnants of any flags or glass strobe lights from the line and cut off the hardened pig tail of the line to prevent them from jamming in the nose locking device. This allows the loadmasters an easy pull through of the lift-line to the rear ramp of the aircraft.

Meanwhile, the loadmasters either kneel, or lie down, on the floor of the ramp and try to snatch the lift-line trailing behind the aircraft with a special bomb shaped fish hook. They pull the line inside and secure it in two places on the ramp. Then they wait for a signal from the safety officer that they can pull the top of the lift-line out of the cockpit through the released nose locking device. Once this is done, they lock the tail of the line to the winch and raise an “A” frame support for a pulley that elevates the lift line from the floor to a shoulder height level. This allows the pulled in survivor to arrive at the ramp in a stand up position. The flight engineer then operates the winch that winds up the lift-line and reels in the survivor for a joyous welcome on board event.

About the Author:

John Gargus was born in Czechoslovakia from where he escaped at the age of fifteen when the Communists pulled the country behind the Iron Curtain. He was commissioned through AFROTC in 1956 and made the USAF his career. He served in the Military Airlift Command as a navigator, then as an instructor in AFROTC.

He went to Vietnam as a member of Special Operations and served in that field of operations for seven years in various units at home and in Europe. He participated in the air operations planning for the Son Tay POW rescue and then flew as the lead navigator of one of the MC-130s that led the raiders to Son Tay, for which he was awarded the Silver Star.

His non-flying assignments included Deputy Base Command at Zaragoza Air Base in Spain and at Hurlburt Field in Florida and a tour as Assistant Commandant of the Defense Language Institute in Monterey, California.

He retired in 1983 after serving as the Chief of USAF’s Mission to Colombia, having accrued more than 6,100 flight hours, including 381 combat hours in Southeast Asia. In 2003 he was inducted into the Air Commando Hall of Fame. He has authored two books, The Son Tay Raid: American POWs in Vietnam Were Not Forgotten, published in 2007, and Combat Talons in Vietnam: Recovering a Covert Special Ops Crew, published in 2017. He has been married to Anita since 1958. The Garguses have one son and three daughters.

Leave A Comment