An Excerpt from

Across The Fence: The Secret War In Vietnam

Four Bullets In His Boots

Members of ST Virginia taking a photo break during training in Phu Long, outside FOB 1 in January 1969. Standing in back from left, Doug “The Frenchman” LeTourneau, an indig team member and newly appointed One-Zero, Gunther Wald, who served in the Marine Corps before joining Special Forces and an unidentified team member. Kneeling are several indig team members, including Hoahn, interpreter, last on right. (Photo courtesy of Doug LeTourneau)

By John Stryker Meyer

From Across the Fence: The Secret War In Vietnam, Expanded Edition; SOG Publishing, April 21, 2011; Chapter Eight, pages 155-175; used with permission.

A few days after returning from the Echo 4 target, I talked to Spider Parks and Pat Watkins about the many changes that were swirling around the American component of ST Idaho and whether or not I was ready to be a One-Zero. Spider provided brotherly advice and reminded me that I had been on the team more than four months and that he and Wolken had trained ST Idaho hard after the old ST Idaho team disappeared in May. “Talk to Sau and Hiep. See what they say,” he advised.

I walked over to the indig team room and talked with Sau and Hiep. After a few more jokes from Hiep about my feet being too big and me being too tall a target, he said that he and Sau thought I would be okay as a One-Zero. Besides, he added, he and Sau didn’t want any strangers taking over our team, like what had happened to ST Alabama. Hiep ended the brief chat by telling me that I might not be the brightest American in camp but I did okay calling in air strikes.

I went back to Spider, and he had that “I-know-what-happened” grin on his face. We went to the S-3 shop and made it official: I would be the ST Idaho One-Zero. I was pleased that Spider, Sau and Hiep had faith in me. But, at the same time, the invisible weight of being a One-Zero landed on me mentally—their safety now rested squarely on my shoulders. There was no celebration. We simply went about our business. I asked S-3 about replacements. The sergeant said there were a few new SF troops slated to arrive at FOB 1 any day. With that, I packed up the team and headed to the range for live-fire drills.

While we trained in Phu Bai, the replacements arrived in Da Nang. Among the newly-minted Special Forces soldiers were Douglas L. LeTourneau, a skinny, 135-pound California cowboy, John Shore, a blond-haired, slightly overweight, baby-faced kid from Georgia, and Frank McCloskey, a tough, combat-hardened veteran of the 101st Airborne Division. McCloskey arrived sporting seepage from a wound in the back of his head.

This trio of Green Berets had completed their Special Forces in-country training program in Nha Trang, the 5th Special Forces Group Headquarters. When a sergeant in Nha Trang asked for Special Forces soldiers to volunteer for a “secret project” they raised their hands. In short order they were flown to FOB 4, in the northern sector of South Vietnam—I Corps. Upon reporting in, they were told camp commander Col. Jack Warren would brief them in the morning on the C&C mission in Southeast Asia.

Finally, after more than a year of training for LeTourneau, the game was on. How much better could this get? It seems all his life he’d been preparing for this moment, from riding rodeo broncs and breaking nearly every bone in his body to wrangling animals for television shows like Daktari and Cowboy in Africa, starring Chuck Connors, LeTourneau knew a little bit about taking a calculated risk. And after he had gotten his hands on Robin Moore’s book The Green Berets he knew this was for him. Guerilla warfare? Check. Counterinsurgency training? Check. Unconventional warfare? Check. LeTourneau couldn’t wait to write his own story that he could someday share with his dad, a WWII B-17 pilot and former POW.

Nothing, however, could have prepared him for the sight that greeted him as he entered the transient barracks. There, etched into the concrete floor, and forever in his memory, was the charred outline of a man’s body, a grisly reminder of the 23 August 1968 attack on FOB 4. That fateful evening, North Vietnamese sappers and Viet Cong operatives killed 18 Green Berets in a carefully executed sneak attack.

The deadly side of guerrilla warfare was brought home to him right there. He was in a war zone. The enemy didn’t play by any set rules. It was an unsettling evening.

The next morning after breakfast, the trio walked over to S-3 and chose their codenames. LeTourneau, McCloskey, and Shore now became “The Frenchman,” “Namu,” and “Bubba”—names that would stick with them far beyond their tours of duty in Vietnam.

Because S-3 was temporarily located in the headquarters section of FOB 4 since the attack it was a quick shuffle into the briefing room with everyone else. An intense, short, black-haired man wearing pajamas, slippers and a bathrobe walked in smoking a cigarette. Before a word was spoken, Col. Warren abruptly pulled a white sheet off a large map with a flourish, tossed it aside, and announced, “Welcome to C&C, men.”

Turning to the large map that had black-tape, boxed target designators on it in Laos, the DMZ and North Vietnam, he continued. “This is what you volunteered for. This is why this is a top-secret project. If anybody asks, the president can say we have no men stationed in the AO. That’s why you’ll wear sterile fatigues and carry no form of identification of any kind on your missions. That’s why you agreed not to talk to anyone about this operation for at least 20 years. Our intel reports land in the White House. Any questions?”

Not waiting for a response, Warren continued to explain the difference between spike teams and hatchet force elements, where the different FOBs were located, how FOB 3 at Khe Sanh was closed after the siege earlier in the year, and how Major Clyde Sincere, Jr. had opened a site at Mai Loc now designated FOB 3.

Following an update on intelligence reports in the respective Areas of Operations, Col. Warren asked if anyone had any questions. LeTourneau raised his hand. “Where do you need help, sir?”

“We need men at FOB 1. We lost a One-Zero on October fifth and some of the First Special Forces TDY (temporary duty teams) troops from Okinawa are returning back to the island.”

LeTourneau turned to Shore and McCloskey and asked, “How about it? FOB 1?” Shore nodded in the affirmative.

McCloskey said, “No. I think I’ll stay here.”

LeTourneau turned back to Warren and said, “We’ll go,” nodding toward Shore, surprised at McCloskey’s response.

From left, Don Wolken and John McGovern take off in a Kingbee heading to Quang“ Tri. Although they are smiling here, both had volunteer for a special mission. (Photo courtesy of Stephen Bayliss)

Without missing a beat, Warren told the remainder of the SF troops in the room that he’d be right back. He turned to LeTourneau and Shore and said, “Follow me,” as he headed out of the briefing room and into the S-3 Operations Center. He told the Center staff to get a Kingbee to FOB 4 in an hour to transport LeTourneau and Shore to FOB 1 ASAP. Next he headed to S-1 and told the clerk that the newbies were to be processed and cleared to go to Phu Bai.

An hour later, PFC LeTourneau and Spec. 4 Shore were in a Kingbee heading north over the Hai Van Pass that crossed the rugged Troung Son Mountain. As they flew parallel to Highway 1, the door gunner nodded to LeTourneau and Shore, indicating they should sit in the doorway that was on the right side of the chopper, thus setting them up for the typical newbie welcome to FOB 1. Unaware, they sat on the floor and enjoyed the ride, dangling their feet outside as the Kingbee pilot did some nap-of-the-earth flying.

After they passed the Hue/Phu Bai Airport on the eastern side of Highway 1 in Phu Bai, the Kingbee pilot abruptly rolled the chopper on its right side, providing LeTourneau and Shore with a heart-stopping look at the ground. Both leaped to grab something that was attached to the aircraft, anything that didn’t move as the crew quietly laughed at their expense.

When they landed, the rookies quickly jumped off the chopper, grabbed their gear made their way across Highway 1 to the long road that led to the command center. A truck carrying a recon team drove past the jittery pair, heading to the landing zone.

When they finally reached the S-3 shop, it was a beehive of activity. They were told to step outside and that someone would take them to their billets once things calmed down. The departing recon team had a Brightlight mission. That meant a team on the ground was in trouble. LeTourneau and Shore were not a priority.

As they stood outside, Pat Watkins walked up and introduced himself. He then promptly asked LeTourneau if he had been demoted to PFC before shipping out for South Vietnam. Watkins had done his homework. Before LeTourneau and Shore landed at FOB 1, Watkins had gone into S-1 to learn about the new men being sent to Phu Bai. The Frenchman was listed as a PFC and his MOS (Military Occupational Specialty) was listed as weapons. At that time, in Special Forces, no one below the rank of E-5 received that SF MOS when going through Special Forces Training Group. When he saw LeTourneau’s MOS and rank, he thought either LeTourneau was a badass who’d been demoted or he was lying.

LeTourneau explained that when he went through Training Group, he had requested the weapons MOS, pointing out that he had joined SF to go to ‘Nam and that he wanted to go as a weapons man. Somehow he convinced the review board to allow a private E-2 to go through that training, thus setting a new precedent. He was one of, if not the first, E-2s to get that training. On that day, every E-2 that came after LeTourneau alphabetically had the option to elect for SF weapons training.

SFC John McGovern walked by and Watkins introduced LeTourneau to the veteran SF trooper. McGovern had run several missions with the Hatchet Force before being transferred to Recon Company, where he eventually became the One-Zero of ST Virginia. By October, McGovern was one of the senior enlisted men in camp. All of the recon men respected him due to his experience running missions and his ability to work with indig troops. In short, McGovern epitomized the quiet professional, the experienced combat-veteran Green Beret who quietly performed his missions without pomp and circumstance.

Watkins told McGovern about LeTourneau’s MOS and that he wanted to run recon. McGovern said ST Virginia could use a weapons trained troop. He said he was getting short in country and that he was going to be transferred to the S-2 shed for his remaining time during this tour of duty in South Vietnam.

“Let me introduce you to the new One-Zero of ST Virginia Spec 5 Childress,” McGovern said. Childress had run several missions and McGovern described him as a good man. McGovern explained that the recon teams needed SF-qualified men to replenish the recon team ranks. Back in May, there were 30 recon teams in camp. By mid-October, only a few teams were fully operational. “We’ve lost some good men in recent months.”

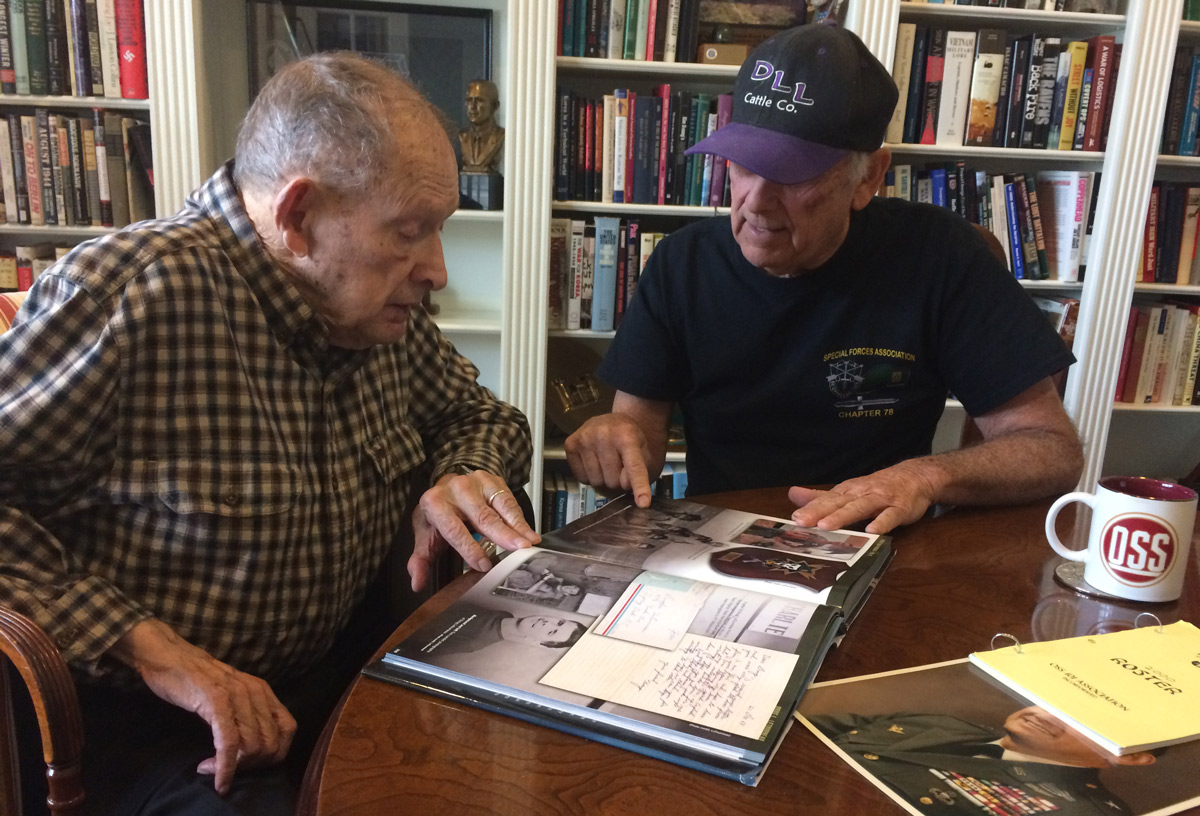

Doug LeTourneau, left, and,John Meyer, at right, at SFA Chapter 78’s July 2019 Chapter meeting. (Photo courtesy of John Stryker Meyer)

Meanwhile, Watkins told Shore ST Idaho had an opening because the One-Zero had transferred to flying Covey.

Within 24 hours, LeTourneau and Shore were on recon teams at FOB 1 and they immediately began training: immediate reaction drills, weapons and explosives training, reviewing team SOPs, practicing helicopter extractions on strings. and practicing wire taps.

As October yielded to November, many of the members of the two recon teams began to build a rapport because they were doing so much training together on the Phu Bai range. In addition, LeTourneau and Shore also quickly learned that the veteran indigenous personnel on their teams were highly skilled and fearless warriors.

One night, while LeTourneau was recording a verbal message for his parents on his portable cassette player, Lap—the young point man on ST Virginia—came into his room and spoke into the recorder: “I want to tell you, parents of Private LeTourneau, not to worry about him. We respect him and I’ll keep an eye out for him. And, don’t worry; if an enemy shoots at him, I’ll catch the bullets with my body. I’ll protect your son. Thank you for sending him to Vietnam. He’s a good soldier.”

A few days before Thanksgiving, ST Virginia’s One-Zero Childress announced that an operation order had come down from S-3. The team had a mission in the western section of the DMZ. Childress told them that he was going to fly a VR of the target area before the team launched for the mission. He also introduced a young lieutenant who would be assigned to ST Virginia for the mission. “We need bodies and we’re glad the lieutenant volunteered to join us,” he told the team.

After the team meeting, Childress told LeTourneau to help the officer obtain any gear and equipment needed for the mission. When Childress left to fly the visual reconnaissance, LeTourneau and the lieutenant walked over to the supply building, gathered all of the appropriate gear and assembled it so the officer would be comfortable under the weight of his web gear and rucksack.

Afterward, LeTourneau ran into McGovern and mentioned that ST Virginia finally had a mission, but he didn’t have a CAR-15—the preferred weapon among most recon men at FOB 1—even though the lieutenant had somehow obtained one. Since he was only a PFC, LeTourneau didn’t want to ruffle any feathers.

The quiet-spoken McGovern gave him a wry, half smile and said, “We can’t have that. You need to have a CAR-15 for your first mission. Follow me.”

The duo walked over to McGovern’s room. He opened his locker and pulled out a clean CAR-15 and handed it to LeTourneau. “This is a special CAR-15,” he said. “According to official Army records, this CAR-15 was written off as a combat loss at FOB 3 Khe Sanh, meaning as far as the Army’s concerned this weapon doesn’t exist. Some day, after a successful tour of duty in Vietnam, if you’re so inclined, you can take this baby home with you because it doesn’t exist. But, as you can see it does and it’s a sweet weapon. It never failed me. And I know that since you’re a weapons man, you’ll take good care of it.”

Up to this point, LeTourneau had used an M-16 for all of his training. Now, with his CAR-15 he was ready to take on the world.

That opportunity arrived on Thanksgiving Day 1968. After the weather cleared at the Quang Tri Launch Site, ST Virginia boarded the Kingbees and headed west to the target area, with three American and four South Vietnamese team members: Lap, the 17-year-old hard-core point man who had run many missions; Hoanh, the interpreter; Cho, the M-79 operator; and Khanh “Cowboy” Doan , who had fought valiantly beside Lynne M. Black, Jr. with ST Alabama.

As the second Sikorsky churned westward, the 135-pound LeTourneau went through a mental checklist of everything that he was carrying: McGovern’s CAR-15, the PRC-25 FM radio, an extra battery for it, a sawed-off M-79 grenade launcher, a .22 caliber High Standard Pistol with a silencer, ammunition for all weapons, hand grenades, a gas mask, smoke grenades, a camera and five special bags of dehydrated rice. He quickly realized that he was carrying more than 100 pounds of gear.

While visiting in 2017, reviewing Hardy’s MACV-SOG Vol 10, Doug LeTourneau shows the General John "Jack" Singlaub his photograph in the book from when he was on recon team Virginia. (Photo courtesy of John Stryker Meyer)

His inner thoughts were jarred when the door gunner test fired his 30-caliber machine gun without announcing his intention to anyone. Within a matter of seconds, the Kingbee cut power and began a tight, downward spiral into the LZ, where Childress, the lieutenant, Hoahn and Lap were already waiting. The dizzying downward spiral ended as the pilot revved the engine and landed on the LZ. Cho exited the H-34, with LeTourneau and Cowboy following him into the wood line, connecting with the remaining members of the team. The Kingbee lifted off the LZ and quickly cleared the target area.

And then there was absolute silence.

The audio contrast was startling. As LeTourneau’s senses adjusted to the quiet, he scoped out the LZ, which was in a deep valley between three jungle-covered mountains. Gradually, sounds of the jungle resurfaced, birds chirping, bugs humming. After 10 minutes, Childress signaled LeTourneau to radio Covey with a “Team OK.” The insertion was successful, no enemy activity evident.

Childress moved the team toward the first mountain. Movement was slowed by tall elephant grass and the only communication between team members was hand signals. The team moved in 10-minute intervals, stopping every 10 minutes to listen to what was going on around it. After more than an hour, the team finally emerged from the elephant grass as it continued to climb the first mountain.

LeTourneau was on hyper-alert, his heart pounding hard whether sitting in a long rest period or moving up the mountain. Near the top of the mountain, Lap pointed out an observation platform that had been cut into the jungle high off the ground. From that platform, anyone could observe the LZ and the valley where the team was inserted as well as other open areas that could be used for landing helicopters. Had a trail watcher been sitting on the platform when ST Virginia flew into the LZ? If so, where was he and when would the NVA hit the team?

Late in the day, the team finally reached the top of the mountain and found a wide, well-used trail. LeTourneau’s first thought was, “How could any trail be out here in the middle of nowhere in this thick jungle?”

Regardless, the team set up its night perimeter, far above the trail where it could see anyone moving while remaining camouflaged and out of sight. At last light, Childress made the final commo check with Covey as the team settled in for its first night in the jungle.

It was an uneventful night. Childress did a midnight commo check with Hillsborough, the night command aircraft that flew high above the Ho Chi Minh Trail and the DMZ, and he checked in with Covey in the early morning.

After the team ate breakfast in shifts, Childress directed Lap to move parallel to the trail with Cowboy as the tail gunner in the line of march and LeTourneau walking in front of Cowboy. The team moved slowly in less than 10-minute intervals before taking breaks to listen to the surrounding sounds. They did this because moving next to a trail was fraught with inherent risks.

As ST Virginia moved up the second mountain, Cowboy and LeTourneau began to hear women’s voices off of the trail. Cowboy urged LeTourneau to go explore the sounds. LeTourneau shook his head no, indicating they had to stay with the team. Cowboy, who spoke broken English, repeated the suggestion adding: “It could be a small NVA village. We could kill everyone and make the NVA beaucoup angry. We want to let them know we can hurt them the same way they attack our camps and villages.”

LeTourneau again declined and gave him the hand signal to plant some M-14 Anti-Personnel Mines on the trail behind them, in case NVA soldiers were trailing them. As the team moved on, LeTourneau planted a few more toe poppers and marked their locations on his map after covering them expertly. He laid down some powdered mustard gas on the ground for any tracker dogs that might follow their trail. The mustard gas powder was left over from WWI—how it landed at Phu Bai remained a mystery to LeTourneau. The good news was that it still worked. That fact was confirmed during the next break when the team heard a dog howl in anguish after snorting some of the old mustard gas.

Maybe it didn’t work that well, because a few minutes later, the dog was back on the team’s trail. Cowboy told LeTourneau to use his pistol to kill the dog. LeTourneau’s mind flashed back to Special Forces Training Group where instructors had said the same thing.

LeTourneau pulled out the .22, quietly moved back down the trail, took off his rucksack and moved a few more feet before lying down on the ground, facing the trail. The dog never realized LeTourneau was there. When the dog was about 10 feet away, LeTourneau fired one shot. It struck the dog between the eyes, killing him instantly. The canine dropped in his tracks, out of LeTourneau’s view.

Unaware of what had happened, the dog’s handler moved up the trail. When he got near the dead dog, he stepped on a toe popper. LeTourneau and Cowboy heard the NVA screaming in pain and anguish. They left him behind, figuring he would die shortly.

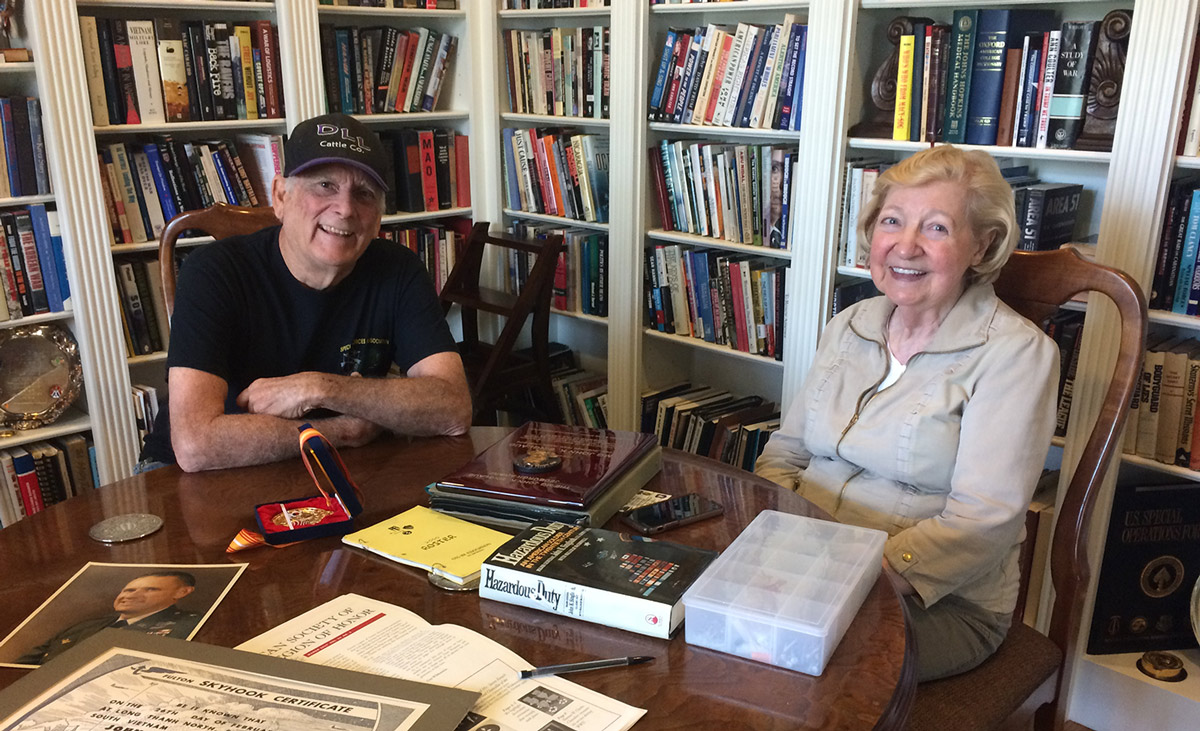

Doug and Joan Singlaub, wife of Major General John K. “Jack” Singlaub, at her home in Franklin TN, in April 2017.

Joan Singlaub passed away recently, on April 27, 2025. A proud American, Joan deeply loved her country and was devoted to honoring those who served. Click here to learn more about this amazing woman. (Photo courtesy of John Stryker Meyer)

The team moved further up the mountain, with LeTourneau and Cowboy providing rear security. Again LeTourneau and Cowboy heard women’s voices below them. Again, Cowboy urged LeTourneau to go downhill and attack the encampment. And again, LeTourneau declined.

By the time LeTourneau completed his last radio call to Covey, the team was enveloped in darkness and team members began to set up a perimeter for the night.

Dawn broke without any enemy activity. When Covey flew over the team in the morning, he warned Childress that a team was being extracted under enemy fire and another was being inserted into a top priority target. “Sit tight,” was the last instruction from Covey. ST Virginia didn’t move from its quiet spot alongside the mountain. During lunch hour, each member ate in shifts and LeTourneau went out to inspect the claymore mines the team had deployed to ensure that the NVA hadn’t turned the deadly explosive devices around to face toward the team. When he completed his inspection, LeTourneau found a log to sit behind.

Later in the afternoon, Childress signaled the team to pull in their claymore mines and prepare to move out. Due to the combined weight of his rucksack and web gear, LeTourneau moved to his knees and slung his rucksack on his back.

Just as it landed on his back, AK-47s opened fire. LeTourneau was slammed to the ground face first. The impact so severe he thought he had broken his nose.

Startled, LeTourneau jumped up with his CAR-15 pointing toward the AK-47 gunfire that was near the front of the team. Surprised that there were no NVA near him, LeTourneau removed the rucksack to discover that four AK-47 rounds had ripped through the 23-pound PRC-25.

He reached into an especially tailored pocket on his fatigue shirt, which was sewn with vertical zippers—one on the left side of the shirt and one on the right side, between the top and bottom pockets on the shirt—pulled out his URC-10 emergency radio and broadcast a general alert for any aircraft in the area. ST Virginia was declaring a Prairie Fire Emergency.

Then, there was sudden, complete silence. Eerily silent.

Amazed at the quietude, LeTourneau walked to Childress, who asked him what he had done with the PRC-25. LeTourneau explained that four rounds had ripped through the radio and that it was probably useless.

“Get the fucking radio,” Childress yelled. “What if it’s working and we leave it behind for those assholes to use?”

Stunned, LeTourneau went back, picked up the ruck sack and walked back to Childress, who grabbed the handset as NVA troops began firing at ST Virginia, and yelled into the radio, “We have a fucking Prairie Fire Emergency. Get us the fuck outta here or I promise you I’ll kick your ass all the way back to Saigon.”

As the firefight raged on, the remainder of the team was lying down on the ground, firing at the NVA, while Childress and LeTourneau continued to argue while standing up, oblivious to the AK-47 rounds cracking over their heads.

LeTourneau yelled back at Childress, “It don’t work!” while pointing at the PRC-25 radio where the antenna had been shot off. No antenna, no commo.

LeTourneau grabbed a spare whip antenna and handed it to Childress, who screwed it into the PRC-25.

This time, Childress screamed into the radio, “We need an exfil, now! I’m declaring a Prairie Fire Emergency. Is anyone out there?”

Within a second or two there was a response: “Calm down, Childress. I realize you’re under fire,” said a Covey rider. Just at that moment several AK-47s opened fire from the wood line near the log where LeTourneau had been unceremoniously slammed onto his face. Lap and Cowboy returned fire.

Covey rider continued: “We heard your team declare a Prairie Fire Emergency on the Guard frequency and I’ve rallied the cavalry. What’s your mark? Do you have an LZ in sight?”

Before Childress said a word into the radio, he turned to LeTourneau and said, “See. It works. Suppose we had left it for the NVA. Never. I say again, never, ever leave behind a radio.”

As if to emphasize that point, the NVA opened fire again as Lap began looking for an LZ while he moving the team down the hill, away from the most concentrated NVA gunfire.

Cutting LeTourneau no slack, Childress roared, “Tell Covey we’ll give him a fix in five minutes. We’ll probably need strings to get out of here. I doubt we can make it down to the valley where a Kingbee can pick us up.”

Without missing a beat, LeTourneau—who for the first time felt four burning stings in his back—repeated those words to Covey while he and Cowboy began providing covering fire as the tail element of the team. Then LeTourneau nodded to Cowboy, who ignited several claymore mines that the team had set out on its perimeter. Those mines only slowed the NVA for a few seconds.

Before the dust and debris from the blasts had settled, NVA soldiers were moving through it toward Cowboy and LeTourneau.

Without saying a word, the two men took turns firing at the enemy while moving down hill. Rotating around each other. Cowboy would fire several bursts from his CAR-15, and then reload. As he reloaded, LeTourneau would open fire, providing covering fire for the team.

During one short lull, Cowboy again planted a claymore mine in the direction of the advancing NVA and LeTourneau dug out another claymore from his ruck sack and placed a 10-second delayed fuse in it. When the NVA again advanced, Cowboy ignited his claymore mine. When the NVA moved toward the team again, LeTourneau ignited his fuse and ran down the hill with Cowboy to catch up to their team.

Before they reached the team, two B-40 anti-personnel rockets slammed into the trees above them, showering them with shrapnel. A few more exploded as LeTourneau and Cowboy moved down the hill. Then the 10-second fuse ignited another claymore. It bought precious time for the gun-and-run team of LeTourneau and Cowboy to cover ground and catch up to the remainder of ST Virginia.

As Childress called in air strikes, LeTourneau reflected on how surreal this firefight had been. It wasn’t anything like he had witnessed on television or in any movie. Instead of men charging each other and killing each other in plain sight, here in triple-canopy jungle, he observed green tracers from AK-47s first, or at the most an enemy hand or foot. And, somehow the NVA found firing lanes where they could launch shoulder-held B-40 anti-personnel rockets that slammed above and around them as they raced down the hill for their lives. Again, the voices of his Special Forces instructors echoed in his mind: they had told the young aspiring Green Berets at Ft. Bragg that the NVA was a tough, resilient opponent. Many had fought against the Japanese during WWII and against the French, driving them from Vietnam in 1954 after the battle of Dien Bien Phu in North Vietnam.

The sounds of Kingbees in the distance and the crashing thunder of B-40 rockets slamming into the trees above his head shook LeTourneau out of his moment of introspection and turned his undivided attention to a crescendo of AK-47 fire from the enemy. ST Virginia responded with volley after volley of full and semi-automatic gunfire while LeTourneau and Cho fired several M-79 rounds toward the densest section of jungle where the AK-47 gunfire was emanating.

Through the gunfire, someone popped a smoke grenade, which brought the Kingbees closer to the RT Virginia’s location in the jungle. Over the din of gunfire, Childress and Cowboy told everyone to put on their Swiss seats and to prepare for a string extraction.

In short order, a Kingbee was hovering over ST Virginia, more than 125 feet above the jungle floor. LeTourneau, Cowboy, Cho and Hoanh hooked their D rings into the old McGuire rig that hung from the end of the ropes and shortly were being lifted out of the jungle.

As the quartet of recon men was being lifted into the air, the NVA unleashed another salvo of AK-47 gunfire and several B-40 rockets. Shrapnel from the rockets hit them with varying degrees of size and velocity. All of them were wounded.

It was during those explosions that LeTourneau realized his CAR-15 had somehow become caught in the rope above him, just far enough away that he couldn’t reach it. He pulled out his M-79 and launched a 40 mm grenade toward the NVA positions: now, all he could see of the enemy were hundreds of muzzle blasts from AK-47s and green tracers rounds eerily climbing upward toward the quartet of ST Virginia men.

John Meyer, left, and Doug LeTourneau, at right, on 11/11/11, the day he received the Purple Heart for wounds he received in November 1968 on his first SOG reconnaissance mission across the fence in Laos with Spike Team Virginia out of FOB 1, Phu Bai. (Photo courtesy John Stryker Meyer)

Before he could reload his M-79, the Kingbee began to move away from the target area, surprising him because the men had not cleared the jungle yet. Instead of continuing to climb out of the target, moving straight up until the men cleared the jungle’s triple canopy of trees and vegetation, the Kingbee was moving away from the target area due to the heavy enemy ground fire. In recent months at least two Kingbees were shot down during string extractions from hot targets, but these facts were unknown to LeTourneau at that time.

Shrapnel from the B-40 rockets exploded around the ST Virginia men stinging them with pieces of hot metal, further spooking the Kingbee crew. LeTourneau began to violently collide with the tall jungle trees. Feeling like a metal ball in a pinball machine, LeTourneau caromed off several more trees as at least one more B-40 exploded in the treetops, again showering him with shrapnel.

A tree branch hit LeTourneau from the side and turned him upside down in his rope Swiss seat. As the rope seat began to slip down from his hips, LeTourneau remembered Spider telling how a One-Zero from another team had been recently shot out of his Swiss seat during a rope extraction.

Another tree struck LeTourneau before he was able to muster a surge of strength and momentum to reach up and grab the rope above him as his body finally cleared the treetops.

The only thing between him and certain death below on the jungle floor 200 feet below was the single piece of rope tied into the Kingbee.

With one final urgent pull, LeTourneau was able to move himself upright in the Swiss seat as the Kingbee continued to climb higher into the sky, distancing itself from the fury of the exploding B-40s and AK-47 gunfire while gaining air speed.

As the Kingbee ascended, the heavily sweating LeTourneau clung to the rope as another sensation overwhelmed his body: chattering teeth. Within a matter of minutes, the Kingbee had climbed to an altitude of more than 5000 feet, where the air is thinner and much, much colder than on the jungle floor—so much colder that LeTourneau’s body began shaking violently from the dipping temperatures as the Kingbee continued to climb into the safety of higher altitude.

LeTourneau would never forget that extraction. Rockets were exploding around him while he was dripping with sweat, hanging upside down, and in the next moment, he felt as though his sweat was freezing to his body.

Few people realize just how cold and terrifying it is to be hanging from a rope, freezing to death while going more than 100 miles per hour dangling under a chopper.

In ordinary circumstances, few people would ever think about freezing to death over Southeast Asia, but for the men in C&C, it was just another hurdle they had to clear.

As the Kingbee headed east, LeTourneau looked down on spots in the jungle that appeared to be good LZs, thinking “Why don’t you land there?”

But, ST Virginia’s collective agony continued until the Kingbees finally landed in South Vietnam. By that time, every member of ST Virginia had their circulation cut off to their legs. They couldn’t stand or walk. All they could do was unhook from their Swiss seat, grab their stuff and try to get the circulation going again in their legs while the door gunner helped them get back to the Kingbee.

When the team returned to the Quang Tri launch site before heading south to Phu Bai, Childress pulled LeTourneau aside and told him, “Take good care of that radio. You’re going to take it on the next mission whether you like it or not.” Childress and the lieutenant returned to the S-3 tent, while LeTourneau went into the old WWII tent where the Vietnamese members sat on old stiff cots, searching each other for shrapnel wounds while bandaging the more serious wounds.

As darkness fell, the Kingbees lifted off from Quang Tri for Phu Bai. When the old war birds landed on the FOB 1 landing zone, ST Virginia was greeted by one man: Former ST Virginia One-Zero John McGovern. He greeted each of the team members as they exited the Kingbees, asking each one, “Are you okay?”

After the Kingbees departed, bathing them in the sand, dust and LZ debris kicked up by the prop wash, McGovern asked Childress, “Did you hear about Bader, et al?”

Childress shook his head. “No, what happened?”

“November thirtieth, we lost a Kingbee with seven SF troops on it and we lost the entire Kingbee crew. They were a bunch of straphangers who volunteered to pull an Elder Son mission on the trail. But, an anti-aircraft round hit the Kingbee en route to the target. It exploded in mid-air. They never had a chance.”

In silence, McGovern drove the tired, dirty and hungry team back to the team room. As the Vietnamese team members climbed off the truck, McGovern turned to LeTourneau and said, “You know what was really scary about that mission? The day before they got shot down, me, Lynne Black, Rick Howard, John Peters, Tim Schaff and a few others had volunteered and were actually on the Kingbee suited up ready to go, only to be canceled the last minute due to bad Whiskey X-Ray (weather) in the A.O. That was too close for comfort.”

After a long pause he asked LeTourneau, “How did it go out there? I heard you were good on the radio. You didn’t get rattled. You ain’t a cherry no more. You’ve joined a small, unique club of SF men, C&C recon men who went across the fence.”

“It was nothing like I could have ever imagined,” LeTourneau responded. Looking toward the Vietnamese team members, he added, “Let me get some chow for the indig. You were right about them. They have ice in their veins. I’m beat. I’ll see you in the morning.”

LeTourneau walked through the white sand to the mess hall, picked up some fresh sandwiches and cold sodas for the team. After lingering with the Vietnamese team members LeTourneau returned to his room, finally taking off his rucksack and web gear.

As he started to undress, LeTourneau became aware of pain in his back, from where the four AK-47 rounds had slammed him face-first into the ground. First he peeled off his jungle fatigue shirt and was amazed to find four bullet holes in it. Then, he took off his undershirt. Ditto! Four bullet holes were in it. LeTourneau picked up the rucksack: four bullet holes were in it—both in the front and the back—something he hadn’t realized during the firefight.

Then, he looked in the mirror and saw the four large welts and broken skin up his spine where the AK-47 rounds had hit his body after punching through his rucksack and PRC-25.

Only then did LeTourneau begin to comprehend just how lucky he had been hours earlier in the day when the NVA shot him in the back four times.

LeTourneau began to cut away the black electrical tape around his socks, which he pulled up and over his pant legs to keep out leeches and bugs. Then he made a startling discovery:

When he pulled his pant leg from the sock and pulled off his right boot, four AK-47 bullets fell on the ground. In the heat of battle, the Frenchman didn’t realize that after he was shot in the back, the four 7.62 mm NVA rounds had fallen down through his pants and socks into his right boot.

He stood in utter amazement, staring at the four rounds on the floor, before picking them up and throwing them in the sand outside his room.

Exhausted, LeTourneau walked over to the shower room. The water stung the wounds in his back. Amazingly, the four bullets had enough energy to penetrate his skin wounding him, but not enough to get under his skin.

Too tired to treat the four bullet wounds in his back and the shrapnel wounds in his arms, LeTourneau finished his shower and went to bed.

The PRC-25 wasn’t called a “Prick-25” for nothing. In addition to weighing a ton, they were famous for their inconsistency in the field. The Frenchman would use this same radio on Christmas Day to help ST Idaho avoid an NVA ambush.

Editor’s note: Doug “The Frenchman” Le Tourneau, 72, passed away unexpectedly on 26 July 2019. Just weeks before, on July 9, LeTourneau was featured in a two-hour Jocko Podcast, which was posted by Jocko Willink, on July 17. Click here to hear to that memorable podcast.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR — John Stryker Meyer entered the Army Dec. 1, 1966. He completed basic training at Ft. Dix, New Jersey, advanced infantry training at Ft. Gordon, Georgia, jump school at Ft. Benning, Georgia, and graduated from the Special Forces Qualification Course in Dec. 1967.

He arrived at FOB 1 Phu Bai in May 1968, where he joined Spike Team Idaho, which transferred to Command & Control North, CCN in Da Nang, January 1969. He remained on ST Idaho to the end of his tour of duty in late April, returned to the U.S. and was assigned to E Company in the 10th Special Forces Group at Ft. Devens, Massachusetts, until October 1969, when he rejoined RT Idaho at CCN. That tour of duty ended suddenly in April 1970.

He returned to the states, completed his college education at Trenton State College, where he was editor of The Signal school newspaper for two years. In 2021 Meyer and his wife of 26 years, Anna, moved to Tennessee, where he is working on his fourth book on the secret war, continuing to do SOG podcasts working with battle-hardened combat veteran Navy SEAL and master podcaster Jocko Willink.

Visit John’s excellent website sogchronicles.com. His website contains information about all of his books. You can also find all of his SOGCast podcasts and other podcast interviews. In addition, the website includes in stories of MACV-SOG Medal of Honor recipients, MIAs and a collection of videos.

Leave A Comment